U.S. labor markets require a new approach to higher education

This essay is part of Boosting Wages for U.S. Workers in the New Economy, a compilation of 10 essays from leading economic thinkers who explore alternative policies for boosting wages and living standards, rooted in different structures that contribute to stagnant and unequal wages. The authors in the new book demonstrate that efforts to improve workers’ access to good jobs do not need to be limited to traditional labor policy. Policies relating to macroeconomics, to social services, and to market concentration also have direct relevance to wage levels and inequality, and can be useful tools for addressing them.

To read more about Boosting Wages for U.S. Workers in the New Economy 20 and download the full collection of essays, click here.

Overview

In February 2020, the longest economic expansion on record since 1854 ended. During the expansion, a concerning trend that began in the 1970s continued—the proliferation of low-wage, low-quality jobs and the decline of middle-wage jobs. The rise of these low-wage, low-quality jobs is only one signal of a struggling U.S. economy. New economic arrangements driven by supply-side economic policies, globalization, and technological change led to greater divide along dimensions of income and wealth, race, and geography over the past five decades.

As the third decade of the 21st century begins, concerted efforts are needed to transform the U.S. economy into one that provides all Americans with opportunities for social and economic advancement, stems the tide of growing inequality, supplies the labor market with skillful, agile, and knowledgeable workers, and broadens the scale and scope of jobs being created. Government policies that shape the underlying structures of our economy to foster these outcomes will address one of the most common concerns of all Americans—boosting wage growth so people are able to share in the rewards of a vibrant economy and build the wealth they and their families need to secure future prosperity for themselves and the nation.

No other services industry occupies a more strategic position than higher education to achieve these goals. This essay provides evidence-backed analysis for targeted higher education policies aimed at boosting wages and jobs growth across the nation.

Higher education plays a key role in both the cyclical and structural aspects of the U.S. labor market. Institutions of higher learning shape and supply skilled labor to the economy. They absorb excess workers in low-income jobs from the labor market by providing a productive alternative to work and by providing opportunities for future advancement. They contribute to the research, development, and dissemination of productivity-enhancing knowledge, which expands the scope of jobs created in the economy, and they are direct sources of good jobs in many localities. By ensuring that workers up and down the income ladder have options in the labor market and opportunities for advancement, a democratic higher education system increases bargaining power of workers while providing among the highest returns on investment in a public policymaker’s toolkit.1

Higher education is a good with unquantifiable positive externalities that accrue to large swaths of society, even those who do not participate directly. At the same time, the quantifiable fiscal rate of return for investment in higher education is positive and large. Total government spending per college degree over a college graduate’s lifetime is actually negative, meaning that the government receives more in tax revenue minus benefits from a college graduate. The average real fiscal rate of return on government investment in college students is conservatively estimated to be more than 25 percent.2 And this doesn’t include the many social returns to college attainment such as extra productivity, greater job creation, lower likelihood of crime and incarceration, higher civic participation, and the spillover effects of all these factors to the next generation of American workers.

This essay makes the case for a renewed public investment in higher education. First, I examine the socioeconomic problems confronting higher education in the United States today and the free-market, supply-side ideological reasons for these problems. I then highlight the historic higher education reforms of the 19th and 20th centuries—most famously, government investments in land grant colleges and universities to boost more equitable regional economic growth and the landmark GI Bill that still provides tuition and income support for veterans who seek higher education opportunities.

The essay concludes with a set of reform proposals for higher education based on a new round of robust investment and complementary policies that would:

- Set economic signals and incentives for higher education that broaden job opportunities and boost broad-based wage growth in the U.S. economy

- Boost public investments in regional research and development to ensure these public investments result in nationwide prosperity for all students, especially low-income students and students of color

- Expand postsecondary school admissions, learning, and attainment of degrees to create educational pathways that generate new jobs and new services and industries needed in a productive U.S. economy in the 21st century

The socioeconomic problems confronting U.S. higher education

The most recognizable role of higher education in the debate over sluggish wage growth in the United States is that investments in higher education deliver high labor market returns far into the future for most graduates. Yet the returns to higher education are not equitably distributed, and policy choices within higher education have intersected with other structural inequalities in the U.S. labor market to further entrench income and wealth inequality.

The globalization of the labor market and technological change are understood to be reasons for the steady disappearance of good middle-wage employment opportunities and the rise of low-wage, low-quality jobs. The economic argument was that the winners who gained from the new economic arrangements would compensate the losers through public investment in education and training. The idea was that individuals who were displaced would retrain and join expanding, new, and more productive sectors of the economy, and everyone would share in the gains from technology and globalization.

