Pre-pandemic vulnerabilities, the Paycheck Protection Program, and planning for future crises

Fast facts

- The COVID-19 pandemic that began in early 2020 hammered small businesses in the United States, with its effects felt disproportionately among the most vulnerable small business owners, especially those from historically disadvantaged racial and ethnic groups.

- By April 2020, toward the end of the short-but-sharp COVID-19 recession of 2020, the consequences for these small businesses were devastating. Active business ownership declined by 41 percent for Black small business owners, 32 percent for Latino small business owners, and 26 percent for Asian American small business owners, compared to a 17 percent decline for White small business owners.1

- Amid this crisis, U.S. policymakers implemented the largest public policy intervention for small business owners, the Paycheck Protection Program, which provided financial support to struggling small businesses across the country through several successive tranches of government loans that could be converted into grants.

- This report examines how more than $800 billion in funding under the Paycheck Protection Program was delivered through financial institutions that continually underserve business owners of color to understand whether the funding was distributed less equitably than the U.S. Congress intended.

- The available preliminary studies on the Paycheck Protection Program are informative, but more work is needed to fully understand the behavioral and structural forces that caused these small business owners of color to be immediately more vulnerable to the pandemic and the resulting recession, which left them less capable of recovering fully amid the ensuing U.S. economic recovery that began around the middle of 2020—despite the promise of the Paycheck Protection Program.

- Preliminary policy recommendations are that federal policymakers should already prepare for the next crisis now by correcting the institutional biases in the U.S. financial system that continue to lead to racial and ethnic disparities in lending to small business owners of color and consider providing relief directly to these business owners rather than having private financial institutions act as intermediaries, as they did in the Paycheck Protection Program.

Overview

The COVID-19 pandemic that began in early 2020 hammered small businesses across the globe. The number of active businesses declined precipitously, supply chain interruptions reduced business operations, and global trade declined substantially.2 In the United States, the pandemic’s effects were felt disproportionately among the most vulnerable small business owners, especially those from historically disadvantaged racial and ethnic groups.

By April 2020, toward the end of the short-but-sharp COVID-19 recession of 2020, the consequences for these small businesses were devastating. Active business ownership declined by 41 percent for Black small business owners, 32 percent for Latino small business owners, and 26 percent for Asian American small business owners, compared to a 17 percent decline for White small business owners.3

Amid this crisis, U.S. policymakers implemented programs to help small businesses weather the pandemic and resulting recession through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act. The largest public policy intervention for small business owners in the CARES Act was the Paycheck Protection Program, which provided financial support to struggling small businesses across the country through several successive tranches of government loans that could be converted into grants.

The CARES Act stated specifically that the program’s administrators at the U.S. Small Business Administration were to focus on small business owners of color, among other disadvantaged business owners. Specifically, the new law stipulated:

[I]ssue guidance to lenders and agents to ensure that the processing and disbursement of covered loans prioritizes small business concerns and entities in underserved and rural markets, including veterans and members of the military community, small business concerns owned and controlled by socially and economically disadvantaged individuals (as defined in section 8(d)(3)(C)), women, and businesses in operation for less than 2 years.4

In this report, I look specifically at those small business owners of color, as defined under the CARES Act, to examine how funding under the Paycheck Protection Program was delivered through financial institutions that continually underserve business owners of color. The purpose is to understand whether the program’s more than $800 billion in total funding was distributed less equitably than the U.S. Congress intended.5

I first summarize the body of research to date on lending to these historically disadvantaged U.S. small business owners of color prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. I then review studies that examine the pandemic’s differential impacts on these small business owners of color, compared to other small business owners. The available preliminary studies on the Paycheck Protection Program are informative, but more work is needed to fully understand the behavioral and structural forces that caused these small business owners of color to be immediately more vulnerable to the pandemic and the resulting recession, which left them less capable of recovering fully amid the ensuing U.S. economic recovery that began around the middle of 2020—despite the promise of the Paycheck Protection Program.

I then offer some preliminary policy recommendations based on this review of this research. Briefly, I suggest that federal policymakers should already prepare for the next crisis now by correcting the institutional biases in the U.S. financial system that continue to lead to racial and ethnic disparities in lending to small business owners of color and consider providing relief directly to these business owners rather than having private financial institutions act as intermediaries, as they did in the Paycheck Protection Program.

I close this report by highlighting unanswered questions for which further research is needed that could help expand our understanding of this continued disparity in lending to small business owners of color. I also examine the dearth of data for this research, which hinders the development of new and more rigorous research.

Racial and ethnic inequality in U.S. small business lending outcomes during and before the COVID-19 pandemic

During the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was very little information available on the financial health of small businesses owned by people of color in the United States. There are very few high-frequency, nationally representative data sources on U.S. small businesses. The data sources that do exist, such as the U.S. Census Bureau’s Business Formation Statistics data or its temporary Small Business Pulse Survey, either do not collect or do not report data disaggregated by the race or ethnicity of the business owner. These data reported only the number of new business applications filed and, for existing businesses, information on changes in revenue, employment, and expectations during the pandemic.

Much of what we did know early on came from work by the economist Robert Fairlie at the University of California, Santa Cruz and the National Bureau of Economic Research.6 Fairlie used data released monthly from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey to measure changes to the number of small business owners at several time intervals between January 2020 and June 2020. During this time the CARES Act, which included the Paycheck Protection Program, was under consideration in the U.S. Congress. After it was passed on March 27, 2020 the first tranche of $349 billion in federal funds to small businesses was disbursed followed by a second round of funding which was allocated by Congress on April 24 of that same year.

The Current Population Survey is one of the few datasets that provide detailed demographic information on individuals within the United States in a timely manner—though, importantly, it does not include data on business performance. The CPS data are released one month after the survey date and include information on which individuals own a business as their main job. The data also report the race and ethnicity of the survey respondents, which allowed Fairlie to examine whether there were steeper declines in business ownership activity among people of color.

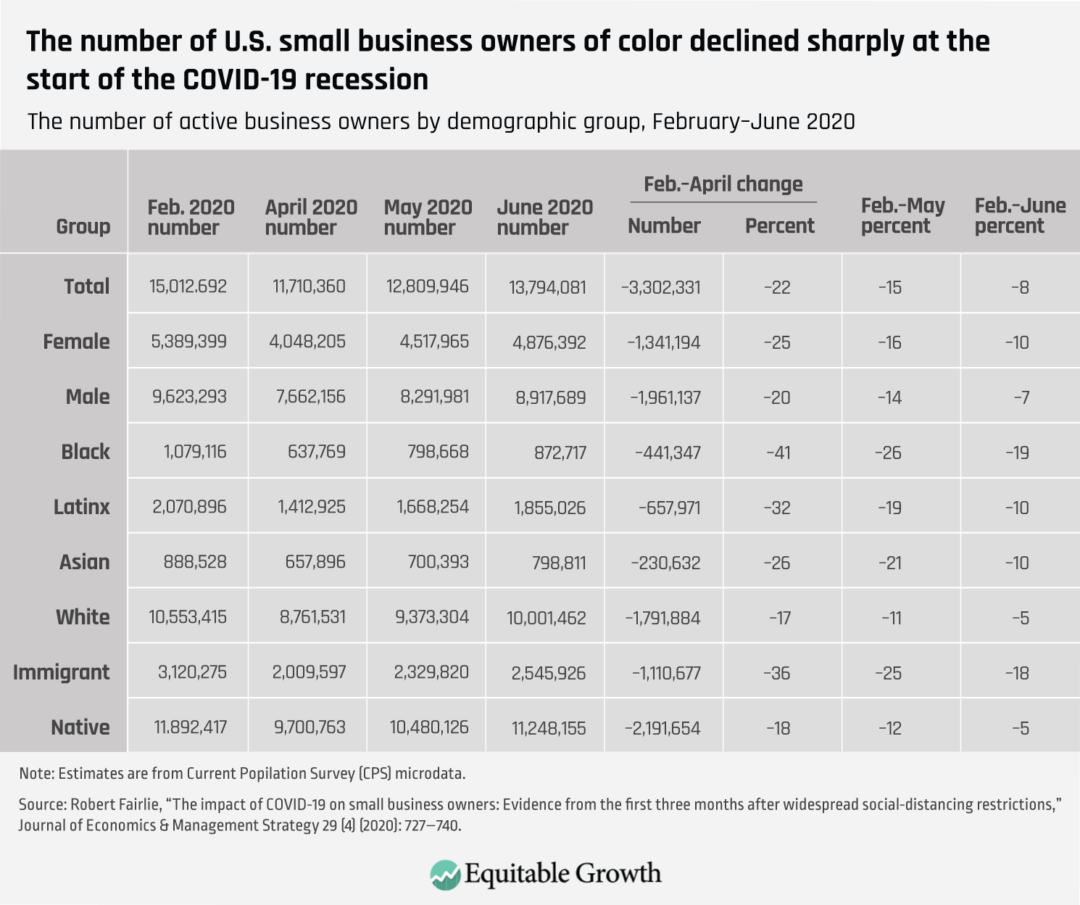

Fairlie’s research, published in August 2020, confirms what many suspected. Business ownership activity fell across the board but at a steeper rate among people from disadvantaged racial and ethnic groups during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. From February 2020 to April 2020, the number of Black small business owners fell most dramatically, by 41 percent. Latino small business owners and Asian American small business owners declined by 32 percent and 26 percent, respectively. In contrast, the number of White small business owners fell by 17 percent.7

