Paid sick leave means dads can spend more time caring for loved ones and less time worrying about missing work

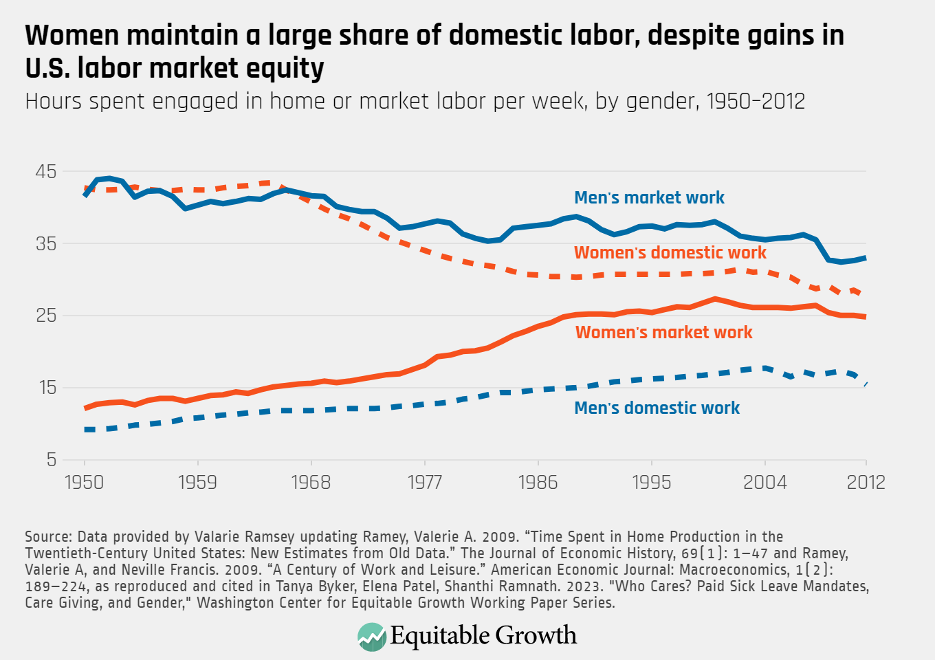

The economic story of the United States in the post-WWII era is arguably the dramatic surge in women’s labor force participation. The increases in hours worked and income generated by women over this period has been pivotal for U.S. economic growth, compensating for the stagnation or only modest gains in men’s income over the same time, especially since the 1970s. Despite these growing professional responsibilities, women continue to shoulder the lion’s share of domestic duties, including child-rearing, caring for loved ones, and homemaking. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

This gendered distribution of household labor, especially in the context of care, contributes both to the recent stagnation in women’s U.S. labor force participation and the persistent gender wage gap, making it a recurring impediment to broadly shared economic growth. Some scholars and policymakers point to family-friendly policies, such as paid family and medical leave and affordable child care, as potential tools for fostering gender equity in the home and at work. These provisions equip workers with the time and financial resources necessary to better balance their work and family responsibilities.

Paid sick leave—a workplace benefit offering short-term job protection and wage replacement for workers who are sick or caring for a sick loved one—is one such family-friendly policy that results in a more equitable division of labor at home and at work, according to a recent working paper by Tanya Byker of Middlebury College, Elena Patel of the University of Utah, and Shanthi Ramnath of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

Importantly, the gendered division of caregiving at home does not necessarily reflect a lack of interest, desire, or expectation on the part of men. While social expectations and gender norms do play into deciding who cares for whom, families also consider other economic factors.

Given the enduring gender wage gap, it may be, on average, more expensive for men than women to take unpaid leave for caregiving purposes. For instance, if the average father earns $1,000 a week and the average mother earns $860 in paid labor—assuming a heterosexual, two-parent household—families will face fewer economic consequences, or opportunity costs, if the mother temporarily halts work to address sporadic or short-term caregiving responsibilities, such as when a child is home sick with a cold or the flu.

These financial considerations create a self-reinforcing cycle where the gender wage gap leads to more caregiving responsibilities for women, and these duties in turn help to maintain the wage gap. Gender-neutral policies that offer wage replacement during times of illness or caregiving, such as paid sick leave or paid family and medical leave, can interrupt this cycle by reducing the opportunity costs for workers who need to step away momentarily from paid work to provide care for a loved one.

Overall 77 percent of U.S. private sector workers have access to paid sick leave, making it a relatively common workplace benefit. But access is not equitable across the economy. Ninety-four percent of workers with wages in the top quartile can take paid sick leave, compared with just 55 percent of workers with wages in the bottom quartile. Likewise, only 51 percent of part-time, private-sector workers have sick leave benefits. To expand coverage, 13 states and the District of Columbia have adopted sick leave ordinances—a legal right for covered workers to accrue sick time on a per-hours-worked basis.

