Threats to social status and support for far-right political parties

Overview

Once on the political fringes, far-right parties have become established actors in many democracies. The European Parliament election in 2024, for example, resulted in far-right parties receiving more than 20 percent of the vote, and far-right parties are now represented in nearly all national parliaments in Europe. Outside of Europe, the far right has been in government in countries such as India, Israel, and Brazil. The current Trump administration in the United States also is dominated by far-right actors.

For a long time, one main research question on the political success of far-right parties was why is the far right successful in some countries but not in others? Some countries, such as Germany, were even considered immune to the contemporary far-right threat due to their particular national history.

It has now become clear that no country should be considered immune to the appeal of the far right. A mix of factors that is common to all post-industrial democracies has created a fertile ground for their political successes. Cases such as in Germany or Portugal show how quickly far-right parties can become established actors in national politics and receive a significant share of the vote.

It is thus not surprising that the rise of the far right has sparked considerable interest among researchers, commentators, and the broader public. Explanations for its success have often either focused on economic or cultural explanations. These explanations were often pitted against each other. But it is becoming increasingly clear that economic and cultural concerns are deeply intertwined among the supporters of far-right parties and across the broader electorate.

People do not necessarily separate these issues in their everyday lives—they see them as part of the same story about what is happening in the world around them. Rural resentment against urban elites has underpinnings of economic inequalities but, at the same time, is fueled by racial stereotypes and White identity politics.1 Competition in housing markets or underfunded schools can be regarded as the result of neoliberal economic policies, but they can be rhetorically connected to immigration, too.

A core idea for understanding how economic and cultural concerns are intertwined is as threats to social status.2 Social status as a concept dates back to the classic work of the early 20th century German sociologist Max Weber. It can be understood as peoples’ sense of value based on their position in society. While concepts such as class and socioeconomic status often refer to “objective” material values, such as levels of income and wealth, social status goes beyond material concerns and is based on a shared form of recognition across a society.3

Importantly, social status is not something that just exists in peoples’ heads: People experience tangible benefits or harms based on their social status. Social status determines how you are treated by others, how you can perform in certain contexts, and your access to different networks and social circles.

Typical sources of social status include education and occupation.4 Education and occupation do not only matter because they generate more or less income. They also come with different levels of prestige and power in society. Gender, race, and sexual identity similarly come with different levels of social status in society.

A growing body of research now suggests that when people see their social status threatened, they become more likely to support the far right. Importantly, the core group of supporters for the far right are not necessarily those who see themselves at the bottom of social hierarchies already but are those that perceive that they have something to lose.

Threats to social status can be both economic and cultural. They include developments that challenge a position in society that people value. These can be material economic risks that make it more likely that one’s standard of living will become significantly worse.5 But they also include transformations of roles in society.

Gender (being a man) and race (being White) were historically important sources of status in society. These roles as a source of status have been challenged in recent decades, and White men see their social status as threatened. Research by Princeton University’s Noam Gidron and Peter Hall at Harvard University, for example, demonstrates that compared to the early 1990s, the subjective social-status perceptions of men without a college degree have strongly declined in many countries in Europe and in the United States.6

In this essay, my focus is on economic sources of threats to status, focusing not on the effects of material hardships leading to more support for the far right, but rather on how economic changes and risks can contribute to a sense of potential loss of roles and routines that provide people with value, meaning, and identity. I focus on two economic threats to status: unemployment risk and rental market risks. Both a higher risk of unemployment and rising local rents contain a threat to (disposable) income and wealth. But these threats go beyond that, because people potentially will have to give up things that create a sense of value in their lives: their job, the areas in which they live, and the social circles in which they interact.

This essay summarizes my research on how economic threats to social status in the form of unemployment risk and rental market risk affects support for the far right in Europe.7 My work with collaborators shows that when people face a higher risk of unemployment, they become more likely to support far-right political parties. Within a household, one member at a high risk of unemployment is enough to increase support for the far right among both members of the household. Similarly, when people face increasing local rent prices—independent of the rent that they actually pay—they also become more likely to support the far right.

