Competitive Edge: Big Ag’s monopsony problem: How market dominance harms U.S. workers and consumers

Antitrust and competition issues are receiving renewed interest, and for good reason. So far, the discussion has occurred at a high level of generality. To address important specific antitrust enforcement and competition issues, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth has launched this blog, which we call “Competitive Edge.” This series features leading experts in antitrust enforcement on a broad range of topics: potential areas for antitrust enforcement, concerns about existing doctrine, practical realities enforcers face, proposals for reform, and broader policies to promote competition. Hiba Hafiz and Nathan Miller authored this contribution.

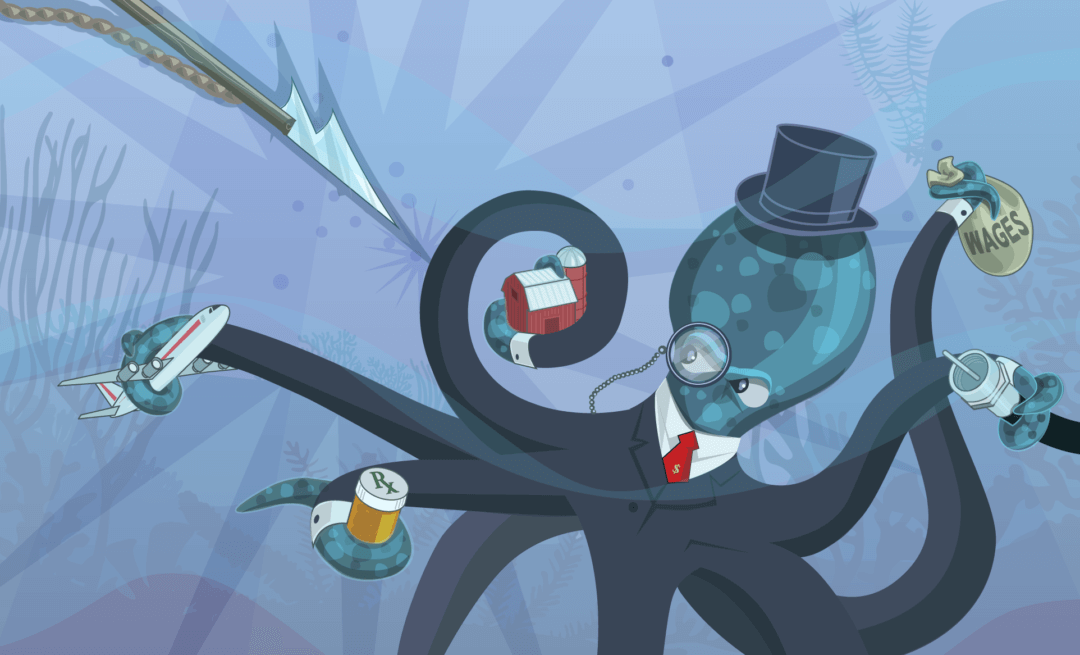

The octopus image, above, updates an iconic editorial cartoon first published in 1904 in the magazine Puck to portray the Standard Oil monopoly. Please note the harpoon. Our goal for Competitive Edge is to promote the development of sharp and effective tools to increase competition in the United States economy.

Agricultural markets are among the most highly concentrated in the United States. The markets for beef, pork, and poultry, grain, seeds, and pesticides are dominated by four firms. Three firms dominate the biotechnology industry. One or at best two firms control large farm equipment manufacturing. And a small number of firms are increasingly dominating agricultural data and information markets.

Yet former Iowa Gov. Tom Vilsack (D)—President Joe Biden’s nominee for secretary of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the same position Gov. Vilsack held during the Obama administration—has come out against breaking up Big Ag firms. “There are a substantial number of people hired and employed by those businesses,” he said last year. “You’re essentially saying to those folks, ‘You might be out of a job.’ That to me is not a winning message.”

