Weekend reading: Unemployment, low-wage workers, and the new coronavirus edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

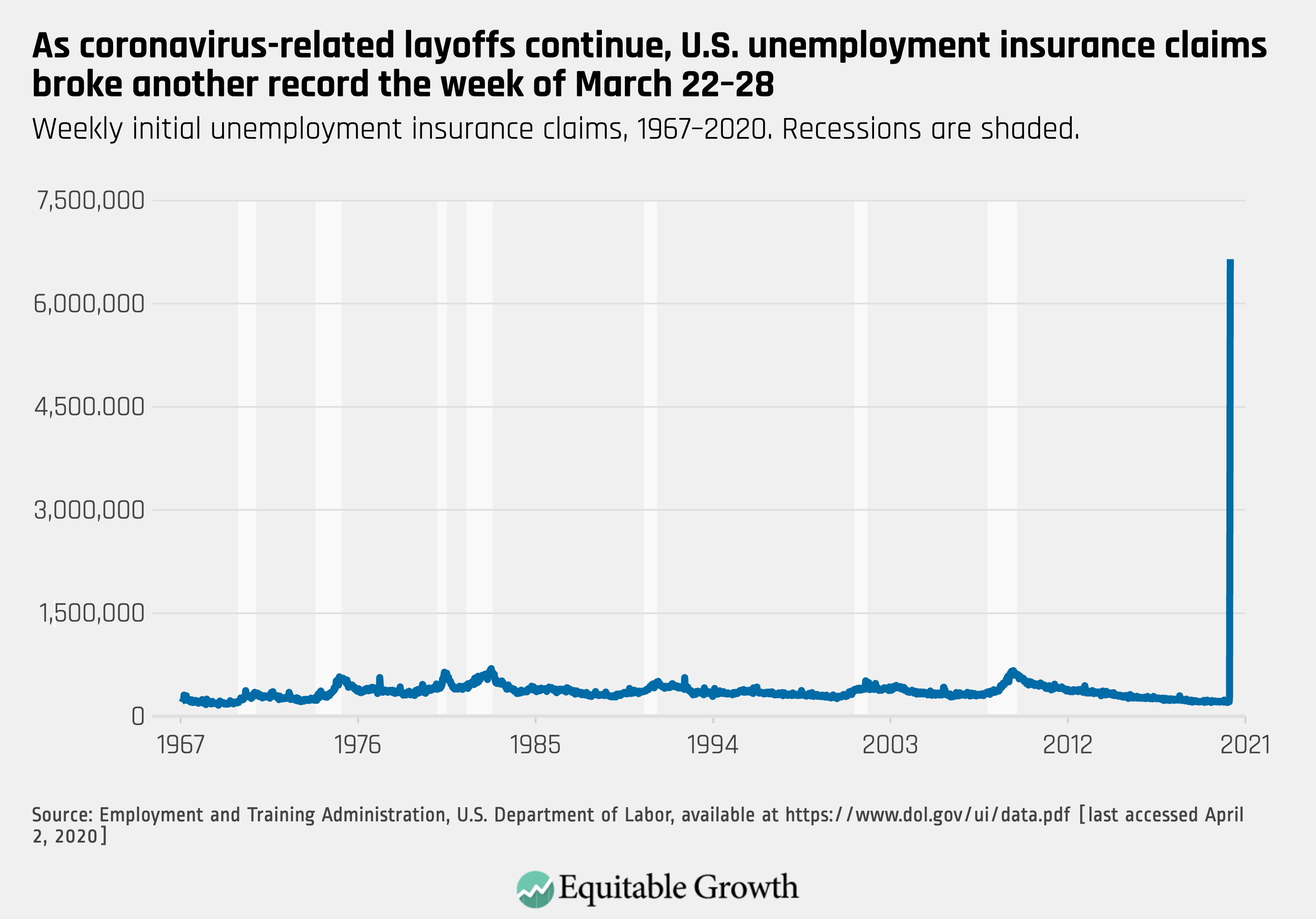

Today’s Jobs Day report, along with yesterday’s record-breaking Unemployment Insurance claims report, show the U.S. economy in crisis, write Kate Bahn and Carmen Sanchez Cumming. The jobs report includes data through March 14—which was before any city or state ordered the official closure of nonessential businesses, but after many had seen drops in demand or voluntarily shut down—and shows that retail and hospitality workers faced big declines in hours worked. The workers in these industries also tend to be paid the least, have the most insecurity, and lack access to benefits such as paid sick days, meaning a severe hit to these sectors will hurt the most vulnerable workers in our economy. These reports offer just a preliminary look at how workers will be affected by the coronavirus recession, and almost certainly mark the end of the longest economic expansion in U.S. history.

Low-wage workers are particularly at risk of being laid off during this coronavirus recession because they are concentrated in the service, hospitality, and food sectors, some of the hardest-hit areas of the U.S. economy. As a result of their higher economic risk, they also face more severe psychological effects. Alix Gould-Werth and Raksha Kopparam put together a series of 10 charts highlighting data from surveys done in March 2020 of workers in these industries in a typical U.S. large city on how their lives have been affected by the new coronavirus. While the surveys were done prior to the enactment of the $2.2 trillion stimulus package last week—which expanded Unemployment Insurance, among other things—the data reveal that policymakers must act quickly to facilitate access to these new and expanded supports for low-wage workers. Even so, many of those most in need may not receive the help they need to soften the economic and psychological blows of the economic downturn.