But instead of bolstering higher education, funding sources for higher education declined on a per-capita basis, and the federal government offered loans instead of grants to college students. Record increases in tuition fees beginning in the 1980s gradually but inexorably shifted the heavier burden of paying for college from the government to individuals and their families, who carry a fast-growing $1.7 trillion student loan balance.

Today, many public universities that perform the best in terms of moving individuals up the economic ladder are increasingly out of reach for average low-income students and students of color.3 Just 30 percent of children born to families in the bottom quarter of the income distribution are expected to enroll in college today, compared to 80 percent from the top quarter, and high-income individuals are six times more likely to complete a college degree.4

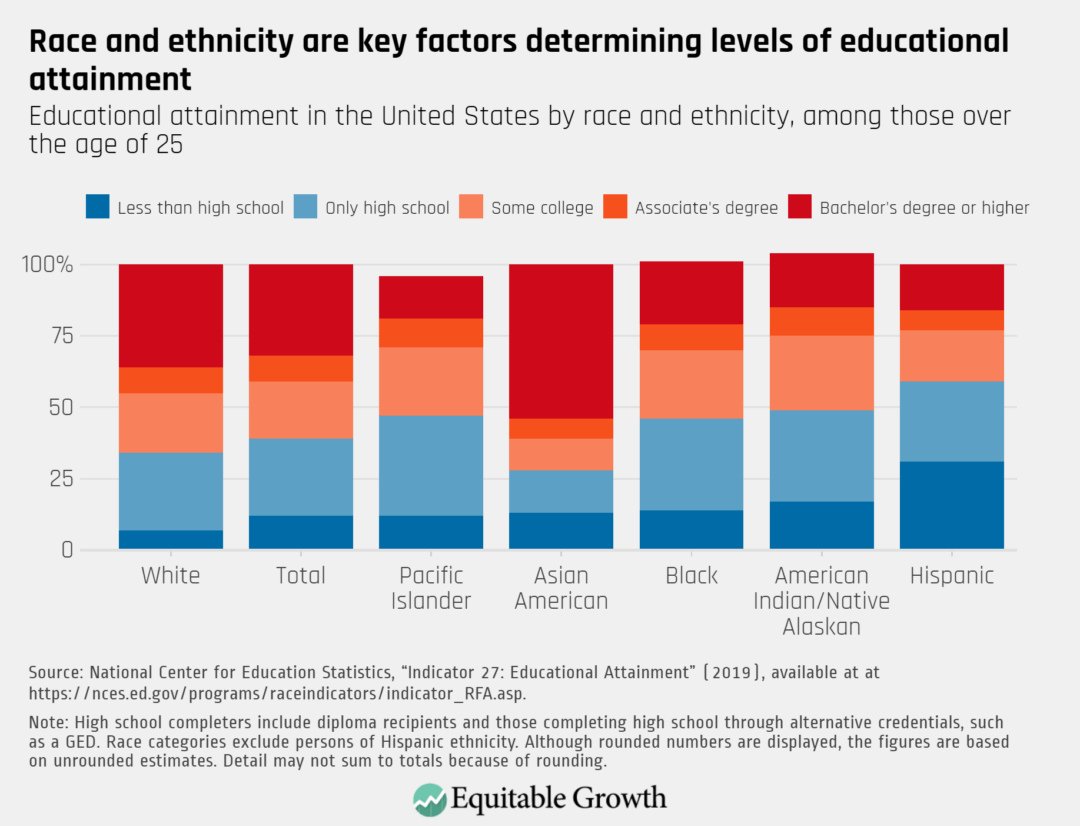

The failed potential of higher education is also reflected across race and ethnicity. Attaining a bachelor’s degree varies from a high of 54 percent for Asian American college students to a low of 28 percent for American Indian and Native Alaskan students. The average for all students over the age of 25 is just 32 percent, showing there is much room for improvement. The lower educational attainment among workers of color may be able to explain some of the increasing dominance of low-wage jobs for this group.5 Indeed, the prevalence of the “some college, no degree” category suggests that many students are interested in a college degree but are having trouble completing college. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

But a college degree by itself is not enough. The racial wage divide persists at higher levels of educational attainment, with Black and Latinx workers with college degrees earning lower wages than White workers with college degrees.6 In addition to inequitable access to the best universities, the failure of the economy to produce a broad scope of jobs that college graduates can fill and the currently weak state of worker power in the United States mean that many workers who already have college degrees are not fully seeing the returns to that investment.