A focus on threats to social status helps answer one central question in the current ascent of the far right: Why do people who face adverse economic conditions vote for a party of the far right instead of a party of the left? Put differently: Why do people in these circumstances not support parties that would arguably provide better policy solutions for them? Why do they not support parties that promise labor market and rental market protections, better unemployment benefits, and rental controls?

There are many answers to these questions, and some are certainly related to social democratic and other center-left parties losing credibility on actually providing solutions to these issues.8 But beyond this, social status as a concept allows us to understand why far-right appeals resonate so well with people facing economic risks.

How threats to social status in labor markets affect support for the far right

A major source of threats to economic status is the risk of unemployment. Crucially, the focus here is on risk. In my research, I find that it is not economic hardship but the latent threat to livelihoods that matter for far-right support. My co-authors and I argue that when people are afraid of losing their jobs, their social status is threatened, and they become more likely to support the far right.

But we do not regard unemployment risk as a factor that only affects individuals. We also take into consideration that households are crucial sites for the formation of political preferences. When someone has a partner at a higher risk of unemployment, this affects their perceptions of threats to their social status—even if they themselves are relatively well-protected against unemployment.

We combine two data sources to test how unemployment risk affects support for the far right. We follow a common research approach, measuring unemployment risk as the share of people in an occupation (of the same age group and gender) who are unemployed. We can estimate this share based on a large-scale labor market survey, the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions, or EU SILC.9 Research indeed shows that there is a link between this objective measure of unemployment risk and subjective perceptions of risk.

