Austerity policies in the United States caused ‘stagflation’ in the 1970s and would do so again today

In the current debate among economists and policymakers in the United States about the causes of inflation, one of the most persistent and most deeply rooted questions is whether today’s round of price increases are, fundamentally “macroeconomic” in scope—meaning they are happening because there is a general excess of demand over supply. Despite findings from both journalists and the White House that swelling industry profits and bottlenecks in the industries supplying pandemic-shaped demand are the main forces behind recent price increase, there is remarkable insistence from senior officials in both political parties that general fiscal restraint should be the stabilization instrument of choice.

“Ultimately inflation is a macroeconomic problem,” writes Jason Furman, the former head of President Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, in The Wall Street Journal. He attributes rising prices to the “oversize and poorly designed” coronavirus recession rescue packages of December 2020 and March 2021. In The Washington Post, former Clinton administration U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers describes the present moment as one of an “overheating economy” caused by “far too much fiscal stimulus and overly easy monetary policy.”

Sen. Pat Toomey (R-PA), the ranking member of the Senate Banking Committee, echoes this interpretation. “Congressional Democrats’ extreme Leftist policies are contributing to the price hikes hitting Americans’ wallets,” he said in late November. Democrats, he continued, are “pushing a multi-trillion dollar reckless tax-and-spend plan that will contribute to more inflation and damage our economy.”

Across the ideological spectrum, influential voices today echo the complaint heard during the Cold War most frequently among Southern Democrats, Midwest small business leaders, and Western insurgents of the Republican Party: Sustained non-defense-related government spending and low interest rates increase inflationary pressures, in turn destabilizing the U.S. economy and society. As the late Arizona Senator and Republican Party presidential candidate Barry Goldwater complained during the late 1960s, “the essential item in the inflation we are experiencing is government spending.” Preparing his California gubernatorial campaign stump speech in 1966, Hollywood actor Ronald Reagan said the same: “The real cause of inflation is government spending.”

To the extent this conventional wisdom about inflation is rooted in historical knowledge, it is the latent memory of this conservative diagnosis of the previous serious bout of inflation, which began with the escalation of the Vietnam War in 1965 and extended through the two import-driven oil-price spikes in 1974 and 1979. This view holds that the prolonged period of rising prices in the 1960s and 1970s was fundamentally an error in the “indirect” macroeconomic management of fiscal and monetary policy, meaning there was too much government spending and borrowing costs that were too low due to lax monetary policy.