There are a number of other reasons why the once-prevailing idea that investments in higher education were a ticket up the economic ladder did not endure. Specifically:

- Returns to investment in research, development, and experimentation are not fully realized.

- Local area economic benefits of universities are not fully pursued.

- The immediate effects of university enrollment on labor market outcomes are not fully pursued.

Let’s examine each of these reasons in turn.

Returns to investment in research, development, and experimentation are not fully realized

There is considerable evidence of the economic benefits of public research and development activities, which are crucial for the innovative capacity of the economy.7 Exploration and experimentation are integral to the discovery process. But with students bearing the high cost of college, exploration and experimentation in learning becomes riskier. Students are understandably choosing majors that have immediate market payoffs. Universities are responding to “market demand” and a decline in funding by reducing course offerings and eliminating different majors and minors.8 This limits the range of options for study for students, limiting them to careers that are already available instead of encouraging creation of new industries.

Indeed, there is evidence that technological advancement tends to complement the skills of workers.9 A lower proportion of skilled workers and a smaller range in the skills of workers implies a small market size and a more limited scope for skill-complementary technologies. This, in turn, reduces the dynamism and innovative capacity of the economy and decreases the scope of jobs that the economy can create. This skill-complementarity in technological change also leads to inequality in income for skilled versus “unskilled” workers.

Then, there are the race, gender, and socioeconomic divides in the science, technology, engineering, and math, or STEM, fields. STEM degrees are plagued by the lack of representation that places even more limitations on the range of job options available to poor students, women, and students of color.10 Additionally, the focus on STEM fields must be combined with renewed investment in the humanities, social sciences, and other disciplines. With the fast pace of technological change, students need a broad-based education that prepares them to counter some of the social challenges created by technology, while also preparing them to be agile workers who can adjust to a fast-changing world.

Local area economic benefits of universities are not fully pursued

Universities and university-affiliated medical centers are among the largest employers in many cities. In the United States, higher education institutions employed approximately 4 million workers in 2018 as faculty, staff, and administrators.11 That is more than 78,000 jobs per state, on average. The shrinking of the higher education sector and increased focus on cost efficiencies such as employing qualified instructors in precarious, low-paid, contract-based appointments are eliminating decent jobs at the same time that states and localities are looking for ways to increase the number of good jobs. There are concerns about the impact of the coronavirus pandemic and COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus, on these employment numbers. As of October 2020, employment at public higher education institutions was down by close to 14 percent.12

Studies consistently show the positive spillovers from universities into the local and regional economy. Proximity to a university is often associated with recent growth of high-tech industries and local economic and job growth in the same county as the university, as well as nearby areas.13 Yet funding for research and development in the United States is very unequal geographically. Given the localized nature of these returns to investment in higher education, localities without a research facility may be disadvantaged.

The immediate effects of university enrollment on U.S. labor market outcomes are not fully appreciated

Higher education plays an important role in reducing surplus labor in low-wage sectors of the U.S. economy, especially among young adults. Labor force participation is low among young adults, yet their underutilization in the labor market is very high. Many of these young people are often unable to find a job, so postsecondary enrollment is integral to their human capital preservation and accumulation.

Without this labor-absorbing role, there also is a higher likelihood that young people will have greater involvement with the race-biased U.S. criminal justice system, which further leads to poorer employment outcomes in the future, particularly for young people of color.14 This is not only true for young adults. About 16 percent of full-time students and 40 percent of part-time students at undergraduate institutions were over 25 years old.15

It is likely that the high price of higher education puts downward pressure on wages by keeping many who would be in college in an already-saturated low-wage labor force. The premise of this hypothesis is predicated on the high prevalence of work among college-goers. Approximately 80 percent of part-time students and 50 percent of full-time college students are employed while completing their undergraduate education.16 This places work and education in competition for these workers’ time.

