The unequal impact of the Federal Reserve’s monetary tightening and easing on firms in the United States

The easing of inflation in the U.S. economy beginning in 2022 and recent signs of weakness in the U.S. labor market over the past several quarters have led households and financial market participants alike to form expectations that the Federal Reserve might embark on an easing cycle over the rest of 2024. This potential shift would mark the first reversal after a rapid series of interest rate increases by the Fed in 2022 and 2023.

But the Fed’s expected decision to cut its benchmark federal funds rate later this month raises an important question: Do interest rate hikes affect the U.S. economy to the same extent as rate cuts? Existing economic research on the transmission of monetary policy decisions into the broader economy documents that monetary tightening tends to have stronger effects than easing, using aggregate historical data.

Yet few studies have explored these asymmetric effects at the micro-level, particularly how individual firms respond differently to monetary tightening and easing. In my recent working paper, I explore these asymmetries using firm-level data to provide a deeper understanding of how various types of firms respond differently to monetary tightening and easing. I find that tightening is more effective than easing at the firm level for monetary policymaking but also that heterogeneity among firms also impacts the effectiveness of monetary policymaking when the Fed tightens or eases the federal funds rate.

To explore the asymmetry in firms’ responses to monetary policy, I combine identified periods of monetary easing and tightening with quarterly Compustat firm-level data, spanning from the third quarter of 1980 to the fourth quarter of 2019. I chose this period of time because it was before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequently sharp, but short, recession in 2020.

This comprehensive dataset further allows me to explore a wide group of financial constraint proxies, such as firm size, dividend status, credit ratings, and age, and to examine whether firms with certain financial characteristics exhibit distinct responses to monetary policy shocks in the form of interest rate cuts or hikes.

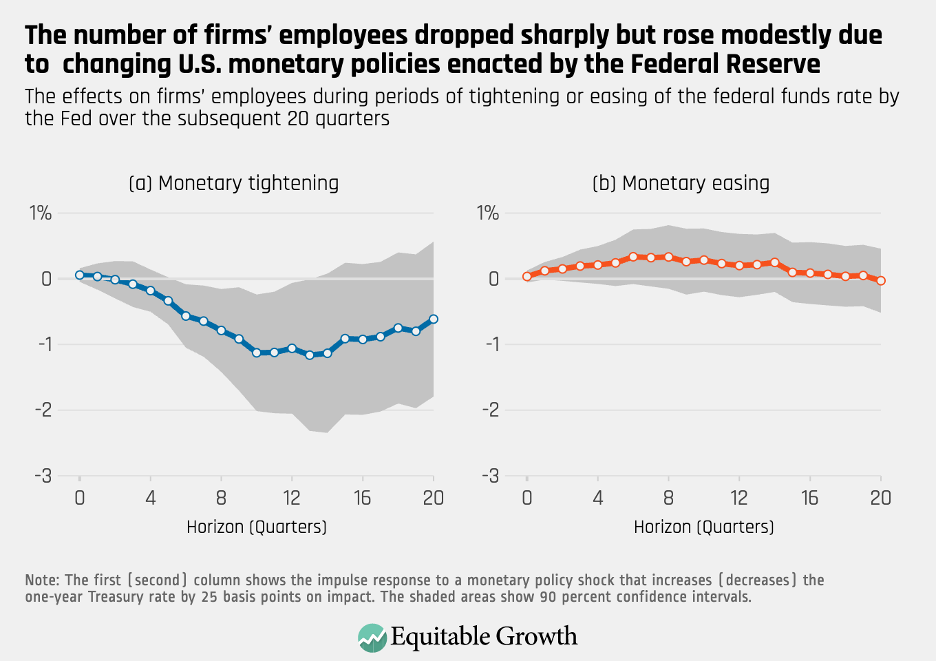

My analysis first focuses on how periods of monetary tightening and easing differentially impact firm-level employment, sales, and investment rates. For employment, the results indicate that a 25 basis-point monetary tightening of the federal funds rate leads to an approximately 1.1 percent drop in employment 10 quarters after the policy change. In contrast, an equal-sized easing of the federal funds rate only leads to a maximum 0.3 percent increase in employment over the same period, and the effect is insignificant across the horizon. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

These findings suggest that monetary tightening easily transmits into more job destruction, yet monetary expansions produce less job creation. This difference may be attributable to factors such as firms’ hiring costs and a slower job-finding rate among workers caused by existing job-matching frictions across U.S. labor markets.

This result is also consistent with evidence of a downward nominal wage rigidity channel. Downward nominal wage rigidity occurs when wages fail to decrease during economic downturns due to worker resistance to wage cuts. As a result, firms may reduce hiring or cut jobs instead, leading to greater employment losses. For instance, I and my colleague at Bentley University, Laura E. Jackson, show that the employment impact of monetary tightening may be exacerbated in certain sectors with larger downward wage rigidity.

