Transforming U.S. supply chains to create good jobs

This essay is part of Boosting Wages for U.S. Workers in the New Economy, a compilation of 10 essays from leading economic thinkers who explore alternative policies for boosting wages and living standards, rooted in different structures that contribute to stagnant and unequal wages. The authors in the new book demonstrate that efforts to improve workers’ access to good jobs do not need to be limited to traditional labor policy. Policies relating to macroeconomics, to social services, and to market concentration also have direct relevance to wage levels and inequality, and can be useful tools for addressing them.

To read more about Boosting Wages for U.S. Workers in the New Economy 20 and download the full collection of essays, click here.

The two vignettes that open my essay illustrate the serious job-quality issues faced by U.S. workers and small businesses due to supply chain challenges. These challenges are due to the current structure of supply chains that reduce the bargaining power of workers and small businesses alike.

“After paying about $1,500 for home office equipment: a computer, two headsets, and a phone line dedicated to Arise; after paying Arise to run a check on her background; after passing Arise’s voice-assessment test and signing Arise’s nondisclosure form; after paying for and passing Arise’s introductory training, to which she devoted 3 days, unpaid; after paying for and passing a certification course to provide customer service for Arise client AT&T, to which she devoted 44 unpaid days; after then being informed she had to get more training yet—an additional 10 days, for which she was told she would be paid but wasn’t; and then, after finally getting a chance to sign up for hours and do work for which she would be paid (except for her time spent waiting for technical support, or researching customer issues, or huddling with supervisors), Tami Pendergraft spent 3 weeks fielding telephone calls from AT&T customers, after which she received a single paycheck. For $96.12.”1

The owner of a small rubber manufacturing plant in Cleveland explained to me (prior to the coronavirus recession) the consequences of his current low-wage policy. He paid his workers about $12 per hour, resulting in frequent absenteeism, the inability to fire inattentive workers because of lack of replacements, and late fees owed to his customers. Yet even with generous assumptions about the impact of higher wages on his workers’ efficiency, he makes a convincing case that raising wages by itself wouldn’t pay off. To fill his last 10 positions, he explained, he would need to raise wages for all 60 workers, including those who haven’t complained about pay so far. To fix his problems, he believed, he would need to invest in newer, more automated equipment, and pay enough (more than $20 per hour) to attract workers who could and would tend several machines. But such equipment costs millions of dollars, and if he takes out large loans to buy this equipment quickly, then it might lead to the loss of his house. He also would have to redesign many of his products to be compatible with the new equipment. He doubts that his customers would pay more, even if quality and delivery improve. And he’s locked in competition with other low-wage manufacturers, many of them abroad; his current operations are optimized for the purchasing environment he faces. He thinks he can probably survive until retirement by slowly shrinking as his equipment wears out.2

Overview

Decisions about how firms structure their supply chains matter greatly for working Americans, yet this topic rarely takes a front seat in discussions of policies to address income inequality. The customer service agent, the factory owner, and his workers in the vignettes above suffer significantly because of supply chain dysfunction.

Firms have restructured their supply chains significantly in recent decades. They have outsourced many activities previously done in-house by full-time employees to a complex web of outside firms. These outside suppliers manufacture components and provide services such as logistics, cleaning, and information technology.

Some of this restructuring contributes to innovation. As final products become more complex, it makes sense for large firms to purchase key components from firms that specialize in that technology or process.3 Supply networks based on product specialization do not necessarily reduce wages and could have the opposite effect.

But in other cases, firms outsource so as to offload production onto firms with weak bargaining power. These supplier firms have little ability to compete except by aggressively holding down wages. Aided by rampant worker misclassification, the erosion of workers’ bargaining power, and periods of weak regulatory enforcement, these forces further erode the quality of jobs for these downstream workers. This “fissured”4 or “low-road” model weakens innovation and suppresses wages, contributing to the erosion of U.S. workers’ standard of living.5

This essay explains how the structure of supply chains affects wages—in particular, why current models of outsourcing and offshoring manufacturing and services operations often lead to worse jobs. I propose policies to make supply chains fairer and argue that these better, “high-road” supply chains also serve other social goals, especially innovation. Specifically, I propose:

- Improving bargaining power for all workers

- Increasing the capability of small suppliers to innovate and provide good jobs

- Redesigning supply chains to promote collaboration among firms, using both carrots and sticks

- Creating a new federal institute to develop and diffuse management practices needed for high-road supply chains because the worker-power policies mentioned above may outlaw many techniques that firms have used to compete, such as low pay and union avoidance

- Enabling the federal government to promote high-road supply chains through its purchasing power

- Strengthening productive ecosystems

To the extent that workers are caught in supply chains with cutthroat competition, policies that attempt to upskill individual workers or contractors without changing the incentives of lead firms will not raise their wages. Thus, policies to reform supply chains will make other pro-worker policies more effective.