Fairlie finds that the number of Native American business owners also declined by 18 percent, while small business owners who identified themselves as immigrants across all racial and ethnic groups in the Current Population Survey fell by 36 percent. His work provides clear evidence of the pandemic’s effect on business ownership and that the burden fell disproportionately on business owners of color. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

Additional research on small business activity among racial and ethnic groups during the COVID-19 pandemic expands upon Fairlie’s work.8 Within this small body of work are a few additional studies that also used CPS data to examine related questions about small business owners of color. University of Missouri economist Jasper Grashuis, for example, assessed the relationship between a variety of business-owner characteristics and the risk of unemployment among these self-employed workers.9 His finds in his research, published in 2021, that between February 2020 and December 2020, business owners who were younger, female, and non-White were at greater risk of unemployment. Specifically, those self-employed workers identifying as Black, Asian American, or of mixed race in the Current Population Survey were at higher risk of unemployment than those identifying as White self-employed workers.10

A study published later in 2021 by Samuel Mindes of Iowa State University and Paul Lewin of the University of Idaho compares the prevalence of work interruptions for individuals in the wage sector to those in the self-employed sector of the U.S. economy from May 2020 through May 2021.11 They show that self-employed Black, Hispanic, and Native American workers reported being unable to work at higher rates than White self-employed workers. Immigrant self-employed workers were also more likely to report inability to work due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Interestingly, the co-authors find that college-educated self-employed workers were just as likely to face pandemic-related work interruptions as non-college-educated self-employed workers. Among wage workers, having a college education reduced this risk.

Early research by four social science researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles—Paul Ong, Andre Comandom, Nicholas DiRago, and Lauren Harper—examined a different angle of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on small businesses. They studied foot traffic patterns around restaurants and retail locations in different communities in Los Angeles (using location data from location data graphics firm SafeGraph) to compare that traffic in White and non-White neighborhoods.12 Even prior to the wave of pandemic-induced lockdowns, the four co-authors find evidence of the steepest declines in economic activity in the city’s Chinatown. After the onset of the pandemic, predominantly non-White neighborhoods experienced greater declines in foot traffic than the county overall.

More research is needed to understand whether and how rising anti-Asian sentiment before, and then amid, the pandemic impacted Asian American-owned small businesses or if the broader racial unrest during this time contributed to declines in demand for goods and services offered by these business owners.

Studies published later in the pandemic tap into other data sources as they became available. Shinae Choi and Erin Harrell from the University of Alabama joined Kimberly Watkins from the University of Georgia to examine the impact of COVID-19 on older entrepreneurs using data from the 2020 Health and Retirement Study.13 Their 2022 journal article shows that the pandemic adversely impacted 76 percent of older entrepreneurs with disproportionately negative effects among non-White older entrepreneurs.

More specifically, they find that older Black entrepreneurs faced the most severe outcomes, including higher odds of their businesses closing, more difficulty paying their bills, and higher instances of workers quitting. Older Hispanic and Asian American entrepreneurs likewise reported greater difficulty paying bills, while Hispanics also reported greater odds of workers quitting.

A few studies examined the experiences specifically of Latino-owned small businesses during the pandemic. Edward Vargas from Arizona State University and Gabriel R. Sanchez from University of New Mexico used the Abriendo Puertas/Latino Decisions National Parent Survey to examine the pandemic’s impact on business ownership and other outcomes.14 They find evidence that survey respondents were facing high rates of business closure, among other economic stressors, and further explore the impact on their well-being. Survey data showed that many Latinos were having difficulty with housing costs, foregoing education expenses, and postponing health-related services to cope with their harsh economic conditions.

Researchers at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative also examined the impact of COVID-19 on Latino-owned small businesses. They fielded several surveys to a large sample of Latino-owned firms, including follow-up surveys allowing them to observe the impact of the pandemic on these businesses over time. The percent of businesses reporting revenue declines more than doubled, from 31 percent in March 2020 to 74 percent in June 2020. Approximately 15 percent of businesses reported project delays in March, and by June, it rose to 42 percent.

The majority of these studies were released after the passage of the CARES Act in March 2020, which means that policymakers who needed to make decisions in real time were unable to benefit from the evidence in these findings. Moreover, scholars often had to use proxies to analyze business-owner dynamics, given the lack of available data. And because these studies are largely descriptive in nature, their analysis of the mechanisms underpinning the racial and ethnic outcomes during the pandemic is limited.

What’s more, studies that were able to unpack mechanisms that identified underlying racial and ethnic disparities tended to be geographically confined case studies. It is unclear how generalizable these cases are to the nation, even though the research clearly and consistently finds evidence of racial and ethnic disparities in the outcomes experienced by small business owners of color amid the COVID-19 pandemic. The next section of this report examines that historic legacy in detail to understand the pre-pandemic disparities in lending faced by small business owners of color.

Inequality in lending pre-COVID-19: The case of industry segregation

Some of the preexisting business characteristics of small businesses made them more vulnerable or more resilient to negative shocks from the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting recession. The extent to which these factors were distributed across or impacted businesses unequally due to the race or ethnicity of small business owners could explain a portion of the racial and ethnic disparities in business outcomes observed amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

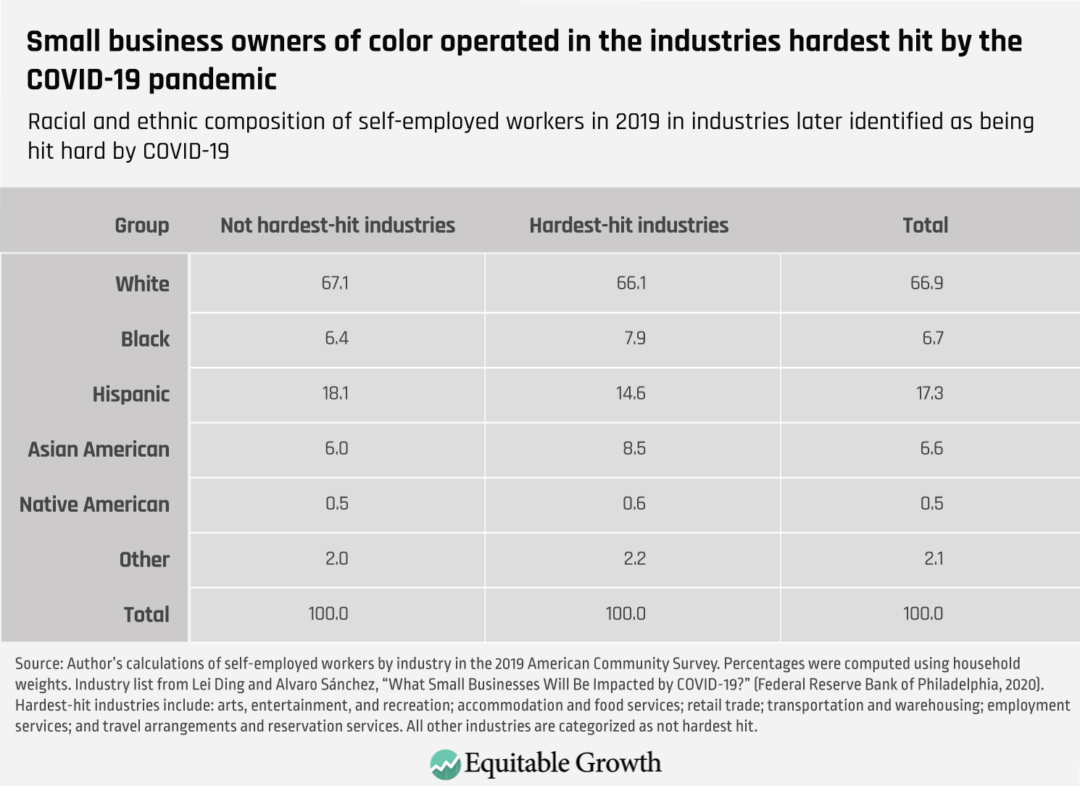

One structural factor faced by small business owners is industry segregation. The industries in which small businesses operate likely impacted their outcomes during the pandemic, since some industries were hit harder than others. If small business owners of color disproportionately operate in industries that were more vulnerable to the effects of the pandemic, then the data should show them to have worse outcomes, given this structural inequality.

