The role of private equity in the U.S. economy, and whether and how favorable tax policies for the sector need to be reformed

Overview

The increasing impact of private equity firms upon large swaths of the U.S. economy in recent decades is drawing more attention to the tax treatment of these firms as they engage in their business of buying, operating, and selling companies. Today, private equity deals account for more than one-third of all merger and acquisition activity in the United States, with total annual deal value in 2021 and 2022 of more than $1 trillion, comprising about 9,000 deals each year.1 These deals benefit from certain tax policies.

Since the 1990s, there have been efforts to remove one key advantage, which is the taxation of private equity profits at a relatively low capital gains rate. Private equity firms have effectively opposed such measures by arguing that the low rate enables them to finance smaller enterprises, which are crucial for the economy, while generating necessary returns for institutional investors such as pension funds.

In this issue brief, we shed light on this debate by laying out the facts about U.S. tax policy and private equity. We begin by providing an overview of the private equity business model and the incentive structure it creates. Broadly, we show how these firms raise funds from institutional investors and high-net-worth individuals, then invest those funds in companies across the U.S. economic landscape, manage them to increase cash flow while they own them, and then sell those companies, usually when individual private equity funds near their usual 10-year lifespan.

We then describe the tax benefits that are relevant to the private equity industry. The most important are:

- The taxation of carried interest at the capital gains rate. This means that the primary compensation of general partners (who manage private equity funds) is taxed at 20 percent rather than at higher personal income tax rates.

- The tax deductibility of interest paid on debt. This creates tax shields that boost returns.

Private equity firms also benefit from fee waivers, qualified business income deductions, depreciation allowances, real estate benefits, and exemption from the new corporate minimum tax.

In a more speculative discussion, we then explore the possible impacts of these advantages on the investment community, on the companies that private equity firms acquire, and on society more broadly. Ultimately, we present policy recommendations and assess the potential costs and benefits associated with tax reform.

Specifically, although there is a need for more research, we believe it is unlikely that taxing the income of private equity managers at the same level as other professional services—rather than at the capital gains rate—would have major deleterious impacts on the private equity industry or its benefits to the U.S. economy. Policymakers should balance the interests of investors in private equity with the broader public interest and consider the potential positive impacts of tax reform.

We believe it is unlikely that taxing the income of private equity managers at the same level as other professional services—rather than at the capital gains rate—would have major deleterious impacts on the private equity industry or its benefits to the U.S. economy.

The tax advantages wielded by private equity firms bear increased scrutiny because of their implications for business and society. These firms typically generate high returns and contribute to economic growth, but tax benefits can lead to reduced public revenue, widening income inequality, and short-term investment strategies. Thoughtful tax reform could promote equitable access to economic opportunities and enhance positive contributions to the economy and society.