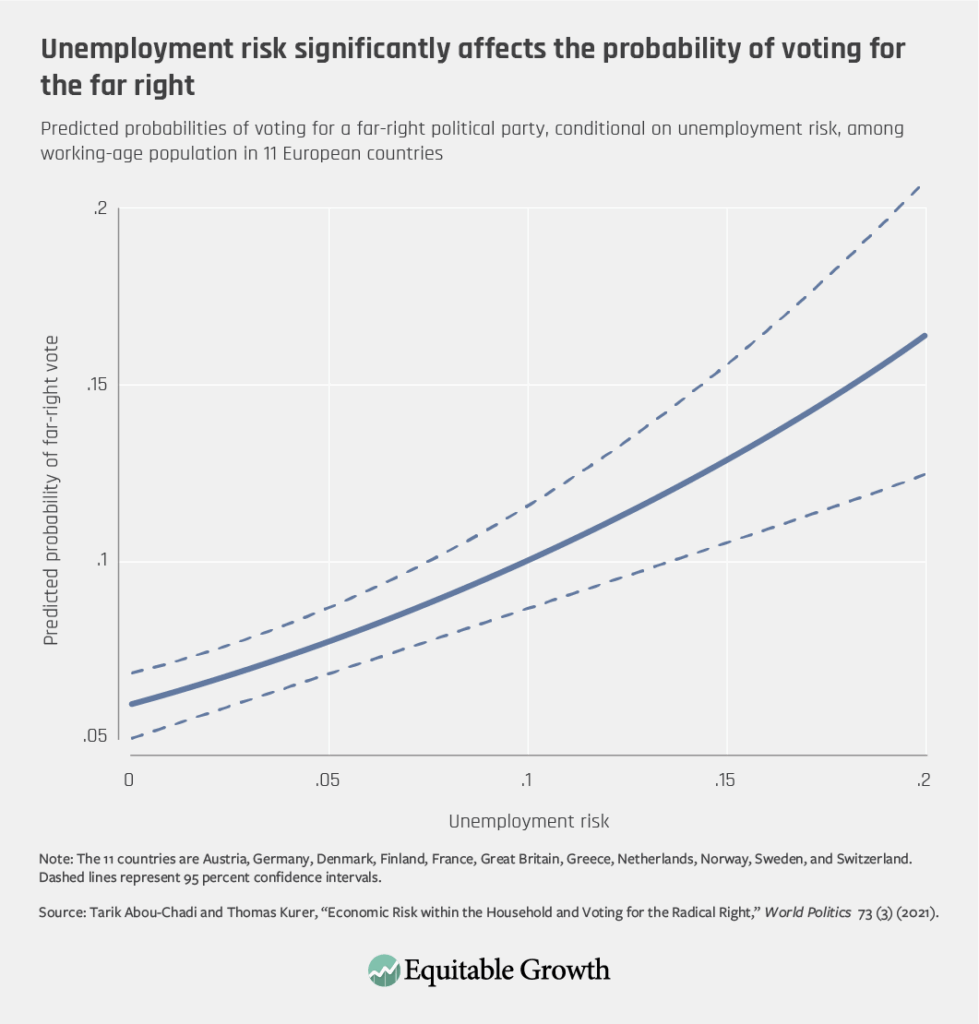

Based on a standard categorization of occupational groups, the International Labour Organization’s International Standard Classification of Occupations, we can combine the data on unemployment risk with survey data from the European Social Survey.10 These survey data include information on voting behavior, as well as on household composition and partner’s occupation. We analyze data for 11 European countries from 2002 until 2018,11 limiting our analysis to the working-age population between the ages of 18 and 65. We find that with increasing unemployment risk, people become significantly more likely to support a far-right party. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Holding a number of factors constant, when a person is at a higher risk of being unemployed, they show a higher propensity to vote for the radical right. Figure 1 shows that the predicted probability to vote for a radical right party increases from 0.06 to 0.15 with unemployment risk moving from low to high. Considering that the baseline probability to vote for the radical right is low in our sample—there are many countries that, before the 2010s, only saw very marginal radical right support—this is a substantive increase.

In our research, we are not only interested in how an individual’s unemployment risk affects their propensity to support the radical right but also how it interacts with a partner’s unemployment risk. We find that a partner’s risk also significantly affects someone’s likelihood to support the radical right. This is true for men and women. With the increasing risk of a partner being unemployed, people become more likely to support the far right. Even for people with relatively low unemployment risk themselves, if their partner has a high risk of unemployment, then they are more likely to support the far right.

In other words, one person at high unemployment risk in a household creates two radical-right voters.

How threats to social status in rental markets affect support for the far right

As a second threat to social status, we have investigated what we label rental market risk to social status linked to developments in local rental prices. Local rent increases constitute a significant risk to the economic and social foundations of people’s lives. When people see rents in their neighborhoods rising, they know that they potentially might not be able to continue to afford to live there in the future. This constitutes a threat to many aspects of a person’s life. Having to move can mean longer commutes to work, switching kids’ daycare or school, or being farther away from friends and family.

Consequently, local rent increases constitute a status threat independent of actual rent levels. Some rental markets, such as those in Germany, provide quite high protections for renters. Fixed-term contracts are rare, rent increases are regulated, and only under special circumstances (such as moving into a place themselves) can landlords terminate leases.

But even in these relatively protected circumstances, people are aware that changing life events (such as having kids) or landlord decisions to renovate a place or to move in themselves can quickly expose them to the new realities of a rental market. We thus expect rental market risk to increase support for the far right.

In our empirical analysis, we combine fine-grained data on rental price developments at the lowest ZIP code level with a long-running German household panel survey.12 If we just compare areas cross-sectionally, we find the patterns that we would expect. In high-rent inner-city areas, people are more likely to support left-progressive parties. This can largely be explained by highly educated professionals (a core electoral group of the progressive left) being more likely to move to areas with high rents. By contrast, far-right parties are strong in more rural areas and in eastern Germany, where rents are lower on average.

Our data, however, allow us to go beyond such comparisons. We can investigate how changing local rents affect people who already live in a neighborhood. We study people who have lived in the same neighborhood for at least 5 years and can thus analyze how changing local rents affect their party preferences. We focus on what researchers define as within-individual variation over time: We look at how the political preferences of the same person change when they are exposed to changing rent prices in their neighborhood.