In his analysis of CPS data, UC Santa Cruz economist Fairlie identified the industries with the largest declines in active business owners during the early months of the crisis.15 He then predicted what the change in business-owner activity would have been if each racial or ethnic group’s industry composition matched that of all U.S. small businesses, as these business owners experienced the actual percent change in activity across months. He then compared the predicted changes to the actual changes in business ownership by race and ethnicity.

The predicted change in business activity for White owners and Native American owners was very similar to the actual change, but there were dramatic differences in the predicted outcomes for small business owners of other races and ethnicities. Between February 2020 and April 2020, Black small business owners’ business activity fell by 41 percent, but if Black owners had the industry composition of all U.S. small business owners, then their business activity would have declined by 35 percent, reducing the Black-White disparity by 6 percentage points.

Similarly, if Latino small business owners had a more nationally representative industry composition, then their decline in business activity would have been closer to 28 percent rather than the 32 percent experienced. Asian American small business owners also would have had a smaller decrease in activity, from 26 percent to 22 percent, with a more representative industry composition.

Fairlie’s findings are further bolstered by a report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.16 Researchers there identified six industries that would be hit hardest by the COVID-19 crises, given their high share of self-employed workers—a proxy for small business owners—considered “at risk” due to the need for close contact. The industries included retail trade, transportation, employment services, travel arrangements, arts, entertainment and recreation, and accommodations and food service. The share of the small businesses in these sectors that were run by self-employed White workers was smaller than for businesses across industries that were not hit as hard by COVID-19. (See Table 2.)

Table 2

Structural inequality in industry compositions predating the pandemic explains a portion of the disparities we observe in business outcomes. But other sources for much of the variation remains unexplained. While more data are needed to investigate the causes of inequality, we can utilize prior data to identify other preexisting characteristics, structures, or systems that make businesses more vulnerable or resilient to negative shocks and then examine how those factors were distributed by race or ethnicity. The most important factor is financing.

Systemic barriers to financing pre-COVID-19 faced by small business owners of color

Financial resources play an essential role in the resiliency of small businesses. A decade ago, economists Timothy Bates at Wayne State University and Alicia Robb (then at the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation and now at UC Santa Cruz) explained that access to financing allows firms to weather the “liability of newness.”17 While new businesses are experimenting with operational procedures and adjusting to customer tastes, they require extra financial liquidity to meet their business obligations while they grow their revenue. Likewise, in order to weather or adapt during crises, businesses need access to sources of financing to continue paying expenses.

Indeed, during the COVID-19 pandemic, economists from Purdue University and the University of Missouri find that businesses that were undercapitalized going into the crisis were less resilient.18 They were more likely to experience severe losses in income and took a longer time to recover from pandemic-related economic losses if they managed to survive the crisis. So, if small business owners of color were less able to access capital before the pandemic, then the data should show that they were less resilient amid the pandemic.

A large body of research documents the difficulties that small business owners of color face when trying to access capital through the U.S. financial system.19 Well before the COVID-19 pandemic, evidence from numerous studies reveal that commercial banks, venture capital investors, and even crowdfunders provide disproportionately lower levels of funding to business borrowers of color. Some of these disparities can be attributed to structural factors, such as credit history or the racial wealth divide, but evidence of person-level discrimination also abounds.

Economists Alicia Robb at UC Santa Cruz and David Robinson at Duke University use data from the Kauffman Firm Survey of new small businesses to highlight the important role of commercial banks in small business finance.20 They show that commercial bank loans were the largest source of funding for new businesses in the survey, and that small business owners of color in the United States are underbanked and underserved by the commercial banking industry.21

One reason is that neighborhoods where people of color reside historically have had fewer bank branches, making it harder to form banking relationships.22 Research on bank locations in Chicago in 2018 showed that groups of neighborhood blocks with higher Black and Hispanic populations were less likely to have bank branches located there, even after controlling for local characteristics.23 These two historically disadvantaged groups also are less likely to have a bank account, less likely to be approved for a loan, and more likely to receive unfavorable terms when approved.24 And the large and persistent racial wealth divide means that many business owners of color have fewer assets to use as collateral for personal or commercial loans.25

There also is ample evidence of discriminatory lending practices. Older studies using data from the Survey of Small Business Finance by the Federal Reserve Board show that Black small business owners were twice as likely to be turned down for a loan than their White counterparts.26 These data allowed researchers to control for business and owner characteristics, including credit worthiness.

More recent analysis using the Kauffman Firm Survey showed that Black small business owners were three times less likely than their White counterparts to report that their loan applications were always approved.27 Economists Yue Hu and Long Liu at the University of Texas at San Antonio, along with Jan Ondrich and John Yinger of Syracuse University, matched Black and Hispanic small business owners with White small business owners on credit history, firm performance metrics, owner demographics, and loan characteristics to investigate fairness in lending.28 They find that the Black owners of small firms paid interest rates that were 0.79 percentage points higher than comparable White owners, while Hispanic owners paid rates that were 0.49 percentage points higher.

Despite laws forbidding lending discrimination, differential treatment persists. Utah State University professor Sterling Bone and his colleagues conducted an audit study of retail bank branches to test for race-based discrimination.29 They sent matched pairs of Black and White fictitious business owners to bank branches to inquire about small business loans. These testers were instructed to present nearly identical strong business profiles and credit histories.

The resulting study records statistically significant differences in the way testers were treated by bank loan officers. Black testers were asked to provide more information, including information that banks are not legally allowed to request. They were less likely to be offered preferred loan products and offered less assistance with the loan application process.

Given this persistent evidence of discrimination in lending, it is not surprising that so-called discouraged borrowing drives a portion of the observed divide in commercial lending to small business owners of color. Discouraged borrowing occurs when individuals do not apply for credit fearing they will be turned down. UC Santa Cruz’s Fairlie and his co-authors Alicia Robb at Next Wave Impact and Robinson at Duke University find higher levels of discouraged borrowing by Black small business owners in the Kauffman data, even when controlling for credit scores and net worth.30 Their results are stronger in regions of the United States with higher measures of racial bias.31

The Paycheck Protection Program: Implemented using a lending system with preexisting inequalities

The Paycheck Protection Program was one of the many policy interventions by the U.S. government during the COVID-19 pandemic. The federal government administered the program through the U.S. Small Business Administration. Congress allocated more than $800 billion in total funding tranches between April 2020 and March 2021 in the form of forgivable loans to businesses or nonprofit organizations with 500 or fewer employees.

The conditions for the funding were both generous and strict. Eligible small businesses could use the funding for payroll and other essential expenses, but the loans would only be forgiven if the business retained its employees or quickly rehired furloughed or laid-off workers. Loans were distributed to small businesses by private-sector lenders who were preapproved to participate in the Paycheck Protection Program.

During the early rounds of the PPP funding disbursements, this group of lenders was primarily composed of retail banks. Borrowers were not charged fees for the loans, but lenders were paid fees associated with loans by the federal government. Later tranches of funds approved by Congress included nonretail bank lending institutions, such as Community Development Financial Institutions, which lend to financially underserved communities, and so-called FinTech firms, which use online technology to compete with traditional retail banks.

By addressing the need for financial capital, the Paycheck Protection Program was the primary means through which the government provided relief to small businesses. Early media reports, however, indicated that larger, less vulnerable businesses and nonprofit institutions successfully acquired PPP funding, while many cash-strapped and often small business owners of color were unable to even apply before the first round of $349 billion in funding ran out.

This raised questions about the equitable distribution of PPP funds—questions that could not be answered comprehensively at the time due to a lack of data. Now, some of those data are available, and some preliminary research highlights the problem and promise of the Paycheck Protection Program for small business owners of color.