Supply chains defined

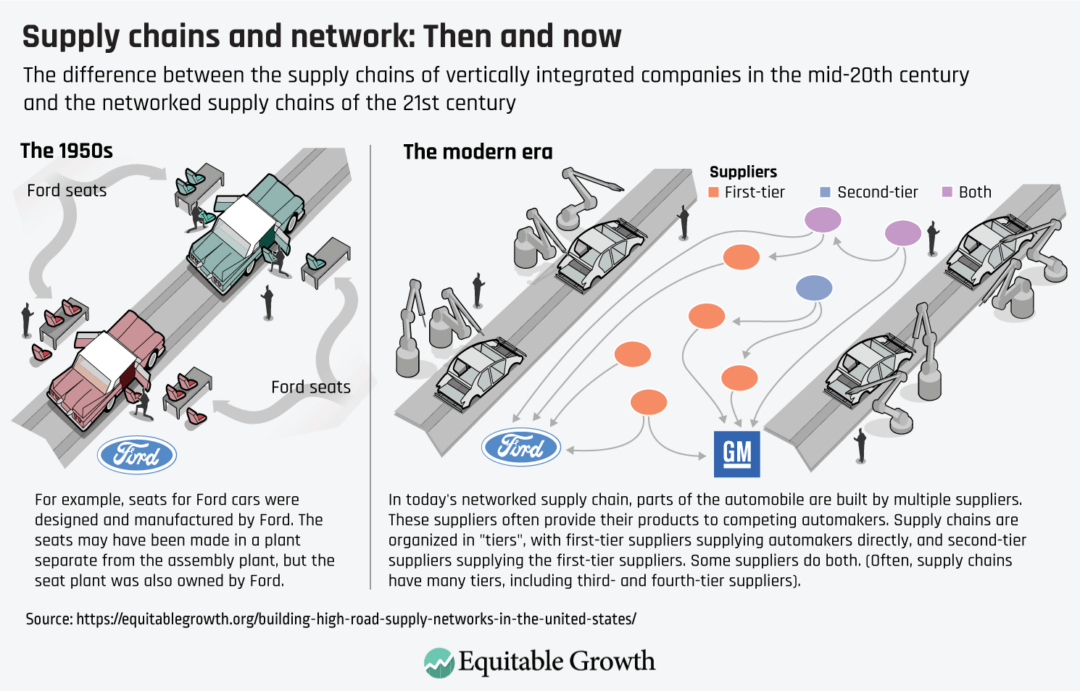

A supply chain is a network of firms involved in designing, producing inputs for, assembling, and distributing a good or service. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Overall, 43 percent of U.S. workers are in supply chain industries, employed either at lead firms or their suppliers.6 Domestic U.S. firms purchase intermediate inputs equal to about 50 percent of their overall output, while intermediate inputs comprise 75 percent of the output of U.S.-based multinationals. Because of deregulation, market failures, and corporate policies, the providers of these intermediate goods are often small, weak firms that compete by cutting corners on existing products and processes, and thus innovate less and pay less.7

The customer service agent in the opening vignette is considered an independent contractor. Even though lead firms (such as AT&T Inc. or Walt Disney Co.) demand investments and methods of work that are specific to them, these firms bear no legal responsibility under current (inadequate) law to provide her with work hours or to pay for benefits. In a previous decade, she might have been a direct employee of one of these firms, with stable hours and pay that reflected the handsome profits earned by the lead firm. The factory owner in the opening vignette would like to provide defect-free products to his customers and a living wage to his employees, but can’t find a way to fund the transformation required, given the terms of competition imposed by his customers and allowed by current law.

