Weekend reading: Voter suppression and economic inequality in the United States edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

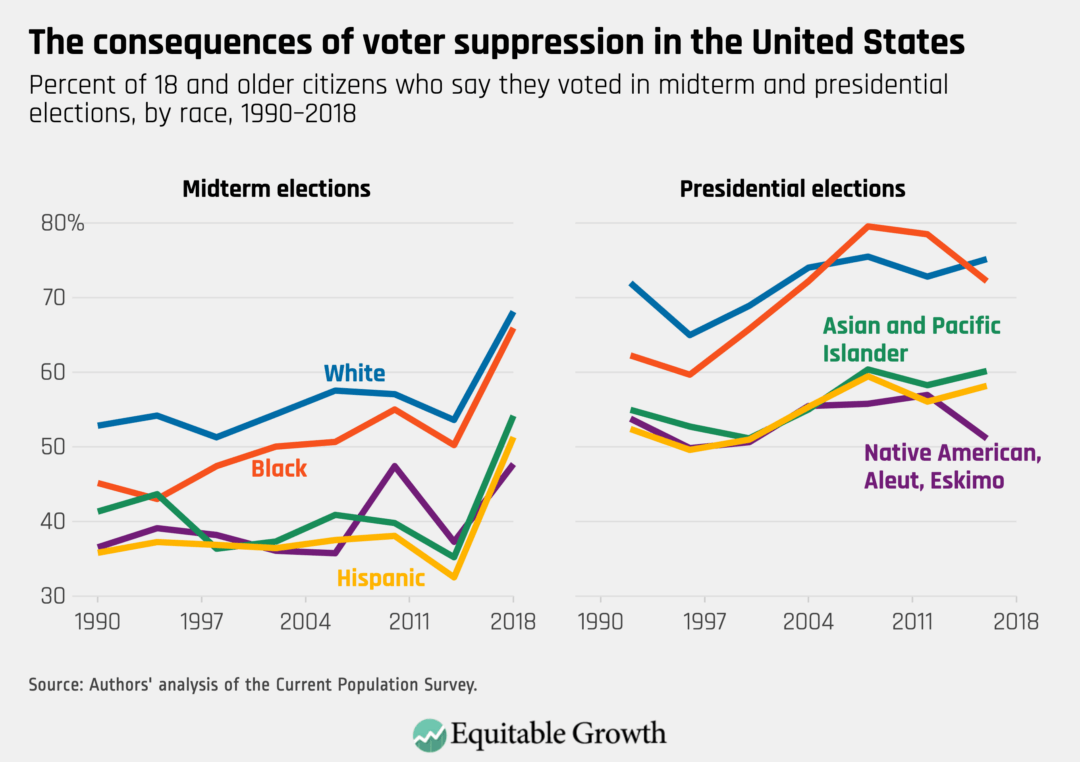

Economic power and political power are intertwined in the U.S. system, as those with market power tend to also wield outsized political power. This relationship between the U.S. economy and U.S. democracy creates a feedback loop that perpetuates economic inequality, instability, and stagnating growth, write David Mitchell, Austin Clemens, and Shanteal Lake in a new report for Equitable Growth. The report looks at the consequences of recent electoral trends in the United States—including underinvestment in electoral infrastructure, the unbalanced campaign finance system, and heightened voter suppression tactics—on voter turnout and representation in the federal government. They examine the many ways in which economic and racial inequality affects who votes, who faces challenges when trying to vote, and who doesn’t vote at all, with repercussions on the populations, policies, and issues that elected officials represent and fight for while in office. They then make several recommendations for policymakers to address the cycle of unequal political power and economic and racial inequality, and to ensure broadly shared and sustainable growth. In an accompanying column to the report, the authors summarize their research and explain why fighting voter suppression would bridge the economic divide between Black and White Americans while kickstarting the U.S. economy.