PPP loan applications by race and ethnicity

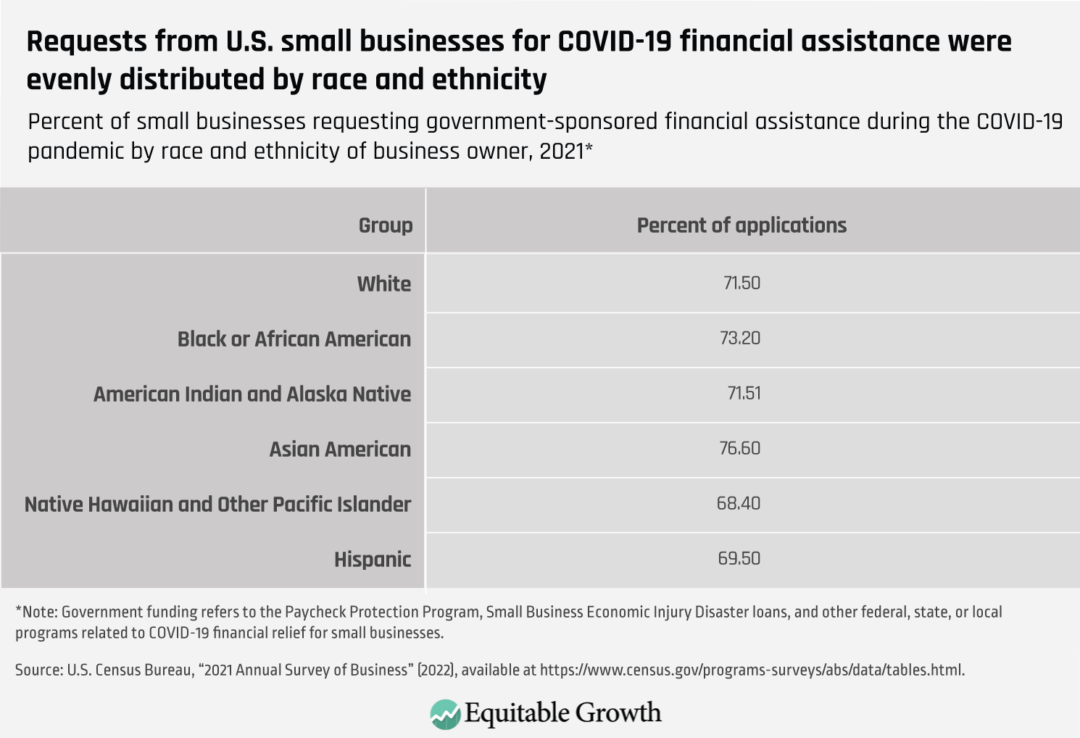

Since the Small Business Administration did not collect data on all PPP loan applications, the research on racial disparities in PPP lending does not take application rates into account. Given prior research findings about the prevalence of discouraged borrowers, one might question whether firms owned by Black and Latino small business entrepreneurs applied for the Paycheck Protection Program at lower rates than other groups. If true, then this could explain part of the reason why these groups received lower shares of PPP loans.

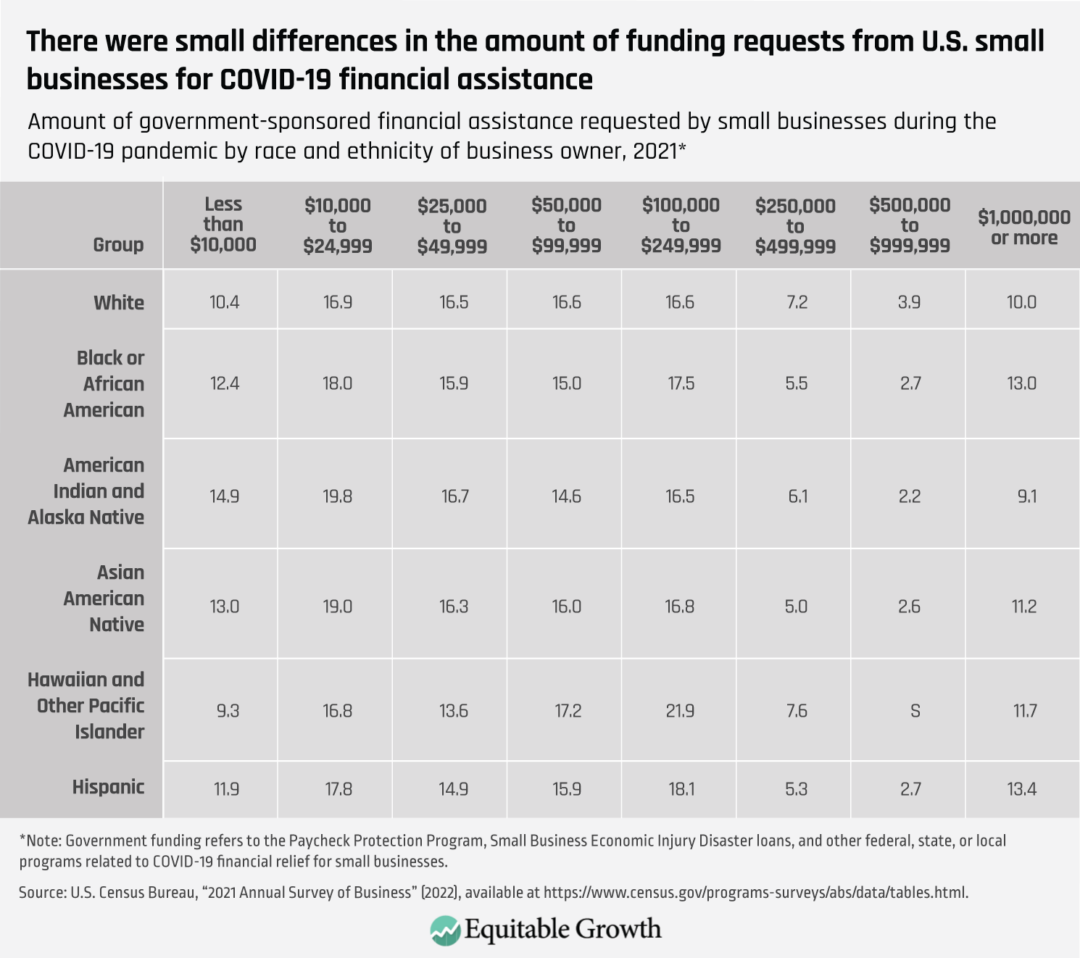

To explore this possibility further, I examined the preliminary release of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2021 Annual Business Survey, looking for businesses that requested government-sponsored financial assistance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Government funding in the survey refers to the Paycheck Protection Program, as well as to Small Business Economic Injury Disaster loans and other federal, state, or local programs related to COVID-19 financial relief for small businesses. Though the survey covers more than just PPP loan applications, these data provide a reasonable proxy for PPP application rates by race and ethnicity.

My research finds that differences were small between groups, and the majority of firms requested funding. Nearly 77 percent of Asian American-owned small businesses made requests, the highest request rate of any group in the data. More than 73 percent of Black-owned small businesses and 71.5 percent of White-owned small businesses reported requests for funding. Closely behind in percentage terms were American Indian and Alaska Native-owned firms (70.51 percent), Hispanic-owned firms (69.5 percent), and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander-owned firms (68.4 percent) requesting government funding during the pandemic. (See Table 3.)

Table 3

These data suggest that racial and ethnic differences in application rates were small, and since Black small business owners applied at higher rates than White small business owners, this offers some evidence that differences in application rates do not drive differences in loan distribution between Black-owned and White-owned firms. But I am not able to definitively rule out the possibility that these relatively small differences in loan application rates are related to racial disparities in the distribution of PPP loans for all groups without access to the microdata from this survey.

Newly released Annual Business Survey data do find, however, that there were racial disparities in the size of PPP loans approved. When I further examined whether there were racial differences in the distributions of loan amounts requested, I found that there were differences in observed characteristics, such as the size of the loans, which are likely correlated with the loan amounts firms would be eligible for and were likely to request. These data show that the distribution of funding requested among businesses was similar across racial and ethnic groups, though there was some variation.

Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander-owned small businesses were the most likely to request $100,000 or more in government funding, with 41 percent of these businesses doing so in 2021. American Indian and Alaska Native-owned firms were the least likely to request these large sums of funding (34 percent), while 36 percent of Asian American-owned firms requested $100,000 or more of funding. White-, Black-, and Hispanic-owned firms all had similar request rates of 40 percent, 39 percent, and 40 percent, respectively. (See Table 4.)

Table 4

These data do not suggest that there were significant differences in the loan amounts requested, but I am not able to draw definitive conclusions without the microdata from this survey.

The earliest evidence of more discernable inequality in the distribution of PPP loans is seen in the distribution of these funds by neighborhoods, even though these data do not identify who received the loans by race or ethnicity. Paul Calem and Adam Freedman of the Bank Policy Institute examined data on PPP loans from the first two rounds of funding, between April 2020 and August 2020. They report that relatively large shares of the PPP funds went to neighborhoods with high shares of residents from historically disadvantaged racial and ethnic groups.32 But they note the results were not statistically significant for neighborhoods with majority African American populations.

Another study by economists Fairlie of UC Santa Cruz and Frank Fossen at the University of Nevada, Reno also analyzed data from the first two PPP rounds of funding.33 They find that while PPP loans were slightly more likely to be distributed in neighborhoods with higher shares of non-White residents, the amount of funds that flowed to these neighborhoods during the second round of funding, as well as the loan amounts, were smaller.

Other evidence from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Small Business Pulse Survey found that the severity of COVID-19 in an area was unrelated to the approval rate for PPP loan applications.34 Research from Mary Beth Kelly and Eric Joseph van Holms at the University of New Orleans finds that communities with larger numbers of COVID-19 cases received fewer loans while those communities with more White residents, higher incomes, and less urban counties received more loans.35 This suggests that, at minimum, small businesses in areas hardest hit by COVID-19 were no more likely to receive relief than areas that were not.