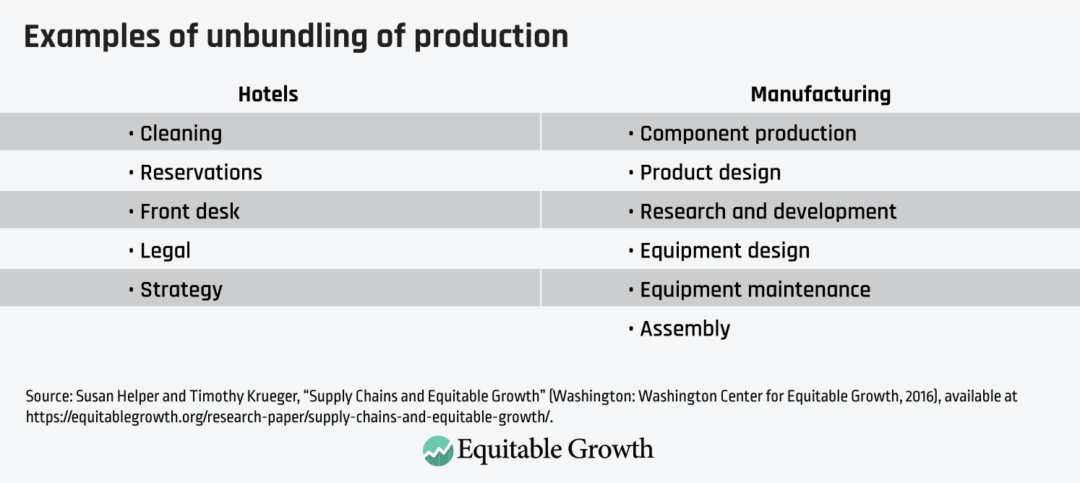

Low-road outsourcing is found in services such as payroll, janitorial work, and security, and now includes “employment activities that could be regarded as core to the company: housekeeping in hotels; cooking in restaurants; loading and unloading in retail distribution centers; even basic legal research in law firms.”8 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Some outsourcing contributes to innovation. As final products have become more complex, it makes sense for large firms to purchase key components from firms that specialize in that technology or process.9 Supply networks based on product specialization do not necessarily reduce wages and could have the opposite effect.

High-road supply chains are possible. Dana Corporation, for example, is a $9 billion supplier of propulsion systems for both conventional and electric vehicles. They have long supplied multiple automakers based on their innovative capabilities. The company provides a complete electric propulsion system, reducing barriers to entry into the electric vehicle market. Many Dana production workers are unionized, earning $16 to $25 per hour, plus benefits.10 These highly skilled workers were able to pivot quickly toward using 3-D printers to make face shields during the coronavirus pandemic.11

The impact of supply chains on U.S. employment

The outsourcing of work takes several forms, leading to a variety of types of workers in supply chains, sometimes working side by side. In many U.S. companies today, there are:

- Regular employees of lead firms

- Independent contractors working for other companies

- Independent contractors who are self-employed

- Subcontractors, including:

- At lead firm’s site

- At another site

These employees may be full time, part time, or temporary (except those in the first category).

These forms of outsourcing of employment, especially as carried out in the United States, typically create undesirable outcomes for most of these workers. Compared to regular employees in lead firms, workers in other forms of employment experience worse outcomes in areas such as wages, benefits, job security, and safety.12

Research by Nathan Wilmers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sloan School of Management, for example, finds that firms that sell to a small number of buyers pay lower wages than do similar firms with more customers; this greater dependence on large buyers lowers suppliers’ wages and accounts for 10 percent of wage stagnation in nonfinancial firms since the 1970s.13 It is important to note that most of the workers in Wilmers’ study are full-time, regular workers with all the rights and privileges that comes with that employment. Yet because they work in firms with less market power, they earn less.

Why are outsourced jobs generally worse for most workers?14 Research suggests several reasons:

Rent-sharing. Outsourced workers don’t benefit from norms of fairness that limit wage differentials within firms and encourage rent-sharing.15 It is also easier to fire a supplier than an internal division, due to social ties, complex flows of information, and funds. Thus, wages may creep up at an internal division, leading to cost increases that would lead to an outside firm losing business.

Design for supplier interchangeability. Many lead firms structure their supply chains to make contractors easily replaceable. For instance, U.S. automakers in the past brought product design and complex subassemblies in-house, making it possible to have contractors compete on simple tasks like making a small, pre-designed component. This strategy lowered barriers to entry to being a supplier, meaning that suppliers did not capture many rents.16 This has led to many lead firms in the apparel industry employing long chains of anonymous subcontractors; Walmart Corp., for example, professed to be surprised when goods marked with its label were found in the aftermath of the horrific Rana Plaza fire in Bangladesh.17

Monitoring without accountability. Other lead firms minutely specify the actions to be taken by workers in their supply chains, even those who are not their employees. That is, lead firms can control workers without taking responsibility for paying them benefits. Tight monitoring from lead firms means one of the few profit-making strategies available to subcontractors is to keep wages low.18 In much gig work, contractors have no pricing power; they must accept the price given to them in the app. In addition, workers for Uber Technologies Inc. and Lyft Inc. are tracked continuously by the two firms using GPS, rating workers based on their speed, harshness of braking, and the efficiency of their routes.19

Low supplier capability. As a result of lead firms’ strategies that maximize their replaceability and control their work methods, subcontractors’ ability to create or capture value is low. Innovation is often not feasible, since it typically requires collaboration and organizational slack. Even though investments might yield productivity improvements, contractors often don’t make them because they lack the capability to do so or would not capture much of the benefit due to fierce competition. As a result, subcontractors often cannot increase pay without risking bankruptcy.20

