Brad DeLong: Worthy reads on equitable growth, March 22–28, 2019

Worthy reads from Equitable Growth:

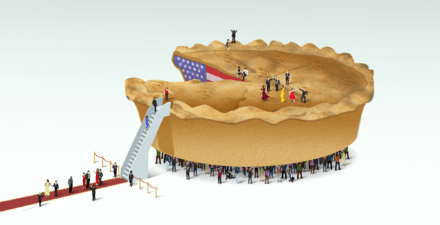

- This week’s absolute must-read, from Greg Leiserson, Will McGrew, and Raksha Kopparam. It is excellent. I would note that it does not get much into the political economy of wealth taxes—that one goal of them is to persuade the wealthy to distribute their wealth and thus reduce the amount of control over society that they exercise. Read their “Net Worth Taxes: What They Are and How They Work,” in which they write: “Notably, a business does not pay tax on its assets. Instead, shareholders pay tax on the value of the business … The revenue potential of a net worth tax in the United States is large, even if applied only to the very wealthiest families. The wealthiest 1 percent of families holds $33 trillion in wealth, and the wealthiest 5 percent holds $57 trillion. The burden of a net worth tax would be highly progressive. The wealthiest 1 percent of families holds about 40 percent of all wealth … Taxes on wealth—including property taxes, net worth taxes, estate taxes, and capital gains taxes, among others—are ubiquitous in the developed countries that make up the … OECD … Assets have value because of the income (implicit or explicit) they are expected to generate. As such, taxing wealth through a net worth tax and taxing income from wealth through a tax on investment income can achieve similar ends.”

- Note this and note this well: The principal reason U.S. relative female labor-force participation is lagging behind OECD peer economies is that our society is markedly less friendly to women working outside the home than our peer societies are. Read Elisabeth Jacobs and Kate Bahn, “Women’s History Month: U.S. Women’s Labor Force Participation,” in which they write: “A change in direction for U.S. policies related to childcare and early education, along with a strong national paid leave policy for family leave could help to reverse the downward trend of U.S. women’s labor force participation and put it back on the same path that most other developed countries are on.”

- From 2016, this paper did not get the attention I believe it deserved: How higher labor standards affect how firms behave on the ground. This type of work is extremely valuable—indeed, essential to place statistical patterns in proper context—is difficult to do, and so needs to be highlighted more. Read T. William Lester, “Inside Monopsony: Employer Responses to Higher Labor Standards in the Full-Service Restaurant Industry,” in which he writes: “Employer responses to higher labor standards through a qualitative case comparison of the full service restaurant industry … San Francisco—where employers face the nation’s highest minimum wage, no tip credits, a pay-or-play health care mandate, and paid sick leave requirements—and … North Carolina’s Research Triangle region—where there are no locally-enacted labor standards … higher labor standards led to wage compression in San Francisco even while some employers continued to offer greater benefits to reduce turnover. Employers in San Francisco exhibit greater investment in finding better matches and tend to seek higher-skilled, more professional workers, rather than invest in formal in-house training. Finally, higher wage mandates in San Francisco have exacerbated the wage gap between front-of-house and back-of-house occupations—which correlate strongly with existing racial and ethnic divisions. Initial evidence shows that some employers have responded by radically restructuring industry compensation practices by adding service charges and in some cases eliminating tipping.”

- Somehow, I have not yet noted here the existence of Rodney Andrews, who is now—with Logan Hardy and Marcus Casey—merging the Raj Chetty and others’ Equality of Opportunity dataset with other information sources in what looks, to me, like a very promising line of research. Read Bradley Hardy, Rodney Andrews, Marcus Casey, and Trevon Logan, “The Historical Shadow of Segregation On Human Capital And Upward Mobility,” in which they write: “Regional differences in opportunity might be explained not only by contemporary characteristics but also by historical disparities. The researchers will merge the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) with Raj Chetty and others’ Equality of Opportunity dataset, and the Logan-Parman index of inequality.”