This analysis provides more early evidence that relief might not have reached small businesses in these neighborhoods because other data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that racial and ethnic historically disadvantaged communities were hardest hit by COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021.36

Subsequent studies used the data released by the Small Business Administration to examine racial disparities in PPP lending. My work with economists Lisa Cook (then at Michigan State University and now on the Federal Reserve Board) and Robert Seaman at New York University’s Stern School of Business examined differences in loan amounts between Black and White PPP loan recipients.37 We show that even after controlling for observable characteristics, such as location and firm size, Black-owned small businesses received loans that were approximately 50 percent lower than observationally similar White-owned small businesses.

Then, there’s some key microeconomic evidence of racial and ethnic disparities in PPP loan distributions in recent research by Sergey Chernenko at Purdue University’s Krannert School of Management and David Scharfstein at Harvard Business School. They investigated racial disparities in PPP loans among Florida restaurants. They find that Black-owned restaurants were 25 percent less likely to receive PPP loans from banks,38 Hispanic-owned restaurants were 9 percent less likely to receive PPP loans, and Asian American-owned restaurants were 2 percent less likely to receive PPP funds than White-owned restaurants.

Moreover, Chernenko and Scharfstein find that while racial and ethnic differences in the location of restaurants, the characteristics of those establishments, and the preexisting banking relationships of the restaurant owners contributed to these disparities, another measure of racial bias played a significant role in driving the inequality they observed. Using county-level data from the social cognition research nonprofit organization Project Implicit on levels of implicit and explicit racial bias, the authors find that a one standard deviation increase in explicit bias reduced the likelihood of a Black-owned business receiving a PPP loan by nearly 14 percentage points.

Their analysis attributed 10 percentage points of the gap between Black-owned and White-owned small businesses receiving PPP loans to racial differences in restaurants’ observed characteristics. Observed characteristics include the owner’s gender, the number of seats in the establishment, the age of the firm, whether it accepts credit cards, and its reviews, ratings, activity volume, and webpage views. An additional 5 percentage points were attributed to the location of the restaurants. Local differences consisted of differences in bank branches near the restaurant, the number of COVID-19 cases in the restaurant’s neighborhood, and the per-capita income of the communities in which the restaurant was situated.

Another recent working paper by Isel Erel at The Ohio State University’s Fisher College of Business and Jack Liebersohn at the University of California, Irving also finds evidence that location differences or segregation contributed to the unequal allocation of PPP funds.39 They find that FinTech firms were primarily used in ZIP codes with fewer bank branches, lower incomes, higher minority populations, and where retail banks were making fewer PPP loans.

Unequal flows of information also contributed to the observed racial disparities in PPP lending. Analysis using data from a daily survey of U.S. businesses conducted by economists John Eric Humphries at Yale University, Christopher A. Neilson at Princeton University, and Gabriel Ulyssea at the University of Oxford finds that smaller businesses were less aware of the Paycheck Protection Program and were therefore less likely to apply.40 They find that among businesses that did apply, the smaller businesses tended to do so later than larger firms, were more likely to have longer processing times, and were less likely to be approved. While this analysis did not include information on the race or ethnicity of the borrower, we know that small business owners of color tend to have smaller firms than their White counterparts due to undercapitalization.41

Evidence from audit studies further explains the information gaps about the Paycheck Protection Program by race and ethnicity. Researchers from the National Community Reinvestment Coalition and their academic partners shows that during the COVID-19 pandemic, loan officers from commercial lending institutions in the Washington, DC area provided different degrees of information to testers of different racial groups.42 They find statistically significant differences in the level of encouragement to apply for a loan, the products offered, and the information provided by the bank representative based on the race of the tester.

Economists Raffi Garcia at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and William Darity Jr. at Duke University also find evidence of discrimination in PPP lending.43 They use hand-collected data on the race of small business owners and find evidence that choosing not to disclose one’s race led to better outcomes for borrowers. Small businesses owned by Black entrepreneurs who chose not to disclose their race received 52 percent more loan funding than those who did disclose their race. By contrast, they do not find statistically significant differences for White borrowers based on the disclosure of their race.

Relationship lending may be another mechanism that introduced bias into the PPP lending program. New research by Ran Duchin at Boston College’s Carroll School of Management, Xiumin Martin and Hanmeng Ivy Wang at the Olin School of Business at Washington University in St. Louis, and Roni Michaely at the University of Hong Kong analyzed data on public firms that received PPP funding.44 Their research finds that businesses with personal ties to banks were more likely to acquire PPP loans. We know from pre-pandemic research that small business owners of color were less likely to have existing banking relationships and therefore less likely to be preferred borrowers in the program.45

Additional analysis by the four co-authors of the role that relationship lending played in PPP loan allocation finds that lenders tended to prioritize businesses with existing relationships in order to limit their own liability. More specifically, they find that financial institutions seeking to minimize defaults among their current borrowers were more likely to extend PPP loans to this group of applicants. Interestingly, the four co-authors also find these relationships were associated with higher rates of PPP rule violations by borrowers. This research highlights the role that favoritism played in allocating PPP loans.

Course corrections made PPP distribution modestly more equitable

In response to outcries from small business owners in general, and historically disadvantaged small business owners of color in particular, the U.S. Congress made several changes to the way subsequent rounds of PPP funds were administered. During the second round of PPP funding, administered from April 27, 2020 to August 8, 2020, the Small Business Administration approved approximately 600 additional lenders to the program. Importantly, this expanded the number and types of lenders who were eligible to provide PPP funding to include nondepository institutions.46 This change was expected to reduce bias in access to the program so that small business owners who may not have been preferred borrowers for retail banks could acquire funds through other institutions.

These new PPP lenders included Community Development Financial Institutions that specialize in lending to financially underresourced communities. These institutions have historically made 65 percent of their funding available to underserved communities, including low-income borrowers and borrowers of color.47 Another set of new PPP lenders were so-called FinTech firms that compete online with more traditional retail banks.

This course correction mostly worked. Research by Ohio State’s Erel and UC Irvine’s Liebersohn finds that loans originated from FinTech firms were disproportionately distributed to ZIP codes with fewer retail bank branches.48 This suggests that a lack of local bank branches may have hindered PPP lending in some neighborhoods without the expansion of SBA-approved lenders to include these nontraditional institutions.

My most recent research with Michigan State’s Cook and NYU’s Seamans underscores the findings of Erel and Liebersohn. The three of us examined the differences in the amounts of PPP loans disbursed by retail banks and FinTech firms.49 While we do find evidence of disparities in lending to small business owners of color among FinTech firms, these disparities are substantially smaller in magnitude than the disparities we observe in loans initiated by retail banks. We attribute this difference to FinTech firms’ use of algorithms and automation, which remove some biases that would otherwise be introduced through human interaction at local bank branches. More research is needed to unpack the role of CDFIs in PPP lending.

The persistence of these racial and ethnic disparities in lending to small business owners of color, though to a smaller degree even among nonretail banking institutions, indicates that there may still be some racial biases present in the lending process even when it is automated. More research is necessary to better understand the role technology may play both in potentially eliminating racial biases and in perpetuating them.

But one factor limiting the analysis of racial disparities in the Paycheck Protection Program using the data collected by the Small Business Administration is that much of the information on race or ethnicity of business owners is missing. While our analysis used statistical methods to address the missing data problem, other scholars used algorithms to predict the race of borrowers when data were missing. Work from NBER faculty research fellow Sabrina Howell and her colleagues used one such algorithm in their studies.50 They show that Black small business owners were more likely to receive PPP funding through FinTech firms than from traditional banks.

Moreover, they find evidence that lower human bias in decision-making is one mechanism facilitating PPP loan access to this group of borrowers. In fact, Howell and her co-authors find that when retail banks turned to automated lending practices, their lending to Black small business owners increased, too.

These research findings indicate that automated lending systems and the participation of FinTech firms may have removed a portion of racial bias from the PPP implementation process in the second round of PPP funding, providing indirect evidence that the lending discretion of loan officers may have led to racial disparities in PPP lending. It also illustrates how programmatic changes that address existing biases in systems can produce more equitable outcomes.

Conclusion and policy recommendations

Considering what the research says about the COVID-19 pandemic and the Paycheck Protection Program, policymakers could improve upon this kind of program if initiated again due to a similar crisis in the future or more broadly in overall lending to small businesses to obliterate structural racial inequality and systemic racial bias in lending practices. There are several ways to achieve the same aims now and in the future.

First, in response to a new crisis, policymakers must design for preexisting racial biases within the U.S. financial system before rolling out a new type of Paycheck Protection Program. Despite the mountain of evidence that retail banks continue to underserve small business owners of color and the communities they serve, the Small Business Administration used this group of lenders as the primary distributor of PPP funds when vulnerable businesses needed them most. Well before the next crisis, the agency should examine how existing systems, institutions, and norms reinforce discrimination and design programs to be implemented around these systems and structures rather than through them.