One of the most vital pieces of the stimulus package enacted last week is the direct cash benefits for tax-paying U.S. citizens, especially considering the record-breaking numbers of Unemployment Insurance claims that have been filed over the past two weeks. Michigan State University economist and Equitable Growth Research Advisory Board member Lisa Cook recommends the government prioritize at-risk low-wage workers—44 percent of all U.S. workers—when distributing the $1,200 checks because they are typically their families’ primary wage earners and often live paycheck to paycheck. Without an income, and without the cash benefits, many will not be able to pay their bills or patronize local businesses, which will only worsen the effects of the coronavirus recession barreling forward. Cook suggests mobile payments as an option for the government to allocate the cash benefits quickly and efficiently, considering how high smartphone penetration is among the U.S. population: 81 percent of U.S. adults have a cell phone capable of receiving and making mobile payments.

As U.S. policymakers and workers alike saw in data released this week and last week, the Unemployment Insurance system in the United States is being overloaded with claims by workers who have lost their jobs as a result of the new coronavirus recession. But research suggests that only 25 percent of those who lose their jobs or have their hours cut actually gain access to unemployment benefits, due to weaknesses in federal law and restrictions at the state level. Arindrajit Dube explains why Unemployment Insurance is a vital and effective mechanism to provide social insurance in times of economic distress, and why the government needs to expand access for all workers who lose their jobs or whose hours are cut now. He proposes five ideas—some of which were incorporated in last week’s $2.2 trillion stimulus package and some of which were not, but all of which would help workers in need.

There is little doubt the U.S. economy is facing a recession due to the onset of the coronavirus pandemic. Acknowledging this, it is important to keep in mind research that shows how recessions have long-lasting negative impacts on employment and earnings for those workers who happen to be entering the workforce during economic downturns. These effects, writes Liz Hipple, are proven to last longer than the recession period itself, lingering for years and even decades afterwards. In looking at the Great Recession of 2007–2009, research shows that not only did employment rates drop for workers entering the labor force (relative to older workers), but also that these younger workers also earn less in the early years of their careers and have lower rates of employment throughout the course of their careers.

A quick reminder: This past Wednesday was Census Day in the United States. (Don’t forget to complete your census forms as soon as possible!) Raksha Kopparam explains the history of the census, and reviews the challenges to collecting census data during the coronavirus pandemic and recession.

Links from around the web

France is using a different approach to try to stave off the worst of the economic effects of coronavirus and ensure a speedy economic recovery: preventing companies from going under in the first place and keeping workers from losing their jobs. Liz Alderman reports for The New York Times that the French government is spending around $50 billion to pay businesses not to lay off workers, delaying payments on taxes and loans, and offering hundreds of billions of euros in state-guaranteed loans to struggling businesses. The goal is to avoid a repeat of the 2008 financial crisis so that the end result is hopefully less severe and devastating.

The coronavirus recession is making clear the U.S. economy was not as strong as it seemed, despite years of reports of Gross Domestic Product growth and low unemployment rates, writes David J. Lynch for The Washington Post. A record-long expansion and years of low interest rates could make it harder for the economy to recover from a recession. Excessive corporate debt has left a huge part of the economy vulnerable, and many companies will require additional funding in order to prevent closures within three to six months—and even then, it might not be enough for many to stay afloat. These financial weaknesses will determine how the U.S. economy fares during and after this downturn, and which companies—large or small—will survive.

As stay-at-home orders become prevalent and white-collar employees begin working from home, many workers in grocery stores, warehouses, and pharmacies still have to show up at their workplaces and risk catching COVID-19, the name of the disease caused by the new coronavirus. So, is your grocery delivery worth a worker’s life? Steven Greenhouse poses this important question in The New York Times this week, after workers across the nation and across industries threatened to or actually went on strike to protest a lack of employer protections and care against the coronavirus outbreak. “These workers are demanding what everyone else wants during the worst epidemic in a century—safety,” writes Greenhouse. “They feel their companies are taking them and their safety for granted, and they don’t want to risk their lives for a paycheck, often a meager one.” More walkouts are almost certain to happen in the coming weeks, until government and business leaders protect those who are risking so much to keep us fed and healthy.

A New York City study highlights the economic inequalities of the coronavirus pandemic by mapping the outbreak by ZIP code, clearly showing that wealthier parts of the city have the fewest number of coronavirus cases. Julia Marsh covers the study in the New York Post this week, explaining how harder-hit districts tend to house poorer residents, who typically are those front-line workers, such as grocery store clerks and emergency responders, who still have to commute into work during the pandemic. Neighborhoods with fewer than 200 cases have more white-collar workers, who are more likely to be telecommuting.

Friday Figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “First Jobs Day report since the onset of the coronavirus recession exposes a U.S. labor market in crisis” by Kate Bahn and Carmen Sanchez Cumming.