Changing earnings requirements for Unemployment Insurance could improve access and better support U.S. workers

Temporary changes to the Unemployment Insurance program played an enormous role in the U.S. policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting sharp-but-short recession in 2020. Typically, Unemployment Insurance replaces some portion of beneficiaries’ wages (up to a certain amount) for a period of time when they lose their jobs through no fault of their own, with the amount of benefits and their duration varying state by state. Yet amid the public health emergency and economic uncertainty in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, UI generosity and eligibility expanded in unprecedented ways to protect workers’ health—and pocketbooks—with impacts that could help inform changes to the program and its eligibility rules.

Pandemic conditions were extraordinary in many ways, and the UI system’s response reflected the need for urgent and sweeping action. The federal government initially provided a $600 per week supplement, on top of regular benefits, to all UI recipients. It also created the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program to provide benefits (including the $600 supplement) to workers who are typically not eligible for Unemployment Insurance, such as self-employed workers. Early in the pandemic, lawmakers also temporarily modified rules requiring that UI beneficiaries actively search for work in light of the potentially adverse public health consequences that maintaining that requirement could have had.

As a result of all of these changes, far more people received UI benefits than would have received them under more normal circumstances, including many workers who had more than 100 percent of their weekly earnings replaced by Unemployment Insurance. These changes meant many workers who lost their jobs amid the pandemic recession were able to stay afloat, stabilizing local economies across the United States and helping to prevent a longer, more painful recession. This pandemic experience stands in stark contrast with how Unemployment Insurance typically serves workers, including during other times of economic crisis.

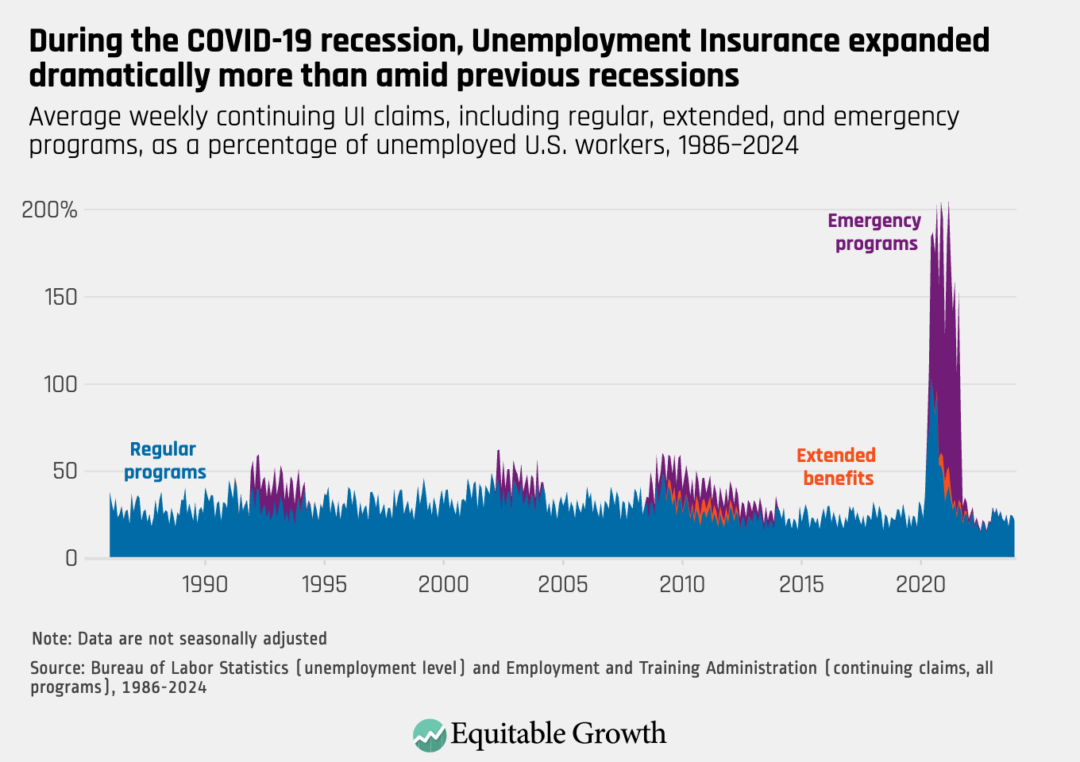

During times of economic expansion, the number of U.S. workers on Unemployment Insurance is fairly small, with about one-third or less of all people who are unemployed. During and immediately after the recessions that began in 1990, 2001, and 2007, during which the federal government created programs to extend the duration of UI benefits beyond the regular coverage period, the number of U.S. workers on Unemployment Insurance was larger. In each of those recessions, the number of UI claimants was about 60 percent of the number of unemployed workers at its highest point.

