Weekend reading: “Corporate Responsibility” edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week, and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

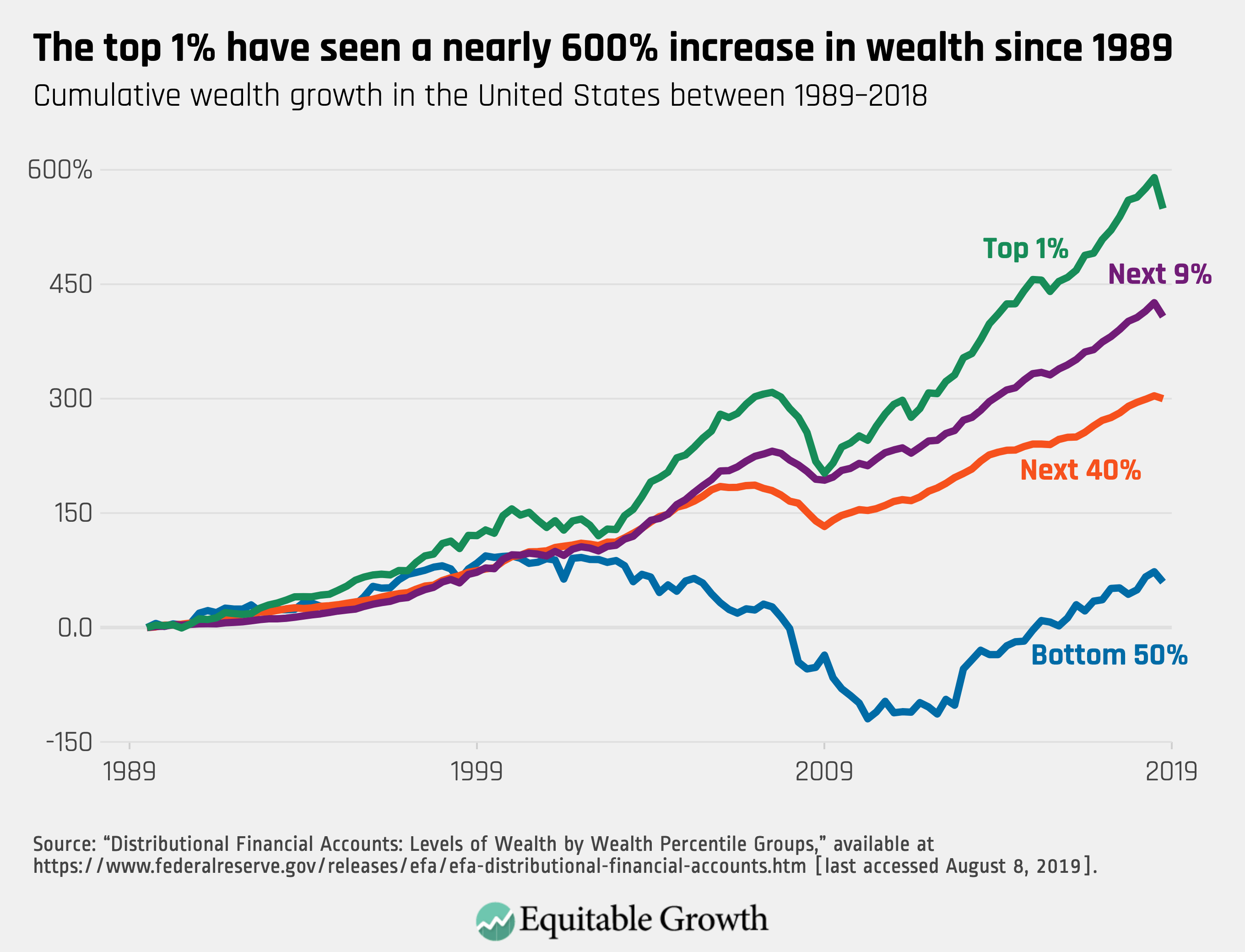

Wealth disparities between the rich and the poor in the United States have broadened over the past 30 years, according to the Federal Reserve Board’s Distributional Financial Accounts, released earlier this month. Raksha Kopparam analyzes the new data, which show that the bottom 50 percent of wealth owners in the United States are only now returning to the levels of wealth they had in 2000, and that their share of the nation’s wealth is glancingly small. At the other end of the spectrum, the top 1 percent have seen their wealth grow by 600 percent since 1989.