Gov. Vilsack couldn’t be more wrong on the economics. It is precisely Big Ag’s buyer power in agricultural markets—these firms’ “monopsony” power—that destroys jobs and suppresses small farmer and worker pay.

Economic theory describes monopsony power as market power on the buy side of the market—it’s the analogue of monopoly power on the sell side of the market. Artificially acquiring or maintaining market power is unlawful under the U.S. antitrust laws, regardless of whether it derives from the buy or sell side. And that’s because buy-side power can be just as socially harmful as sell-side power.

Firms insulated from competition in input markets can profitably suppress the pay to suppliers of goods, services, and labor below the value that those suppliers provide. And lower pay has broader economic outcomes. It means suppliers have weaker incentives to provide the same quantity of inputs or invest in capacity, innovation, and quality. So, monopsony power can decrease input suppliers’ pay and the quantity of inputs buyers purchase.

Monopsony power can also harm downstream consumers. Less input means less output, and less output means more scarcity and higher prices to downstream consumers than would otherwise exist under competitive conditions.1

Taking steps to mitigate buyer power through aggressive antitrust enforcement and appropriate regulation can be a win-win for input suppliers and downstream consumers. Competition among buyers helps ensure that suppliers are paid according to their value. And competition increases output incentives and ultimately lowers downstream prices as well.

The monopsony power of Big Ag poultry, pork, and meat companies

The buyer power of companies such as Tyson Foods Corporation, Cargill PLC, and Smithfield Foods Inc. comes from high levels of market concentration in the agricultural industry. Simply put: Big Ag faces too little competition when they hire workers or procure inputs such as chicken (Tyson), hogs (Smithfield), or cattle (Cargill) from smaller suppliers.

Top Big Ag firms have merged with and acquired smaller firms in the industry over the past five decades, increasing consolidation of livestock packers, beef processors, and poultry processors. According to a recent agricultural industry report by the Center for American Progress, between 1986 and 2008, “the four-firm share of animal slaughter nationwide increased from 55 percent to 79 percent for cattle, from 33 percent to 65 percent for hogs, and from 34 percent to 57 percent for poultry.” High market concentration increased Big Ag’s price- and wage-setting power over cattle producers, hog and poultry farmers, and meat processing plant workers, lowering their prices for hogs, beef, chickens, and labor.

Big Ag’s concentration numbers at the local level are even more stark than at the national level. Most buying and processing of poultry, hogs, and beef happens locally to avoid high transportation and storage costs. Big Ag dominates local markets as the only buyers in town. More than 20 percent of poultry growers have only one local upstream buyer for poultry and 30 percent have only two.

Most hog growers face packer monopsony at the local level, with just one or two packers offering them contracts. One telling case in point: After dominant meat processor JBS S.A. acquired Cargill’s pork processing operations in 2015, the American Antitrust Institute and a coalition of farmers’ unions projected that only two firms—Tyson and the merged JBS-Cargill pork processing unit—would buy and slaughter 82 percent of hogs in Illinois, Indiana, and surrounding states. Similarly, local cash markets for cattle typically feature no more than three or four packers.

Concentration at the local level means that Big Ag can artificially suppress pay to cattle producers, hog and poultry farmers, and processing plant workers below the value that their inputs provide to the industry.

Evidence of the effects of Big Ag poultry, pork, and beef companies’ monopsony power

Empirical evidence of the effects of Big Ag’s buyer power on rural communities and consumers nationally is mounting. Suppliers and processing workers suffer lower pay while downstream consumers are paying higher prices on essential food. Around “three-quarters of contract growers live below the poverty line,” and average-sized operators lose money 2 out of 3 years.

Then, there is the evidence of rising farm bankruptcy rates. Farm bankruptcies have steadily increased every year for the past decade, due, in part, to high U.S. farm debt. Small farmers are not the only ones being undercompensated—a 2000 U.S. Department of Labor survey found that 100 percent of poultry processing plants failed to comply with federal wage-and-hour laws.