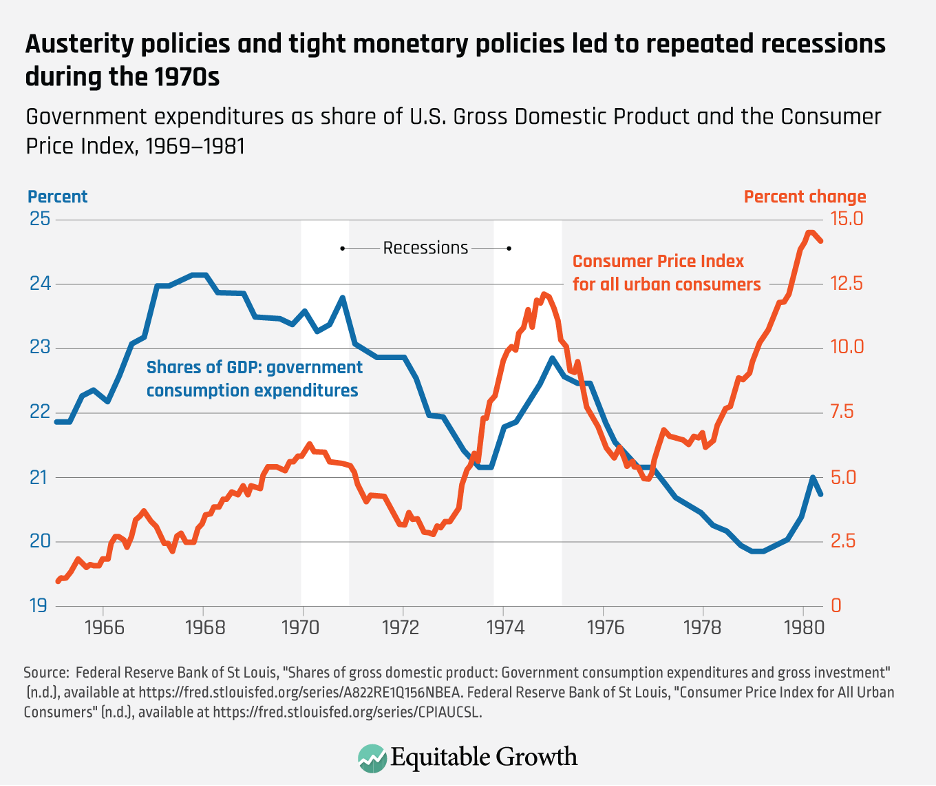

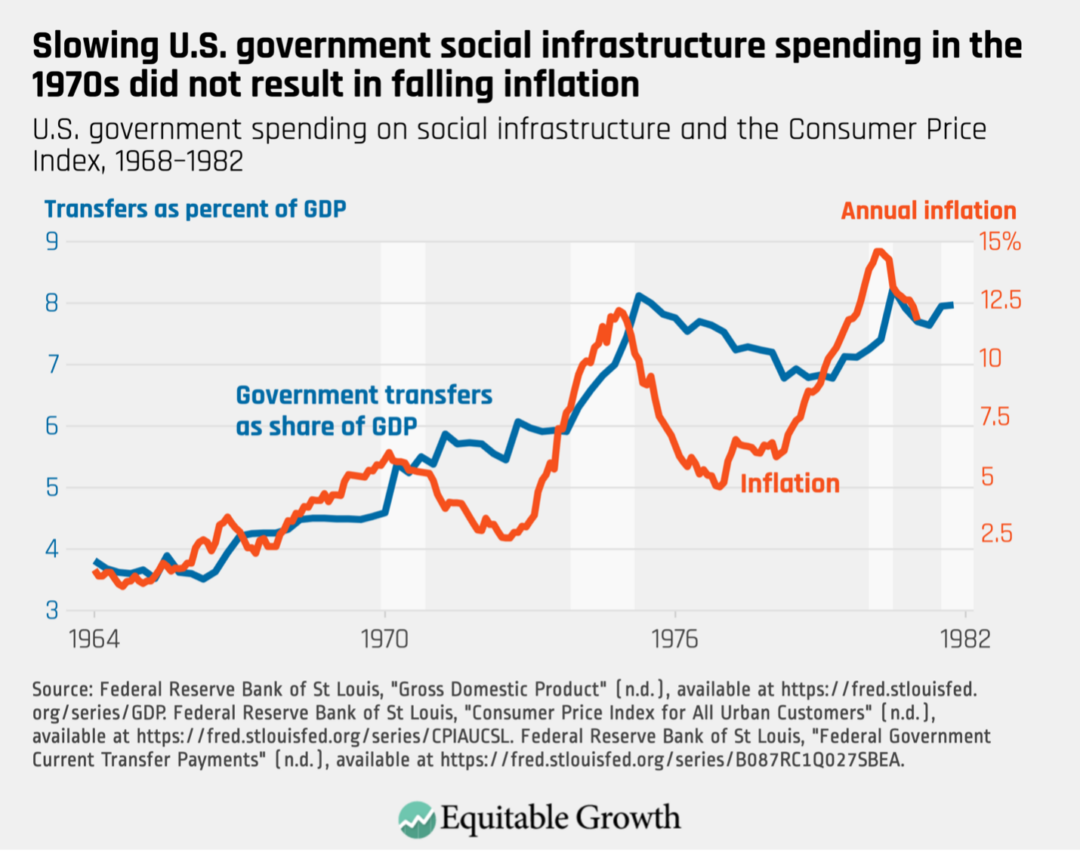

This interpretation was wrongheaded then—see Figure 1—and it is wrong now.

Figure 1

First of all, it is historically and economically wrong that the previous round of sustained inflation was driven by Congress spending uncontrollably on “social programs”—nondefense expenditures and government transfers such as food stamps, the Aid to Families with Dependent Children program, and the Medicare and Medicaid programs. In fact, austerity measures taken to varying degrees by the Nixon, Ford, and Carter administrations coincided with accelerating price increases. Indeed, during the 1970s, small increases in what we would today call “social infrastructure” spending were actually associated with the subsiding of inflation.

Secondly, there is good evidence that the microeconomic and macroeconomic management tools used by the Kennedy and Johnson administrations in the 1960s to stem price increases—a surgical and largely voluntary attempt to encourage certain industries to follow wage and price guidelines, per the direction set by fiscal policy—were working to a large degree, according to the late economist Arthur Okun as detailed in his 1970 book, The Political Economy of Prosperity. It wasn’t until the Nixon administration eschewed these tactics that the U.S. economy experienced real price escalation—an inflationary spiral that continued under the Ford and Carter administrations due to their own misplaced reliance on fiscal austerity, exacerbated by two sharp import-driven energy price spikes.

Combined, these historical and economic facts provide an important lesson to today’s policymakers. Namely, fiscal austerity is not an antidote to today’s inflation. Instead, austerity will likely exacerbate aggressive wage hikes and profit taking, and the inflation that can produce.

This column will walk through this history to demonstrate why the lessons mislearned in the 1970s about austerity policies, if repeated now, could well result in the same inflationary spiral and economic volatility that marked that era in U.S. economic history.

The history of fiscal austerity and monetary restraint as anti-inflation tools

It was the misguided belief that the inflation of the 1970s was, at root, a macroeconomic problem that led the Nixon, Ford, and Carter administrations to restrain government spending. Each of these administrations leaned toward fiscal and monetary contraction to slow rising prices—but it did not work. Fiscal contraction only exacerbated a decade of high unemployment by inducing three recessions and prolonging business uncertainty, while discretionary monetary policy drove wild swings in construction, antagonizing building contractors, homeowners, and workers across the nation. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