Weak ecosystems. Not only do U.S. suppliers lack support from lead firms, they are “home alone” in other ways as well.21 The reason: There are few institutions to help with innovation, training, or finance. 22 In contrast, Germany’s Mittelstand (medium-sized firms) are the backbone of the German manufacturing sector due to the help they get from community banks, applied research institutes, training institutions, and unions.23

Policy recommendations for fair, innovative supply chains

A different kind of outsourcing is possible: high-road supply networks that benefit firms, workers, and consumers alike.24 Under this model, there is greater collaboration between management and workers, and along the length of the supply chain, there is sharing of skills and ideas, new and innovative processes, and, ultimately, better products that can deliver higher profits to firms and higher wages to workers.25

Getting to this better outcome, however, requires overcoming both market and network failures. Understanding the rationale for existing practice is key to designing good policies. Below, I propose policies that aim to directly address each of the reasons that outsourcing increases wage inequality. The first two sets of policy recommendations support workers and firms, respectively, more or less in isolation. The last three sets of recommendations improve job quality by redesigning the structure of supply relationships in which workers and firms are embedded.

Reduce bargaining power differences between lead firms and outsourced workers by improving bargaining power for all workers

The pro-labor policies discussed throughout this book would make it easier for workers to choose unions, raise the minimum wage, and provide universal access to healthcare and retirement savings. These policies would promote high-road supply chains, while discouraging low-road strategies.26

Increase the capability of small firms for quality and innovation

One consequence of the low-road supply chain practices prevalent among many lead firms is that it hinders the development of innovative capabilities among their suppliers. Government can help upgrade these suppliers’ capabilities. For example, it can:

Provide technical assistance, subsidize, and directly engage in efforts to upgrade firms. In manufacturing, for exampe, the Manufacturing Extension Partnership, a state-federal program, has provided technical assistance to small firms since 1989. The program, at its current size, is very effective, with surveys suggesting that $1 of federal investment in the program leads to a $12 increase in economic activity. The Manufacturing Extension Partnership should be expanded significantly and given tools to work with supply chains as a whole, rather than firms one by one.

Develop and diffuse high-road management practices. Management practices within firms are a key determinant of productivity differentials. 27 The management of suppliers by lead firms affects their productivity and innovation.28 Much research documents the ways that firms can utilize high-road policies or good-jobs strategies to tap the knowledge of all their workers to create innovative products and processes.29

High-road firms remain in business while paying higher wages than their competitors because their highly skilled workers help these firms achieve high rates of innovation, quality, and fast response to unexpected situations. The resulting high productivity allows these firms to pay high wages while still making profits that are acceptable to the firms’ owners.

Diffusing new management practices is hard and risky, but these practices deliver social, as well as private, benefits.30 That’s why the government should fund the development and implementation of high-road management practice either through a consortium of universities or via a pilot project focused on manufacturing that could be established in the Manufacturing USA network.

Such an institute dedicated to managing a sustainable manufacturing ecosystem could collaborate with the Manufacturing Extension Partnership. The institute could develop and diffuse methods for managing high-road labor practices, establishing collaborative supplier relationships, and developing worker capabilities to participate in discussions of innovation. Such an institute or consortium would be particularly valuable in helping small firms adjust to the worker power policies mentioned above, which would make less effective (and possibly illegal) many of the low-road techniques that firms have used to compete, such as low pay and union avoidance.

Responding to these new rules would require not just changes in labor practices, but also changes in marketing, product development, and information technology to take advantage of the higher-skilled (but also higher-cost) labor entailed by the new policies.31

Redesign supply chains to promote collaboration and partnership among firms

Two problems with adopting solely the policies above is that firms embedded in low-road supply chains will have trouble finding capital to invest in innovation, and that these policies do little to promote information exchange among firms. Thus, it makes sense to redesign supply chains to allow for this greater investment and interchange.

Simply expanding the Manufacturing Extension Partnership alone is unlikely to lead to dramatic effects on job quality. The program already spends a great deal of time marketing its services, and its average project size is less than $15,000—not nearly enough to make the interlocking changes in product development, information technology, marketing, job design, and labor relations that are needed for a firm to move to the high road.

Making such a transition comes with significant risk. Firms need to invest in new equipment and training, and then live with expensive downtime as kinks are worked out of the new systems. The factory owner in the opening vignette could afford to hire the Manufacturing Extension Partnership to help with small projects, but can’t afford the high-road transformation described above. He’s locked in competition with other low-wage manufacturers (many of which are abroad), his current operations are optimized for the purchasing environment he faces, and he doesn’t think his customers would pay more for higher-quality products or reliable delivery.32

The federal government can promote supply-chain redesign in two main ways:

Encourage lead firms to build high-road supply chains. Low-road outsourcing strategies are costly to lead firms. These strategies slow innovation in auto manufacturing, for example.33 And they increase the frequency of infections in hospitals.34

In contrast, collaboration among firms along a supply chain can lead to greater productivity and innovation.35 By breaking down the usual silos within and between firms, lead firms can ensure that workers along the supply chain are exposed to ideas and training, to the ultimate benefit of all.

