Weekend reading: Worker scheduling practices edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

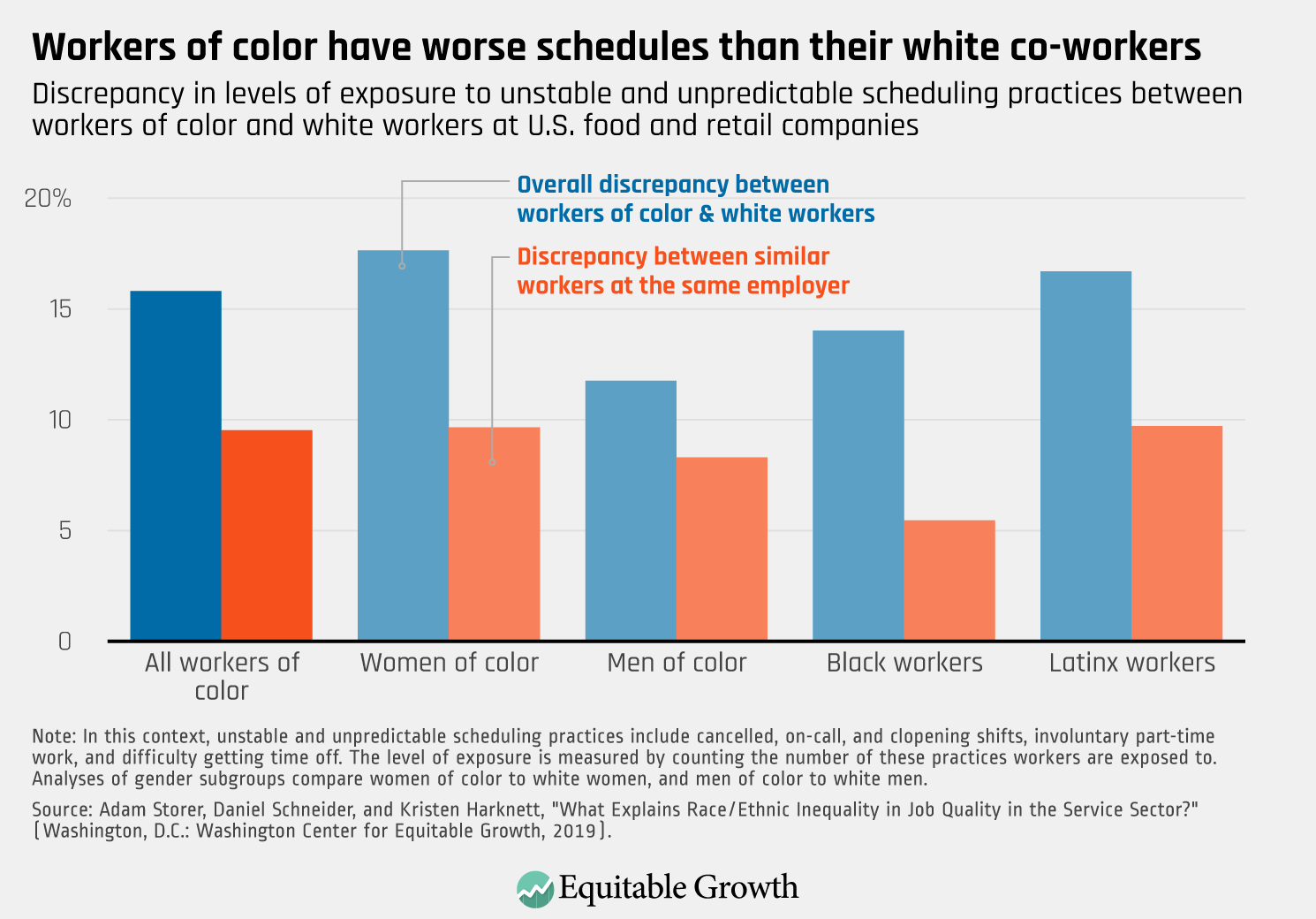

How do scheduling practices affect working families, particularly families of color, in the United States? A series of working papers released this week shows that not only are low-quality and unpredictable schedules pervasive among low-wage workers, but also that these schedules perpetuate racial and ethnic inequality across the country. The researchers surveyed 30,000 workers at 120 of the largest retail and food-service companies in the United States to find out who suffers the most from these schedules, and discovered that black and Hispanic women tend to have the worst schedules, while white men have the best ones. They also discovered that the children of those with the worst schedules behave worse and have less consistent childcare than those with parents who have better schedules. Cesar Perez and Alix Gould-Werth put together 10 charts highlighting the main findings of the research, which was also covered in The New York Times The Upshot blog.