The private equity playbook

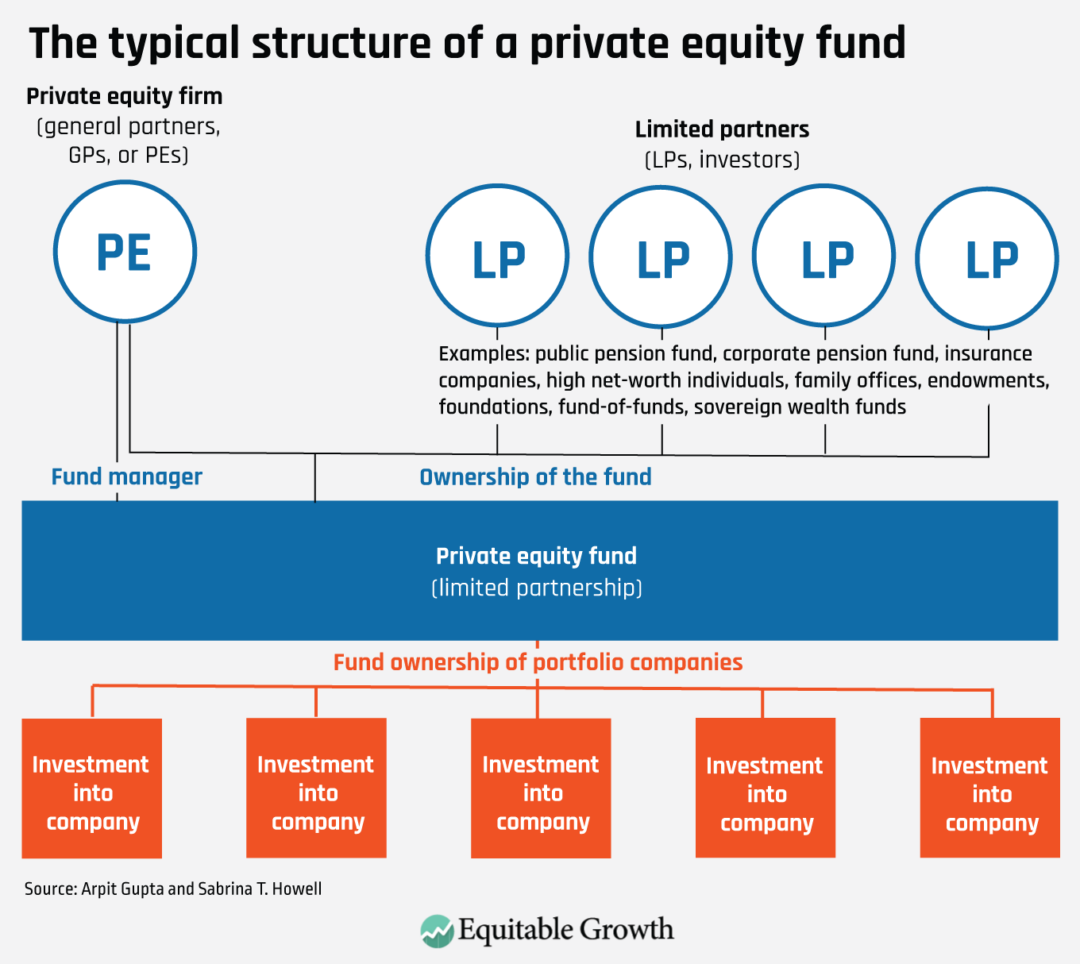

Private equity firms are financial intermediaries who connect investors, known as limited partners, with investment opportunities in the portfolio companies amassed by these firms. The private equity firm uses funds raised from these limited partners to acquire interests in portfolio companies, though the limited partners do not invest directly in the private equity firm. Rather, the managers of the private equity firm, or general partners, set up a fund vehicle, which typically has a 10-year lifespan, in which to invest the limited partners’ money and return profits. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The general partners are responsible for the day-to-day operations of the fund, including the full lifecycle of a portfolio company, from its acquisition to its sale. They identify promising targets, negotiate deals, operate the company for a period, and then sell (or otherwise liquidate) the investment to deliver stock or cash profits to themselves and the limited partners.

The investment in a portfolio company may be a partial stake, a strategy common in the “growth equity” flavor of private equity—a strategy most common among venture capital firms, a subset of the private equity sector of the U.S. financial services industry that we do not include in this analysis. When institutional investors or other financial industry players think of private equity, they expect these firms to be engaged in acquiring full ownership of companies, an approach referred to as a “buyout.”

In this report, we will focus on a central deal type in private equity: the leveraged buyout. In this type of transaction, the target firm is acquired primarily with debt financing, which is placed on the target firm’s balance sheet after its acquisition, and a small portion of equity. A useful framework for conceptualizing how private equity generates value for investors via leveraged buyouts involves three core activities:

- Financial engineering

- Governance engineering

- Operational engineering

Financial engineering refers to the use of debt—and its tax benefits—to increase private equity fund returns.2 The reliance on debt is the first of three concepts we introduce in this section that is crucial to understanding the tax policy discussion in the remainder of this report. The consequence is that private-equity-owned companies tend to have much higher leverage ratios (the proportion of debt relative to equity or overall firm value) than other types of companies. High leverage creates incentives for risk-taking behavior and necessitates the allocation of a substantial portion of the company’s cash flows to cover interest payments on that debt.3

Governance engineering refers to the common strategy of introducing new management and modifying compensation structures for executives—and, in some cases, employees—to ensure that their incentives align with those of the firm’s new ownership.4 These management changes and incentive structures reward strategies that maximize both the short-term recurring profits of heavily debt-laden companies, as well as investments to attract potential purchasers of these portfolio companies within the typical 10-year life of a private equity fund.

Operational engineering refers to those specific strategic changes that the new owners implement at the company. This can include cost-cutting, the sale of real estate assets of the acquired firms, investments in new technology, expansion of productive assets, and the downsizing of unproductive assets.5

Private equity ownership leads to different financial incentives and business strategies than other types of for-profit ownership, such as independent private firms or publicly traded firms. Compared to other for-profit owners, private equity owners have higher-powered incentives to maximize firm value. This is because the general partners are compensated through a call-option-like share of the profits, employ substantial amounts of leverage, usually aim to liquidate investments within a short timeframe, and do not have existing relationships with target firms’ other stakeholders, such as employees, customers, or suppliers.

Since most private equity funds have 10-year time horizons to return cash to investors, assets are typically held for 3–7 years. A modern private equity deal is typically not successful if the business continues as-is because of the objective to produce substantial returns on investment to general and limited partners. This means private equity firms invest with plans to motivate aggressive and short-term value-creation strategies. In contrast, a traditional business owner running the firm as a long-term operation with less leverage may prefer lower but more stable profits.

Understanding the compensation structure of general partners in a private equity firm is the second concept that is crucial for considering tax reforms for private equity. General partners are compensated primarily from the right to a share of profits, usually 20 percent, from increasing the value of portfolio companies between the time of the buyout and an exit, when the company is sold to another firm or taken public. The 20 percent share of profits is called “carried interest.”

