Weekend reading: Data amid the coronavirus recession edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

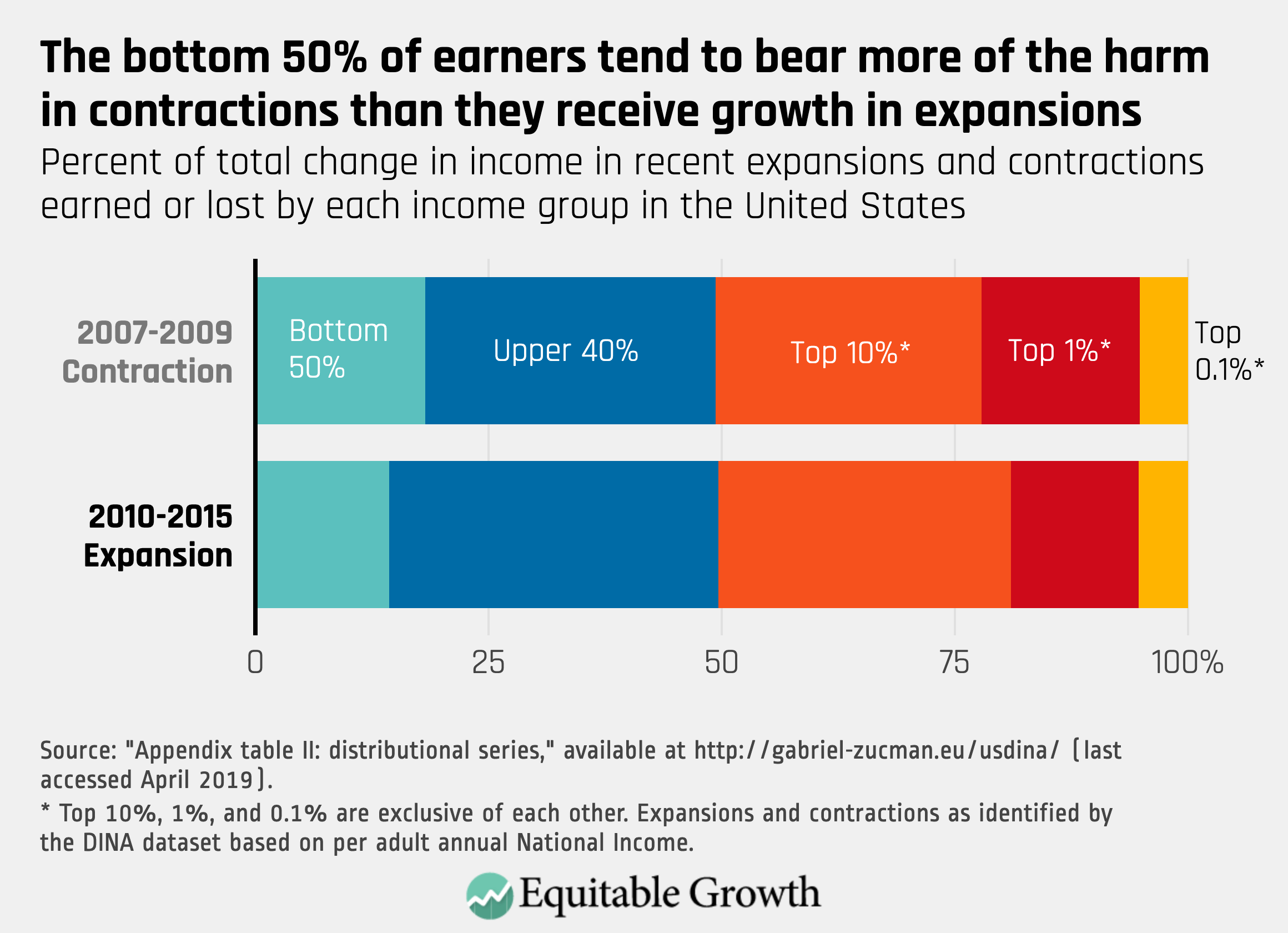

The U.S. economy is a long way away from recovering from the coronavirus recession, which will likely be long and bumpy when it does happen. But now is the time to ensure policymakers have the data they need to effectively help those who are hurting the most and will continue to hurt long after the crisis passes. Policymakers must ensure they are measuring how the economy is working for low-, middle-, and high-income Americans. Austin Clemens explains how a new dataset from the U.S. Bureau of Economic analysis divides up annual income growth along these lines and why this is an important step in targeting aid to those who need it the most. It’s especially important to consider, Clemens writes, because those at the bottom of the income ladder have continually experienced far less of the gains of past economic recoveries than their better-off peers—even after also being hit harder during the economic downturns that preceded the recoveries. Policymakers can use data to ensure a more fair recovery that benefits all Americans, not just the wealthiest of our society.