Worthy reads not from Equitable Growth:

- The old “secular stagnation” of the 1930s and 1940s was a fear that the world was approaching satiation with respect to things that it would be profitable to build. The new secular stagnation is much more a fear of growing monopoly power and a growing desire for safety. It is thus a very different thing—or, rather, two different things happening alongside each other. Read Emmanuel Farhi and Francois Gourio, “Accounting for Macro-Finance Trends,” in which they write: “Developed economies have experienced large declines in risk-free interest rates and lacklustre investment over the past 30 years, while the profitability of private capital has increased slightly. Using an extension of the neoclassical growth model, this column identifies what accounts for these developments. It finds that rising market power, rising unmeasured intangibles, and rising risk premia play a crucial role, over and above the traditional culprits of increasing savings supply and technological growth slowdown.”

- A clever take from The Economist, using the largest building in the world in Sichuan as a microcosm of the Chinese economy. Read “The Story of China’s Economy as Told Through the World’s Biggest Building: The Global Centre,” in which the magazine writes: “The world’s biggest building got off to a bad start. On the eve of its opening, Deng Hong, the man who built the mall-and-office complex, disappeared … swept up in a corruption investigation just before the building’s doors opened in 2013. The media focus shifted to his hubris and his wasteful, pharaonic venture. Inside, it had a massive waterpark with an artificial beach, an ice rink, a 15-screen cinema, a 1,000-room hotel, offices galore, two supersized malls, and its own fire brigade, but just a smattering of businesses and shoppers. It became a parable for the economy’s excesses and over-reliance on debt. Today, more than 5 years on, the story has taken a series of surprising turns. For one, the building is not a disaster. During the summer, the waterpark is crowded. The mall has come to life, a testament to the rise of the middle class. The offices are a cauldron of activity: 30,000 people work there in every industry imaginable, from app design to veterinary care. Mr. Deng has been released and is back in business, declaring last summer that he had a clean slate.”

- It is pretty clear that the post-2008 U.S. labor market is such that it totally deranged the unemployment rate as a meaningful measure of labor market slack. Read Josh Bivens, “Predicting Wage Growth with Measures of Labor Market Slack: It’s Complicated!,” in which he writes: “Why have wages grown so slowly in recent years despite relatively low unemployment rates? This puzzle has dominated economic commentary … Since 2008, the share of adults between the ages of 25 and 54 who are employed (or the ‘prime-age EPOP’) has predicted wage growth better than the unemployment rate. But even the prime-age EPOP has done a poor job at predicting wage growth since 2008, compared with both its own predictive power pre-2008 and the predictive power of the unemployment rate in earlier periods.”

- Marty Feldstein gained a nearly infinite bank of credit for being brave, honorable, and honest with respect to our fiscal policy choices in the early 1980s. But he is running his balance down rapidly. Over the past 2 years, Feldstein has argued sequentially that (a) there is no need to worry about Republicans’ enacting law to increase the debt because they won’t, (b) Republicans’ enacting law to increase the debt won’t matter because debt service will still fall as a share of Gross Domestic Product as the result of their policies, (c) debt service is about to rise rapidly because interest rates are going to go way up, and now (d) we must cut entitlements a lot in order to “avoid economic distress.” The best that can be said is that this shows extreme naivety about what Republican politicians do and gross inconsistency with respect to his vision of how the economy works. August 29, 2017: “The new legislation would … boost domestic corporate investment … Although the net tax changes may widen the budget deficit in the short term, the incentive effects of lower tax rates and the increased accumulation of capital will mean faster economic growth and higher real incomes, both of which will cause rising taxable incomes and lower long-term deficits … I am optimistic that a tax reform serving to increase capital formation and growth will be enacted, and that any resulting increase in the budget deficit will be only temporary.” November 27, 2017: “The economic benefits resulting from the corporate tax changes will outweigh the adverse effects of the increased debt.” February 27, 2018: “Long-term interest rates in the United States are rising, and are likely to continue heading up.” Now, read Martin Feldstein, “The Debt Crisis Is Coming Soon,” in which he writes: “The most dangerous domestic problem facing America’s federal government is the rapid growth of its budget deficit and national debt … Federal debt will probably surpass 100 percent much sooner than 2028. If discretionary spending increases, debt growth will jump to 100 percent even quicker. When America’s creditors at home and abroad realize this, they will push up the interest rate the U.S. government pays on its debt. That will mean still more growth in debt. … To avoid economic distress, the government either has to impose higher taxes or reduce future spending. Since raising taxes weakens incentives and further slows economic growth—worsening the debt-to-GDP ratio—the better approach is to slow government spending growth … Thus the only option is to throw the brakes on entitlements.”