On a more positive note, the research conducted on the distribution of PPP funds also illustrated how officials can minimize bias by utilizing a more diverse group of financial resource providers and by targeting vulnerable communities. Alternatively, the federal government has mechanisms in place to distribute cash benefits directly to small businesses, cutting out intermediary private-sector financial institutions. For instance, Congress should consider making direct payments to businesses during future crises rather than relying on third parties. Because the federal government already possesses much of the information used to determine whether businesses qualified for PPP loan forgiveness and for how much, it might have been able to provide relief in a timelier manner and with more precision by making cash payments rather than convertible loans.

To respond quickly to future crises, policymakers should consider making investments in information systems that would conduct the necessary analysis and transactions, so that federal entities such as the Small Business Administration and U.S. Treasury Department could engage in this kind of emergency lending to small businesses. Of course, such reforms would need to be initiated and supported by congressional and executive branch officials.

Policymakers also should invest in greater enforcement of anti-discrimination laws already on the books. The performance of the Paycheck Protection Program illustrated that even when faced with zero risk, financial institutions continue to discriminate against people of color. Thus, lawmakers should require and fund increased surveillance of lending activity by financial institutions to hold them accountable to anti-discrimination laws and policies. This may not only improve access to credit among loan applicants, but also build trust in the financial system, reducing the number of discouraged borrowers.

Finally, lawmakers must commit to increasing investment in digital infrastructure within historically marginalized communities. The benefits will not only reach business owners of color in these communities but also residents and students who struggled during lockdowns when they were cut off from high-speed internet services. Beyond times of crises, such investments will pay dividends in prosperous times, enabling the kinds of wealth-generating activity from small business owners of color that can spur economic growth in communities for generations to come.51

Opportunities for future research

The body of research on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on businesses owned by historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups is small but growing, though perhaps not quickly enough. Much of what researchers know centers on the initial impacts at the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, but what we lack are insights into its long-term effects on these businesses, the individuals who own them, the workers they employ, and the customers they serve.

For instance, little is known about the mechanisms through which the pandemic caused the observed disparate impacts on small business owners of color. How much did the disparities in health-related outcomes contribute to disparities in business outcomes by race and ethnicity? Did variation in stay-at-home orders and designation of essential versus nonessential businesses disparately impact small business owners of color? How did preexisting structural inequalities make these businesses more vulnerable to the crisis?

Future study of pre-COVID-19 structural inequality and future outcomes

In addition to industry segregation described earlier in this report, geographic segregation is another structural factor that may have contributed to unequal COVID-19 outcomes for businesses by race or ethnicity of the owners. The effects of the pandemic were not disbursed evenly across the country. Some states and municipalities were hit harder than others.52 Communities of color were, at least initially, among the hardest hit in terms of COVID-19 test positivity rates, hospitalizations, and deaths.53

So, hypothetically, states with higher shares of small business owners of color prior to the pandemic were more adversely affected by the pandemic in its first two years, which means geographic distribution of business owners by race and ethnicity could explain a portion of the disparities in pandemic-related outcomes. More research is needed to examine whether and how residential segregation contributed to racial differences in the pandemic’s effect on small business owners of color.

Access to broadband is another structural factor related to geographic segregation that may have produced racial and ethnic inequalities. The digital divide negatively impacted students of color and their ability to engage in remote learning amid the pandemic.54 Likewise, the underinvestment in digital infrastructure may have had negative consequences for small business owners of color by limiting their ability to effectively operate digitally during stay-at-home orders, state and local restrictions on business operations, and customer reluctance to engage in face-to-face commercial activity.

Indeed, early empirical findings from David Audretsch at Indiana University, Diana Heger at the Centre for European Economic Research, and Tobais Veith at the University of Applied Sciences Rottenberg showed that while infrastructure in general was positively related to new business activity, the relationship with broadband infrastructure was even more positive.55

Further research is needed to unpack how access to broadband infrastructure may have altered the pandemic-related outcomes of small business owners of color. Broadband facilitates the use of other digital technologies that require high-speed internet services to operate at a high capacity. Rather than needing to have adequate server capacity on site, businesses can readily take advantage of cloud-based computing to operate digitally at a lower cost.

Moreover, access to these technologies and experience utilizing them made it easier for some businesses to transition to the virtual environment during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Racial differences in access to and experience with these technologies may have also contributed to observed disparities in outcomes. Further research is needed to examine these hypotheses systematically. (See Appendix 1 for preliminary analysis.)

More data and research are needed

That structural racial inequality among business owners pre-COVID-19 would lead to disparate outcomes during the pandemic is a logical and compelling argument, but it must be supported by evidence. More research is needed to show theoretical linkages empirically.

Yet a lack of access to the types of data that allow researchers to draw these causal links limits researchers’ ability to advance knowledge about the outcomes of business owners of color during the COVID-19 crisis and the mechanisms producing those outcomes. Since the business datasets produced by the U.S. Census Bureau are not longitudinal in nature, researchers are not able to follow businesses over time to evaluate whether racial differences in key variables explain differences in outcomes, such as business survival, income, or profitability.

Some researchers have been able to link U.S. Census Bureau survey data to data from the IRS on outcomes that allow researchers to follow firms over time. Unfortunately, due to privacy concerns, not enough researchers have access to these data, and important policy-relevant questions remain unanswered. Lawmakers should push policies that expand access to data while protecting privacy. This may mean creating more pathways for researchers to analyze sensitive data in secure settings or experimenting with new data products that make relevant information more readily available in de-identified formats.

One other reason that new research may be slow in coming is the lack of timely data. While the Current Population Survey has the benefit of being a very timely data source, it is limited in several ways. First, it is an individual-level dataset and therefore does not provide information on businesses. It surveys individuals several times over the course of months, which helps researchers follow business owners over a short period of time but limits our ability to see how they fare over medium-term or longer time periods. The Current Population Survey also does not include detailed questions on wealth or health, thus limiting the types of outcomes we can use it to measure.

Data sources that do include some of this information on businesses, households, wealth, or health either lack information on race and ethnicity or are collected and released with longer lags such that we cannot observe outcomes in real time. The Census Bureau’s Small Business Pulse Survey, for example, was an experimental data product that provided timely data on changing conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. But it did not report information on the race and ethnicity of business owners.

The U.S. Census Bureau also publishes data from its Annual Businesses Survey, which includes some of the most detailed information available on small businesses. Due to lags in data collection and release, it is less helpful for understanding difficulties that small business owners of color face in real time. What’s more, the Census Bureau releases a limited set of tables from the Annual Businesses Survey but does not release the microdata from this survey, which restricts the ability to analyze available data by the race or ethnicity of business owners.

Other datasets collected by the Federal Reserve Board provide useful information on self-employed workers by race and ethnicity. The Survey of Consumer Finances reports detailed information on respondents’ wealth and borrowing activity. The Survey of Household Economic Decisionmaking even asks respondents if they experienced racial discrimination over the prior 12 months.

Recently released data from these surveys will provide more detailed information on the experiences of small business owners of color during the early days of the pandemic, but these surveys have limitations, too. The lack of publicly available geographic information complicates the analysis of racial and ethnic disparities, especially since business owners in different parts of the United States faced very different conditions amid the pandemic. Moreover, as with other detailed surveys discussed above, the lag between the time of data collection and release prevents policymakers from utilizing this information to make decisions mid-crisis.

Greater coordination between federal, state, and local governments with academic and other research institutions may help bridge these knowledge gaps in a timelier fashion. By forging preexisting relationships with scholars at universities and research institutions, the Census Bureau can expand its capacity to analyze data on businesses owned by people of color that cannot be released publicly. The set of systems and structures rightly designed to protect the privacy of survey respondents erects barriers to timely data analysis that could inform public policy in times of crisis.

Preapproved scholars could, if granted access, analyze data that may be preliminary in nature but provide some information on the experiences of vulnerable business owners during ongoing crises. Establishing more cohesive research networks and partnerships would also allow private higher education or research institutions to share data with government entities to inform policy in a timely manner. Importantly, the network of researchers also should reflect the racial and ethnic composition of the communities being studied in the research. The theoretical perspectives and methodological approaches of marginalized scholars are crucial to informing policies that promote equity.