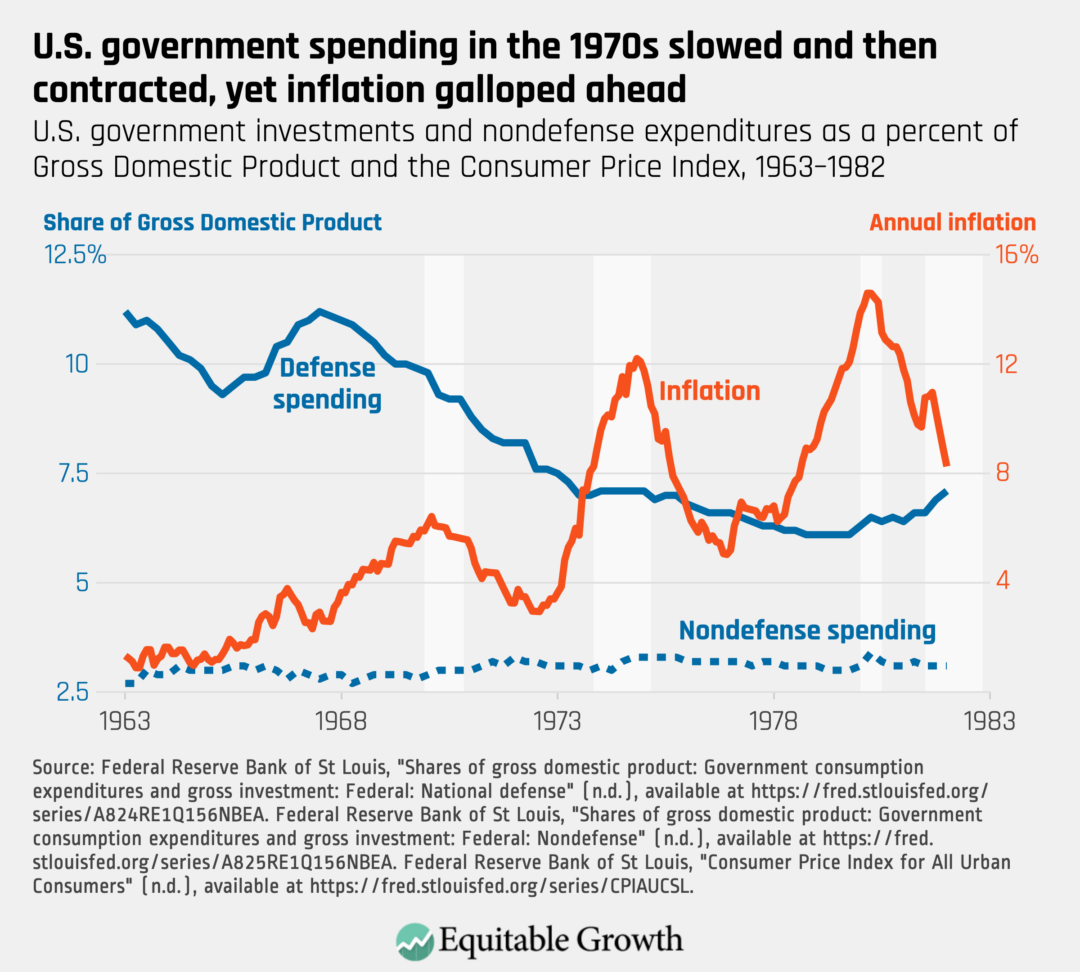

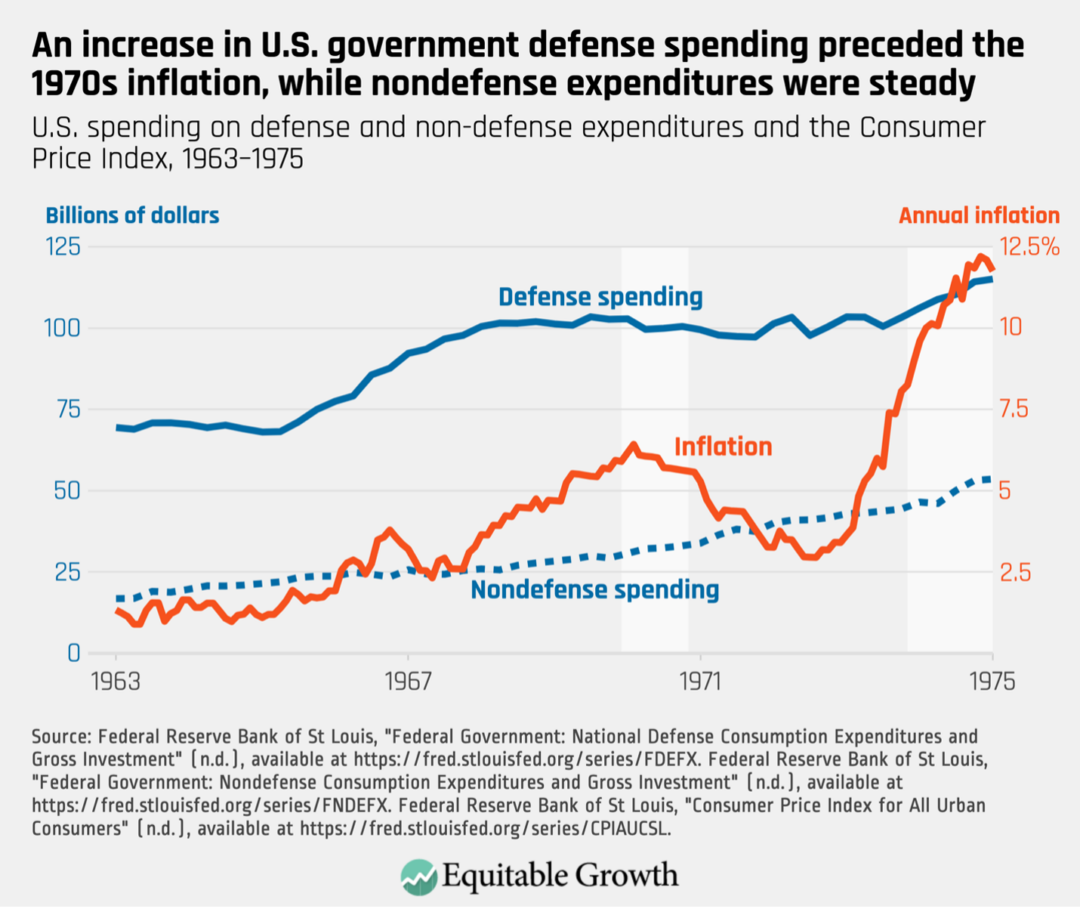

It is important to emphasize that the federal government’s share of Gross Domestic Product declined persistently throughout the inflationary years of the 1970s. While the defense share of GDP drove the overall decline in the federal share—due to the end of the Vietnam War and détente with the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China—this is even true when considering only nondefense expenditures and transfers, which fiscal hawks then, as now, invariably target for criticism rather than defense spending. Indeed, the nondefense share of GDP fluctuated very little during the 1970s. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

It was these fiscal austerity drives that created the “stag” in stagflation. This was deliberate policy—and recognized as such at the time. After the 1972 elections, for example, the Nixon administration put an economy-breaking ceiling on federal expenditures, which the Ford administration tried to continue until the 1974 recession forced up unemployment claims.

