Weekend reading: Black Lives Matter edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Equitable Growth President & CEO Heather Boushey made a statement this week on structural racism and economic inequality in the United States:

At Equitable Growth, we stand with our Black colleagues and Black families across the country who every day shoulder the legacy of White supremacy and systemic violence older than the United States itself. We condemn the recent murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, David McAtee, and Ahmaud Arbery and so many, many more Black men, women, and children who have died from police violence, unchecked White civilian power, and structural racism over more than 400 years. Each and every one of their lives matters, and we bear witness to their senseless loss of life.

The statement also addresses the lack of diversity in the field of economics and reiterates Equitable Growth’s commitment to support more Black scholars and elevate their research and policy ideas to the policymaking community, to fund more research that is based on the lived experience of structural racism, and to ensure that the ideas and voices of Black colleagues and economists are represented across our work. As part of this commitment, Boushey continues, we will work to address the roles that the legacy of slavery, white supremacy, and systemic racism play in U.S. politics and the distribution of wealth and power. In this way, we hope to build a better, more just, and more equitable world, where government and society as a whole recognize that Black Lives Matter.

Despite the drop in overall joblessness in May to a still-high 13.3 percent, part-time workers and workers of color in the United States are facing tough times amid the coronavirus pandemic and recession. Black workers are now experiencing a 16.8 percent unemployment rate, and the Hispanic joblessness rate is 17.6 percent, compared to the 12.4 percent rate of their White peers. In addition, in May, part-time workers accounted for almost one-third of the recent unemployment numbers, despite making up less than one-sixth of the U.S. workforce. Kate Bahn and Carmen Sanchez Cumming analyze today’s release of unemployment data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, highlighting the disproportionate impact on these workers and why the current crisis’ impact differs from that of previous recessions.

New research shows that increasing wages for direct-care staff in eldercare facilities can improve safety and health for both facility workers and residents—without reducing the number of workers or the time staff spends with patients. Krista Ruffini summarizes her new working paper, explaining how even a modest increase in wages for nursing home staff increases their tenure with eldercare companies, and reduces the number of health inspection violations and the prevalence of infections and deaths among residents. Ruffini then shows that a 10 percent hike in wages could have reduced the severity of several coronavirus outbreaks at nursing homes across the country and prevented thousands of deaths caused by COVID-19, the disease spread by the new coronavirus. Several policies on the state and local levels could improve the quality of care in nursing homes, she concludes, including raising the federal minimum wage, structuring Medicare reimbursement rates to incentivize high-quality care, and incorporating staffing costs into Medicaid reimbursement rates.

A year ago, Equitable Growth and the Hamilton Project published a book titled Recession Ready: Fiscal Policies to Stabilize the American Economy describing six evidence-based policy ideas that would shorten and ease the next recession using automatic stabilizers tied to economic indicators, such as the unemployment rate. Now, the United States is in the midst of that next economic downturn, with 1 in 4 Americans having lost their job due to the coronavirus recession. On June 8, Equitable Growth and the Hamilton Project will host a virtual event to discuss the significance of the policies proposed in Recession Ready in the coronavirus era and why aid to state and local governments is especially critical now.

Links from around the web

The economics profession has long been struggling to explain racial discrimination in the economy, Peter Coy writes for Bloomberg Businessweek. Coy takes us through the history of economists’ speculations about racial discrimination—largely by White economists, who, “however smart and well-intentioned, can never know how discrimination is experienced and understood by its victims.” Many ignore the impact and legacy of slavery, for instance. What also gets overlooked, he shows, is how ingrained racism and racial discrimination is in our economy and society, from healthcare to housing, from education to policing—and, Coy states, this is made all the more harmful by “the fact that it doesn’t require deliberate hostility to persist.” The economics profession and business industries must grapple with and change the fact that these lived experiences are not being elevated and researched, which only serves to exacerbate racial discrimination.

The coronavirus crisis is making racial inequality even worse in the United States, writes Greg Rosalsky for NPR’s Planet Money. Not only are Black Americans dying at a higher rate of COVID-19 than their White peers, but they are also losing jobs at a higher rate. Studies show that economic inequality will rise as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, and in the United States, Rosalsky says, that undoubtedly means racial inequality will rise as well. The downturn strikes just as African Americans were finally seeing wage growth, after more than a decade of wage stagnation following the Great Recession of 2007–2009. And many Black families already lack the wealth and financial cushions needed to stay afloat during an economic crisis. The disparity between Black-owned wealth and White-owned wealth is being made ever more obvious during this crisis, and will disproportionately put Black workers and their families at a disadvantage coming out of the coronavirus recession.

