Weekend reading: Diversity and inclusion in economics edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Following Equitable Growth’s statement last week on the lack of diversity in the field of economics and our commitment to support more Black scholars, Equitable Growth highlighted important work from our network in the areas of incarceration, police militarization, the economic consequences of racist violence, exclusion, disenfranchisement, and reparations to address the history of oppression of Black Americans. Our colleagues and network of academics and grantees have studied the pervasive role of White supremacy in American society and politics in limiting or destroying economic opportunity for Black communities. We will use this body of work as a starting point from which to be more inclusive in our organization and push for inclusion in the economics profession as a whole. While this is a first step in elevating the research and policy ideas of diverse voices in our field, there is much more to be done.

Equitable Growth’s Amanda Fischer spoke with board member Mehrsa Baradaran in the most recent installment of Equitable Growth in Conversation. Baradaran is a leading scholar on financial services law, and her most recent book looks at the racial wealth divide in the United States. Their discussion ranged from financial inclusion and the role of Black banks in building wealth for Black communities in a segregated economy, to the different standards of responsibility that small and large businesses are held to, and why wealthy people profit off of crises while lower-income communities tend to suffer. They also spoke about the Federal Reserve’s monetary policymaking strategies and several policy ideas to make the economic recovery from the coronavirus recession more equitable.