General partners and the funds they manage also have other sources of income. First, general partners earn management fees of 1.5 percent to 3 percent of limited partners’ committed capital (usually 2 percent) each year. These fees are earned regardless of performance, and they add up.

Consider a simplified example. If a fund has $1 million in committed capital and a 10-year life with the standard 2 percent annual management fee, the general partners will earn $200,000 (or 20 percent of all the limited partners’ investment) over the life of the fund. This leaves $800,000 to invest. In order to generate a reasonable rate of return on the fund overall net of these high fees, general partners must target high returns on each deal.

In addition, the private equity fund charges the portfolio company two types of fees. The first one is a transaction fee as part of the initial purchase, which is usually about 2 percent of the transaction value. The second one is a monitoring fee, which is typically between 1 percent and 5 percent of a portfolio company’s Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization, or EBITDA, a widely used measure of a company’s financial health, with the exact percentage depending on company size. These fees do not serve an obvious incentive alignment purpose and appear to be simply ways for the fund to earn revenue.6

Finally, the third concept that is important because of its connection to tax policy is the use of real estate sales. Private equity owners often sell a portfolio company’s real estate assets shortly after the buyout to generate cash that can be returned to investors. This burdens the target firm with the additional cost of paying rent on their previous real estate assets, which becomes a regular cash outflow in addition to the new interest payment obligations.

One reason that general partners seek to sell real estate is that in many cases, especially for “old economy” firms such as retailers, the real estate is the most valuable part of the business, and by separating it, they can increase the value of the sum of both parts. A second reason is that the sale generates an early cash flow in the deal’s lifecycle, which boosts ultimate returns for the fund under a key metric by which private equity managers are evaluated, the Internal Rate of Return, or IRR, which is used to evaluate the profitability of budget decisions and real estate sales over time.

The impact of private equity ownership on their portfolio firms

A central consideration for policymakers evaluating tax subsidies for private equity investors is the extent to which private equity ownership produces positive or adverse effects on the acquired firms. There is a vast literature in financial economics on this question, most of which examines a particular outcome in a specific industry.

Our interpretation of this literature is that context matters. The incentive structure for investing in specific individual industries and then operating in them determines whether the actions that lead to profits earned by private equity investors are aligned with benefits to the customers, employees, and, in the case of subsidized industries, taxpayers. We expand on this point by briefly summarizing a small part of the literature.

One dimension upon which the literature is largely in agreement is productivity and operational efficiency. This is clear from studies starting with the pioneering work by Steven Neil Kaplan at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business,7 and more recently including work by his colleague at Chicago Steven J. Davis and his co-authors.8 This body of research details how private equity ownership has substantial positive effects on these outcomes across a broad range of sectors. This stems, in part, from better management.9 Looking at leveraged buyout acquisitions of publicly traded companies, Harvard University’s Josh Lerner and his co-authors find evidence that innovation at these companies improves post-buyout.10

When it comes to benefits to particular stakeholders such as employees and customers, the evidence is more mixed and is more sector-specific. In the context of global airports, for example, one of the co-authors of this issue brief (Sabrina T. Howell) and her co-authors show that, relative to both government and non-private-equity private ownership, private equity ownership yields large improvements to a private-equity-acquired airport, including more flights, more capacity, more passengers, and better airport amenities.11 They show that some of this reflects superior negotiation, such as extracting more revenue from airlines.

Similarly, in fast-food restaurants, Shai Bernstein at Stanford University and Albert Sheen at Harvard Business School find that private equity ownership causes health score improvements.12 And in grocery stores, Cesare Fracassi at the University of Texas at Austin, Alessandro Previtero at Indiana University, and Harvard Business School’s Sheen show that private equity owners increase product offerings and expand geographically.13

The literature finding positive effects has primarily studied settings with low information frictions (economics and finance parlance for environments in which customers can easily observe product characteristics) and little in the way of government subsidies. In contrast, there is evidence of negative effects on consumers in the contexts of nursing homes and for-profit colleges.14 Tong Liu at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business finds that private equity buyouts lead to large increases in prices and health care spending at hospitals, with no evidence of quality improvements.15

A recent report from the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, the American Antitrust Institute, and the Petris Center at the University of California, Berkeley, finds similar outcomes in the area of physician practices.16

These sectors feature severe information frictions and misaligned incentives, stemming from features such as intensive government subsidies that separate the revenue from the consumer. Quality is also opaque in these settings, leading to benefits from reallocating care resources towards marketing.

More broadly, high-powered incentives to maximize profits may be misaligned with stakeholder interest in sectors that typically have an implicit contract to contribute to some objective of social interest. Michael Ewens at Columbia University and the two co-authors of this issue brief show that private equity buyouts of local newspapers, for instance, lead to fewer reporters and editors and less content about local government—which, they document, is associated with a decline in civic engagement and, in particular, citizen participation in local elections.17 Private equity owners may be more willing to take advantage of new opportunities for value creation that would violate preexisting implicit contracts.