Finally, expanding access to Census Bureau data products will not increase and improve the body of research on small business owners of color if the quality of existing data is diminished. The Census Bureau has announced plans to alter their public-use data products such that “intentional errors” would be “added to nearly all statistics, including even the total populations of all geographic units below the state level.”56 These measures would be undertaken in order to address privacy concerns, even though “the threat of database reconstruction was minimal …[t]he Census Bureau’s attempt to reconstruct the 2010 Census from published tabulations was incorrect in most cases, and did not perform much better than random guesses of people’s characteristics.”57

Much of the analysis advocated for in this report would be impossible to conduct should the proposed changes go into effect in perpetuity. Without quality Census Bureau data, policymakers, planners, scientists, and others will lack crucial information on the changing demographics of the U.S. population. Federal officials must therefore act to protect the quality of the public use of decennial census and American Community Survey data. Failure to act will significantly impair the ability to evaluate the effectiveness of future government programs and assess whether economic prosperity is equitably enjoyed across all racial and ethnic groups in the United States.

Appendix 1: Characteristics, capabilities, and COVID-19

A firm’s ability to effectively pivot to remote operations requires more than just broadband access, but also knowledge and experience operating digitally. Businesses functioning in digital spaces prior to the COVID-19 pandemic were arguably more prepared for fully remote environments and thus better able to navigate operations through the pandemic and its related public policy responses. Racial and ethnic differences in digital business activity prior to the pandemic may explain a portion of the differences we observe in negative pandemic-related outcomes by race.

Using data from the 2016 and 2017 Annual Survey of Entrepreneurs on employer firms in the United States, I examined three categories of digital operations to assess the digital divide among business owners by race and ethnicity: digital share of business operating activity, share of businesses with a website, and the share of business sales completed using e-commerce.

Firms would need to have important operating information in digital form prior to moving their employees to remote work. Businesses that were already utilizing digital forms of information and communication along key operating functions would have made this transition more easily. The 2017 Annual Survey of Entrepreneurs collects data on the percent of personnel, financial, customer, marketing, supply chain, production, and other information that businesses kept in digital formats. Table A1 reports this information by the race or ethnicity of the business owner.

Table 1A

Between 76 percent and 90 percent of White-owned firms kept business information in digital formats. Black-owned and Hispanic-owned firms were less likely than White-owned ones to keep information digitally across all categories. Hispanic-owned firms were 3 percentage points to 5 percentage points less likely and Black-owned firms were 2 percentage points to 3 percentage points less likely to do so, compared to their White-owned counterparts.

Differences were smaller for Asian American, Pacific Islander, and Native American business owners, with a few notable exceptions. Asian American business owners were 4 percentage points less likely to keep financial information digitally and Pacific Islanders were 4 percentage points less likely to keep digital supply chain information. Asian American business owners were more likely to keep customer feedback information in digital form, but only by 2 percentage points.

In addition to having information in digital formats, businesses must also be able to operate and communicate in the virtual environment. Having a company website prior to the pandemic may be useful proxy for a business’s prior virtual presence. The 2016 Annual Survey of Entrepreneurs asked business owners whether they had a website. Thirty-seven percent of Asian American business owners reported having a website, the smallest share among all racial and ethnic groups. Among Hispanic owners, 46 percent reported having a company website. Half of all Black-owned businesses had websites, as did 54 percent of Native American ones and 53 percent of Pacific Islander-owned firms. The highest rates were reported by White business owners, 57 percent of whom reported having a website in the 2016 survey. Table A2 reports the responses by the race or ethnicity of the business owner.

Table 2A

Finally, businesses must be able to collect revenue to survive. Thus, firms needed to be able to generate e-commerce sales during pandemic-related lockdowns and thereafter to stay afloat. Businesses already engaged in e-commerce prior to the pandemic were likely better-positioned for survival.

The 2016 Annual Survey of Entrepreneurs also collected data on the percent of sales a business accrued via e-commerce. Despite roughly half of businesses reporting having websites, a fraction of those reported any e-commerce sales. Twelve percent of Native American- and White-owned businesses reported some e-commerce sales in the 2016 survey. For businesses owned by Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, 10 percent reported e-commerce sales. Eight percent of Black and Hispanic business owners also reported e-commerce sales.

Differences in e-commerce sales are more dramatic for some of the industries hit hardest by the pandemic and its corresponding shutdowns. While nearly a quarter of White-, Black-, and Native American-owned retail trade businesses reported e-commerce sales in 2016, only 15 percent of Hispanic-owned small businesses and 10 percent of Asian American-owned small businesses did so. A third of all Pacific Islander-owned firms reported e-commerce sales.

In arts and entertainment, only 11 percent of Black-owned businesses had e-commerce sales, while 20 percent to 25 percent of businesses from other groups did so. Hispanic-owned accommodations and food-services businesses reported the smallest share of businesses with e-commerce sales, at 8 percent, compared to 13 percent to 15 percent for most other groups. Only 1 percent of Pacific Islander-owned firms reported e-commerce sales in the accommodation and food-service industry. Table A3 displays this information by the race or ethnicity of the business owner.

Table 3A

Taken together, these data show variation in the extent to which firms across racial groups were operating digitally 5 years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. But this analysis is limited by the coarseness of these data. Since the U.S. Census Bureau does not provide microdata on this information, I cannot examine whether racial and ethnic differences persist when controlling for observable characteristics. Without microdata, I cannot control for observable characteristics of the businesses or their owners to understand what explains racial and ethnic differences where present.

Importantly, these data were collected 5 years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Without any insights into the growth in technology adoption since then, it is hard to know the nature of the digital divide just prior to the crisis. If firms from historically marginalized groups faced slower growth in technology adoption, then the gaps may be even wider today. Alternatively, if they gained access to and adopted digital technologies at a faster rate, then it would indicate that, rather than access to technology or technical skill, other factors were more salient in explaining the disproportionately negative outcomes that small business owners of color experienced. More recent data in more granular forms are needed to answer these and other questions.

About the author

Rachel Marie Brooks Atkins is an assistant professor of economics at St. John’s University’s Tobin School of Business. Previously, she was a provost’s doctoral fellow in the management and organizations department at New York University’s Stern School of Business. Her research examines racial economic inequity in entrepreneurship, organizations, and high-tech industries. She also studies the effect of public policies on racial inequality in those contexts. Atkins earned her Ph.D. in public and urban policy from the New School. She previously earned an M.P.A from New York University, a master’s in government administration from the University of Pennsylvania, and a B.S. in economics from West Chester University of Pennsylvania.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Raffi Garcia at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and Gregory Price at the University of New Orleans for their very helpful reviews of earlier drafts of this report.

End Notes

1. Robert W. Fairlie, “The impact of COVID‐19 on small business owners: Evidence from the first three months after widespread social‐distancing restrictions,” Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 29 (4) (2020): 727–740, available at https://doi.org/10.1111/jems.12400.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, H.R.748, 116th Cong. 2nd sess. (Government Printing Office, 2020), p.13, available at https://www.congress.gov/116/bills/hr748/BILLS-116hr748enr.pdf.

5. Drew Dahl and William R. Emmons, “Was the Paycheck Protection Program Effective?,” The Regional Economist (2022), available at https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/2022/jul/was-paycheck-protection-program-effective.

6. Fairlie, “The impact of COVID‐19 on small business owners: Evidence from the first three months after widespread social‐distancing restrictions.”

7. Ibid.

8. Robert W. Fairlie and Frank Fossen, “The 2021 Paycheck Protection Program Reboot: Loan Disbursement to Employer and Nonemployer Businesses in Minority Communities.” Working Paper. (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2022), available at https://doi.org/10.3386/w29732; Tayo Korede and others, “Exploring innovation in challenging contexts: The experiences of ethnic minority restaurant owners during COVID-19,” The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation (2021); Yasuyuki Motoyama, “Is COVID-19 Causing More Business Closures in Poor and Minority Neighborhoods?,” Economic Development Quarterly (2022).

9. Jasper Grashuis, “Self-employment duration during the COVID-19 pandemic: A competing risk analysis,” Journal of Business Venturing Insights 15 (2021): e00241, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2021.e00241.

10. Ibid.

11. Samuel C.H. Mindes and Paul Lewin, “Self-employment through the COVID-19 pandemic: An analysis of linked monthly CPS data,” Journal of Business Venturing Insights 16 (2021): e00280, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2021.e00280.

12. Paul Ong and others, “COVID-19 Impacts on Minority Businesses and Systemic Inequality” (Los Angeles: UCLA Center for Neighborhood Knowledge, 2020), p. 31.

13. Shinae L. Choi, Erin R. Harrell, and Kimberly Watkins, “The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Business Ownership Across Racial/Ethnic Groups and Gender,” Journal of Economics, Race, and Policy 5 (2022): 307–317, available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s41996-022-00102-y.

14. Edward Vargas and Gabriel R. Sanchez, “COVID-19 Is Having a Devastating Impact on the Economic Well-being of Latino Families,” Journal of Economics, Race, and Policy 3 (4) (2020): 262–269, available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s41996-020-00071-0.

15. Fairlie, “The impact of COVID‐19 on small business owners: Evidence from the first three months after widespread social‐distancing restrictions.”

16. Lei Ding and Alvaro Sánchez, “What Small Businesses Will Be Impacted by COVID-19?” (Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, 2020).

