The status of U.S. labor market data amid the government shutdown

Overview

The federal government ground to a halt earlier this week as Congress was unable to reach a bipartisan agreement on continuing funding after annual appropriations ran out at the end of the 2025 fiscal year on September 30. The consequences of such a shutdown—the nation’s first in 6 years—could fall disproportionately on federal workers, as furloughed federal employees lose income and the White House threatens permanent layoffs.

Also under threat are the federal data used to track the health and trajectory of the U.S. economy. As the U.S. Labor Department made clear before the shutdown began, regular collection and publication of labor market data would halt if the federal government is not funded.

In the short run, this means that the researchers, investors, business leaders, and consumers who rely on the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ monthly employment situation report, due to have been released this morning, are operating in the dark. In the longer run, critical data collection operations—including for the decennial census that will be released in 2030—could be set back at a time when BLS funding is already at a multi-decade low. As Equitable Growth grantee Peter Norlander wrote in a recent piece on data democratization, individuals and organizations can take steps to protect and preserve U.S. labor market data, but there is no substitute for the robust, independent data produced by the U.S. government.

This column first describes the work of the Bureau of Labor Statistics. It then turns to how BLS data are used by individuals, businesses, and policymakers alike, before detailing the impact of the agency not releasing its employment situation report this month due to the shutdown. It closes by explaining recent BLS budget constraints and how this affects the agency’s operations and data collection.

What is the Bureau of Labor Statistics?

The Bureau of Labor Statistics is a premier statistical organization of the U.S. federal government and part of an ecosystem that includes several other federal agencies devoted to data collection and analysis. The U.S. federal statistical system is responsible for producing public reports and metrics that help policymakers, firms, and individuals make informed decisions about the U.S. economy. Accuracy and data confidentiality are key to the success of the U.S. federal statistical system.

The agency organizes several regular data releases, including the monthly employment situation report, which includes insights from two key programs: the Current Population Survey, also known as the household survey, and the Current Employment Statistics, also known as the establishment survey. It also produces a range of other important metrics, including job openings and turnover rates, consumer and producer measures of inflation, and employment by industry and geographic region.

How BLS data are used

Businesses, policymakers, researchers, and everyday Americans use BLS data directly and indirectly to make informed economic decisions. Individuals look to headline inflation data to make decisions about durable goods purchases, while businesses use employment and inflation data to weigh investment decisions. A BLS factsheet notes that key corporate functions—including compensation and benefits analysis and contract administration—are often guided by detailed industry-level BLS data releases on wage and price trends.

In a paper for the National Association for Business Economics, former BLS Commissioner Erica Groshen listed dozens of uses of BLS data by private citizens, businesses, researchers, advocacy groups, and governments. Groshen wrote that BLS data guides individual decisions about where to live, how to invest, and what career to pursue, as well as business decisions about setting wages and prices, managing employee turnover, improving workplace safety, estimating financial risk, and validating private data sources.

The precise economic value of federal statistical data is difficult to calculate, but the myriad uses of the data suggest disruptions to BLS work could slow decision-making and lead to riskier choices across the U.S. economy.

The impact of not releasing an October employment situation report

One of the very first casualties of this government shutdown is more information about how everyday workers are doing across the U.S. economy. The labor market has recently been a source of real strength in the U.S. economy, but it has been slowing down considerably over the past few months. The latest BLS employment situation report, which would have included new data from September along with adjustments to data from prior months, could have indicated whether that labor market slowdown is continuing, accelerating, or reversing.

The economy is very much on a “knife’s edge,” and every data point matters for policymakers who should be trying to strengthen the economy. Second quarter Gross Domestic Product growth was strong, but some of that strength was likely a bounce back from incredibly weak first quarter GDP growth. What we know for sure is that the economy has been creating fewer jobs, wage growth has been slowing, and middle-class consumers have been feeling pinched.

This slowdown in the U.S. labor market is likely to be made worse by the Trump administration’s calls to cut public services, specifically health care assistance. These cuts would hurt the economy by putting more strain on already-overburdened middle-class budgets.

More broadly, the disruptions that will result from this government shutdown will put further pressure on the cracks in our already-brittle economy. It is hard to predict the exact ways in which a shutdown will cause economic disruptions and pain, but that uncertainty is part of the problem and creates big risks for the economy.

BLS funding has fallen dramatically in recent years

Regular public data releases, such as the BLS monthly employment situation report, could help mitigate some of this uncertainty. Yet the shutdown is not solely to blame for strains placed on BLS data collection. The agency’s declining budget also plays a role.