During the COVID-19 recession, however, the UI system expanded much more dramatically than it had amid previous recessions, as discussed above. The resulting effects on the number of U.S. unemployed workers applying for and receiving benefits were significant, compared to the three previous recessions in recent U.S. history. In some months, the average number of weekly continuing UI claims, an approximation of the number of people receiving UI benefits,1 significantly exceeded the total number of unemployed workers, surpassing 200 percent of workers at a few points in 2020 and 2021. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

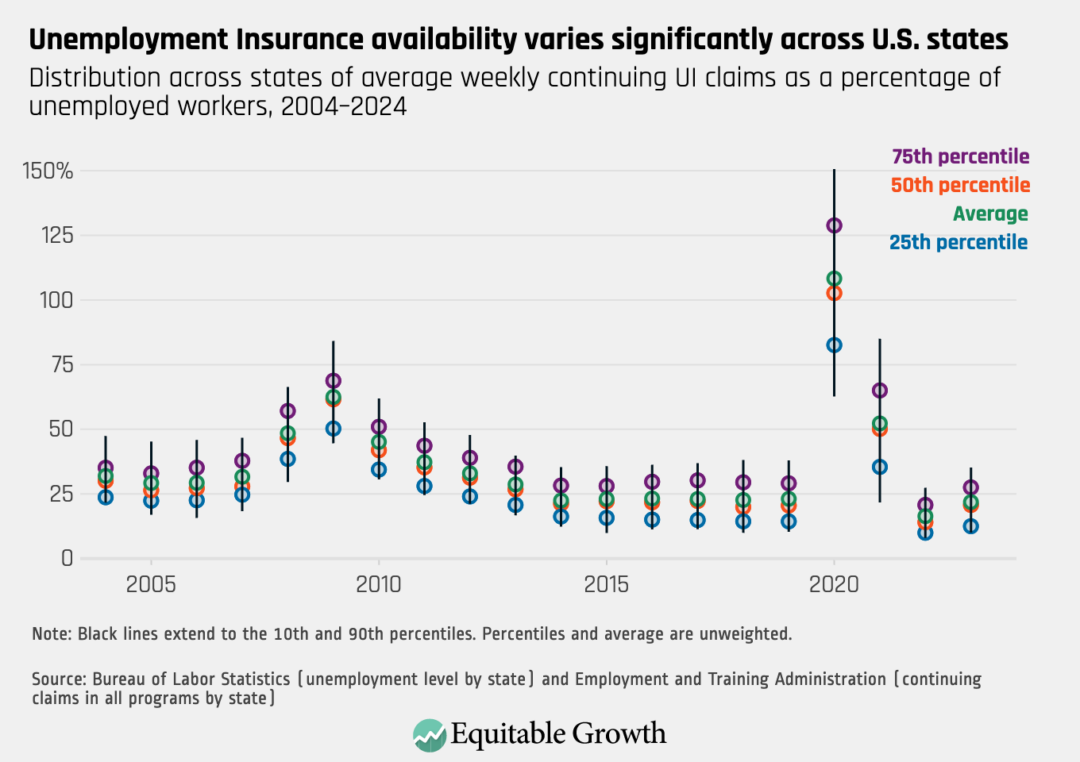

Federal emergency programs create variations in the degree to which the UI system serves unemployed U.S. workers over time. But there also are variations among the states in the share of unemployed workers who receive Unemployment Insurance, even under normal economic conditions. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

As Figure 2 shows, UI availability in the median state (depicted by the orange circles) fairly closely tracks average availability across the country, but there is otherwise substantial variation. In 2019, for example, when the labor market was fairly strong and UI claims stood at roughly 25 percent of unemployed workers nationwide, UI availability in the 90th percentile state—Rhode Island—was 38 percent, while it was 11 percent in the 10th percentile state of Georgia. At the furthest extremes, weekly continuing UI claims in 2019 corresponded to only 6 percent of unemployed workers in the state where that share was the lowest (North Carolina) and 52 percent of unemployed workers in the state where that share was the highest (New Jersey).

