Weekend reading: The new coronavirus edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

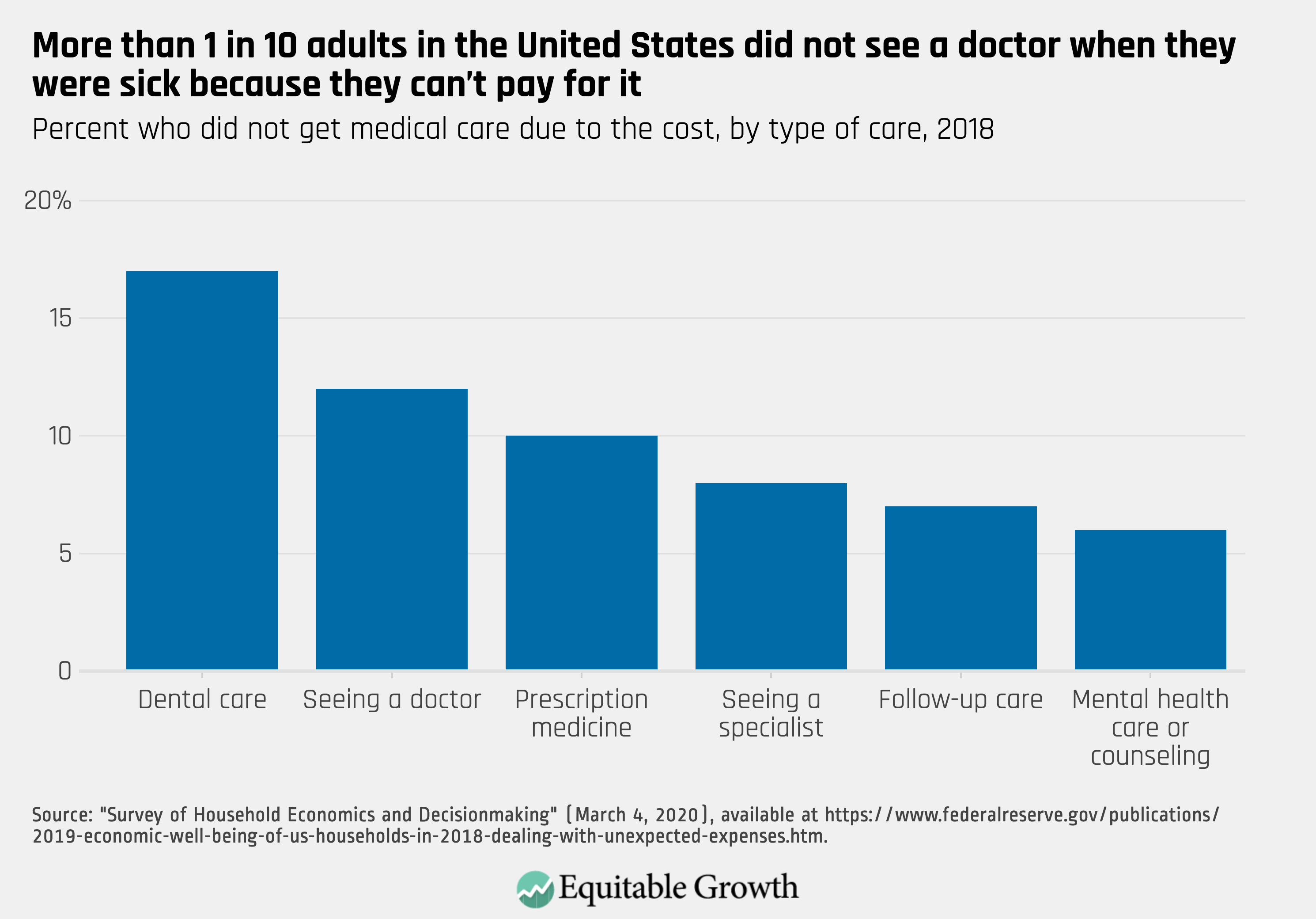

While the new coronavirus is first and foremost a public health crisis, it is also a threat to our economy, writes Claudia Sahm. The Federal Reserve lowered interest rates by 0.5 percentage points this week in efforts to calm the zig-zagging financial markets and otherwise stabilize the economy. And while the Fed does not control market activity, it does play an important supporting role. Its actions this week were clearly designed to help ease fears and uncertainty in the financial market, as well as help out businesses and individual borrowers taking on debt. But monetary policy cannot act alone here—fiscal policy responses are needed as well. Sahm recommends that Congress and the Trump administration act quickly to tamp the spread of the virus and any economic distress it may cause, and implement automatic economic stabilizers in case of a recession. And, considering that 4 in 10 Americans cannot readily afford a $400 medical expense, it is likewise essential for the federal government to provide people with the financial support they need to get healthy, stay healthy, and keep their loved ones healthy.

A working paper released this week shows how Gross Domestic Product data determine how reporters and journalists present the economic debate to the public—despite the disconnect between the numbers presented each quarter and the lived experience of most Americans. Austin Clemens describes the research, which looked at economic articles from more than 30 newspapers across the United States since 1980 and finds that the tone of the articles closely correlates with the fortunes of the top 1 percent of income earners—while being uncorrelated with income growth for the bottom four quintiles of income earners. This bias is not due to the ideological leanings of reporters but rather to their reliance on numbers such as GDP to track the state of the U.S. economy. Clemens explains how this groundbreaking study shows we desperately need a new measurement of economic growth that doesn’t just reflect increasing incomes among the rich. Luckily, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis recently released a prototype of the first-ever statistics measuring how U.S. personal income is distributed across the income ladder. Read our press release on the new tool.