Collaborative relations could offset some of the stratification effects of outsourcing. Suppliers that collaborate with customers may be less interchangeable; workers at such suppliers may be more skilled and able to capture some of the supplier’s rents.36

One reason that firms don’t adopt high-road supply chain strategies is due to the slow diffusion of new management techniques. A new high-road supply chain initiative led by a new management institute or consortium should teach (and further develop) methods to help firms maximize the total value contribution of their suppliers rather than relying on price per-unit alone.37

That’s why the federal government should build on the work of the Obama administration in convening lead firms for a Supply Chain Innovation Initiative, which can drive innovative solutions while complementing a strong regulatory approach.38

Even with greater awareness, lead firms are unlikely to capture all the gains to high-road purchasing policies; the benefits of higher wages, for example, spill over to society as a whole.39 Thus, there remains a significant role for government in promoting high-road supply chains in its capacity both as a purchaser and as a regulator.

Act as a high-road purchaser. The federal government can buy preferentially from companies that use high-road practices. It can require its suppliers to pay prevailing wages, as is required in government-funded construction by the Davis-Bacon Act—a requirement that helps support the apprenticeships and training centers mentioned above. The Obama “Fair Pay and Safe Workplaces” executive order (which has since been overturned) blocked government purchases from companies if they or their suppliers had recent violations of labor laws.

Firms that receive government contracts should pay at least a living wage to their workers and subcontractors. In addition, government should allow prime contractors to count in their bids only 90 percent of the costs of small business subcontractors, as long as the forgiven costs went to investments in wages, training, or equipment. This would enable the government to invest more in contractors who invest more in their people.

The federal government also could offer technical assistance to its own and others’ suppliers by expanding the Manufacturing Extension Partnership and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Industrial Assessment Centers, which helps firms redesign their operation to conserve energy. Combining Buy America requirements with the Manufacturing Extension Partnership has proven effective. The Obama administration’s Department of Transportation enacted rules requiring that any time a federal contractor requested a waiver based on a claim that something can’t be made in America, it was published on a website for potential bidders and relevant stakeholders to see. The department contracted with the Manufacturing Extension Partnership’s supplier scouting service to identify firms that had the capability to fill these procurement needs.40

Government should use its purchasing power to incentivize lead firms to adopt high-road supply chains. Government purchasing policies should include carrots, such as the convening and funding of joint networking, roadmapping, and training efforts.41 But sticks are necessary, too, such as the enforcement of existing legal provisions that allow inspectors to confiscate “hot goods” at lead firms made by suppliers in violation of labor laws.42

The government should require firms that wish to exercise detailed control over workers to be accountable for those workers in order to end abuses such as those experienced by the customer service agent in the opening vignette. The new administration should put in place efforts to fight such misclassification of workers as independent contractors and to treat the lead firms that, in practice, direct the work as joint employers.

The new administration also should establish a commission to discover and end hidden incentives for firms to offshore their manufacturing and services operations. The new commission could recommend, for example, that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration should do unannounced inspections of offshore pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities as they already do for U.S.-based facilities.43

Finally, Congress should commission the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to study the collection of data on supply chains. A potential model is the U.S. Chambers of Commerce’s work with the U.S. Census Bureau to create a standard for learning and employment records that employers can use to keep track of employee information.44 Once this is done, firms can easily opt in to having certain fields within this information automatically uploaded to secure servers at statistical agencies.

Participation in such an effort could be made a condition of receiving government contracts or other government funds greater than a certain threshold, since such data would be needed to determine compliance with proposed requirements for government prime contractors and their subcontractors to provide “good jobs.”

Strengthen productive ecosystems

For reasons of both equity and efficiency, workers and small business should not depend solely on lead firms for strategic support. In the United States, the unionized construction sector has developed structures that create good jobs and fast diffusion of new techniques even though the industry remains characterized by small firms and work that is often intermittent.