When it comes to employees specifically, there are also nuanced findings. Perhaps the most important body of work in this area is from Stanford University’s Davis and his co-authors John Haltiwanger at the University of Maryland, Kyle Handley at the University of California, San Diego, Ben Lipsius at the University of Michigan, Harvard’s Lerner, and Javier Miranda at Friedrich-Schiller University, and Ron Jarmin at the U.S. Census Bureau.18 These papers merge leveraged buyout data with U.S. Census Bureau data to show that private-equity-owned firms tend to increase employment at productive facilities and during periods of credit expansions but reduce employment at less productive facilities and during credit contractions. Overall, there is, if anything, a small net negative effect on employment.

Looking at other measures, Jonathan Cohn at the University of Texas at Austin and his co-authors find positive effects on workplace safety.19 And Will Gornall at the University of British Columbia and his co-authors find evidence that due to higher firm risk, employee satisfaction declines after buyouts.20

In light of this mixed literature, it is not possible to conclude that across industries, the leveraged buyout model has positive or negative effects on stakeholders besides investors. The effects depend on the sector, time, and preexisting firm characteristics. Therefore, we believe that tax policy evaluation should focus on:

- Whether high-quality, value-add deals would be affected by tax reform

- The magnitude of the benefits to taxpayers from alternative use of tax subsidies currently allocated to private equity

To conduct that kind of evaluation first requires a deeper dive into the tax advantages of private equity investing, to which we now turn.

The tax advantages of private equity investing

There are two significant tax benefits that accrue to private equity investors: taxation of carried interest at the capital gains rate of 20 percent and tax deductions from interest paid on debt. In this section, we summarize these two tax policies and then discuss other ways that private equity managers further reduce the taxes paid by their portfolio companies, funds, and general partners themselves.

Carried interest taxed at capital gains rate

Recall that general partners are compensated primarily with 20 percent of a fund’s profits, called carried interest. This income is taxed as a return on investment rather than compensation for performing services. This means that it is taxed at the long-term capital gains rate of 20 percent, rather than the higher federal income tax rate that salary-earners pay.21 The top federal income tax rate is 37 percent. The top 1 percent of earners in 2022 actually paid only 26 percent of their income in federal taxes, on average, but the Tax Foundation estimates that for the very high incomes of general partners, most income would be taxed at 35 percent or 37 percent.22

Overall, then, private equity professionals’ income tax rate is roughly half what it would be if managing assets were treated like other high-paying service professions, such as engineering software or conducting medical surgery.

The tax treatment of carried interest underwent its most recent reform in 2017 with the implementation of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. This legislation extended the minimum holding period for assets from 1 year to 3 years in order for carried interest to qualify for favorable tax treatment. While this modification diminished the advantages associated with carried interest for hedge fund general partners because hedge fund investment strategies are generally very short term, its effects on the private equity industry were relatively minimal, since holding periods in private equity usually exceed 3 years.

What are the likely tax implications of removing the provisions on carried interest? Perhaps the most direct calculation comes from the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office, which has estimated the implications of removing the carried interest provision. CBO estimates suggest that the removal of this provision would reduce the federal deficit by $5.6 billion from 2023 to 2027, and by $11.5 billion from 2023 to 2032.23

Tax and leverage: Tax shields from debt

Firms can deduct interest payments on debt from their taxable income, similar to the way some households deduct mortgage interest payments from their taxable income. This ability to deduct interest payments, while applicable to both private-equity-owned firms and all other firms, delivers a distinct benefit to private equity firms for two main reasons.

First, high debt leverage is central to value creation in leveraged buyout deals, where the acquisition of the portfolio company is financed primarily with debt that is placed on the acquired company’s balance sheet. Subsequent new debt taken on by the portfolio company can also be used for cash payouts to its private equity investors, a transaction type known as a dividend recapitalization.

This type of debt-driven financial engineering is a core competitive advantage of private equity, and optimizing tax benefits through interest deductions is a significant contributor to operational efficiency. Edith Hotchkiss at Boston College, David C. Smith at the University of Virginia, and Per Strömberg at the Stockholm School of Economics suggest that the superior ability of private equity firms to raise and manage financial leverage leads to lower rates of financial distress, relative to otherwise-similar private firms.24

Second, the strategic use of debt provides private equity firms with additional managerial advantages that facilitate operational improvements. Higher amounts of leverage further concentrate private equity firm ownership, making possible and incentivizing governance innovations at firms. This is the case because financing the deal with high amounts of leverage concentrates the residual equity ownership of the target company among a few private equity stakeholders. This financial leverage also amplifies the equity return for investors, whether positive or negative, aligning interests between the company’s management and private equity investors.

Debt also disciplines portfolio companies and encourages them to produce sufficient cash flows to repay debt. By contrast, surveys suggest that chief financial officers at publicly traded firms are often conservative with their capital structure decisions.25 This may reflect managerial myopia at public firms.26 Or it may be because firms that face high levels of equity volatility cut back on investments.27 The consequence is that the standard private equity operational strategy enables, and indeed requires, higher levels of leverage than are common in other firms.