Another new working paper looks at the relationship between an individual’s FICO credit score, wealth accumulation, race, and incarceration history. The authors, William Darity, Jr., Sarah Elizabeth Gaither, and Monica Garcia-Perez, looked at a sample from Baltimore of white and black individuals with and without a history of incarceration, as well as their credit score information. They found that having a personal history of incarceration is not only associated with lower credit scores but also with lower wealth accumulation—which affects more black Americans than white Americans, given that blacks are overrepresented in the U.S. prison population. But even outside of incarceration, black Americans are still at a disadvantage: The authors, who also penned a blog post about the research, find that blacks who have never been incarcerated, “despite having more assets and less debt, have average FICO credit scores that are similar to white who have ever been incarcerated.”

March is Women’s History Month, and it started with some good news for women in the workforce: The U.S. unemployment rate shows an exceptionally good environment for workers in general, and female workers in particular, writes Carmen Sanchez Cumming. Only 3.5 percent of women are actively looking for a job and can’t find one, a 65-year low, and the gender gap in unemployment is narrow, with unemployment for men at 3.6 percent. But how has this trend actually affected women in the economy? Though the media often reports on jobs lost in production and manufacturing—two areas dominated by male workers—Sanchez Cumming explains that typically female-dominated jobs in office and administrative support have likewise been lost in high numbers, and the female-dominated fields with increasing openings, such as hospitality and healthcare, do not provide jobs with high security or strong benefits.

Age discrimination is rampant in the U.S. economy, particularly with regard to hiring and firing, writes David Mitchell. Although it is technically illegal, age discrimination persists due, in part, to several decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court that have undermined laws to prevent it and to a lack of enforcement resources. As our population ages and workers remain in the labor force longer, this issue is of growing importance and requires our attention, says Mitchell. He reviews recent studies proving that age discrimination is widespread in hiring, firing, and on the job, and argues that Congress must pass a law to protect older workers that actually stands a chance of being followed by employers and enforced by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Links from around the web

The new coronavirus is very likely to do meaningful damage to the U.S. economy, writes Neil Irwin for The New York Times’ The Upshot. It may even send us into a recession the likes of which we are unprepared to reverse because “this particular crisis is ill suited to the usual tools the government has to stabilize the economy.” Lowering interest rates can help lower borrowing costs and tax rebates can put money into consumer’s pockets, Irwin continues, but neither option can restock empty store shelves or produce goods made in temporarily shut-down factories. This recession would be caused by a so-called supply shock, or the reduction in our economy’s ability to make things—particularly pharmaceuticals and electronics, two industries with complex global supply chains—which could lead to a demand shock. And while economic policy can’t do much about a supply shock, it can help prevent a resulting demand shock.

The lack of paid sick leave in the United States will only make the new coronavirus outbreak worse, “leaving many with little choice but to go to work while ill, transmitting infections to co-workers, customers and anyone they might meet on the street or in a crowded subway car,” writes Christopher Ingraham for The Washington Post. Looking at a study of cities with paid sick leave and rates of influenza, Ingraham shows how the implementation of a paid leave program reduces infection rates by as much as 40 percent, relative to those cities without paid sick leave programs. This issue is most prevalent in some services industries, where workers such as those who prepare our food and care for our children and the elderly intermingle with two populations at high risk of developing serious and potentially life-threatening illnesses as a result of viral infections. As the new coronavirus continues to spread throughout the United States, Ingraham argues that the issue of paid leave is more important than ever for policymakers to consider.

If women in the United States earned the minimum wage for all the unpaid labor they do around the house and in caregiving, they would have earned $1.5 trillion in 2019. Globally, women’s unpaid labor is worth almost $11 trillion—or more than the combined revenue of the 50 largest companies on the Fortune Global 500 list. These staggering statistics come from Gus Wezerek and Kristen R. Ghodsee in The New York Times. This unpaid labor is neither included in GDP calculations nor factored into other measures of economic growth, Wezerek and Ghodsee write, probably because it is widely assumed this work should be done within the family and for free. Though in the United States, the gender gap in who performs this unpaid labor has narrowed, women still perform a disproportionate amount of it, on top of their full-time jobs.

In 2019, Target Corporation raised the minimum wage it pays its employees to $13 per hour, and it plans to raise wages again this year, to $15 per hour. But as Michael Sainato reports for The Guardian, the wage increases have led to hours being cut (and benefits being lost as a result) and workloads being doubled. Target rolled out its so-called modernization plan last year to increase efficiency, but workers argue that the plan is largely a response to Amazon.com Inc.’s market domination, saying Target now expects them to be both warehouse workers and customer-service workers—in fewer hours per week. Sainato speaks to several Target employees from across the United States about their experience after the wage hike last year, most of whom said their incomes have gone down due to the reduction in hours and many of whom no longer qualify for employer-provided insurance as a result.

Friday Figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “U.S. economic policymakers need to fight the coronavirus now” by Claudia Sahm.