Buyer power also enables processors to impose abominable working conditions without workers quitting. Even before the coronavirus pandemic, poultry processing workers suffered occupational illnesses at five times the rate of other U.S. workers. But their conditions plummeted during the pandemic, with immigrant workers and workers of color suffering the most. A November 2020 study estimated livestock processing plants suffered 236,000 to 310,000 cases of COVID-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus, and 4,300 to 5,200 deaths—3 percent to 4 percent of all U.S. deaths—with the majority related to community spread. Consumers have also suffer nationally by having to pay higher prices for meat products while facing fewer choices and lower quality.

More evidence of Big Ag’s buyer power emerges from high-profile U.S. Department of Justice and private enforcement actions against dominant Big Ag buyers in the poultry and pork industries for colluding to fix prices, rig bids, and suppress pay to growers and processing workers. High concentration levels make it easier for Big Ag firms to collude, and in June 2020, the Department of Justice indicted leading chicken industry defendants for price-fixing and bid-rigging in the broiler chicken market. Civil suits were filed against Tyson, Pilgrim’s Pride Corp., and others for price-fixing, wage-fixing, and using no-poach agreements in the markets for broiler chicken products, contract farmer services (contract farmers are farmers who grow chickens from chicks to market weight in long-term contracts with processors), and chicken-processing labor services.

The Department of Justice is currently investigating price-fixing and bid-rigging among dominant beef processors, too, and private plaintiffs have sued pork and beef processors for allegedly colluding to lower prices paid to producers and raise prices for consumers. Current litigation against the poultry, pork, and meat cartels estimates that hundreds of thousands of workers suffer poverty wages from wage-fixing conspiracies.

Big Ag is able to exercise its buyer power through its industry-transforming supply chain restructuring that allows lead firms to extract rents at each layer of their supply chain for their profit, and most especially, from small farmers and workers at the production level.2 Starting in the 1960s, poultry firms such as Tyson vertically integrated to own or control hatcheries, feed mills, veterinary care, slaughterhouses, processors, and sales contracts with poultry growers. The pork industry followed Tyson’s lead in the early 1980s, extending top-down ownership or control of hog production, packing, and processing in large-scale farms and processing facilities.

The only level of the supply chain not directly owned or operated by Big Ag chicken and pork producers is the growing stage, where Big Ag processors rely on small farmers to grow and raise the broilers and hogs provided by Big Ag-provided breeders, hatcheries, farrows, and weaners to slaughter weight. Still, Big Ag firms in these two meat sectors can squeeze these growers’ margins from above andbelow: Their inputs are supplied by Big Ag, and their product is sold to Big Ag.

Big Ag does this through contractual controls, forcing growers into one-sided production and marketing contracts while using their significant control over spot or cash markets to limit sales outside those contracts. Around 97 percent of chicken broilers are raised by contract growers in “take it or leave it” contractual arrangements; 63 percent of hogs were contractually raised in 2017, nearly double that in 1997.

These arrangements are crippling. Chicken growers’ production contracts require significant sunk investments—around $1 million in mostly debt-financing—and growers are required to purchase nearly all inputs, veterinary care, and technical assistance from vertically integrated buyers. Buyers can change or terminate contracts for almost any reason. Farmers sell their chickens in a “tournament system,” where their chickens compete for rankings with others given the same feed amount, but the ranking process lacks transparency—buyers weigh chickens behind closed doors and provide no standards for knowing whether a farmer is “getting the same inputs as the other farmers against whom the company makes him compete,” according to Lina Khan, then-policy analyst at the New America Foundation and now an assistant professor of law at Columbia Law School.

Big Ag buyers can retaliate against resistant farmers by refusing to renew contracts or sending bad feed or unhealthy chicks in future seasons—a system likened to “indentured servitude” by former chicken farmers suing Big Ag poultry firms. Contracts for hog growers also require significant capital investments, place much of the liability and risk for raising hogs on growers, and subject growers to unilateral buyer compensation-setting with limited transparency, and similarly allow retaliation through threats of contract termination or future substandard livestock or feed supply.