Training is a way that workers can build their skills and thus potentially increase their wages. Building-trades unions work with signatory employers to provide apprenticeships, continuing-education programs, and portable benefits.45 Other unions have begun similar efforts to create career ladders for workers in the hotel and hospital sectors.46 A century ago, the federal government created an innovative farming sector by funding land grant universities, which led not only to the creation of knowledge but also to the creation of durable networks of researchers and practitioners through which such knowledge could quickly spread.47

Sectoral partnerships that include employers, unions, and community colleges have shown promise in providing stable, family-supporting jobs.48

Conclusion

This essay applies a supply-chain lens to the problem of income inequality. Some of the solutions proposed are fairly standard, such as various methods of paving the high road while blocking the low road. Others are more novel, including creating an institute to develop and diffuse management practices needed for high-road supply chains, directing the federal government to become a high-road purchaser and convenor of lead firms, and helping firms to collect better data on supply chains.

In closing, I note two key features of these proposals. First, complementary policies are needed to promote high-road supply chains. It is ineffective to simply attempt to enforce minimum wage laws when firms can go bankrupt and easily re-enter the market under a different name. Instead, long-term progress requires working with both suppliers and their buyers, using carrots (technical assistance) and sticks (“hot goods” enforcement) to transform production and purchasing practices toward a more productive model.49

Another example is that network failures make Buy America alone impractical.50 Over the past 20 years, the answer in U.S. manufacturing has often been to turn to China because firms are frequently unaware of suppliers nearby who could meet their needs. The combination of supplier scouting and Buy America discussed above is more powerful than either policy alone in bringing good jobs back.

Second, policies aimed at creating high-road supply chains will make other policies more effective at reducing inequality. Training, for example, may well not lead to increased wages if workers are employed by low-road suppliers. Suppliers may be unable to reorganize to productively use the new skills, and gains from improved performance may instead accrue to a monopsonistic lead firm.

If policies such as those suggested above are enacted, then lead firms are likely to reduce outsourcing for the purpose of maximizing their bargaining power, and move both to bring work back in-house and to engage with high-road suppliers for their unique capabilities.

— Susan Helper is the Carlton professor of economics at the Weatherhead School of Management at Case Western Reserve University, and a visiting scholar at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She was formerly chief economist at the U.S. Department of Commerce.

Acknowledgments

End Notes

1. Ken Armstrong, Justin Elliott, and Ariana Tobin, “Meet the Customer Service Reps for Disney and Airbnb Who Have to Pay to Talk to You.” Propublica, October 2, 2020, available at https://www.propublica.org/article/meet-the-customer-service-reps-for-disney-and-airbnb-who-have-to-pay-to-talk-to-you.

2. Susan Helper and Raphael Martins, “The High Road in Manufacturing.” In Barbara Dyer, ed., Creating Good Jobs: An Industry-based Strategy (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2020), available at https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/creating-good-jobs.

3. Bruce Kogut and Udo Zander, The Knowledge of the Firm in the Choice of the Mode of Technology Transfer (Philadelphia: Reginald H. Jones Center, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, 1991); AnnaLee Saxenian, Regional Advantage (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996).

4. David Weil, The Fissured Workplace (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), available at https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674975446.

5. Susan Helper and Timothy Krueger, “Supply Chains and Equitable Growth” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2016), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/research-paper/supply-chains-and-equitable-growth/. In many cases, firms have found workers with low bargaining power by offshoring (moving work outside the boundaries of the country). This restructuring is sometimes but not always accompanied by outsourcing (moving work outside the boundaries of the firm). For example, Ford buys seat covers from independent suppliers (offshoring and outsourcing together), and also owns an engine plant in Hermosillo, Mexico (offshoring without outsourcing). Ford also engages in offshoring for innovation; for example, designing its small-car engines in high-wage Germany.

6. Mercedes Delgado and Karen G. Mills, “The supply chain economy: A new industry categorization for understanding innovation in services,” Research Policy 49 (8) (2020).

7. Helper and Krueger, “Supply Chains and Equitable Growth.”

8. David Weil, “How to Make Employment Fair in an Age of Contracting and Temp Work,” Harvard Business Review, March 24, 2017, available at https://hbr.org/2017/03/making-employment-a-fair-deal-in-the-age-of-contracting-subcontracting-and-temp-work.

9. Kogut and Zander, The Knowledge of the Firm in the Choice of the Mode of Technology Transfer; Saxenian, Regional Advantage.

10. This is somewhat less than production workers at unionized automakers, but not less than at some nonunionized automakers.

11. “Dana: home page,” available at dana.com (last accessed December 20, 2020); John Hitch, “OEMs retool to produce PPE.” FleetOwner, April 8, 2020, available at https://www.fleetowner.com/covid-19-coverage/article/21128248/auto-oems-retool-to-produce-ppe; Larry P. Vellequette, “Tesla Roadster uses ‘cool’ Dana technology,” The Blade, November 14, 2009, available at https://www.toledoblade.com/local/2009/11/14/Tesla-Roadster-uses-cool-Dana-technology.html; United Steel Workers, “Summary of the Tentative Agreement between the United Steelworkers and Dana Holding Corporation” (2014), available at http://www.unionsrule.com/05-27-14_USW_Summary_of_Dana_Contract_-_FINAL.pdf.