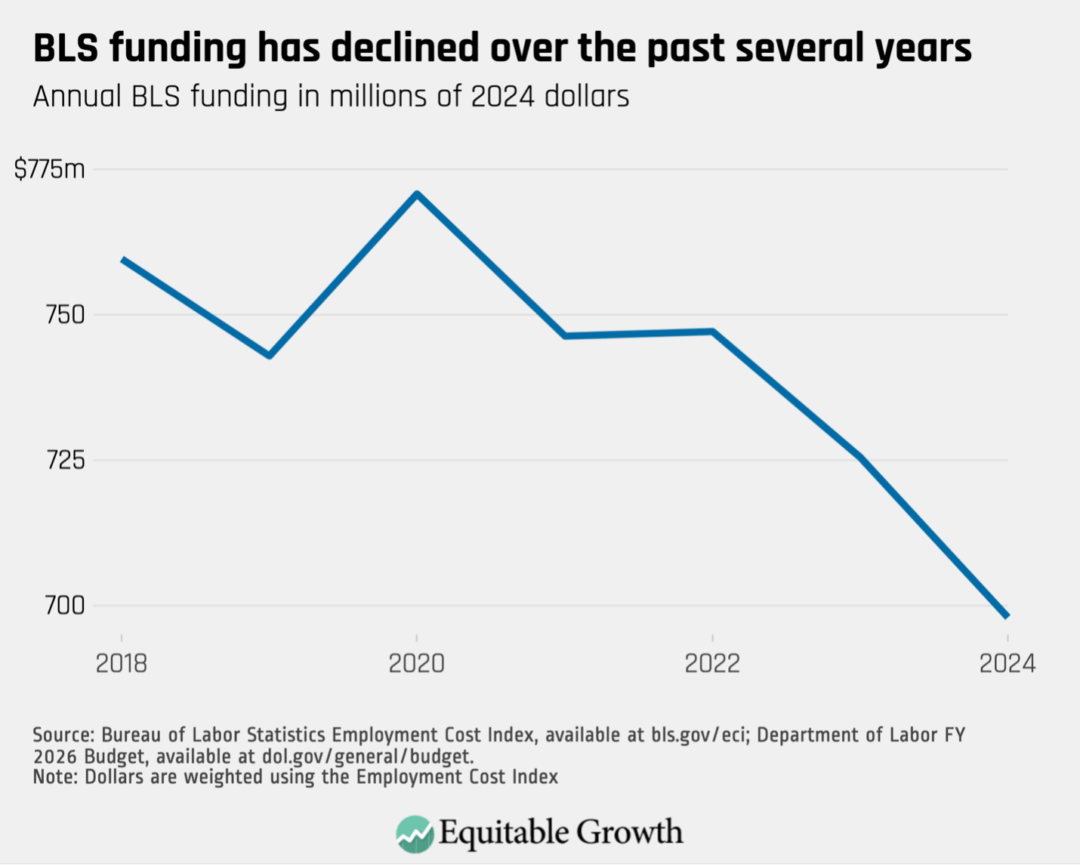

Economists and policymakers alike have warned for years that declining real funding for the Bureau of Labor Statistics has stymied the agency’s efforts to improve and innovate its data collection and analysis. In October 2018, for example, the Council of Professional Associations on Federal Statistics wrote in a blog post that the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ purchasing power has dropped $120 million, as flat nominal funding is eroded by inflation. Equitable Growth analysis of federal budget and inflation data show another at least $50 million in eroded funding since 2018. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

In May 2024, the co-chairs of the professional association Friends of BLS—both former BLS commissioners—wrote in a letter to congressional appropriators that BLS funding must be increased to improve Current Population Survey data collection, including through an internet self-response method. Similarly, experts at the Center for American Progress wrote in September 2024 that the survey needs additional funding to expand its sample size, which has remained at roughly 70,000 U.S. households since 2001.

In a “Commissioner’s Corner” blog post in December 2024, then-BLS Commissioner Erika McEntarfer wrote about the need for improved BLS funding, particularly for the agency’s IT systems, to address survey nonresponse issues exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. In May 2025, the Friends of BLS co-chairs once again wrote to lawmakers warning of the 22 percent real decline in agency funding since 2010 and highlighting funding needs, including modernization of the Current Population Survey.

Conclusion

The government shutdown’s impact extends far beyond federal data collection and release. But the lack of an employment situation report today will only exacerbate the uncertainty facing the U.S. economy of late. As budget negotiations work through Congress for fiscal year 2026, policymakers should consider increasing the BLS budget to ensure continuity, accuracy, and reliability of these vital economic statistics.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!

Stay updated on our latest research