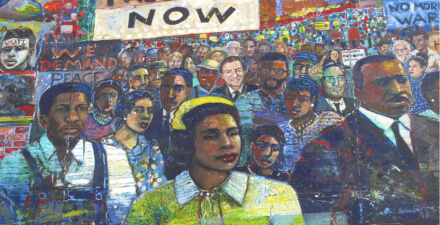

This year’s Juneteenth is a celebration of emancipation and a reminder that pervasive wealth inequality persists for most African Americans

Following nationwide protests across the United States in 2020 against police brutality, the push for federal recognition of Juneteenth gained momentum, with the U.S. Congress enacting legislation in the summer of 202l declaring June 19th a national holiday. The first anniversary of the federal holiday, celebrated on June 20 this year, is a moment for all Americans to honor the emancipation of enslaved African Americans following the end of the Civil War more than 150 years ago.

But Juneteenth also is an opportunity to take stock of congressional and state government efforts to account for the consequences of pervasive institutional racism before and after 1865 and evident still today. After all, the results of the brutal exploitation of enslaved African Americans to the systematic oppression in the Jim Crow South to today’s institutionalized racism are still evident in the disparate access to and outcomes in income, wealth, education, healthcare, jobs, housing, and criminal justice for so many Black workers and their families.

There is one initiative in Congress to establish a commission to study the effects of slavery and discriminatory policies on African Americans and recommend appropriate remedies, including reparations. Some cities and states are also working to address the need for reparations through piecemeal programs and initiatives. California’s Task Force to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans, for example, recently released its nearly 500-page report that says its findings have nationwide implications for the way the United States addresses reparations. And there are several more ways in which reparations could be handled by policymakers at the state and local levels.

Before examining those two reparations proposals, however, it’s first imperative to detail briefly why pervasive wealth inequality—the most telling consequence of the history, legacy, and enduring presence of systemic racism—persists for most African Americans. The reason: Over the course of U.S. history, the accumulation of wealth by the vast majority of generations of Africans Americans was categorically illegal (pre-1865) and then systemically and violently inhibited (post-1865) by Jim Crow laws, the exclusion of agricultural workers and domestic helpers from New Deal reforms, and sweeping housing-market redlining, among many other forms of institutional racism.

All of these barriers to opportunity to earn and save severely inhibited the accumulation of wealth in Black communities across generations. Indeed, government policy has created or maintained hurdles for African Americans who attempt to build, maintain, and pass on wealth. The share of wealth of African Americans is considerably lower than their percentage of the nation’s population, with Black Americans accounting for about 12 percent of the nation’s population but possessing only about 2.6 percent of the nation’s wealth.

This translates into a condition in which the average Black U.S. household has a net worth that is $800,000 lower than the average White household’s net worth. This wealth divide matters because it’s such a critical index of the cumulative effects across generations of racial injustice in the United States.

There are many people in the United States who consider the Civil Rights era of the 1960s as resolving the blatant racial discrimination in U.S. politics and society. Yet the post-Civil Rights period is marked to this day by housing discrimination, mass incarceration, and economic inequalities resulting from the intergenerational effects of White supremacy. What’s worse, calls for teaching this history and its legacy so that more Americans of all races and ethnicities understand the situation today are often met by political assaults from White Americans, particularly in the South, under the guise of combatting “critical race theory.”

This is another reason why reparations need to be on the table for discussion among economists and policymakers alike—documenting why reparations are called for is an important step in educating the broader U.S. public about the need for, as well as the benefits to, not just African Americans but the broader U.S. economy, too. Reparations, broadly understood, would be a program of “acknowledgment, redress, and closure.” It is not enough to merely recognize that Black Americans have suffered historical harm. There also must be steps taken to eliminate the effects of this harm.

Reparations would require the federal government to compensate for the effects of structural racism. The U.S. House of Representatives has a bill, H.R. 40, under consideration, with 196 co-sponsors and only 218 votes needed to pass. H.R. 40 would establish a 15-member commission to study the effects of slavery and discriminatory policies on African Americans and recommend appropriate remedies, including reparations.

More immediately, there is the already-completed study by California’s Task Force to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans. This recently released, nearly 500-page report has nationwide implications for the way the nation addresses the consequences of systemic racism, including a proposal for reparations. Indeed, highlights from the report are a must-read on this first anniversary of Juneteenth as a federal holiday.

The California task force hopes to complete its second stage of research on how to create a reparations program sometime in 2023. And perhaps by the end of the current 117th Congress, the U.S. House of Representatives will have passed legislation enabling a federal study and set of recommendations—though chances of full congressional enactment are unlikely.

Indeed, politics and the many legislative and administrative layers that come along with enacting and interpreting legislation more broadly continue to stand in the way of a reparations program at the state and federal level because expanding voter suppression laws are making it more and more difficult to build the political power to address race-based economic inequality.

That’s why the Juneteenth holiday—the historic and symbolic representation of African American’s liberation from institutionalized and legislative slavery and oppression—is so important to the nation’s future. While the historical legacy of Juneteenth shows the value of never giving up hope in uncertain times, the day should also remind the nation that even decades later, we still have work to do.