To investigate how these ordinances are influencing workers’ leave-taking behavior, Byker, Patel, and Ramnath used the 2006–2019 basic monthly files of the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey. The co-authors compared respondents’ reported absences from work due to sickness or care-giving issues and implemented a two-stage, difference-in-differences model to compare reasons for work absences before and after the implementation of sick leave ordinances, as well as across states without similar laws.

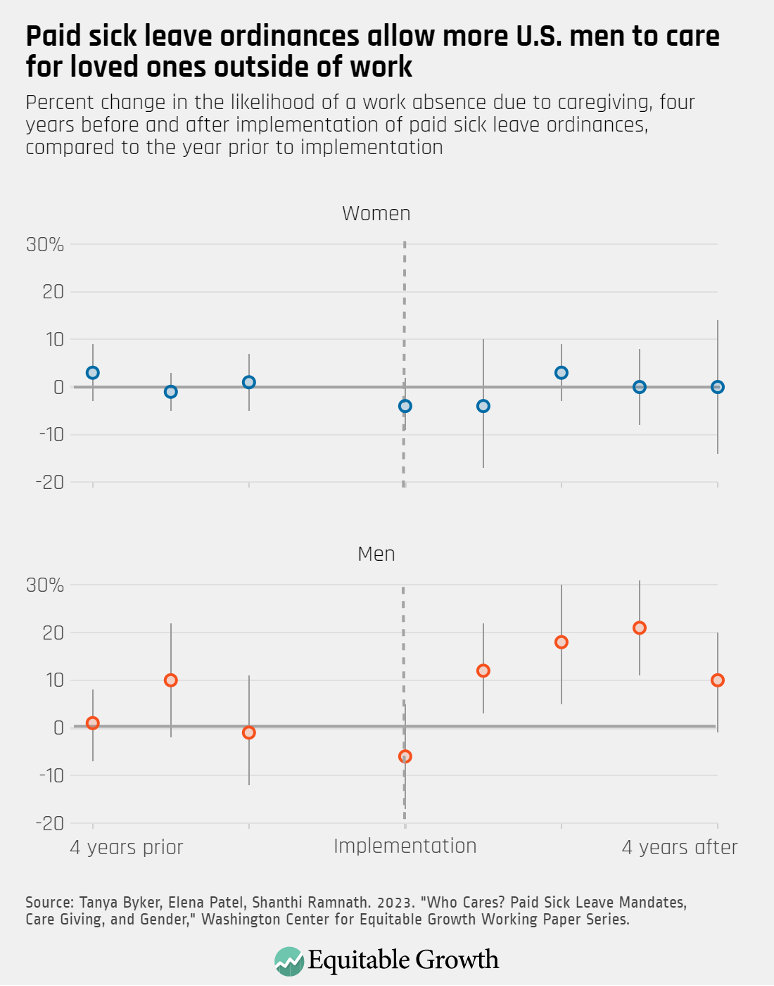

The researchers find that, overall, paid sick leave policies do not significantly increase the likelihood of workers taking leave due to their own illnesses or caregiving duties. These overall findings, however, concealed significant variations by gender, parenthood status, and prior access to leave. Specifically, paid leave ordinances increased the likelihood of men taking leave specifically for caregiving by 10 percent to 20 percent, with the results being primarily driven by men with children in their households.

The increases in caregiving were most notable among men who historically have less access to employer-sponsored sick leave, primarily Hispanic men and those without a bachelor’s degree. Absences for men’s personal illnesses remained unchanged, and no such impact was identified for women, irrespective of whether they had children in the household. Since women were predominantly providing care at home prior to such policies, expanding access to paid sick leave may have facilitated men’s efforts to reach the level of care typically provided by women. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

In addition to their implications for gender equity, these findings also underscore how paid sick leave ordinances can serve as an effective, low-risk means of extending access to sick time. The fact that leave-taking behavior remained generally unchanged following the implementation of these ordinances should alleviate employers’ concerns that such policies will result in a significant increase in absences or workers’ misuse of the new benefits.

In fact, only workers with a discernible need for such benefits—mainly Hispanic and less-educated fathers with children at home—altered their work schedules. This aligns with previous research suggesting that sick leave ordinances pose a generally low cost to employers and are most effective when they include employers less likely to provide this benefit otherwise.

There is, of course, no silver bullet for achieving gender equity both at home and in the workplace. Social norms, expectations, and persistent gender-based discrimination continually influence the personal and professional lives of men and women, often in ways that go unseen. This recent research by Byker, Patel, and Ramnath, however, demonstrates how gender-neutral policies can impact the financial decisions families make around caregiving, potentially leading to more equitable divisions of labor.

By enabling fathers to contribute more to home care without sacrificing their wages, paid sick leave plays a vital role in helping men and women balance their personal and professional responsibilities. This balance, in turn, may help shrink the gender wage gap, ultimately paving the way for widespread and more sustainable U.S. economic growth.