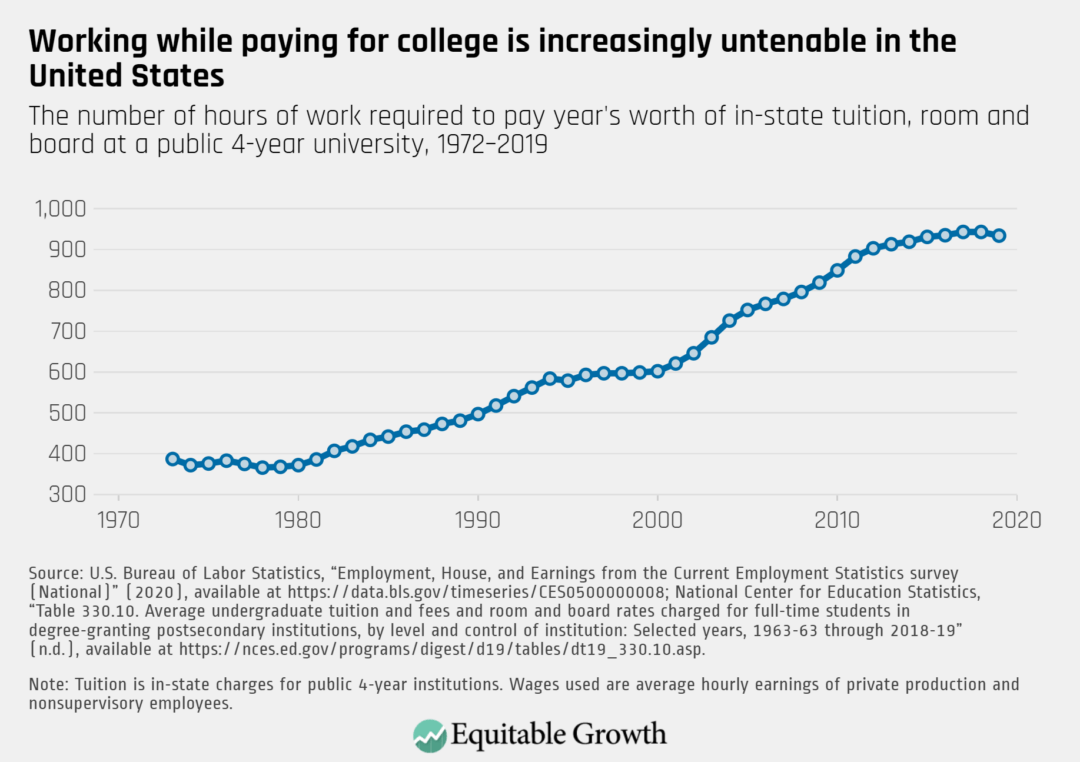

The slow rate of wage growth combined with high-tuition growth means the amount of work required to fund college is rising. In the 1970s, the typical student would need to work approximately 400 hours in order to pay a year’s worth of tuition at a public 4-year college. This is equivalent to 10 weeks of full-time, 40-hours-a-week employment, something that could be done during the summer months. Today, a typical low-wage worker would need to work close to 1,000 hours to afford the cost of tuition. That is equivalent to 25 weeks of full-time, 40-hours-a-week employment, almost half a year of work with little time to study.

Figure 2

Many low-income students receive substantial tuition discounts. But low-income students also generally possess less information and make enrollment decisions based on sticker prices. That’s why lower sticker-price tuitions could encourage more investments in college education among low-wage workers, while also boosting wage growth at the low end of the labor market by decreasing the labor supply of student-workers while in college.

To illustrate this point, consider that in 2018, there were about 17 million undergraduate students, with close to 60 percent of them working at some point while studying. Assume tuition rates declined to zero. Many of these working students would choose to study instead, decreasing the supply of labor in low-wage jobs. Then, assume 50 percent of currently working students would choose to study full time or increase their study hours. That would mean close to 7 million students reducing their supply of labor.

Consider then that there are about 53 million workers classified as low-wage workers.17 This translates into a 13.6 percent decline in the supply of labor in low-wage jobs. This would have a positive effect on wages, directly benefiting workers who remain in these heretofore low-wage sectors of the economy.

To test this hypothesis, I model the relationship between the rate of tuition growth at public institutions and wage growth at the national level between 1972 and 2019 and across states and the District of Columbia since 2004 using a combination of data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, and the National Center for Education Statistics. I also look at other relationships among higher education and the labor market, including the effects of tuition growth on labor force participation, weekly hours worked and employment rates, and the relationship between enrollment rates and wage growth.

After controlling for variables that affect both tuition and wage growth, such as the unemployment rate, I find a negative and statistically significant relationship between tuition at public institutions and wage growth. I find that a 1 percentage point increase in public 4-year tuition growth is associated with a 0.485 percentage point reduction in wage growth for private nonsupervisory workers, a 0.46 percentage point reduction for retail workers, and 0.58 percentage point reduction for hospitality workers.