Research on private equity buyouts highlights the role of leverage and the resulting tax benefits in influencing firm value and returns. For instance, Duke Energy Corporation’s Shuorun Guo, Edith Hotchkiss at Boston College, and Weihong Song of the University of Cincinnati note that increased leverage can create tax shields that boost returns because the company pays less corporate tax after deducting interest payments.28 And Chicago Booth’s Steven Kaplan estimates that the median value of interest and depreciation deductions from tax benefits ranges from 21 percent to 143 percent of the premium paid in management buyouts.29

More recent research by Kaplan and Strömberg suggest that reduced taxes from higher leverage can explain 10 percent to 20 percent of firm value in the 1980s, though the estimates would be lower in subsequent decades due to declining corporate tax rates.30 Also, it is possible that part of the benefit of the tax savings from leverage may be spent by general partners in greater takeover premia, reflecting greater purchase prices paid to close a transaction.31 This premia may facilitate takeovers but reflect costs and are therefore not a source of returns for these funds.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 affected these tax-shield benefits for private equity because it reduced corporate tax rates to 21 percent and reduced the deductibility of net business interest expenses to 30 percent of taxable income. As a result of these rule changes, private equity portfolio firms likely receive fewer benefits from the tax shield advantage than they did before.

Other accounting tax treatment benefits for private equity investing

There are other tax policies that benefit private equity investors. The four principal ones are fee waivers, the Qualified Business Income Deduction, depreciation allowances, and accounting rules related to real estate assets and Real Estate Investment Trusts. These accounting treatments are important for policymakers to consider as they weigh new tax policy reforms related to private equity investing. We briefly explain each of them below.

Fee waivers

Private equity firms have devised strategies to capitalize on the advantageous difference between capital gains and ordinary income tax rates. A common practice involves waiving the standard 2 percent annual management fee in exchange for a corresponding equity share of potential investment returns.32 By doing so, private equity general partners can classify even the fixed portion of their compensation as capital gains, subjecting it to lower tax rates.

For instance, Bain Capital, one of the largest private equity firms in the United States and around the world, successfully converted approximately $1 billion in management fees, which would have been subject to ordinary income tax, into fund profits taxed as capital gains—resulting in an estimated tax savings of around $200 million for its partners.33

Qualified Business Income Deduction

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 introduced the Qualified Business Income Deduction, an additional tax deduction of 20 percent from so-called passthrough business income for noncorporate owners. Passthrough income refers to income generated by a business entity that is not subject to corporate income tax at the corporate entity level. Instead, the income “passes through” to the owners of the business and is reported on their individual income tax returns. The owners are then responsible for paying income tax on their share of the business’s profits at their individual tax rates. Noncorporate owners are typically individuals paying personal tax rates.

Therefore, the new passthrough deduction provides two additional benefits to private equity firms that are unique to their status as partnerships. First, private equity firms may benefit from income flowing to them from their portfolio companies when it is designated as passthrough income. Second, high net worth individuals investing in private equity funds as limited partners may benefit from this additional deduction applied to their overall tax liability.34

Depreciation allowances

Depreciation allowances benefit private equity firms by providing tax deductions that can reduce taxable income and, consequently, lower the overall tax liability for both the private equity firm and its portfolio companies. Depreciation allowances enable a business to allocate the cost of a tangible asset, such as machinery or equipment, over its useful life. Each year, a portion of the asset’s cost is deducted as a depreciation expense, reducing the business’s taxable income.

Private equity firms often acquire and invest in portfolio companies that own tangible assets, so the depreciation deductions can lower the portfolio company’s taxable income, resulting in tax savings. By reducing the taxable income of a portfolio company, depreciation allowances can lead to lower taxes owed and therefore improve the company’s cash flow.

This additional cash flow can be used for reinvestment, debt repayment, or other operational needs, all of which can enhance the company’s value and generate higher returns for the private equity firm and its investors. While depreciation allowances apply to all firms, private equity makes more aggressive use of these provisions for two reasons. First, they allocate considerable resources to tax optimization. Second, purchasing the assets of their portfolio firms enables private equity firms to gain deductions in the form of depreciation and amortization for purchase prices.

Accelerated depreciation methods, including bonus depreciation and the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System, which allows greater accelerated depreciation for firms, thereby provide larger deductions in early years. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 allowed 100 percent bonus depreciation for qualifying assets placed in service between September 27, 2017 and December 31, 2022, and expanded Section 179 of the IRS code expensing for immediate asset expensing. These provisions further enhance tax savings for private equity firms and their investments because they provide early tax breaks, thereby improving the timing of returns and hence the internal rate of return.

Real estate benefits and Real Estate Investment Trusts

A common strategy for creating value in private equity is to separate real estate assets from other parts of acquired firms. Private equity managers earn tax benefits by spinning out real estate holdings as real estate investment trusts. A REIT is a company that owns, operates, or finances income-producing real estate and provides investors with the opportunity to invest in a diversified portfolio of properties. These trusts are required to meet specific regulatory criteria, and, in return, they receive favorable tax treatment.