Likewise, Heather Boushey writes on Medium, the only way policymakers will be able to measure whether the relief packages they have passed are actually working is by collecting accurate data about how Americans along the income ladder are faring. The imperative to collect these data is included in the fourth coronavirus package proposed recently by Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi (D-CA), and is grounded in our GDP 2.0 project. It would be an important tool in tracking whether other relief actions—from expanded Unemployment Insurance to small business funding to relief payments sent to households across the United States—are effectively shaping an economy where gains and losses are shared equally among the population. Looking at the historical example of when Gross Domestic Product was first unveiled, Boushey shows why income inequality has rendered GDP ineffective as a barometer of overall economic growth, and why it must be broken down to include data across the income spectrum.

Effective data collection not only can guide policymakers as they take action to help those in need but also provide a level of transparency that is much-needed to shore up trust in public institutions among the American people. Amanda Fischer reviews the lessons policymakers can and should learn from the Great Recession of 2007–2009, when a lack of data all but ensured that relief was more delayed and ineffective than it would have been had policymakers properly collected data. As Congress passes trillions of dollars of coronavirus-related economic relief aimed at shoring up various sectors of the economy and protecting hard-working and hard-hit families, Fischer writes, policymakers must also release accurate data so that the public can hold government accountable about how it is spending and distributing this taxpayer money.

In the latest installment of “Equitable Growth in Conversation,” Liz Hipple talks with Trevon Logan, the Hazel C. Youngberg Trustees Distinguished Professor of economics at The Ohio State University and a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research, about disproportionate impact on black Americans of the coronavirus pandemic and ensuing recession, the structural inequalities that led to these disparities, and the historical legacy of intergenerational mobility, race, and segregation. They also discuss policy recommendations to address the coronavirus recession and to deal with structural inequalities in society.

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, previously known as food stamps, is a vital part of the country’s social safety net. It not only keeps people fed and healthy, but also can help stabilize the U.S. macroeconomy by boosting consumer spending even when household budgets are otherwise limited—which is why some legislators have recently proposed using SNAP as an automatic stabilizer during economic downturns. New research by Martha Bailey, Hilary Hoynes, Maya Rossin-Slater, and Reed Walker shows that even as SNAP’s economic and health benefits play an important role during hard times, they also have long-lasting effects far into the future, for recipients as well as the broader economy. The co-authors explain the methodology, findings, and implications of their new working paper and urge Congress to enact enhancements of this vital program now, as the coronavirus recession threatens households across the country.

Links from around the web

In another item for the “GDP needs an update” category, Justin Wolfers argues in The New York Times that the official measure of the U.S. economy should be incorporating our social distancing efforts. The sacrifice of millions who are staying home to “flatten the curve” is saving countless lives, so why isn’t this effort being counted? The answer is because “the official measure of [GDP] takes a much more limited view of what counts as ‘output,’ and it hides this progress,” Wolfers writes. The true value of what we have done in the past few months is probably higher than it has ever been, he continues, but failing to measure these public health precautions has led to a misdiagnosis of our economic situation—and thus a misleading conversation on when and whether to reopen the economy.

The data released last week by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics show how the 14.7 percent unemployment rate is affecting different groups of workers differently. Tracy Jan put together a series of graphics for The Washington Post using the data to show how the coronavirus recession has been distributed across the U.S. population, making clear that age, gender, educational attainment, and race are obvious dividing lines in the joblessness rate. Jan’s analysis highlights that young workers, women, those without high-school degrees, and Hispanic and black workers are faring the worst in the worst economic situation since the Great Depression.

Many millennial workers were still recovering from effects of the Great Recession when the coronavirus pandemic began, and this group of younger workers is likely to suffer the worst from the coronavirus recession as well. Vox’s Sean Collins explains why the COVID-19 economy is particularly devastating for millennials, who entered the workforce during one of the worst downturns in recent history and are now facing a second battering right when they should be earning their career peak salaries. In a series of 14 charts, Collins shows why everything from layoffs to student debt to lower rates of homeownership have hit millennials harder than other generations in the workforce, and how these factors lead younger workers to worry more about their current and future standings in the economy.

Essential workers—from grocery store clerks, warehouse workers, and childcare providers to delivery people, home health aides, and farmworkers—are currently risking their lives to make sure the rest of us are healthy, fed, cared for, and living in a functioning society. So, The Atlantic’s Annie Lowrey asks, why are these modern-day heroes treated so poorly and paid so little? The answer is not because these jobs are worth less to our economy than others, but rather because of “the kinds of people who hold them and the kinds of labor laws we have chosen. They are bad jobs because we have not cared to make them good jobs.” Now, these workers are risking more than ever before to protect and support the rest of us, and so now is the time for change, Lowrey argues. Policies such as higher minimum wages and mandated paid sick leave, and encouraging unionization or expanding labor regulations could go a long way in showing these workers how vital they truly are.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Data will provide accountability to ensure the U.S. economic recovery is shared broadly” by Austin Clemens.