The beef industry is less vertically integrated than chicken and poultry. Beef packers find vertical supply chain ownership less profitable, yet these packers have achieved a degree of de facto control over the thousands of independent feedlots that supply them. Since the 1980s, and following meatpacker consolidation into the Big Four—Cargill, JBS, National Beef Inc., and Tyson Foods—the number of packing plants nationwide dropped 81 percent, and nearly a third of all the feedlots that purchase cattle from ranchers for fattening and resale to meatpackers have left the industry.

Among the feedlots that remain, most sign long-term contracts with the Big Four. More than 75 percent of packer cattle purchases come from long-term contracts with feedlots, up from 34 percent in 2004. Because most contract prices are pegged to outcomes in a subsequent cash market, this weakens packers’ incentives to bid aggressively in that cash market—bidding aggressively would just increase their payments for cattle already under contract.

So, in addition to alleged collusion among the Big Four beef packers to lower feeder pay—estimated at an average of 7.9 percent below average pay since 2015—feeders are also squeezed by the Big Four’s network of contracts and bidding schemes that the packers can profitably impose upstream.

Conclusion: Anti-monopsony action is urgently needed to protect workers and consumers

The economic theory is clear, and mounting empirical evidence backs it up: Big Ag’s monopsony power leads to fewer jobs, lower wages, and worse conditions dominating our nation’s food supply. And local farming communities are hurting. If U.S. Agriculture Secretary-nominee Vilsack wants to help rural communities—and reduce food prices for consumers in the bargain—he must get the economics right.

President Biden committed to strengthening antitrust enforcement to “help family farms and other small- and medium-sized farms thrive.” Before confirming Gov. Vilsack, Democratic senators must secure his public commitment to aggressively enforcing the Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921 and partnering with the U.S. Department of Justice to take on Big Ag’s buyer power. If keeping good jobs and sustainable business in rural America is the incoming administration’s priority, they can’t leave small farmers and workers to face Big Ag alone.

—Hiba Hafiz is an assistant professor of law at Boston College Law School. Nathan Miller is the Saleh Romeih associate professor at the Georgetown University McDonough School of Business.

End Notes

1. It is possible for a firm to have monopsony power upstream but face competition in downstream markets in conditions that resemble perfect competition (no product differentiation and populated by many small firms with low market share). See, for example,C. Scott Hemphill and Nancy Rose, “Mergers that Harm Sellers” Yale Law Journal 127 (7) (2019). But those conditions are rare in reality, as economists recognize. See, for example, Roger G. Noll, “‘Buyer Power’ and Economic Policy,” Antitrust Law Journal 72 (2) (2005), arguing that, “because output of the monopsonized good is less than the social optimum and other inputs are not perfect substitutes for this input, final goods will be under-supplied as well, causing real final goods prices to be higher than would be the case in the absence of monopsony …. Although some have claimed otherwise, these fundamental results about the effects of single-price monopsony do not depend on either the extent of competition or the cost structure of other firms in the downstream market.” See also Peter C. Carstensen, “Buyer Cartels v. Buyer Groups,” William & Mary Business Law Review 1 (1) (2010); Roger D. Blair and Jeffrey L. Harrison, “Antitrust Policy and Monopsony,” Cornell Law Review 76 (2) (1991); John B. Kirkwood, “Powerful Buyers and Merger Enforcement,” Boston University Law Review 92 (4) (2012).

2. Vertical integration can create real efficiencies by streamlining production and distribution that can make supply purchasing more predictable for all parties, including small farmers. But it also raises barriers to entry. Vertical integration makes it difficult, for example, for a firm engaged in chicken processing to earn a profit without also building a vertically integrated complex of breeder flocks, hatcheries, and feed mills. Forcing firms to enter two or more additional levels of the supply chain in order to be profitable deters entry and entrenches Big Ag monopsony.