Weekend reading: The economics of equal opportunity for all edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

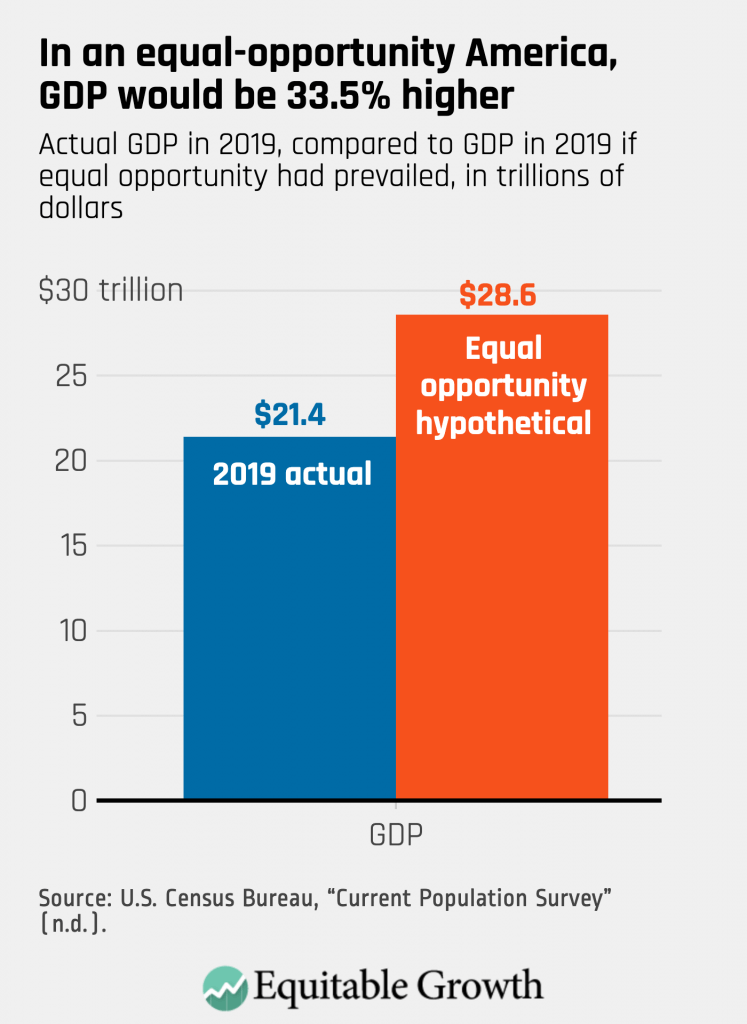

A new issue brief measures the economic costs of racial, ethnic, and gender inequities in the United States, providing estimates of the benefits of eliminating these disparities and achieving equal opportunity for all. In the brief, author Robert Lynch quantifies the significant economic costs of failing to address not only overt racism and sexism, but also discrimination in such areas as access to jobs, education, credit and loans, high-quality pre-Kindergarten, and healthcare, disparities in the justice system, disproportionate exposure to pollutants, and uneven access to quality physical infrastructure. These disparities, he continues, place heavier burdens on women and people of color. Lynch calculates the impact that equal opportunity would have had in 2019 in terms of total average earnings, Gross Domestic Product, tax revenues, the poverty rate, and Social Security solvency. While he finds significant benefits for people of color and women in eliminating U.S. racial and gender disparities, Lynch also details the gains for the economy overall, which, he notes, are even conservative estimates considering that he did not assess the benefits for non-Hispanic White males in his calculations. It might be difficult to actually realize a society that is free from disparities, he concludes, but the results would be “well worth the effort.”

Economists and economic policymakers have long debated the relationship between taxation and economic growth. These arguments sometimes rely on abstract theoretical models to prove the value of a free market economy, but empirical studies using real world data typically don’t find that increasing taxes is bad for economic growth. In an issue brief, Corey Husak examines whether recent U.S. economic history can provide evidence linking economic growth and fluctuations in the tax code—namely, in top individual income tax rates, corporate tax rates, and capital taxation. He finds that tax changes can have large effects on the U.S. economy, but these effects do not include impacts on overall economic growth or corporate investment. Husak also finds a clear correlation between lower top marginal tax rates and growing income and wealth inequality in the United States. He concludes by recommending that policymakers focus on the real, meaningful, and measurable effects of tax policy—using revenue analysis and distribution tables—rather than on economic growth as an outcome.