Diving deeper into the data, it becomes clear that across years, as macroeconomic conditions change, the same handful of states tend to have consistently high UI availability, while another group of states tends to have consistently low UI availability. This suggests that persistent policy differences regarding UI eligibility and access, rather than changes in economic conditions or population characteristics, are responsible for the gap between the states with the highest and lowest UI availability.

Perhaps the most significant UI eligibility rules in terms of barriers to access are those that deal with how much workers need to have earned (and when) in order to claim Unemployment Insurance when they are laid off. With very few exceptions, U.S. workers are required to earn somewhere between several hundred and several thousand dollars before becoming eligible for UI benefits. Typically, states also either implicitly or explicitly require that those earnings be spread out over at least two quarters.

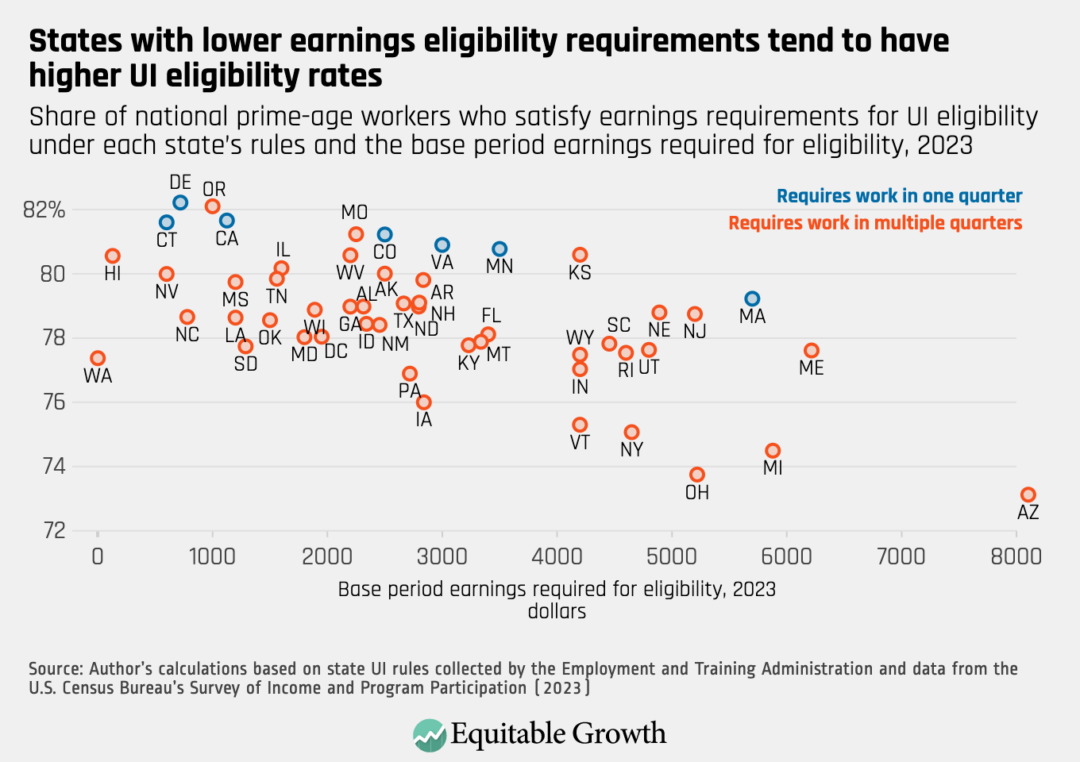

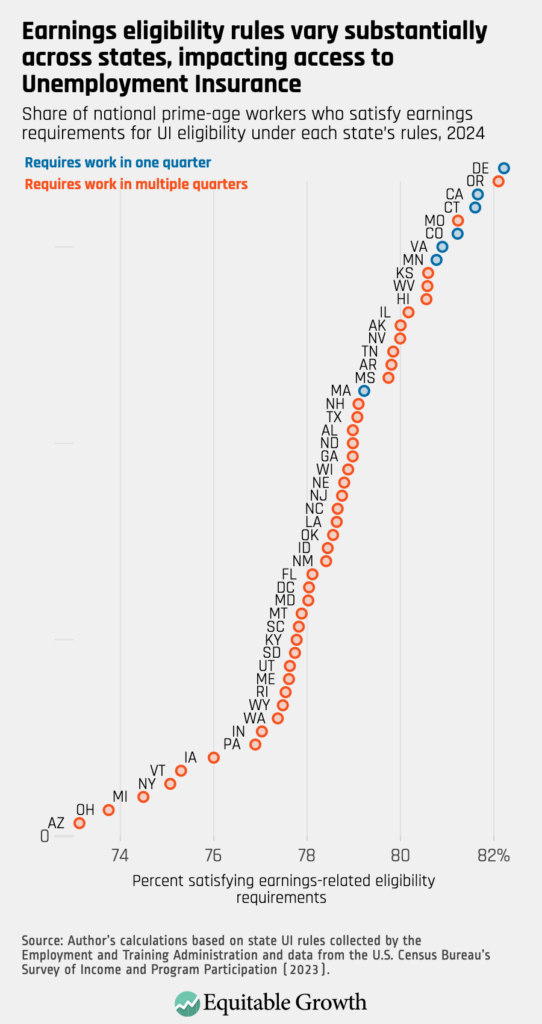

These earnings-related eligibility rules have important consequences for workers’ access to Unemployment Insurance and UI availability in each state. As seen in Figures 3 and 4 below, states that have less stringent restrictions on earnings tend to have broader access to Unemployment Insurance. In order to focus on differences in policy across states rather than local economic conditions or population characteristics, the estimates in Figures 3 and 4 were calculated by applying 2024 UI earnings eligibility rules in each state to 2023 earnings for a national sample of so-called prime-age workers (those between the ages of 25 and 54, who tend to have stronger connections to the labor market).

These differences in access to Unemployment Insurance not only affect workers’ ability to stay afloat in times of hardship but also can have impacts on local economies in economic downturns. As one might expect, states that require workers to earn more before becoming eligible for Unemployment Insurance tend to see fewer workers meet those requirements. The magnitude of this relationship is economically meaningful. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Consider Delaware and Arizona, the states with the highest and lowest earnings eligibility rates, respectively. In 2023, Arizona required workers to earn more than $8,100 to become eligible for UI benefits, while Delaware required them to earn only about $700. That difference could account for about 5.3 percentage points of the 9.1 percentage point gap between those two states’ UI eligibility rates.