Hours of work per week is also related to tuition growth. In this case, I find that a 1 percentage point increase in 4-year tuition is associated with a 0.06 percentage point increase in hours worked per week. The relationship between tuition growth and labor force participation is also mostly positive, but not statistically significant. Since higher tuition and lower wages occur together, it is possible that some people leave the labor force altogether (due to low wages) while others enter the labor force (to pay for higher tuition costs), and these two effects offset each other.

I also estimate the relationship between changes in the college enrollment rate over time and changes in the wage rate. I find that increases in the college enrollment rate are associated with a 0.39 percentage point increase in hourly earnings for private workers, a 0.28 percentage point increase for retail workers, and a 0.44 percentage point increase for leisure and hospitality workers. All of these patterns hold with slight differences in the magnitude of the effects when looking at the state level over time and with a lag of 2–3 years.

While causal effects can never be claimed with certainty, the patterns of these relationships support the hypothesis that lower sticker-price tuition and higher college enrollment rates would reduce the labor supply in low-wage sectors of the U.S. economy and thus place upward pressure on wages. Other research supports this labor-supply, wage-growth hypothesis, finding that a percentage point increase in the supply of college graduates raises wages for high school drop-outs by 1.9 percent and for high school graduates by 1.6 percent, although some of this effect is due to positive spillovers.18

Additionally, the negative relationship between real tuition and real wage growth means periods of high tuition growth, when students most need higher wages to offset the increase in tuition, are precisely when wage growth is at its lowest. And since low-wage jobs usually bear negative qualities such as unpredictable scheduling and fewer accommodations such as time off with pay, it is even more likely that students will drop out of school. The lowest-income individuals are stuck in a low-wage, high-tuition trap, where they need higher wages in order to afford college and they need a college degree to attain higher wages. This makes it harder for these individuals to move up the income ladder.

Policy proposals to reform higher education

The problems outlined above suggest a role for policy to reform higher education in the United States. The proposed policy reforms could increase the educational attainment of the labor force. Policies could boost investment in higher education by placing emphasis on outcomes based on family income, race, and geography. Policies could encourage exploration and experimentation in research and areas of study to expand the scope of these endeavors. And polices could increase options for low-wage workers who would also like to study. A focus on all of these measures aligned with the broader goals of improved welfare for all could form the basis of a new higher education focus that creates a more equitable U.S. labor market and equitable economic growth and prosperity.

These higher education policy reforms would cascade across a number of policy domains and include an array of potential policy instruments. And they would require a different level of decision-making and action to effectively target the problems outlined. Specifically, policymakers would need to:

- Set economic signals and incentives

- Boost research and development across geographic regions and underserved groups

- Expand postsecondary school admissions, learning, and attainment of degrees

I’ll examine each of these steps in turn.

Set economic signals and incentives

The cost of higher education is usually one of the first things families consider when deciding whether a student should apply to college and where to go. A tuition-free model signals a public commitment to higher education and relieves other constraints on students, such as the need to rely on debt or to spend large amounts of time working in order to afford school. Evidence from promise programs around the country shows a host of positive outcomes for students when the cost of attendance is removed, including greater likelihood of completing the degree and better performance at lower levels in the education pipeline.19

A study from researchers at University of Michigan, for example, shows that even a sticker price of listed tuition for students who would qualify for financial aid that reduces their balance to zero still discouraged those students from applying.20 Tuition-free for all is also important to get public support and buy-in. Other economic incentives that could encourage individual investments in postsecondary education include subsidies for going to college. This would allow public support to cover the opportunity cost of college, which includes lost income from not working. This again would signify that human capital investments are important labor market activities, especially to low-income youths who tend to have low labor force participation.

Cancelling current student debt is another policy option. This action would not only encourage some of the large number of individuals in the labor market with “no college, some degree” to finish their college educations but also ease the disproportionate burden of student debt on low-income students and students of color. A debt- and a tuition-free model would remove some of the economic distortions such as debt-fueled increases in tuition, predatory for-profit institutions that use students to tap into student loan funds, a shifting away from public-service careers by college graduates, and informational barriers for low-income students.