Despite the evidence that desegregation boosts outcomes for low-income and minority students without negatively affecting their better-off and white peers’ outcomes, school segregation remains a problem across the nation. In fact, though the United States saw a large decline in black-white school segregation from the 1960s through the 1980s, in the years since then, desegregation has stalled and resegregation has actually increased, according to a report by former Research Assistant Will McGrew. In a blog post covering the report, Liz Hipple describes how McGrew makes it clear that school segregation is not an inevitable outcome of individual choices or preferences for “good” school districts, but rather that policy and legal decisions shape these preferences by continuing to tie school funding to local property taxes. Not only does this limit opportunities for individual students to achieve their own full potential, it also obstructs future dynamism and growth in the U.S. economy. McGrew recommends various policy options to reverse the trend of resegregation and put us back on the path to progress.

Equitable Growth President and CEO Heather Boushey testified before the Joint Economic Committee this week in a hearing on “Measuring Economic Inequality in the United States.” In her testimony, Boushey argued that one of the most important ways to fight inequality in the United States today is to properly track and measure it—namely, by adding measures of growth within income quantiles to the Bureau of Economy Analysis’ National Income and Product Accounts to better reflect the realities of the modern economy.

Equitable Growth Steering Committee member Jason Furman testified today before the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law. He discussed concentration in digital platforms, and how competition would benefit consumers, touching on ways to protect this competition such as more robust merger enforcement and regulations.

Be sure to head over to Brad DeLong’s latest worthy reads for his takes on must-see content from Equitable Growth and around the web.

Links from around the web

More than 9 million people work in food service, and 16 million more work in the retail sector, and according to estimates one-third of these workers receive less than one week’s notice for their schedules. As a result, these workers tend to have higher stress levels, more volatile income, less stable childcare options, and often have to get second jobs in order to make ends meet. Stephanie Wykstra explains on Vox the fight for fair workweek policies, who would be most affected, how these policies would help workers, and the challenges facing supporters in getting companies to comply.

The United States has never been richer, writes Eric Levitz in New York Magazine’s The Intelligencer. In fact, if wealth were evenly distributed across the United States today, each individual would have close to $300,000 and every family of four would be millionaires. So, why is it that middle- and working-class households are working way more and earning way less than they were a few decades ago? Levitz argues that three policy failures that have led us here: the dramatic decline in wages and worker bargaining power; the ever-increasing and unaffordable costs of housing, healthcare, and education; and the failure to modernize the social safety net.

At least half of the Democratic candidates for president in the 2020 race have put forward robust labor platforms touching on ideas from broadening union membership to banning noncompete agreements to treating independent contractors as employees, reports Noam Scheiber for The New York Times. One of the more striking of these proposals is the idea known as sectoral bargaining, which would allow workers to bargain with employers on an industrywise basis rather than with individual employers, potentially increasing wages for millions of workers at a time—even those who aren’t unionized. Scheiber hypothesizes that the large number of candidates supporting sectoral bargaining and other labor platforms likely reflects stagnant wage growth, increasing economic insecurity, and deepening inequality in the United States.

Rather than hitting the glass ceiling at the very top of the management ladder, new research suggests that women may face obstacles to advancing higher up much earlier in their careers—namely, at the very first rung of the management ladder. In fact, writes Vanessa Fuhrmans for The Wall Street Journal, “men outnumber women nearly 2 to 1 when they reach that first step up—the manager jobs that are the bridge to more senior leadership roles.” And, according to the study, it’s not because women are pausing there to raise children or that they have less ambition than men.

Friday Figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “How U.S. workers’ just-in-time schedules perpetuate racial and ethnic inequality,” by Cesar Perez and Alix Gould-Werth.