As policymakers in Congress debate the merits of reforming or eliminating the filibuster, new research looks into the economic and policy consequences of retaining the Senate rule as it currently stands. Nathan J. Kelly explains that by making any kind of policy change more difficult, the filibuster contributes to growing income and wealth inequality in the United States and leads to a highly unequal economy. This, he continues, is because the filibuster enhances status quo bias, which entrenches divides between the haves and have-nots in the U.S. economy by making government intervention to reduce these divides less likely. Kelly details several recent economic policies that have run up against the filibuster, from increasing the minimum wage and indexing it to inflation to implementing financial market regulations and policies centered on worker power. He then dives into a recent study he and his co-authors released that examines the distributional effects of both partisan polarization and legislative inaction, finding that the latter has a bigger impact on distributional economic outcomes. This means, Kelly concludes, that the longer the filibuster remains part of the U.S. policymaking process, the longer it will take to close income and wealth divides in the United States.

Today, the Bureau of Labor Statistics released its monthly employment report, providing data on the labor market and unemployment in the U.S. economy in June 2021. The data show that, among other things, the economy added 850,000 jobs last month, a higher-than-expected amount. Kathryn Zickuhr and Austin Clemens put together five graphs that highlight the trends in the data, while Zickuhr and Carmen Sanchez Cumming go into more detail in a column about what this Jobs Day report means for foreign-born workers in the United States. These workers already face disparities in job losses, compared to U.S.-born workers, as well as disparities in access to important income support and worker protection programs such as Unemployment Insurance and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. This, coupled with the fact that foreign-born workers are more likely to be employed in hard-hit industries during the coronavirus pandemic and recession, means foreign-born workers are disproportionately vulnerable in this economic downturn amid the ongoing public health crisis. Zickuhr and Sanchez Cumming urge policymakers to bolster and expand safety net programs rather than cut them, and to ramp up labor standards enforcement to protect workers.

Links from around the web

While racial gaps in educational attainment have narrowed over the past four decades, the Black-White wage divide hasn’t changed. In 2020, average full-time Black workers earned approximately 20 percent less than their White peers and are far less likely to have a job. The New York Times’ Eduardo Porter asks if the underlying cause of these ongoing divides is either racial bias or a changing economy. After Black Americans made strong gains in closing racial gaps at work between the 1940s and 1970s, these gains have stagnated over the past 40 years—and scholars are looking into why. Considering that Black workers today earn less than their White counterparts even relative to educational attainment, many scholars argue that race is the decisive factor in why disparities in wages and work persist. Others say industrial change, globalization, and automation have affected the economy in ways that disproportionately impacted Black workers. These questions are important because the most urgent task at hand, Porter writes, is to find a way to close the divides—and what’s causing them is key to knowing how to address them.

This summer will likely be one of the strangest ever for the U.S. labor market, writes Bloomberg’s Katia Dmitrieva. As the economy overall seems to be growing at a steady pace, millions of workers remain unwilling or unable to return to their pre-pandemic jobs, particularly in hard-hit sectors such as the retail and food-service industries. There are a number of reasons why that’s the case, whether because they want to pursue higher-paying, more stable opportunities, because they are fearful of catching COVID-19, or because they don’t have good, affordable child care options available to them. Likewise, pauses in immigration and international travel have left many seasonal jobs unfilled. Dmitrieva dives into the responses of many corporations and businesses to these trends and explains why the recovery will likely continue to look very different from previous recoveries in the coming months.

In a recent interview with The Washington Post’s Joe Heim, Mark Rank discusses poverty and the safety net in the United States. Rank explains his research on the myths of poverty in the United States, and the denial that is rampant about how much poverty actually exists in the richest country in the world. Rank also specifically calls out the need for a stronger social safety net, citing the fact that, according to his analysis, 60 percent of Americans will spend at least a year of their life in poverty. He also touches on the media’s role in portraying and reporting on poverty in the United States and how the American mindset and the myth of the American Dream play into how the general public views poverty and how much income support goes to people who are struggling. The conversation closes with his insight into how the coronavirus pandemic and recovery may parallel the Depression and resulting New Deal effort to address poverty in the United States.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “The economic benefits of equal opportunity in the United States by ending racial, ethnic, and gender disparities,” by Robert Lynch.