17. Timothy Bates and Alicia Robb, “Greater access to capital is needed to unleash the local economic development potential of minority-owned businesses,” Economic Development Quarterly 27(3) (2013): 250–259.

18. Bhagyashree Katare, Maria I. Marshall, and Corrine B. Valdivia, “Bend or break? Small business survival and strategies during the COVID-19 shock,” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 61 (2021): 102332, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102332.

19. Bates and Robb, “Greater access to capital is needed to unleash the local economic development potential of minority-owned businesses”; Robert Fairlie, Alicia Robb, and David T. Robinson, “Black and White: Access to Capital Among Minority-Owned Start-ups,” Management Science 68 (4) (2022), available at https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2021.3998; Timothy Bates and William D. Bradford, “Venture‐Capital Investment in Minority Business,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 40 (2‐3) (2008): 489–504; Susan Coleman, “Access to debt capital for women-and minority-owned small firms: Does educational attainment have an impact?,” Journal of developmental entrepreneurship 9 (2004): 127-144; Mondor Ram and others, “Banking on ‘break-out’: Finance and the development of ethnic minority businesses,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 29 (4) (2003): 663–681; Neil Lee and Emma Drever, “Do SMEs in deprived areas find it harder to access finance? Evidence from the UK Small Business Survey,” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 26 (3-4) (2014): 337–356; Rachel Atkins, Lisa Cook, and Robert Seamans, “Discrimination in lending? Evidence from the Paycheck Protection Program,” Small Business Economics 58 (2) (2022): 843–865; Sabrina Howell and others, “Automation and Racial Disparities in Small Business Lending: Evidence from the Paycheck Protection Program.” Working Paper No. 29364 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021), available at https://doi.org/10.3386/w29364; Raffi E. García and William A. Darity Jr., “Self-Reporting Race in Small Business Loans: A Game-Theoretic Analysis of Evidence from PPP Loans in Durham, NC,” AEA Papers and Proceedings 112 (2022).

20. Alicia M. Robb and David T. Robinson, “The Capital Structure Decisions of New Firms,” Review of Financial Studies 27 (1) (2014): 153–179, available at https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhs072.

21. Ibid.

22. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, “2017 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households” (2011), p. 96; Elyas Elyasiani and Lawrence G. Goldberg, “Relationship lending: a survey of the literature,” Journal of Economics and Business 56 (4) (2004): 315–330.

23. Scott W. Hegerty, “Banking Deserts,” Bank Branch Losses, and Neighborhood Socioeconomic Characteristics in the City of Chicago: A Spatial and Statistical Analysis,” The Professional Geographer 72 (2) (2020): 194–205, available at https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2019.1676801. Neighborhoods were measured using the Census Block Group geographic designation.

24. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “Availability of Credit to Small Businesses,” (2017) https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2017-september-availability-of-credit-to-small-businesses.htm?utm_source=pocket_saves; Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, “2017 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households,” p. 96.

25. Rachel M.B. Atkins, “Homeownership, home equity, and Black-owned business starts: Examining the impact of racial disparities in housing assets on firm creation,” (2021), p. 33.

26. David G. Blanchflower, Phillip B. Levine, and David J. Zimmerman, “Discrimination in the Small-Business Credit Market,” The Review of Economics and Statistics 85 (4) (2003): 930–943, available at https://doi.org/10.1162/003465303772815835.

27. Fairlie, Robb, and Robinson, “Black and White: Access to Capital Among Minority-Owned Start-ups.”

28. Y. Hu and others, “The Racial and Gender Interest Rate Gap in Small Business Lending: Improved Estimates Using Matching Methods” (2011), p. 38.

29. Sterling A. Bone and others, “Shaping small business lending policy through matched-pair mystery shopping,” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 38 (3) (2019): 391–399.

30. Fairlie, Robb, and Robinson, “Black and White: Access to Capital Among Minority-Owned Start-ups.”

31. Ibid. Fairlie, Robb, and Robinson construct an instrument for racial bias using the prevalence of interracial marriages within a state. Attitudes toward interracial marriage are shown to be negatively related to measures of racial bias and income disparities. See Kerwin Kofi Charles and Jonathan Guryan, “Prejudice and wages: An empirical assessment of Becker’s The Economics of Discrimination,” Journal of political economy 116 (5) (2008): 773–809.

32. Paul Calem and Adam Freedman, “Neighborhood Demographics and the Allocation of Paycheck Protection Program Funds.” SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 3776794 (Social Science Research Network, 2020), available at https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3776794.

33. Robert Fairlie and Frank M. Fossen, “Did the Paycheck Protection Program and Economic Injury Disaster Loan Program get disbursed to minority communities in the early stages of COVID-19?” Small Business Economics 58 (2) (2022): 829–842, available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00501-9.

34. Meng Li, “Did the small business administration’s COVID-19 assistance go to the hard hit firms and bring the desired relief?” Journal of Economics and Business 115 (2020): 105969, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconbus.2020.105969.

35. Mary Beth Kelly and Eric Joseph van Holm, “Urbanization, Community Demographics, and the Distribution of Paycheck Protection Program Loans Across Counties.” SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3801348 (Social Science Research Network, 2021), available at https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3801348.

36. Gregorio A. Millett and others, “Assessing differential impacts of COVID-19 on black communities,” Annals of epidemiology 47 (2020): 37–44.

37. Atkins, Cook, and Seamans, “Discrimination in lending? Evidence from the Paycheck Protection Program.”

38. Sergey Chernenko and David S. Scharfstein, “Racial Disparities in the Paycheck Protection Program.” Working Paper No. 29748 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2022), available at https://doi.org/10.3386/w29748.

39. Isil Erel and Jack Liebersohn, “Does FinTech Substitute for Banks? Evidence from the Paycheck Protection Program.” Working Paper No. 27659 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020), available at https://doi.org/10.3386/w27659.

40. John Eric Humphries, Christopher A. Neilson, and Gabriel Ulyssea, “Information frictions and access to the Paycheck Protection Program,” Journal of Public Economics 190 (2020): 104244, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104244.

41. Timothy Bates, “The urban development potential of black-owned businesses,” Journal of the American Planning Association 72 (2) (2006): 227–237.

42. Anneliese Lederer and Sara Oros, “Lending discrimination within the paycheck protection program,” (National Community Reinvestment Coalition, 2020), available at https://ncrc.org/lending-discrimination-within-the-paycheck-protection-program/.

43. García and Darity Jr., “Self-Reporting Race in Small Business Loans: A Game-Theoretic Analysis of Evidence from PPP Loans in Durham, NC.”

44. Ran Duchin and others, “Concierge treatment from banks: Evidence from the paycheck protection program,” Journal of Corporate Finance 72 (2022): 102124, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2021.102124.

45. Timothy Bates and Alicia Robb, “Has the Community Reinvestment Act increased loan availability among small businesses operating in minority neighbourhoods?” Urban Studies 52 (9) (2015): 1702–1721.

46. Government Accountability Office, “Paycheck Protection Program: Program Changes Increased Lending to Smaller and Underserved Businesses” (2022), available at https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-22-105788.

47. Jack Northrup, Eric Hangen, and Michael Swack, “CDFIs and Online Business Lending: A Review of Recent Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities” (University of New Hampshire, 2016).

48. Erel and Liebersohn, “Does FinTech Substitute for Banks? Evidence from the Paycheck Protection Program.”

49. Rachel Atkins, Lisa Cook, and Robert Seamans, “Using Technology to Tackle Discrimination in Lending: The Role of Fintechs in the Paycheck Protection Program,” AEA Papers and Proceedings (112) (2022): 296–298.

50. Sabrina Howell and others, “Automation and Racial Disparities in Small Business Lending: Evidence from the Paycheck Protection Program.” Working Paper No. 29364 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021), available at https://doi.org/10.3386/w29364.

51. William D. Bradford, “The wealth dynamics of entrepreneurship for black and white families in the US,” Review of Income and Wealth 49 (1) (2003): 89–116; William D. Bradford, “The ‘myth’ that black entrepreneurship can reduce the gap in wealth between black and white families,” Economic Development Quarterly 28 (3) (2014): 254–269; C. Mirjam van Praag and Peter H. Versloot, “The economic benefits and costs of entrepreneurship: A review of the research,” Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship 4 (2) (2007): 65–154.

52. Diego F. Cuadros and others, “Dynamics of the COVID-19 epidemic in urban and rural areas in the United States,” Annals of Epidemiology 59 (2021): 16–20.

53. Gregorio A. Millett and others, “Assessing differential impacts of COVID-19 on black communities.”

54. Natalie Spievack and Megan Gallagher, “For Students of Color, Remote Learning Environments Pose Multiple Challenges” (Washington: Urban Institute, 2020), available at https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/students-color-remote-learning-environments-pose-multiple-challenges.