Figure 3 also illustrates the importance of requirements related to when the income is earned. The seven states that do not require earnings over multiple quarters, seen in blue, tend to have higher eligibility rates than other states that require similar amounts of earnings to be accrued over two or more quarters. Six of these seven states are among the eight states with the highest UI eligibility rates, and the seventh, Massachusetts, has an above-average eligibility rate.

These varying earnings rules make eligibility for Unemployment Insurance vastly unequal based on where workers live. Figure 4 depicts this geographic inequality, showing the estimated share of U.S. prime-age workers who would meet earnings eligibility requirements under each state’s rules. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

Again comparing the most and least restrictive states, in Arizona (the most restrictive state) slightly more than 73 percent of U.S. prime-age workers would satisfy the state’s earnings eligibility requirements, while in Delaware (the most inclusive state) more than 82 percent of workers would qualify.

Conclusion

As we saw with the UI expansions that occurred amid the COVID-19 pandemic and other recent recessions, broader UI coverage can help unemployed workers weather the time it takes to find jobs that better match their skills and align with their career goals. While increasing UI coverage to levels seen under federal emergency programs would require substantial changes to a variety of eligibility rules, there is room for changes to state-level earnings requirements specifically.

Unemployment insurance reform: a primer

October 31, 2016

Even though a number of other preconditions contribute to determining which workers are ultimately eligible for Unemployment Insurance, the most stringent earnings requirements exclude nearly 1 in 10 prime-age U.S. workers from the UI system, relative to the most inclusive requirements. Adjusting down the required earnings level and removing the requirement for these earnings to be made over multiple quarters would expand access to Unemployment Insurance, improving worker well-being in times of hardship.

Indeed, progress can be made without doing anything more dramatic than more broadly adopting rules that are already in place in some states. These changes would meaningfully enhance the degree to which this essential program serves unemployed workers.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!

End Notes

1. Comparing continuing claims to unemployed workers is imperfect, since not all unemployed people are eligible for Unemployment Insurance. Additionally, not all people receiving unemployment benefits are unemployed. That’s because, in some cases, and during the pandemic in particular, the timing of claims may not align closely with the timing of the underlying spell of unemployment. However, using continuing claims as a proxy does illustrate the degree to which the pandemic response differed from usual UI practice and highlights the degree to which unemployed workers could potentially benefit from an expanded UI system.