The domestic outsourcing of jobs in the United States is fast becoming a dominant explanation for the destruction of the social contract of work, a historic concept in which norms of fairness and solidarity between firms and their employees played a major role in wage setting and workplace standards for some U.S. workers—though of course many others such as African American workers were consistently more marginalized. Kate Bahn reviews relevant research literature from a wide array of sources, including Equitable Growth, and finds that the U.S. labor market is increasingly characterized by the fissured workplace, in which workers are employed at firms with core competencies and all other duties or certain functions in the production process are contracted out, and, not coincidentally, by monopsony, the ability of firms rather than markets to set wages. These trends, she notes, are at least partly responsible for stagnant wages and declining job quality.

The United States remains the only industrialized nation without a national paid leave program, despite evidence that these programs can benefit working parents and employers as well. In 2004, California became the first of what are now eight states, plus the District of Columbia, to establish a publicly funded program for family leave. Katherine Policelli and Alix Gould-Werth report this week on new research by Alexandra Stanczyk showing that California’s paid leave program helped new mothers avoid poverty. “The introduction of paid leave in California,” they write, “is tied to a 10.2 percent decrease in risk of new mothers dropping below the poverty threshold and disproportionately helps women with lower levels of education and who are unmarried.”

Brad DeLong has again passed along his worthy reads for the past week or so, with content from Equitable Growth and elsewhere.

Links from around the web

This week, the influential Business Roundtable, whose members are the chief executive officers of nearly 200 of the largest corporations in the United States, issued a statement declaring that maximizing profits for shareholders should no longer be the sole purpose of a company. The statement declares that the concerns of other stakeholders—workers, consumers, suppliers, and communities—also need to be corporate priorities. In a column published later in the week, Eric Posner, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School, expresses some skepticism. “While the statement is a welcome repudiation of a highly influential but spurious theory of corporate responsibility,” he writes, “this new philosophy will not likely change the way corporations behave. The only way to force corporations to act in the public interest is to subject them to legal regulation.” [atlantic]

“Most Americans say it’s not ideal for a child to be raised by two working parents,” writes The New York Times’ Claire Cain Miller. “Yet in two-thirds of American families, both parents work. This disconnect between ideals and reality helps explain why the United States has been so resistant to universal public child care. Even as child care is setting up to be an issue in the presidential campaign, a more basic question has recently resurfaced: whether mothers should work in the first place.” Miller adds: “…[I]n the United States, people have long had conflicted feelings about whether society and government should make it easier for mothers to work outside the home, and these are complicated by attitudes about race and poverty.” [nyt]

German Lopez was skeptical of unions. Then, the Vox senior correspondent joined one. He describes how he went, in a year and a half, from opposing the unionization of the Vox Media editorial staff to celebrating with his colleagues when the union signed a contract agreement with the company. He explains that he was not opposed to unions in general but thought Vox was a generous company, and that some workers would take advantage of union protections. But after he did the research, which he describes in this piece, he was sold, not only on the Vox union but on the deep importance of unions for all workers. “I had done a complete 180 on unions,” he writes. [vox]

“You have a better chance of achieving ‘the American dream’ in Canada than in America” may be a startling headline, but the data don’t lie, former Equitable Growth Steering Committee member Raj Chetty tells Ezra Klein in a one-on-one interview. Chetty discusses his recent research on families, neighborhoods, and mobility; on the significant return on public investments in children; on the impact of poverty on life expectancy; and on the “fading of the American dream,” the expectation that children will be better off than their parents. [vox] (See also Equitable Growth’s In Conversation with Raj Chetty.)

We tend to think of doctors as having very long, sometimes erratic hours, which can be another way of saying family-unfriendly hours. But Claire Cain Miller, in another interesting analysis, finds that things have changed. “Medicine has become something of a stealth family-friendly profession, at a time when other professions are growing more greedy about employees’ time,” she writes. “[M]edicine has changed in ways that offer doctors and other health care workers the option of more control over their hours, depending on the specialty and job they choose, while still practicing at the top of their training and being paid proportionately.” And Miller cites Claudia Goldin’s research showing female doctors are likelier than women with law degrees, business degrees or doctorates to have children. Other research shows they’re also much less likely to stop working when they do. [nyt]

Friday Figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “The Federal Reserve’s new Distributional Financial Accounts provide telling data on growing U.S. wealth and income inequality,” by Raksha Kopparam.