We find that where local rents increase more, people with lower levels of income become significantly more likely to support the far-right Alternative für Deutschland. This is particularly pronounced in urban areas, where these changes can happen more rapidly and are easily observable through changing neighborhood compositions.

Importantly, we do not find that actual rent levels affect support for the AfD. Rather, it is rental market risk in the form of changes in local rent prices that matters for support of the far right.

Why these finding about the far right and social status matter

Our research shows that threats to social status in the form of unemployment risk and rental market risk significantly increase people’s propensity to support the far right. Crucially, we do not find actual economic hardship—unemployment status and rent levels—to matter in these contexts, but rather the latent risk of losing social status. This is in line with other work on the risk of losing jobs to automation.13 People become more likely to support the far right when they see their living conditions threatened, not necessarily when they have already experienced loss and hardship.

This means that the common narrative of populist far-right supporters as the “left behind” might create a wrong image of who these voters are. Far-right supporters are better understood as the people in the lower middle classes and the so-called petite bourgeoisie—the owners or managers of small businesses who are not struggling to provide the bare minimum for themselves but rather have accumulated material and cultural sources of status that they now see threatened.

Importantly, these people do not support the far right because of the its policy proposals. People who are at higher risk of unemployment do not support the far right because they think that the far right has the best labor market policies, nor do people facing increasing local rents embrace the far right for their housing policies. Far-right support in response to threats to the current social status of people should thus not be understood as an instrumental wish for better policies provided by these actors.

Instead, people seek out the far right to reinstate a social order that guarantees their privileged place in it. It constitutes a nostalgia for a time that maybe never existed. Far-right parties receive support among these voters not for their promises to change policy but for their promises to change politics and polity.

Left-wing and progressive parties do not currently provide any such appeals at scale. They have become parties of policy.14 They see and portray themselves as solving problems and providing incremental changes to small-scale questions. They value pragmatism over ideology. The answer to the question of why economic risk does not translate into support for the left lies—at least partially—in this discrepancy between demand and supply.

Conclusion

What can we learn from the relationship between threats to social status and far-right support for current developments in European and U.S. politics? In particular, what are the lessons for those who are interested in crafting economically and socially progressive policy agendas and who want to defend liberal democracy against the threat from the far right?

First, our findings show that the economy certainly matters for understanding support for the far right. But those findings also should caution against a reductionist and materialist understanding of far-right support. Economic hardship is not a necessary condition for someone to support the far right: Far-right support does not disappear in economically good times.

Indeed, racism, sexism, antisemitism, and anti-LGBTQ+ attitudes remain at the core of far-right support.15 We can find these sentiments across all class groups and across all levels of education. The far right as a political, cultural, and social project has successfully linked perceptions of threats to economic well-being with hostility toward minority groups. But this does not mean that if progressive policymakers reduce economic uncertainty, people will necessarily reduce their hostility toward these groups. Racism, sexism, and transphobia have become essential building blocks of some voters’ political identities and have become normalized as elements of political discourse.

Economic and social policies will not be enough to reverse these dynamics. Yet economic policies do matter. The erosion of a social safety net, the decline in public services, and the deterioration of government-provided health care that have resulted from austerity policies have significantly contributed to creating grievances that the far right can exploit.16 Continuing these policies means creating a steady or growing reservoir of far-right voters. Shifting away from these policies is a necessary part of a strategy to reduce far-right support.

At the same time, it should be clear that this is a long-term, not a short-term, strategy and that it is a necessary but not a sufficient condition to contain the far right. As Columbia University’s Alexander Hertel-Fernandez and Shayna Strom, the president and CEO of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, have argued in this series, “thin deliverism” will not work.17 The sources of far-right support are too structural. Too many politicians still believe that solving problems will immediately reduce the appeal of the far right. This won’t happen.

The far right is here to stay for the foreseeable future. Politicians and activists need to embrace the long-term challenge. In the short term, questions of politics and polity will be more important to protect liberal democracy from the far right. But economic and social policies will play an important role in shaping the conditions for far-right party support in the long run.