Unlike traditional corporations, real estate investment trusts are not subject to double taxation at the corporate level. Instead, they pass through their taxable income to shareholders, who then pay taxes on the distributions at their individual tax rates. This pass-through structure helps to avoid the double taxation that typically applies to corporate earnings and dividends of publicly traded firms.

One example of a private equity firm taking advantage of these tax benefits by spinning out real estate holdings as a real estate investment trust is Blackstone Group’s creation of Invitation Homes. This company was created by Blackstone—a large private equity company—acquiring portfolio companies that had purchased homes. In 2017, Blackstone took Invitation Homes public as a real estate investment trust, making it one of the largest single-family rental trusts in the United States. Invitation Homes owns and manages a substantial portfolio of single-family rental properties, and, as a real estate investment trust, it benefits from the favorable tax treatment described above.

Likely impacts of reforming the tax advantages enjoyed by private equity for U.S. businesses and the broader economy and society

Would higher taxes make private equity unprofitable? There is substantial evidence that private equity persistently generates high returns, especially for the general partners themselves.35 Using data on private equity buyout funds launched between 1984 and 2015, Robert S. Harris at the University of British Columbia and his co-authors in a new research paper find average internal rates of return of 14 percent annually.36 The average multiple on invested capital—an alternative return metric that does not account for the timing of cash flows and is simply the money returned to investors divided by the money they put in—is 1.81.

Moreover, Harris and his co-authors show that private equity consistently outperformed public markets. Given these high returns, at least absent risk adjustment, it seems likely that private equity would remain a viable asset class, continuing to provide alternative investment opportunities to pension funds and other institutional investors, even if the principal tax benefits were eliminated.

An additional benefit for private equity firms lies in the illiquid nature of its investment vehicle. By not having a publicly traded price, private equity investments enable institutional investors—especially pension funds—to make leveraged investments without clear mark-to-market metrics. Recent arguments suggest that firm shareholders sometimes prefer the ability to shield investments from market pressures, resulting in an “illiquidity premium.”37 This suggests that private equity already enjoys a structural advantage over public firms based on its holding structure, limiting the need for any additional tax treatment.

There are several negative implications of subsidizing private equity via the U.S. tax code. First, it reduces revenue for public goods and services. The federal government relies on tax revenue to fund essential programs, such as health care, defense, and infrastructure. When tax revenue is diminished due to subsidies for private equity, the federal government faces budget shortfalls, leading to cuts in public services or the need to raise taxes elsewhere to make up for the lost revenue.

Second, tax subsidies for private equity can contribute to widening income and wealth inequality. A significant part of the value creation from private equity accrues to wealthy individuals. The general partners of private equity funds and any limited partners who are individuals or family-owned investment vehicles are, by and large, already extremely wealthy. Therefore, the tax benefits associated with private equity investments disproportionately benefit otherwise-taxable members of these groups.

In other words, tax benefits lead to higher returns for wealthier individuals on their investments, further increasing the wealth gap between the rich and the rest of society.38

The other recipients of returns from private equity are institutional limited partner investors such as pension funds. Private equity advocates often point to an important role for private equity in the portfolios of public pension funds, which benefit a broad array of less-wealthy individuals such as teachers and firefighters. Yet it is important to note that such institutional investors—as well as university endowments, another common institutional investor in private equity—do not pay federal taxes, and thus tax subsidies affect their returns from private equity investments only insofar as they benefit portfolio companies and thus fund returns.

It also is not certain whether the tax benefits from debt shields accrue to the funds. As mentioned above, there is evidence that the acquisition price incorporates the tax benefits of debt because private equity acquirers pay a premium relative to acquirers using less debt. This limits the degree to which this tax subsidy benefits pensioners.

Relatedly, the tax benefits of debt may distort leverage decisions, leading to higher debt for portfolio companies than might otherwise be optimal. Recall that debt in private equity leveraged buyouts is used to finance the transaction or to pay dividends to investors, not to invest in the portfolio company. This debt increases firm risk and interest payment burdens, which could alternatively be used to fund real economic activity such as employee wages or technology investment.

Finally, any degree to which fund returns are negatively affected by a decline in leverage may be offset by benefits from higher tax revenue that accrues to pension fund stakeholders, such as teachers with pension accounts. In other words, tax subsidies have opportunity costs: The government could use the tax revenue to fund publicly provided goods such as Medicare, education, or infrastructure, which may benefit the same pensioners.