This was the original “sequestration” move by fiscal-policy hawks—the 1973 “impoundment” of congressionally appropriated funds that the Nixon White House used to starve public institutions across the U.S. economy, long before the 113th U.S. Congress in 2013, led by then-Speaker of the House Paul Ryan (R-WI). Of course, threats by fiscal hawks to shut down the U.S. government to curtail federal spending have been regular features of U.S. politics since the 1990s, as the general decline in the federal tax-revenue share of GDP coincided with skyrocketing U.S. income and wealth inequality.

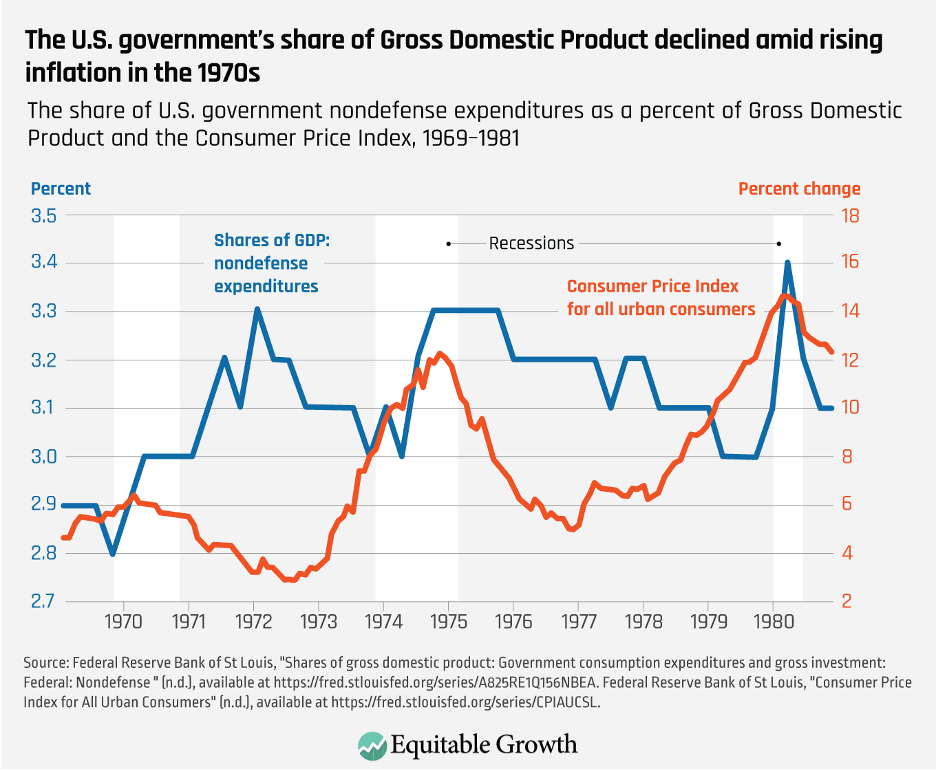

There was no dramatic and sudden increase in federal social infrastructure spending during the 1970s. The increases in the so-called transfer-payment share of GDP that did occur were only during recessions. Opportunistically, many politicians and conservative intellectuals defined the decade’s political culture through misplaced and often racist popular caricatures of “welfare queens” and the “undeserving” unemployed collecting public Unemployment Insurance. Yet across the decade, the growth of transfers was moderate and gradual, and intentionally slowed to keep pace with the growth of the private sector. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

So, what caused stagflation in the 1970s?