A recent study by The Brookings Institution’s Makada Henry-Nickie and John Hudak examines how social distancing efforts have been carried out in Black and White communities to see whether social distancing disparities contribute to racial disparities in health outcomes during the coronavirus pandemic. Using mobile tracking device data from Detroit, Henry-Nickie and Hudak show that Black Detroiters were less able to stay home and socially distance than their White peers—not because of personal choices but due to structural differences in the economy and the higher proportion of Black workers in so-called essential jobs. Black and poor communities have not had the option to stay home, telecommute, or remain physically distant, while their White and well-off neighbors have, and the study clearly shows that this has had a large impact on their infection and death rates from COVID-19.

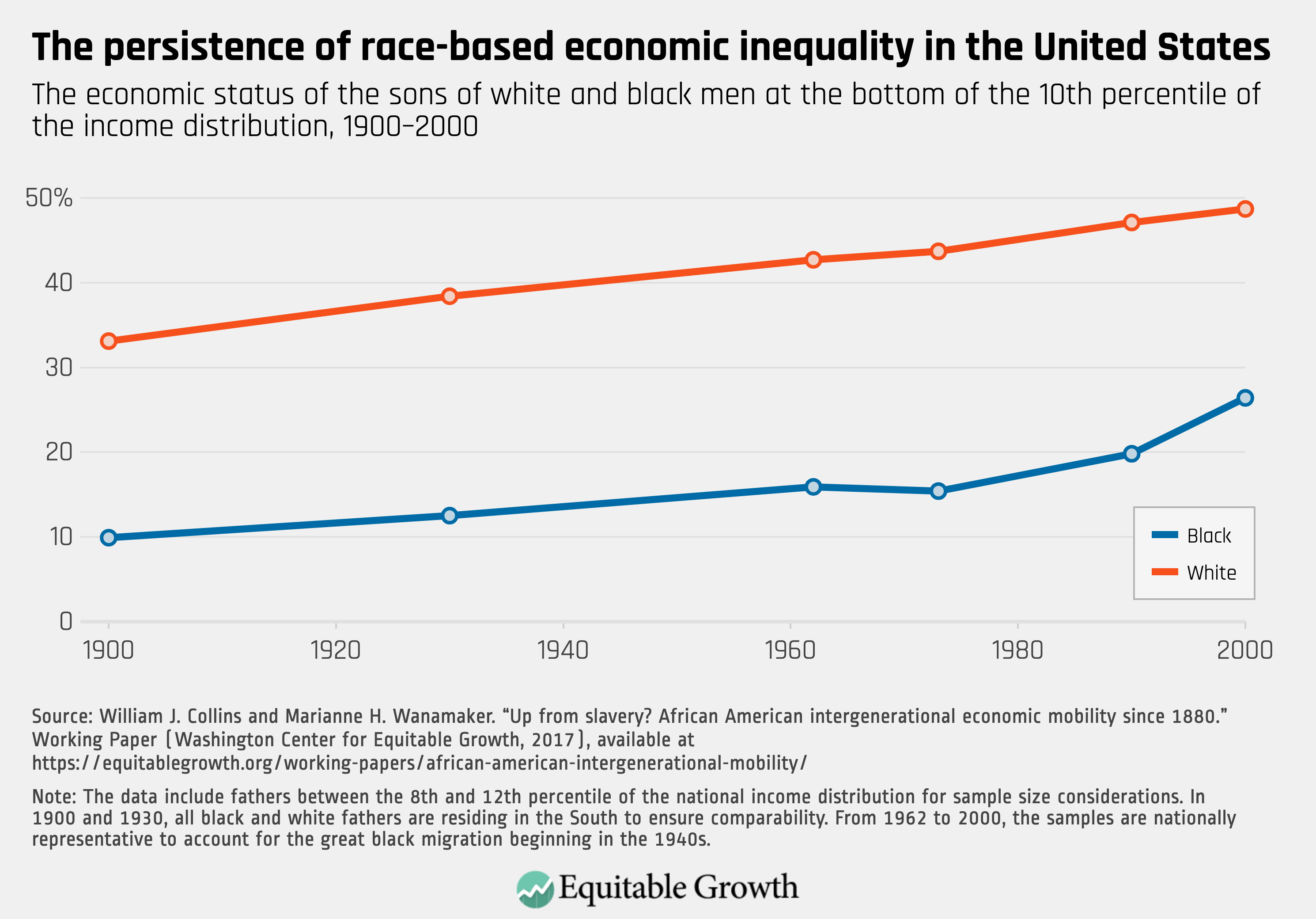

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s 2019 article, “For Juneteenth: A look at economic racial inequality between white and black Americans” by Liz Hipple and Maria Monroe.