Conclusion: Proposed tax reforms

Private equity firms benefit from several tax advantages that can enhance their returns and influence investment strategies. As detailed in this issue brief, these advantages include:

- The carried interest provision, which allows the income that fund managers earn for managing assets to be taxed at the much lower capital gains tax rate

- Tax deductions on interest payments

- The aggressive use of accelerated depreciation methods, which allow for larger deductions in the early years of asset ownership

- The ability to structure real estate holdings as real estate investment trusts to avoid double taxation and take advantage of pass-through tax structures

As mentioned above, the private equity industry argues that it helps to build and support entrepreneurial small businesses, and therefore merits these tax subsidies.39 Given the high returns in private equity, however, the inherently high-powered compensation structure, and the increasing evidence that operational engineering leading to higher efficiency and productivity is a major source of value creation, we do not believe that meaningful reductions in tax benefits would render the asset class unviable or dramatically reduce its benefits to institutional investors. Meanwhile, these tax benefits lead to reduced revenue for public goods and services, contribute to widening income and wealth inequality, and incentivize short-term investment strategies.

The most widely agreed-upon and most straightforward reform that would lead to greater parity in tax treatment would be to reevaluate the carried interest provision and align the taxation of carried interest with ordinary income tax rates. This would affect only the asset managers, not the portfolio companies or institutional investors (recall that returns delivered to pension funds and university endowments are not taxed at all). As general partners in private equity firms earn extremely high returns, it seems unlikely that high-quality managers would, in general, exit the industry to pursue more lucrative careers if they paid the same income taxes that other high-income white-collar service providers pay.

Improved data collection efforts are necessary to accurately measure the impact of tax advantages on private equity firms, investors, and society. Enforcement and regulatory changes would be required to implement any tax reforms, including monitoring compliance and ensuring transparency in the industry. As one example of a simple regulatory change that may help shed light on the currently opaque role of private equity in the nursing home industry, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has proposed a rule requiring nursing homes that receive Medicare or Medicaid revenue to disclose their beneficial ownership.40

More broadly, transparency regulations applicable to all firms that reduced the burden of disentangling shell companies and complex partnership layers would have many benefits, one of which would be to make it easier to measure, evaluate, and potentially reform the tax subsidies that accrue to private equity funds and their general partners.

Such transparency would also make it easier to enforce the tax laws that are already on the books. Currently, private equity firms pursue sophisiticated strategies for tax optimization, building complex layers of partnerships; since the income passes directly to potentially thousands of partners, it is very difficult for the IRS to audit the firm. For example, an article in The New York Times explains that:

While intensive examinations of large multinational companies are common, the IRS rarely conducts detailed audits of private equity firms, according to current and former agency officials. Such audits are “almost nonexistent,” said Michael Desmond, who stepped down this year as the IRS’s chief counsel. The agency “just doesn’t have the resources and expertise.”41

We support more adequate funding for the IRS to enforce existing taxes. This would yield substantial benefits in general,42 and it would enable the IRS to invest resources in the capability to audit private equity partnerships and investigate claims of tax avoidance.

It is worth noting that private equity is poised for growth as an asset class amid unprecedented fundraising, with $1.26 trillion in private equity capital raised worldwide but yet to be invested (so-called dry powder) as of early 2023, including $790 billion held in U.S.-domiciled funds. Thoughtful tax reform could promote equitable access to economic opportunities and enhance positive contributions to the economy and society.

While private equity generates high returns and contributes to economic growth, policymakers need to carefully consider the broader implications of subsidizing the industry through the U.S. tax code. Policymakers should balance the interests of private investors with the broader public interest and consider the potential positive impacts of tax reform.

—Arpit Gupta is an associate professor at New York University’s Stern School of Business. Sabrina T. Howell is an associate professor of finance at NYU Stern.

End Notes

1. See calculation in Will Gornall and others, “Do Employees Cheer for Private Equity? The Heterogeneous Effects of Buyouts on Job Quality.” Working Paper (2021), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3912230. See also PitchBook Data Inc., “ÜS PE Breakdown” (2023), available at https://files.pitchbook.com/website/files/pdf/2022_Annual_US_PE_Breakdown.pdf.

2. Steven Kaplan and Per Strömberg, “Leveraged buyouts and private equity,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 23 (1) (2009): 121–146, available at https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.23.1.121.

3. Andrew Metrick and Ayako Yasuda, “The economics of private equity funds,” Review of Financial Studies 23 (2010): 2303–341, available at https://academic.oup.com/rfs/article/23/6/2303/1569783.

4. Paul Gompers, Steven N. Kaplan, and Vladimir Mukharlyamov, “What do private equity firms say they do?” Journal of Financial Economics 121 (3) (2016): 449–476, available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304405X16301088.

5. Viral Acharya and others, “Corporate governance and value creation: Evidence from private equity,” The Review of Financial Studies 26 (2) (2013): 368–402, available at https://archive.nyu.edu/handle/2451/27878; Steven Davis and others, “Private equity, jobs, and productivity,” The American Economic Review 104 (12) (2014): 3956–3990, available at https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.104.12.3956; Ashwini Agrawal and Prasanna Tambe, “Private equity and workers’ career paths: The role of technological change,” The Review of Financial Studies 29 (9) (2016): 2455–2489, available at https://academic.oup.com/rfs/article/29/9/2455/2583670; Charlie Eaton, Sabrina T. Howell, and Constantine Yannelis, “When investor incentives and consumer interests diverge: Private equity in higher education,” The Review of Financial Studies 33 (9) (2019): 4024–2060, available at https://academic.oup.com/rfs/article/33/9/4024/5602331.