There are many lessons that can be learned from the administration of the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, better known as the GI Bill, that can be extended here. Lessons including handling the distribution of tuition benefits, encouraging advancement toward degrees, covering the cost of training for specific careers, industries, or trades, co-op training or work-study, correspondence training, and distance learning. A crucial lesson from the GI Bill is that policies must center equity in their designs. The GI Bill fostered economic mobility for recipients, but increased the racial attainment gap because it was administered by the states, which systemically shut out Black veterans.21

Boost research and development across geographic regions and underserved groups

The Morrill Act of 1862 that established land-grant institutions successfully demonstrated that higher education was not just for the children of elites, but that students from poor families also can do well if given the opportunity. But this first act did not provide the same opportunities for Black Americans. The second Morrill Act in 1890 attempted to rectify this inequity with the establishment of institutions for Black Americans.

The United States currently spends a substantial amount of money on research and development. But this spending is extremely skewed by geographic region and by institution. Like the second Morrill Act, a new act is needed in the area of research and development in higher education that increases research incentives to currently underfunded areas, such as historically Black colleges and universities, other institutions serving people of color, technical postsecondary institutes, and underserved geographic locations. This proposal is one way to direct productive funds to struggling HBCUs, improving racial equity and access in the higher education sector and bringing left-behind geographic regions into the knowledge-based economy.

One way of potentially enhancing local economic conditions is to establish research centers housed at colleges and universities around the country in locations that have low research activity. These localized research centers should help localities and institutions serving people of color to identify or create new comparative advantages and identify the most binding constraints to job creation, human flourishing, and other factors relevant to those region and constituents.

This localized research hub proposal is similar to one put forth recently by economists Jonathan Gruber at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Simon Johnson at the MIT Sloan School of Management.22 Another similar example is the creation of manufacturing hubs by former President Barack Obama in Youngstown, Ohio and 11 other localities left behind by globalization.23 This time, however, the focus would be on research hubs. These research hubs would be staffed by the expected increase in enrolled students and postsecondary educators should policymakers move toward free college tuition and student-debt reform.

There are other, more distant but historically successful programs to boost regional research and development institutions that policymakers could look to for inspiration. One is implementation of the Hatch Act of 1887, which, among other things, allocated funds to public land grant colleges and universities to further develop agricultural and experimental research centers. Another is the Smith-Lever Act of 1914, which established programs designed to apply laboratory research findings to the farms, households, and businesses within local communities.24

These types of location-based efforts could work in tandem with other types of cluster policies such as enterprise zones. Private industry could also partner with institutions to share advice, provide technical training, supply trained students, and apply research findings to business practices. In this way, local governments, local firms, and local universities (including students) would work together to make decisions about these initiatives.

Expand postsecondary school admissions, learning, and the attainment of degrees

Decision-making in this domain of higher education mainly operates at the student and university level, but state and federal policies affect these outcomes. Public education institutions, for example, generally respond to declines in appropriations and funding by increasing tuition and by increasing admissions of wealthier students, out-of-state students, and international students, who pay higher prices at the expense of poorer students in a state. As a result, access to the best public universities are increasingly based on ability-to-pay, which goes against the belief of Sen. Justin Smith Morrill of Vermont (of the Morrill Act of 1862 or the Land-grant Act) that higher education should “be accessible to all, but especially to the sons of toil.”25

These tuition decisions also usually result in less college access for students of color, many of whom are more likely to be poor. That’s why affirmative admissions policies that foster more equitable access for all students should be pursued. In addition to more equitable admissions policy at every institution of higher learning, funding for the expansion of educational capacity at HBCUs and institutions serving people of color are integral. HBCUs, which make up just 3 percent of colleges and universities, produce 27 percent of African American students with bachelor’s degrees in STEM fields and confer one-fourth of the bachelor’s degrees in education awarded to African Americans. One HBCU, Xavier University, awards more undergraduate degrees in the biological and physical sciences to Black students than any other university in the nation.26

The new funding model of free or reduced costs of college tuition would relieve students and universities from viewing areas of study simply as job training with immediate payoffs. And it would encourage more exploration among college students of the factors in their education they think play best to their talents, interests, and potential future payoffs. Students at all types of postsecondary institutions also would be able to engage in other foresight exercises during their training, such as identifying research priorities for local, regional, and national economic development.

This would allow students to help design the future economy that they will inhabit, for example, by choosing majors and research activities geared toward sustainability, climate, and energy conservation, equity, and human flourishing. This creates a richer student experience that includes paid research activities so students are engaged in relevant job experience while they study.