12. Annette Bernhardt and others, “Domestic Outsourcing in the United States: A Research Agenda to Assess Trends and Effects on Job Quality.” Working Paper No. 16-253 (Upjohn Institute, 2016), available at https://irle.berkeley.edu/files/2016/Domestic-Outsourcing-in-the-US.pdf and http://cepr.net/images/stories/reports/working-paper-domestic-outsourcing-2016-03.pdf.

13. Nathan Wilmers, “Wage Stagnation and Buyer Power: How Buyer-Supplier Relations Affect U.S. Workers’ Wages, 1978 to 2014,” American Sociological Review 83 (2) (2018), available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0003122418762441.

14. Most research on the effects of outsourcing on job quality looks at low-wage workers and finds consistently negative effects. The few studies of outsourcing of high-wage work finds more mixed results. See Elizabeth Handwerker and James R. Spletzer, “The Role of Establishments and the Concentration of Occupations in Wage Inequality.” IZA DP No. 9294 (IZA Institute of Labor Economics, 2015), available at https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/9294/the-role-of-establishments-and-the-concentration-of-occupations-in-wage-inequality, for their finding that occupational concentration is correlated with growth in wage inequality between establishments, consistent with a story that people in outsourced high-wage occupations (such as consulting) would see their incomes rise, perhaps because they are freed from constraints of rent-sharing with people in lower-wage occupations in lead firms. On the other hand, unbundling of work and offshoring is affecting high-wage occupations (especially lawyers) as well; “business process outsourcing” often has led to reduced pay for many of the newly created subspecialities. See also Mari Sako, “Outsourcing and offshoring of professional services.” In Laura Empson, Daniel Muzio, Joseph P. Broschak, and Christopher Robin Hinings, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Professional Service Firms (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2015), pp. 327–347, available at https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/c886/450ee1d777371dd3b78cb830e0d2a516fd4f.pdf; William Henderson, “From Big Law to Lean Law,” International Review of Law and Economics 3 (2013), available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2356330.

15. Erica L.Groshen, “Sources of Intra-Industry Wage Dispersion: How Much Do Employers Matter?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 106 (3) (1991): 869–884, available at https://doi.org/10.2307/2937931.

16. Susan Helper and Rebecca Henderson, “Management Practices, Relational Contracts, and the Decline of General Motors,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 28 (1) (2014): 49–72, available at https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.28.1.49.

17. Gillian B. White, “What’s Changed Since More Than 1,110 People Died in Bangladesh’s Factory Collapse?” The Atlantic, May 3, 2017, available at https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/05/rana-plaza-four-years-later/525252/.

18. Weil, The Fissured Workplace.

19. National Employment Law Project, “Remote Control: The Truth and Proof About Gig Companies as Employers” (2020), available at https://s27147.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/NELP-PWF-Fact-Sheet-Remote-Control-Truth-Proof-Gig-Companies-Employers.pdf.

20. Weil, The Fissured Workplace; Helper and Martins, “The High Road in Manufacturing.”

21. Suzanne Berger, Making in America: From innovation to market (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), available at https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/making-america.

22. Stephen J. Ezell and Robert D. Atkinson, “International benchmarking of countries’ policies and programs supporting SME manufacturers” (Washington: The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, 2011), available at http://www.itif.org/files/2011-sme-manufacturing-tech-programss-new.pdf.

23. Susan Helper, Timothy Krueger, and Howard Wial, “Why Does Manufacturing Matter? Which Manufacturing Matters” (Washington: Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program, 2012), available at https://www.brookings.edu/research/why-does-manufacturing-matter-which-manufacturing-matters/. Like their U.S. counterparts, German janitors and security guards whose work is outsourced from lead firms see wage loss as well, at least in part because coverage of these institutions is not universal. See Deborah Goldschmidt and Johannes F. Schmieder, “The Rise of Domestic Outsourcing and the Evolution of the German Wage Structure,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 132 (3) (2017): 1165–1217, available at https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjx008.

24. Susan Helper, “Building high-road supply networks in the United States” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2019), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/building-high-road-supply-networks-in-the-united-states/.

25. Paul Osterman, ed., Creating Good Jobs: An Industry-Based Strategy (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2020), available at https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/creating-good-jobs; Helper and Martins, “The High Road in Manufacturing.”

26. Helper and Krueger, “Supply Chains and Equitable Growth.”

27. Nicholas Bloom and others, “Management in America.” Paper No. CES-WP-13-01 (U.S. Census Bureau Center for Economic Studies, 2013), available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2200954.

