Weekend reading: How to return to work safely edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

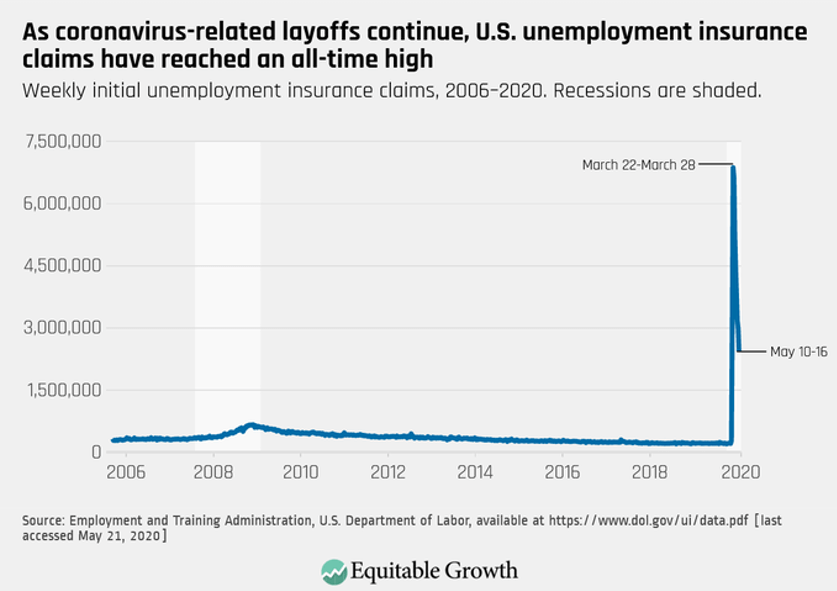

It’s more important than ever to make sure those who do get back to work are protected against the backdrop of weekly Unemployment Insurance claims data showing that 1 in 4 American workers filed for UI benefits since the coronavirus pandemic began in mid-March. The most effective way to do so will be to contain the coronavirus through vigorous testing and contact tracing, Heather Boushey writes, noting that failing to do so will risk another spike in cases of and deaths from COVID-19, the disease spread by the new coronavirus, as well as prolong an already painful recession. Protecting those on the front lines of the battle against coronavirus will protect the rest of us—not offering these workers the safety they deserve risks our health and our economy. Boushey provides proposals to make sure workers feel safe returning to their jobs, including mandated paid sick days and personal protective equipment to essential workers, among others.

One group of essential workers that is gaining prominence in the discussions around protecting front-line workers is warehouse workers, who often are forced to accept unfair scheduling practices and are being exposed to COVID-19 at high rates due, in part, to unsafe work conditions and a lack of employer-provided protections. Back in February, Equitable Growth hosted a convening on scheduling practices in the U.S. warehouse sector, bringing together advocates, researchers, and warehouse workers to find solutions to job-quality issues facing the industry. Sam Abbott and Alix Gould-Werth explain how scheduling practices and poor work conditions affect job quality in the warehouse sector and discuss how researchers interested in studying this sector can engage in these areas of study.

Income inequality is higher and rising faster than policymakers probably realize, write John Sabelhaus and Somin Park. Using data from the Survey of Consumer Finances and comparing them to the widely used Congressional Budget Office measures of household income, Sabelhaus and Park show that CBO estimates don’t consider two main drivers of income inequality: uncaptured noncorporate business income and the gap between realized and unrealized capital gains income. Incorporating the Survey of Consumer Finances addresses these shortcomings, the co-authors explain, highlighting how these two areas can shed light on income inequality’s growth over the past few decades and the dynamics of inequality in the United States.

Equitable Growth has launched a new lecture series, which will be virtual for the time being, discussing evidence-based research on policy ideas to ensure sustainable and broad-based economic growth. The first lecture in the series featured a conversation between Boushey and Claudia Sahm, director of macroeconomic policy, on specific ways to deal with the health and economic crises caused by the coronavirus outbreak. Sahm urged bold actions by policymakers to prevent economic freefall and save lives. She also discussed the role of the Federal Reserve, automatic stabilizers for the economy, and targeting relief to the most vulnerable households and communities.

Equitable Growth announced its two new Dissertation Scholars this week. This program provides financial and professional support to doctoral candidates as they write their dissertations, bringing the scholars to Washington to gain familiarity with the policy process and current policy discussions. Congratulations to Angela Lee of Harvard University and Matthew Staiger of the University of Maryland, College Park, who will be joining Equitable Growth for the 2020–21 academic year!

Links from around the web

Essential workers are putting their lives and the lives of their loved ones at risk to keep the rest of us safe, healthy, and fed. They deserve more than basic protections and the minimum wage, argues Suresh Naidu in The Washington Post. But many are not being provided with adequate pay or what they need to feel safe at work—and have almost no leverage to get it. With unemployment at its highest rate since the Great Depression, these workers can’t quit or move to other jobs. Even with expanded Unemployment Insurance from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, those who leave their jobs voluntarily are not eligible to receive benefits. Employers currently wield a lot of power in the labor market, writes Naidu, and they have been using it to keep hazard pay low and worker safety protections minimal at best. We owe it to these front-line fighters to push for better working conditions and higher pay, and Naidu offers several ideas of how to do so.

The latest stimulus bill proposed by House Democrats offers much-needed relief to struggling Americans in many ways. But, writes Ezra Klein on Vox, it’s missing an important policy proposal that would be the most effective, surefire way to ensure continued support during the coronavirus recession and recovery: automatic stabilizers. The main idea behind automatic stabilizers is to provide support to those who need it based on the economic conditions of the day, not political whims or arbitrary expiration dates, explains Klein. The policy is popular with people across the political spectrum, and has broad support from researchers and economists (including Equitable Growth, whose book, Recession Ready, published last year with The Hamilton Project, focuses on various automatic stabilizer proposals). Klein investigates the reason automatic stabilizers were removed from the stimulus package and why they’re actually cheaper than the alternative.

All the recent concern about high inflation after the coronavirus recession is probably misplaced, says Neil Irwin in The New York Times’ The Upshot blog, and may actually risk us ignoring or not adequately addressing the crisis at hand. Though he says it’s worth looking into the concerns about inflation, especially considering how widespread these concerns are, he adds that it’s also difficult to predict what will happen with inflation rates—and it shouldn’t be the worst-case scenario for policymakers. “In many ways,” continues Irwin, “an inflation surge in the early 2020s would be a signal that all the efforts being taken now (to flood the financial system with cash, to prop up smaller businesses and aid unemployed people) had worked—preventing a deflationary spiral akin to what happened in the Great Depression.”

We’ve said it before, and we’ll probably say it again: Millennials are economically the unluckiest generation in U.S. history. They entered the workforce during and after the Great Recession of 2007–2009, never really had a chance to recover from that downturn, and are now being hit by a recession again, right when they should be entering the peak years of their careers, earnings-wise. Andrew Van Dam put together several charts for The Washington Post highlighting how the average millennial’s economic and labor force experience will have lasting negative effects on their earnings, wealth, and other economic milestones such as homeownership.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s Twitter feed after this week’s release of Unemployment Insurance claims data.