Universities will need to be flexible in offering subject areas, independent studies, and time commitments to accommodate student exploration. There should also be an emphasis on college attainment through incentives and student support services. The disinvestment in the higher education faculty workforce that led to reliance on contingent faculty, unpaid administrative positions, and adjunctification would need to be reversed. This would not only increase the needed manpower to meet expected growing demand for college attainment, but also will restore a direct source of good jobs in the economy.

Conclusion

The higher education policy reforms proposed in this essay should not be isolated from other policy priorities to boost wage growth and job opportunities in the U.S. economy. Rather, these higher education policy proposals should be merged with ongoing innovation policy and policies targeting green industries and clean technologies, from research and development in the student’s curriculum to job training in those industries.

This new educational focus could be built up and supported by education policies for primary and secondary schools, as well as at the pre-Kindergarten and Kindergarten school levels. Mapping new and innovative education policies across the next generational arc would serve our nation well in the 21st century.

Similarly, higher education reforms also could be combined with job guarantee proposals, where graduates of higher education could be placed in social services or public-good industries around the country. And these policies could be combined with ones that bolster labor standards and strengthen worker power. A focus on human capability, worker power, and broad scope of innovation are policies that will move the economy in the right direction, and higher education has an important role in this new trajectory.

All of these proposed reforms build on the historic successes of higher education investments in boosting regional economic development, job creation, and national innovation. The Morrill Act of 1862 established land grant colleges and universities. The second Morrill Act of 1890 established 17 historically black colleges and universities.27 The Hatch Act of 1887 and the Smith-Lever Act of 1914 explicitly expanded the role of these schools in local and regional economic development and job training. And then, there’s the GI Bill, which provided veterans with college tuition and room and board benefits, and the Higher Education Act of 1965, which provided aid to students around the country.

Many promising programs around the country and tuition-free models demonstrate the transformative role of broad access to higher education for individuals and society. These and other higher education policies and programs are the bedrock upon which to build the future role of higher education in our nation’s economy in the 21st century. Crucially, all of these historically successful higher education reforms and the ones proposed in this essay share a common strategy—public investment in pursuit of the common good.

In contrast, the lessons learned about the failures of higher education policies to boost wage growth and jobs growth—policies based almost solely on free-market, supply-side economic theories—are now clearly evident. The historic economic expansion post-2008 failed to deliver broad-based improvements in our nation’s standard of living for those who need it the most. And after historic records of inequality due to supply-side policies pursued since the 1970s, continuing the same approach to deliver the social and economic outcomes we value as a society would be misguided.

The new policies proposed in this essay would deliver positive returns on government investment. They would align the federal government and state and local governments with public institutions of higher learning and their students to not only break the stagnation of wages for low-income Americans but to also reap the other large potentials of the higher education system.

—Andria Smythe is an assistant professor of economics at Howard University.

Acknowledgments

End Notes

1. Philip A. Trostel, “The fiscal impacts of college attainment,” Research in Higher Education 51 (3) (2010): 220–247.

2. Ibid.

3. Raj Chetty and others, “Mobility report cards: The role of colleges in intergenerational mobility.” Technical report (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2017), available at http://www.equality-of-opportunity.org/papers/coll_mrc_paper.pdf.

4. Sara Goldrick-Rab and others, “Reducing income inequality in educational attainment: Experimental evidence on the impact of financial aid on college completion,” American Journal of Sociology 121 (6) (2016): 1762–1817.

5. Rachel E. Dwyer and Erik Olin Wright, “Low-Wage Job Growth, Polarization, and the Limits and Opportunities of the Service Economy,” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 5 (4) (2019): 56–76.

6. Austin Clemens and others, “Interactive: Comparing wages within and across demographic groups in the United States” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2019), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/demographic-group-wages-interactive/.

7. Jonathan Gruber and Simon Johnson, Jump-starting America: How breakthrough science can revive economic growth and the American dream (London: Hachette UK, 2019); Wesley M. Cohen, Richard R. Nelson, and John P. Walsh, “Links and impacts: the influence of public research on industrial R&D,” Management science 48 (1) (2002): 1–23; Naomi Hausman, “University innovation, local economic growth, and entrepreneurship.” Paper No. CES-WP-12-10 (U.S. Census Bureau Center for Economic Studies, 2012).

8. Matt Krupnick, “Colleges Pit Music Against Math as Funding Dries Up,” TIME Magazine, January 28 2015, available at https://time.com/3685071/college-majors-employment-graduation-rates/.