About the author

Tarik Abou-Chadi is a professor in European Union and comparative European politics at the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Oxford’s Nuffield College.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!

End Notes

1. Katherine Cramer, The politics of resentment: Rural consciousness in Wisconsin and the rise of Scott Walker (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

2. Noam Gidron and Peter A. Hall, “The politics of social status: Economic and cultural roots of the populist right,” The British journal of sociology 68 (Suppl 1) (2017): S57–S84, available at https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/hall/files/gidronhallbjs2017.pdf; Noam Gidron and Peter A. Hall, “Populism as a Problem of Social Integration,” Comparative Political Studies 53 (7) (2020): 1027–59, available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0010414019879947.

3. Cecilia L. Ridgeway, Status: Why is it everywhere? Why does it matter? (New York: The Russell Sage Foundation, 2019).

4. Magdalena Breyer, “Perceptions of the social status hierarchy and its cultural and economic sources,” European Journal of Political Research 64 (2) (2025): 810–33, available at https://ejpr.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1475-6765.12712.

5. Thomas Kurer, “The Declining Middle: Occupational Change, Social Status, and the Populist Right,” Comparative Political Studies 53 (10-11) (2020): 1798–1835, available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0010414020912283.

6. Gidron and Hall, “The politics of social status: Economic and cultural roots of the populist right.”

7. Tarik Abou-Chadi and Thomas Kurer, “Economic Risk within the Household and Voting for the Radical Right,” World Politics 73 (3) (2021): 482–511, available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352259208_Economic_Risk_within_the_Household_and_Voting_for_the_Radical_Right; Tarik Abou-Chadi, Denis Cohen, and Thomas Kurer, “Rental Market Risk and Radical Right Support,” Comparative Political Studies 0 (0) (2024), available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00104140241306963.

8. Geoffrey Evans and James Tilley, The new politics of class: The political exclusion of the British working class (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017); Stephanie L. Mudge, Leftism Reinvented: Western Parties from Socialism to Neoliberalism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018).

9. Eurostat, ”EU statistics on income and living conditions,” available at https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-statistics-on-income-and-living-conditions (last accessed August 2025).

10. “European Social Survey,” available at https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/ (last accessed August 2025).

11. The 11 countries are Austria, Germany, Denmark, Finland, France, Great Britain, Greece, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland.

12. “The Social-Economic Panel (SOEP),” available at https://www.diw.de/de/diw_01.c.412809.de/sozio-oekonomisches_panel__soep.html (last accessed August 2025).

13. Thomas Kurer, “The Declining Middle: Occupational Change, Social Status, and the Populist Right,” Comparative Political Studies 53 (10-11) (2020): 1798–1835, available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0010414020912283.

14. Mudge, Leftism Reinvented: Western Parties from Socialism to Neoliberalism.

15. Cas Mudde, The far right today (Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2019); Gefjon Off, “Gender equality salience, backlash and radical right voting in the gender-equal context of Sweden,” West European Politics 46 (3) (2023): 451–76, available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361578301_Gender_equality_salience_backlash_and_radical_right_voting_in_the_gender-equal_context_of_Sweden; Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart, Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

16. Simone Cremaschi and others, “Geographies of discontent: Public service deprivation and the rise of the far right in Italy,” American Journal of Political Science (2024),available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ajps.12936; Simone Cremaschi, Nicola Bariletto, and Catherine E. de Vries, “Without Roots: The Political Consequences of Collective Economic Shocks,” American Political Science Review (2025): 1–20, available at https://www.scienceopen.com/document?vid=5abd9ffd-af45-4423-91af-ad7da2f74e75; Thiemo Fetzer, “Did Austerity Cause Brexit?,” American Economic Review 109 (11) (2019): 3849–86, available at https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20181164.

17. Alexander Hertel-Fernandez and Shayna Strom, “Designing economic policy that strengthens U.S. democracy and incorporates people’s lived experiences” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2025), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/designing-economic-policy-that-strengthens-u-s-democracy-and-incorporates-peoples-lived-experiences/.

Stay updated on our latest research