28. John V. Gray, Susan Helper, and Beverly Osborn, “Value first, cost later: Total value contribution as a new approach to sourcing decisions,” Journal of Operations Management 66 (6) (2020): 735–750, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/joom.1113; Helper and Martins, “The High Road in Manufacturing.”

29. Thomas A Kochan and others, “The Human Capital Dimensions of Sustainable Investment: What Investment Analysts Need to Know” (2013), available at https://cepr.net/images/stories/reports/applebaum-human-capital-dimensions-of-sustainable-investment-2013-02.pdf; Zeynep Ton, “Why ‘Good Jobs’ Are good for Retailers,” Harvard Business Review 90 (1-2) (2012): 124–31, available at https://hbr.org/2012/01/why-good-jobs-are-good-for-retailers.

30. Nicholas Bloom, Raffaella Sadun, and John Van Reenen, “Management as a Technology?” Working Paper No. w22327 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2016), available at https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w22327/w22327.pdf.

31. For examples from retail, see Ton, “Why ‘Good Jobs’ Are good for Retailers.” See below for a manufacturing example.

32. Helper and Martins, “The High Road in Manufacturing.”

33. Helper and Henderson, “Management Practices, Relational Contracts, and the Decline of General Motors.”

34. Adam Seth Litwin, Ariel C. Avgar, and Edmund R. Becker, “Superbugs vs. outsourced cleaners: Employment arrangements and the spread of healthcare-associated infections,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 70 (3) (2017): 610–641, available at https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793916654482.

35. John Paul MacDuffie and Susan Helper, “Collaboration in Supply Chains With and Without Trust.” In Charles Heckscher and Paul S. Alder, eds., The Firm as a Collaborative Community: The Reconstruction of Trust in the Knowledge Economy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), available at https://faculty.weatherhead.case.edu/susan-helper/papers/10-Heckscher-chap10%20(2).pdf.

36. Helper and Martins, “The High Road in Manufacturing.”

37. Gray, Helper, and Osborn, “Value first, cost later: Total value contribution as a new approach to sourcing decisions.”

38. The Executive Office of the President and the U.S. Department of Commerce, “Supply Chain Innovation: Strengthening America’s Small Manufacturers” (2015), available at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/supply_chain_innovation_report_final.pdf.

39. Helper and Krueger, “Supply Chains and Equitable Growth.”

40. National Institute of Standards and Technology, “Make it in America” (n.d.), available at https://www.nist.gov/system/files/documents/mep/MEP-MAKEINAMERICA-v3.pdf.

41. Helper, “Building high-road supply networks in the United States.”

42. David Weil, “Creating a strategic enforcement approach to address wage theft: One academic’s journey in organizational change,” Journal of Industrial Relations 60 (3) (2018): 437–460, available at https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185618765551.

43. Gray, Helper, and Osborn, “Value first, cost later: Total value contribution as a new approach to sourcing decisions.”

44. “Meet the T3 Network,” available at https://www.uschamberfoundation.org/t3-innovation/meet-network (last accessed December 21, 2020). A similar model could be explored for collecting data on supply chains. Many firms are struggling with how to collect and maintain these data for their own use; a national standard would eliminate duplication of effort for both customers and suppliers, and enhance public data collection. Participation in using such an effort could be made a condition of receiving government contracts or other government funds greater than a certain threshold, since such data would be needed to determine compliance with proposed requirements for government prime contractors and their subcontractors to provide “good jobs.”

45. Cihan Bilginsoy, “The Hazards of Training: Attrition and Retention in Construction Industry Apprenticeship Programs,” ILR Review 57 (1) (2003): 54–67, available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5119525_The_Hazards_of_Training_Attrition_and_Retention_in_Construction_Industry_Apprenticeship_Programs.

46. Eileen Appelbaum, Annette Bernhardt, and Richard J. Murnane, eds., Low-wage America: How Employers are Reshaping Opportunity in the Workplace (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2003), available at https://www.russellsage.org/publications/low-wage-america-1.

47. Irwin Feller and others, “The new agricultural research and technology transfer policy agenda,” Research Policy 16 (6) (1987): 315-325, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-7333(87)90017-5.

48. Joel S. Yudken, Thomas Croft, and Andrew Stettner, “Revitalizing America’s Manufacturing Communities” (New York: The Century Foundation, 2017), available at https://tcf.org/content/report/revitalizing-americas-manufacturing-communities.

49. Weil, “Creating a strategic enforcement approach to address wage theft: One academic’s journey in organizational change.”

50. Andrew Schrank and Josh Whitford, “Industrial Policy in the United States: A Neo-Polanyian Interpretation,” Politics & Society 37 (4) (2009): 521–53, available at https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329209351926.