It’s clear that fiscal macroeconomic restraint did not cure inflation during the 1970s. But what caused the steady rise in prices? Most historians agree with contemporary journalistic accounts that the inflation grew out of President Lyndon Johnson’s decision to escalate the Vietnam War in July 1965 without moving the U.S. economy to a “war footing”—by not instituting excess-profits taxes, wage-price controls, or, at the very least, a wartime income-tax increase to accompany the war. The only “bump” in federal expenditures during the previous period of inflation occurred in defense spending. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

Less understood is the burst of price and wage increases in 1969 and 1970, when the Nixon administration entered office and renounced the Kennedy and Johnson administrations’ program of shaping production in key markets and planning wage-price guidelines. These efforts by the two Democratic administrations in effect maintained progressive fiscal policies to sustain high employment and expand social infrastructure programs. In exchange, the largest unions of the AFL-CIO agreed to moderate wage demands.

Likewise, the Kennedy and Johnson administrations encouraged the largest and most efficient companies capable of influencing product and services prices in their markets to pass on productivity increases in the form of lower prices and higher capacity utilization, rather than taking them as monopolistic profits.

When Marilyn Monroe sang “Happy Birthday, Mr. President” to John F. Kennedy in May 1962, her lyrics actually sang the praises of enforcing price guidelines in the steel industry:

For all the things you’ve done/ The battles that you’ve won/ The way you deal with U.S. Steel/ And our problems by the ton/ We thank you so much.

The incoming Nixon administration campaigned against this principle. Under the flag of “free enterprise” guided by hands-off government macroeconomic policies, the White House ended all microeconomic interventions, such as wage and price guidelines and exhortations. In the process, the 3 percent rate of inflation under President Johnson became a 6 percent rate of inflation under President Richard Nixon.

When the Nixon administration, in August 1971, did stabilize the economy after the 1970 recession—by tellingly using a formal wage-price freeze and phased price-control program—it paired its “incomes policy” with an acceleration of government spending timed to a climax in November to December 1972—the moment of presidential election. Incomes policy broadly refers to the kind of social compacts forged by governments, the private sector, and labor unions in Western Europe at the time to tame inflation without inducing a recession.

This history is often written as if such planning efforts were pursued in lieu of macroeconomic fiscal-monetary guidance, but nothing could be further from the truth. They were always described by their administrators as “supplementary” and temporary—and, if anything, it is this reticence to engage in incomes policies that explains their historical weakness in the United States. What’s more, the inflation that exploded during 1973—for 10 months before the first foreign oil shock—resulted from their immediate repeal and the shifting of the stabilization program to a purely macroeconomic basis.

In the moment of political victory in January 1973, the Nixon administration rejected its temporary incomes policy and turned dramatically toward austerity, defunding what remained of the Johnson-era Office of Economic Opportunity, the core office responsible for administering the War on Poverty programs, and imposing a ceiling on congressional appropriations. The result was an explosion of prices, as U.S. corporations rebuilt profit margins squeezed by the 16 months of government price regulations.

Then, after 10 months of this unstable domestic situation, the first “oil shock” slammed the U.S. economy. Orchestrated by the ambitious and suddenly powerful Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, or OPEC, the price hike came in opposition to U.S. foreign policy—specifically, in response to the October 1973 Yom-Kippur War between Israel, Egypt, and Syria. Inflation, for the first time, entered double-digit territory by 1975.

To be sure, there were real policy errors that allowed this runaway bout of inflation to happen—but they were microeconomic as much as macroeconomic errors. Just when austerity was imposed to reduce demand, the Nixon administration released controls over profit margins and allowed producers to recoup revenues in price increases. By freeing the corporate sector to drive up prices swiftly and sharply before supply had caught up to the administration’s election-year demand, the Nixon White House produced double-digit inflation.

But in neither 1972 nor in 2021 would it be reasonable to argue that the U.S. economy was experiencing a general excess of demand. Unemployment at the time persisted in many cities then, as now, demonstrating that the existing level and composition of demand was inadequate for achieving full employment. The composition of demand in both situations included enough bottleneck sectors to drive rising prices—famously, wheat and corn prices after the 1972 détente grain deals with the Soviet Union, as well as petroleum and steel prices.

Some of these sudden price spikes resulted from inadequate forward planning. Then-White House adviser Donald Rumsfeld and U.S. Department of Agriculture Secretary Earl Butz rejected the pleas of the Cost-of-Living Council to expand planned acreage for 1972 and 1973, before and after the rush of purchases by the Soviet Union. Other spikes, such as petroleum, were rooted in deeper geopolitical shifts driving the terms of trade with the developing world. Amid these sector-specific price increases, fiscal-monetary restraint exacerbated wide areas of unemployment, particularly in many cities and among people of color—as our memory of the era’s “urban crisis” attests.

Yet the misinterpretation of the inflationary pressures in the 1970s persists today. As Harvard’s Summers has written elsewhere about this era, “The first attempts to contain inflation were too timid to be effective, and success was achieved only with highly determined policy. A crucial step was the abandonment of the idea that the problem was structural in nature rather than driven by macroeconomic policy.” Summers is wrong. The mistakes made in the 1970s were precisely the limitations placed on the expansionary fiscal and monetary policies required for effective sectoral planning.