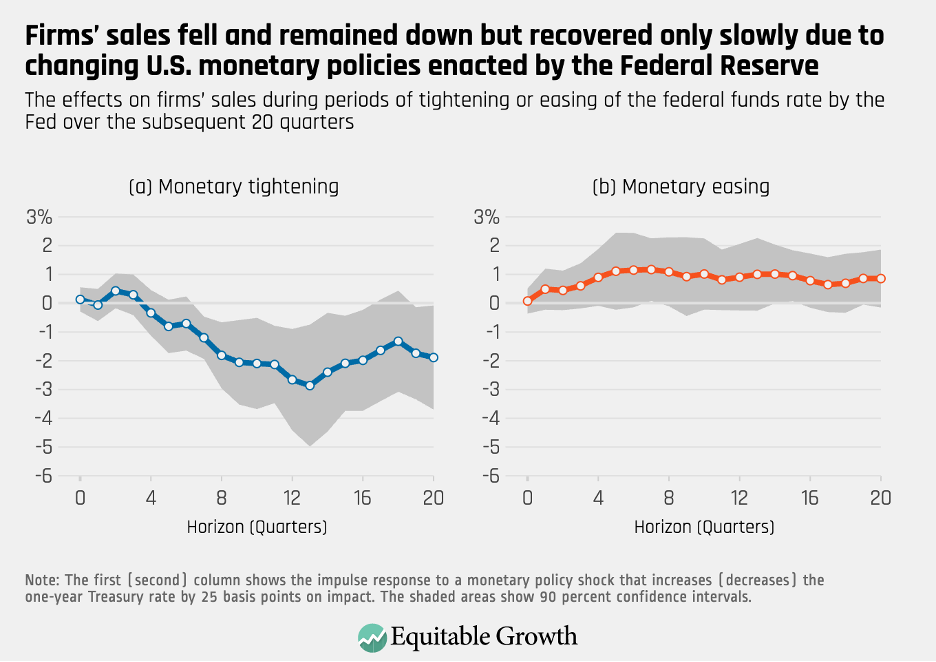

Consistent with these employment findings, I show in my recent working paper that firms’ sales show a peak decline of 2.9 percent over 13 quarters following monetary policy tightening. This effect is significant from quarter 4 to quarter 16, with sales beginning to recover only about 3 years after the shock. In contrast, a monetary expansion leads to a maximum increase in sales of about 1 percent a year after policy shifts, but this effect is less significant, consistent with the employment response to monetary easing. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Overall, sales exhibit a stronger, and persistent, response to monetary tightening than easing, aligning with the observed impact on employment levels, as shown in Figure 1.

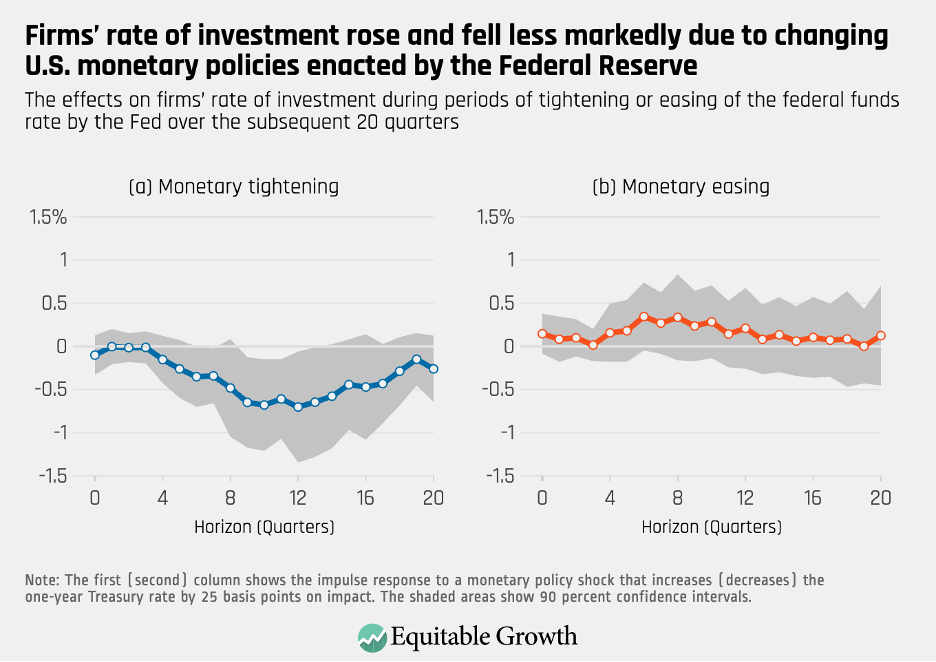

The investment response to monetary tightening or easing, however, exhibits less pronounced asymmetry, compared to the employment and sales results. In particular, a 25 basis-point monetary tightening results in a peak reduction of 0.7 percentage points in firms’ rate of investment, occurring 11 quarters after the shock. In contrast, monetary expansions have much weaker effects on investment. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

The asymmetry tests reveal that investment responses show a lower degree of asymmetry than the employment and sales responses. This lower degree of asymmetry might be explained by the firm specificity of capital and the irreversibility of investment decisions once they are made. Since capital has firm-level specificity, many firms may find limited benefits in selling their capital during periods of monetary tightening. In contrast, labor is relatively less firm-specific, making it easier for firms to adjust their employment levels following a monetary tightening.

In my working paper, I also trace alternative proxies for financial frictions and find considerable heterogeneity in firms’ responses to monetary policy shocks by the Fed. My results find significant heterogeneity depending on the size of firms, dividend statuses, their credit ratings, and age, corroborating earlier research on financial constraints.

Specifically, employment levels decline more sharply in response to monetary tightening, particularly among small firms, non-dividend-paying firms, those firms with low credit ratings, and younger firms. Similarly, I find that sales and investments by firms with low credit ratings respond significantly more to monetary tightening, compared to those with high credit ratings.

This suggests that firms with more severe financial constraints respond more to monetary tightening, which is consistent with the financial accelerator framework suggesting that firms with weaker balance sheets experience higher borrowing costs, thereby amplifying the negative effects of tighter monetary policy on economic activity.

My findings suggest that monetary tightening is more impactful than when the Fed eases its federal funds rate, particularly on firm-level employment and sales. These findings also show that the impact of monetary policy tightening and easing varies significantly across different types of firms. Overall, this paper highlights that monetary policy decision-making does not affect all firms equally, providing monetary policymakers with a practical rule of thumb for understanding the scope of their policymaking after accounting for the asymmetric effects on different types of U.S. firms.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!