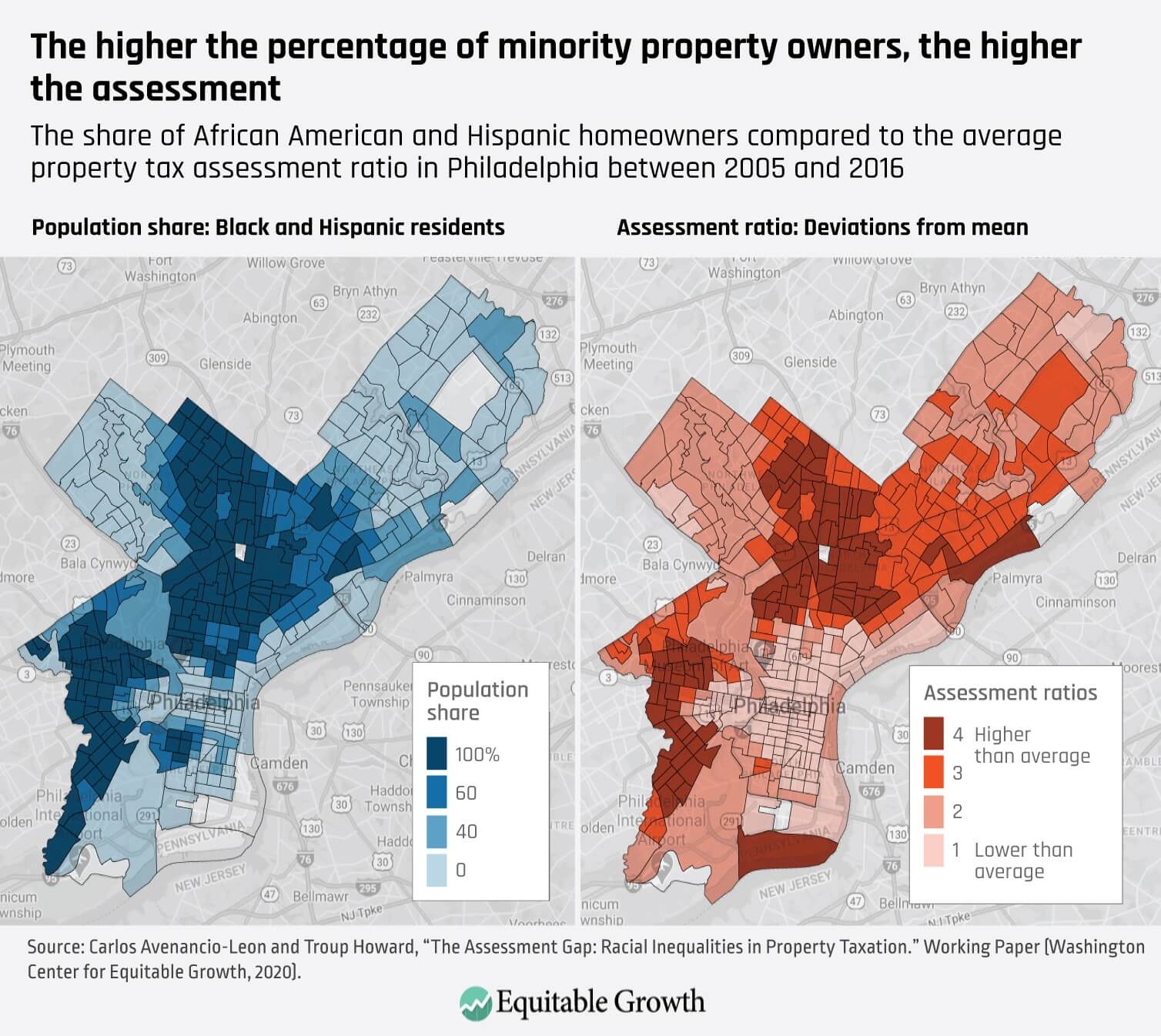

A new Equitable Growth working paper reveals that misvaluations in local property tax assessments cause the tax burden to fall more heavily on Black and Latinx households. Carlos Avenancio and Troup Howard studied market value estimations using administrative tax data and found that minority households pay 10 percent to 13 percent more in property taxes than their white counterparts living in homes of similar value in the same local property tax jurisdiction. For the median homeowner, this translates to $300 to $400 per year in additional property taxes—a significant burden, especially considering other recent research that shows that nearly 40 percent of Americans say they would struggle to handle a $400 emergency expense.

Earlier this week, Equitable Growth and The Hamilton Project co-hosted a virtual event on the coronavirus recession and the automatic stabilizers that policymakers should put in place to ensure an equitable and quick recovery. The event centered on the six policy ideas proposed in Recession Ready: Fiscal Policies to Stabilize the American Economy—a book Equitable Growth and The Hamilton Project published last year—which would automatically turn on and off depending on specific economic indicators (typically, the unemployment rate). Speakers included U.S. Rep. Don Beyer (D-VA), former chair of the president’s Council of Economic Advisers Jason Furman (a member of Equitable Growth’s Steering Committee), former Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter, Equitable Growth CEO and President Heather Boushey, and Jay Shambaugh, director of The Hamilton Project.

Links from around the web

Economics has a race problem, write Dania Francis and Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman in Newsweek. Surveys of those in the profession clearly show that Black economists feel less respected and more socially excluded, and are more likely to not apply for jobs in order to avoid discrimination and harassment. Sixty percent of Black women economists report not only experiencing gender discrimination, but also racial discrimination. And, Francis and Opoku-Agyeman continue, amid widespread protests against police brutality and anti-Black racism in the United States over the past two weeks, non-Black economists have been largely silent—“a function of their inability to confront the anti-Black racism that is embedded throughout every aspect of the discipline.” Francis and Opoku-Agyeman conclude their column with a list of three steps that non-Black individuals and economists can take to address anti-Black racism in the field of economics.

Not only does the economics profession have a race problem, but the assumptions and data that mold economic policy do as well. Racism shapes how economics is taught and practiced, writes Joelle Gamble in Dissent magazine. This means that many economic assumptions—focusing on the aggregate, for instance, instead of breaking data down to get insights about well-being—uphold racist systems by upholding measurements that are based on the economic security of White Americans. A glance at last week’s Employment Situation Report release proves this, as most headlines touted a surprising drop in unemployment while the joblessness rate among Black workers actually increased. Gamble explains how three neoclassical economics assumptions—using aggregate data to measure overall well-being, equating value with price, and considering behavior the result of independent and rational individual preferences—fail to account for racism’s influence in economics data and how racism has manifested itself in norms, institutions, and policies in the industry.

With each week that passes, the coronavirus recession is proving ever more clearly that those workers who lagged behind in the recovery from the past economic downturn are being hit harder during this one. Familiar patterns are reappearing: Black and Latinx workers continue to lose their jobs more often and for longer periods of time and are having more difficulty getting government support, write Patricia Cohen and Ben Casselman in The New York Times—and they have less of a financial cushion thanks to the racial wealth divide. Even owning a business or being self-employed hasn’t protected African Americans from suffering more during the pandemic—and, report Cohen and Casselman, some are concerned that the almost-inevitable cuts coming in state and local government jobs will disproportionately harm Black middle class families as well.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Misvaluations in local property tax assessments cause the tax burden to fall more heavily on Black, Latinx homeowners” by Carlos Avenancio and Troup Howard.