9. Daron Acemoglu, “Technical change, inequality, and the labor market,” Journal of Economic Literature 40 (1) (2002): 7–72.

10. Lisa Cook and Jan Gerson, “The implications of U.S. gender and racial disparities in income and wealth inequality at each stage of the innovation process” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2019), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/the-implications-of-u-s-gender-and-racial-disparities-in-income-and-wealth-inequality-at-each-stage-of-the-innovation-process/.

11. National Center for Education Statistics, “Table 314.20. Employees in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by sex, employment status, control and level of institution, and primary occupation: Selected years, fall 1991 through fall 2018” (n.d.), available at https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_314.20.asp.

12. Barb Rosewicz and Mike Maciag, “Nearly All States Suffer Declines in Education Jobs” (Washington: Pew Charitable Trust, 2020), available at https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2020/11/10/nearly-all-states-suffer-declines-in-education-jobs.

13. Douglas Woodward, Octavio Figueiredo, and Paulo Guimaraes, “Beyond the Silicon Valley: University R&D and high-technology location,” Journal of Urban Economics 60 (1) (2006): 15–32; Alexandra L. Cermeño, “Do universities generate spatial spillovers? Evidence from US counties between 1930 and 2010,” Journal of Economic Geography 19 (6) (2019): 1173–1210; Shimeng Liu, “Spillovers from universities: Evidence from the land-grant program,” Journal of Urban Economics 87 (2015): 25–41.

14. Robynn Cox, “Crime, Incarceration, and Employment in Light of the Great Recession,” Review of Black Political Economy 37(2010): 283–294, available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12114-010-9079-6.

15. National Center for Education Statistics, “Table 303.50. Total fall enrollment in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by level of enrollment, control and level of institution, attendance status, and age of student: 2017” (n.d.), available at https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_303.50.asp.

16. Steven C. Riggert and others, “Student employment and higher education: Empiricism and contradiction,” Review of Educational Research 76 (1) (2006): 63–92.

17. Martha Ross and Nicole Bateman, “Meet the Low-Wage Workforce” (Washington: Brookings Institution, 2019), available at https://www.brookings.edu/research/meet-the-low-wage-workforce/.

18. Enrico Moretti, “Estimating the social return to higher education: evidence from longitudinal and repeated cross-sectional data,” Journal of Econometrics 121 (1-2) (2004): 175–212.

19. Timothy J. Bartik, Brad Hershbein, and Marta Lachowska, “The merits of universal scholarships: Benefit-cost evidence from the Kalamazoo Promise,” Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis 7 (3) (2016): 400–433; Rodney J. Andrews, Stephen DesJardins, and Vimal Ranchhod, “The effects of the Kalamazoo Promise on college choice,” Economics of Education Review 29 (5) (2010): 722–737; Judith Scott-Clayton, “On money and motivation a quasi-experimental analysis of financial incentives for college achievement,” Journal of Human Resources 46 (3) (2011): 614–646; Goldrick-Rab and others, “Reducing income inequality in educational attainment: Experimental evidence on the impact of financial aid on college completion.”

20. Susan Dynarski and others, “Closing the gap: The effect of a targeted, tuition-free promise on college choices of high-achieving, low-income students.” Working Paper No. w25349 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2018).

21. David Callahan, “How the GI Bill Left Out African Americans,” Demos, November 11, 2013, available at https://www.demos.org/blog/how-gi-bill-left-out-african-americans.

22. Gruber and Johnson, Jump-starting America: How breakthrough science can revive economic growth and the American dream.

23. Joseph E. Stiglitz, Justin Yifu Lin, and Celestin Monga, The rejuvenation of industrial policy (Washington: The World Bank, 2013).

24. Stephen M. Gavazzi and E. Gordon Gee, Land-grant universities for the future: Higher education for the public good (Baltimore, MD: JHU Press, 2018).

25. Peter McPherson, Association of Public and Land-grant Universities, “Celebrating the 125th anniversary of the Morrill Act of 1890,” Press release, July 15 2015, available at https://www.aplu.org/news-and-media/blog/celebrating-the-125th-anniversary-of-the-morrill-act-of-1890.

26. U.S. Department of Education, “FACT SHEET: Spurring African-American STEM Degree Completion” ( 2016), available at https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/fact-sheet-spurring-african-american-stem-degree-completion.

27. McPherson, “Celebrating the 125th anniversary of the Morrill Act of 1890.”