Lessons to be learned from the causes of stagflation in the 1970s

The persistence of the misinterpretation of inflationary pressures in the 1970s is worth considering today. In the period since the 1970s, the macroeconomic prescription for inflation has been to induce a recession that is long and deep enough to stop prices from rising. To work, proponents of this macro-only approach argue, the policy must be well-telegraphed to the public, unwavering in its implementation, and, until only recently, free of any microeconomic policies that might distract from the imperative of fiscal-monetary restraint.

This is different than the contending claims of price controllers then, and of experts today urging more extensive planning. From their perspectives, inflation persists because incomes policies—rather than the induced recessions of 1970 and 1974—were not given enough time to work. Rising prices are, after all, a traditionally business-friendly incentive to expand production and capacity. If supply is to increase without higher prices, then the simplest alternative is to produce for the market at a loss, offset by subsidies from the public budget. But this can subject producers’ incomes to public supervision, and that didn’t happen during the late 1970s.

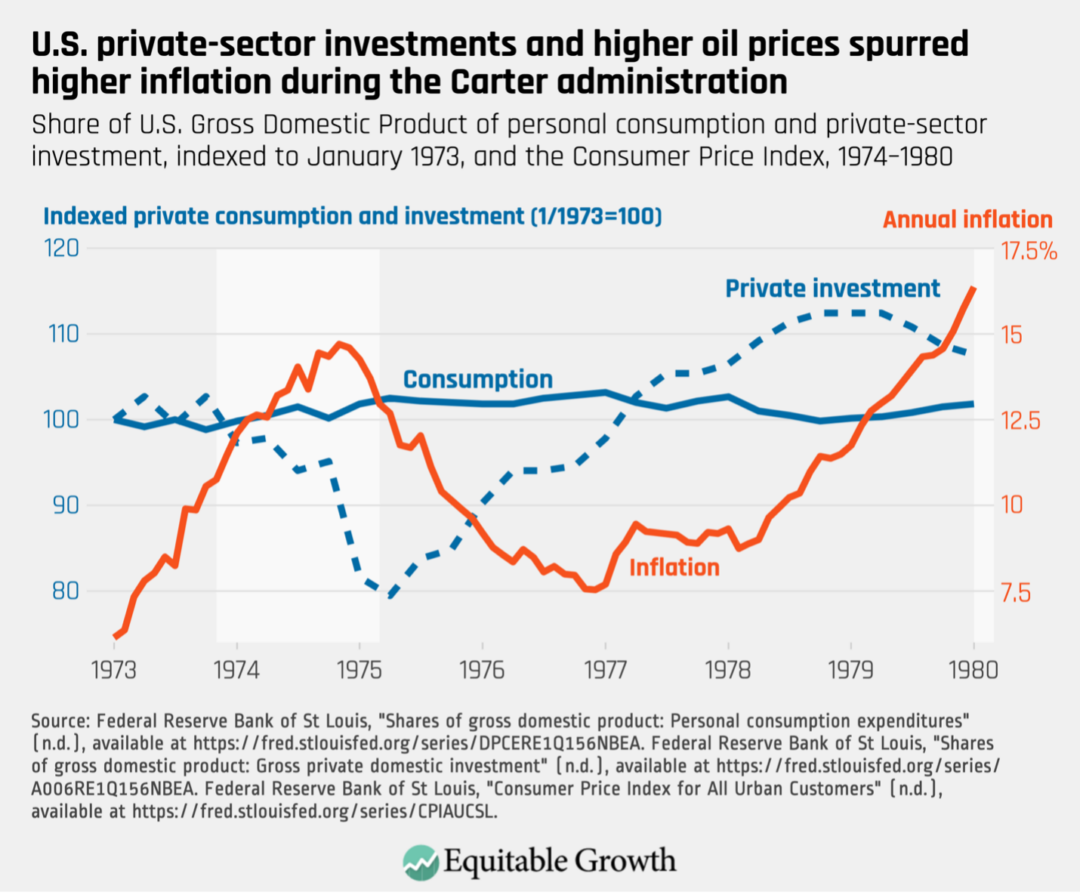

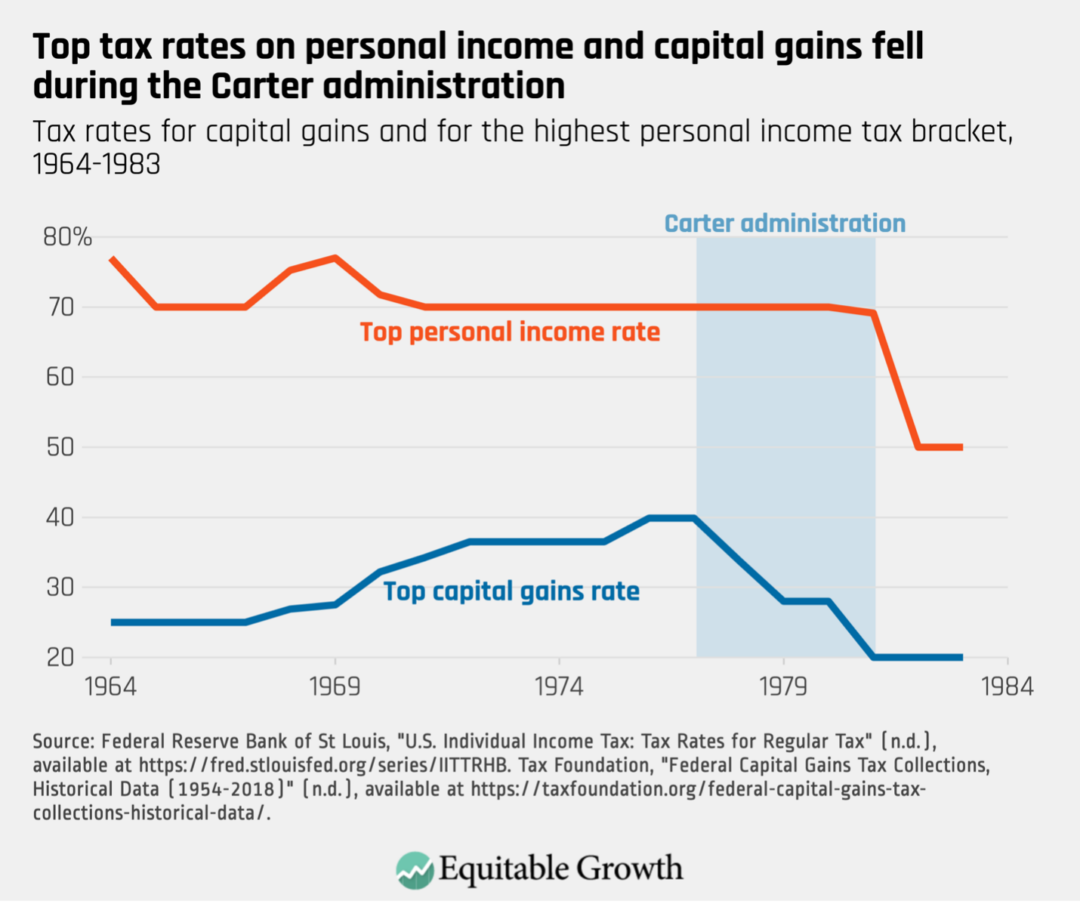

When President Gerald Ford’s austerity policies failed to stabilize the U.S. economy, the Carter administration sought to manage a rapid recovery through a private-sector growth program. To induce private investment and expand capacity, this program relied on the incentives of private corporate earnings through unregulated profits and tax cuts—in particular, a capital gains tax cut in 1978. Amid inherited cost increases, this private-investment and profit boom came at the expense of personal consumption in the form of even higher inflation. Between 1977 and 1979, as the gross private investment share of GDP increased from 18 percent to 21 percent, personal consumption in the economy actually fell. (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6