The “skills gap” narrative, which says that wages will increase when workers acquire more skills or credentials, is false and harmful, and may further entrench vast racial income divides across the U.S. workforce. In fact, Kate Bahn and Kathryn Zickuhr write, even as educational attainment increased for all racial and ethnic groups in the United States in recent decades, the wage divide has worsened between Black and White workers, particularly at higher levels of education, while student debt among Black college graduates remains higher than that of White students for years following graduation. Bahn and Zickuhr review a recent working paper that looks into the link between education level and actual required job skills in order to show how credentialism fosters inequality and reduces upward income mobility. While the vast majority of new jobs posted and filled in recent years required a bachelor’s degree, the skills actually needed in many jobs—in software and technology, for instance—are learned by experience and training rather than formal education. Loosening education requirements may aid in job matching, the working paper’s authors argue, and Bahn and Zickuhr recommend raising wages and improving job quality across the board to reduce inequality and drive growth.

Every month, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics releases data on the U.S. labor market, and today, it released data for the month of January, in which prime age employment increased only slightly, reflecting a weak economic recovery. Bahn and Carmen Sanchez Cumming put together five graphs highlighting important trends in the data, including in the continued racial disparities in unemployment rates and recovery, as well as a still-declining leisure and hospitality sector. And accompanying Jobs Day column by Bahn and Carmen delves into some of the details evident in the newly released data.

In late 2020, Equitable Growth hosted a virtual event highlighting policy ideas for strengthening antitrust enforcement that were put forth in a report authored by seven academic antitrust and competition policy experts. Raksha Kopparam summarizes the report’s main ideas and policy proposals, while reporting on the event’s debate and discussion among participants.

The deadline for our 2021 Request for Proposals is this Sunday, February 7. Be sure to read through the four main issue areas in which the RFP is organized (human capital and well-being; the labor market; macroeconomics and inequality; and market structure), details about who is eligible, and instructions on how to apply on our website.

Links from around the web

Canceling all federal student debt can be done via executive action and would not only help all borrowers but would also begin to close the racial wealth divide in the United States. In an op-ed for The New York Times, Naomi Zewde and Darrick Hamilton explain how this policy idea would have a profound impact on the discriminatory burden of student loan debt for Black Americans. Zewde and Hamilton describe the long history of policies that discriminate against borrowers of color, especially Black borrowers, that has fostered the enormous Black-White wealth divide in the United States. Less household wealth, they write, means taking on more debt to pay for college, which gets compounded when Black workers earn less than their White counterparts upon graduating and entering the labor force. President Joe Biden can use executive authority to cancel all federal student loan debt—and in the absence of full cancellation, Zewde and Hamilton contend, the push to cancel $50,000 of debt per borrower would be a step in the right direction.

The benefits of raising the federal minimum wage from its current $7.25 per hour to $15 per hour would outweigh the costs of doing so, writes The Atlantic’s Annie Lowrey. Though the longstanding theory is that doing so would harm small businesses, raise prices on goods and services, and lead to rising unemployment, evidence suggests that these predictions are overblown. Recent research debunks the claim that higher wages lead to lower employment, with studies of U.S. cities and states, as well as other countries, that have raised the minimum wage finding no evidence of major job losses. As for the idea that “mom and pop” shops would go out of business, Lowrey explains that there are many tried-and-tested creative options these companies can use to adapt to a higher minimum wage. And, countering the idea that raising the minimum wage would cause inflation, Lowrey shows that the price increases from higher labor costs tend to be marginal. Rather than raising overblown and disproven potential costs of raising the minimum wage, she concludes, we should focus on the myriad proven benefits that would be seen and shared across the U.S. economy.

The coronavirus recession is disproportionately affecting working women. U.S. women have lost more than 30 years of gains in the labor market in the months since the virus began closing schools and child care facilities and causing overall employment to drop. And, while solutions to this crisis are complicated, write Fortune’s Maria Aspan and Emma Hinchliffe, the private sector and policymakers alike must act quickly and broadly to address and reverse the scarring that women workers face. Aspan and Hinchliffe run through the various proposals that would help working women amid the coronavirus crisis, including ideas in President Biden’s coronavirus relief package, wage hikes for caregivers, and increased funding for nutrition and housing assistance. Enforcement of existing policies, such as antidiscrimination and overtime regulations, would also support working women, especially Black women and Latina workers, as would increasing funding for state and local governments, where women and workers of color are overrepresented. Finally, Aspan and Hinchliffe explain, ramping up vaccinations to end the pandemic and jumpstart the recovery is key to solving many of these issues and getting people back to work.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “The consequences of political inequality and voter suppression for U.S. economic inequality and growth” by David Mitchell, Austin Clemens, and Shanteal Lake.