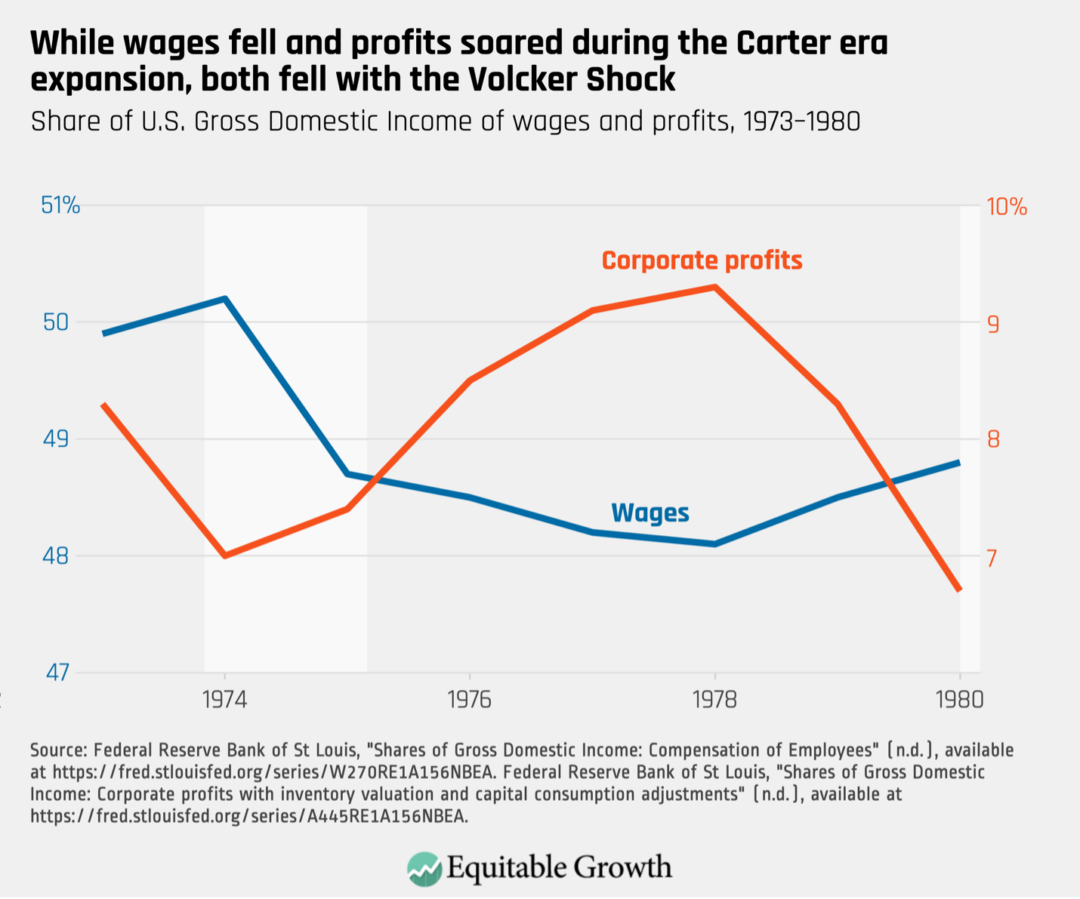

As a share of national income, wages and salaries fell steadily in the 1970s. The surge in private investment accelerated the development of the Gulf Coast petroleum industry and financed a wave of construction across the Sunbelt. But the resulting business boom itself pushed up the general price level, with neither personal consumption expenditures nor the federal-spending share of GDP rising during the Carter years.

In fact, if any correlation between nondefense spending and price levels can be drawn from the 1970s, it is that inflation subsided when nondefense spending expanded, as detailed in Figures 2 and 3 above.

This makes sense when one considers the institutional factors bearing on the determination of wages. When workers’ consumption of basic services is stabilized by public programs, they have less incentive to seek to squeeze it out of their profit-seeking employers, particularly if existing wage differentials are perceived to be equitable. Such perceptions of equity were rare during the 1970s, but there is likewise little evidence that any aggressive union wage offensive drove the decade’s inflation.

In fact, that decade’s upsurge in labor militancy and strike action was purely defensive, as workers sought—with decreasing effectiveness—to defend their real incomes amid the supply-shortage and profit-driven inflation, particularly during the Carter administration era’s economic expansion. (See Figure 7.)

Figure 7

Before the so-called Volcker Shock began in 1979, the incomes policies that sought to stabilize and to direct shares of the U.S. economy were the cutting edge of macroeconomic policy discussion. During both World War II and the Korean War, subsidies to producers selling under controlled prices performed an economically analogous function of coordinating the growth of money incomes to the limits of real output. But whereas the Truman, Kennedy, and Johnson administrations had been willing to move toward this direction by managing wages and prices, and while even the Nixon administration opportunistically used this playbook, the Carter administration did not. Instead, the Carter administration’s growth program relied on the incentives of private corporate earnings to induce investment and expand capacity. (See Figure 8.)

Figure 8

Conclusion

If the U.S. economy today cannot sustain expanded public investments in physical and social infrastructure or support higher incomes for working people, then the appropriate response to today’s inflation may well be to bring demand down to the lower levels of pandemic-restricted supply. This option, of course, is neither politically feasible nor economically responsible.

But there is evidence that public investments can tame current price pressures, not least because of the experience of the late 1960s, the early 1950s, and, of course, during World War II. Advocates of fiscal restraint today may consider a national U-3 unemployment rate (defined as unemployed people actively looking for work) of 4.2 percent as a sign there are too many jobs and too few workers to fill them, risking a runaway inflation. But the economywide rate of capacity utilization (the key measure of U.S. economic capacity) is still well-below its pre-pandemic level.

According to the Federal Reserve’s survey of production and capacity, utilization has measured around 76 percent since the summer of 2021, compared to 79 percent and 80 percent in the low-inflation years of 2014 and 2018. In November, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported the U-3 unemployment measure much higher than the national average, from 5.1 percent in Chicago and 5.4 percent in Houston to 6.3 percent in New York City and 7.1 percent in Los Angeles.

The value of racial and gender diversity at the Federal Reserve

September 16, 2021

The economic evidence behind 10 policies in the Build Back Better Act

November 24, 2021

Then, there’s the fuller U-6 unemployment measure, which includes those working part time for economic reasons. It remains at a staggering 7.8 percent nationally. The U.S. labor market, in short, is nowhere near maximum employment.

The upshot: The production of goods and services in the U.S. economy can expand because there is excess capacity and underemployment. It is not shortages that are driving up prices in every market—though in select bottlenecks, there are capacity constraints that can and do ripple out through the supply chain. Rather, it is the general increase in producer profits and wages that is taking place as corporations take advantage of what many see as a temporary condition of government stimulus and workers seek to rectify perceived historical wrongs.

The answer, then, is for U.S. government fiscal policies to continue to support physical and social infrastructure spending amid the continuing coronavirus pandemic. These policies will sustain a high level of demand in the U.S. economy to encourage market forces and should be complemented by plans to prepare where markets fail. For those who believe the nation can supply the changing demands of a more egalitarian society, maintaining a high level of government spending is an indispensable condition.

But should the notion persist that inflation is essentially a macroeconomic problem that warrants the macroeconomic solution of reduced spending through raising interest rates and curtailing public budgets, then that needed demand will not be available for producers to meet. Without it, the vision of remaking the U.S. economy will go nowhere, economically or politically.

— Andrew Elrod holds a Ph.D. in history from the University of California, Santa Barbara and is a 2016 Washington Center for Equitable Growth grantee. Elrod, in the fall of 2021, completed his dissertation on the history of wage and price controls in the United States between 1940 and 1980. He works in the research department at UTLA, a 36,000-member public-sector labor union in Los Angeles.