6. Metrick and Yasuda, “The economics of private equity funds.”

7. Steven Kaplan, “The effects of management buyouts on operating performance and value,” Journal of Financial Economics 24 (2) (1989): 217–254, available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0304405X89900470.

8. Steven Davis and others, “The (Heterogenous) Economic Effects of Private Equity Buyouts.” Working Paper No. 206371 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w26371.

9. Nicholas Bloom, Raffaella Sadun, and John Van Reenen, “Do private equity owned firms have better management practices?” American Economic Review 105 (5) (2015): 442–46, available at https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.p20151000.

10. Josh Lerner, Morten Sorensen, and Per Strömberg, “Private equity and long-run investment: The case of innovation,” The Journal of Finance 66 (2) (2011): 445–477, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01639.x.

11. Sabrina T. Howell and others, “All Clear for Takeoff: Evidence from Airports on the Effects of Infrastructure Privatization.” Working Paper No. 30544 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2022), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w30544.

12. Shai Bernstein and Albert Sheen, “The operational consequences of private equity buyouts: Evidence from the restaurant industry,” The Review of Financial Studies 29 (9) (2016): 2387–2418, available at https://academic.oup.com/rfs/article/29/9/2387/2583693.

13. Cesare Fracassi, Alessandro Previtero, and Albert Sheen, “Barbarians at the store? Private equity, products, and consumers,” The Journal of Finance 77 (3) (2022): 1439–1488, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jofi.13134.

14. Eaton, Howell, and Yannelis, “When investor incentives and consumer interests diverge: Private equity in higher education.” See also Atul Gupta and others, “Does private equity investment in healthcare benefit patients? Evidence from nursing homes.” Working Paper No. 28474 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w28474.

15. Tong Liu, “Bargaining with private equity: implications for hospital prices and patient welfare.” Working Paper (2021), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3896410.

16. Richard M. Scheffler and others, “Monetizing Medicine: Private Equity and Competition in Physician Practice Markets” (Washington, DC and Berkeley, CA: American Antitrust Institute, Petris Center at the School of Public Health at the University of California, Berkeley, and the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2023), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/AAI-UCB-EG_Private-Equity-I-Physician-Practice-Report_FINAL.pdf.

17. Michael Ewens, Arpit Gupta, and Sabrina T. Howell, “Local journalism under private equity ownership.” Working Paper No. 29743 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2022), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w29743.

18. Davis and others, “Private equity, jobs, and productivity.” See also Davis and others, “The (Heterogenous) Economic Effects of Private Equity Buyouts.”

19. Jonathan Cohn, Nicole Nestoriak, and Malcolm Wardlaw, “Private equity buyouts and workplace safety,” The Review of Financial Studies 34 (10) (2021): 4832–4875, available at https://academic.oup.com/rfs/article/34/10/4832/6081024.

20. Gornall and others, “Do Employees Cheer for Private Equity? The Heterogeneous Effects of Buyouts on Job Quality.”

21. Some carried interest is also subject to a 3.8 percent Medicare net investment tax. Carried interest is generally not subject to the self-employment tax.

22. Erica York, “Summary of Latest Federal Inome Tax Data 2003 Update” (Washington, DC: Tax Foundation, 2023), available at https://taxfoundation.org/publications/latest-federal-income-tax-data/; Alex Durante, “2023 tax Brackets” (Washington, DC: Tax Foundation, 2022), available at https://taxfoundation.org/publications/federal-tax-rates-and-tax-brackets/.

23. “Tax Carried Interest as Ordinary Income,” available at https://www.cbo.gov/budget-options/58694 (last accessed August 29, 2023).

24. Edith Hotchkiss, David C. Smith, and Per Strömberg, “Private Equity and the Resolution of Financial Distress,” The Review of Corporate Finance Studies 10 (4) (2021): 694–747, available at https://academic.oup.com/rcfs/article/10/4/694/6370171.

25. John Graham and Campbell Harvey, “How do CFOs make capital budgeting and capital structure decisions?” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 15 (1) (2002): 8–23, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1745-6622.2002.tb00337.x.

26. John Asker, Joan Farre-Mensa, and Alexander Ljungqvist, “Comparing the investment behavior of public and private firms.” Working Paper No. 17394 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2011), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w17394.

27. Huifeng Chang, Adrien d’Avernas, Andrea Eisfeldt, “Bonds vs. equities: Information for investment.” Working Paper (2021), available at https://www.adriendavernas.com/papers/bondsvsequities.pdf

28. Shourun Guo, Edith Hotchkiss, and Weihong Song, “Do buyouts (still) create value?” The Journal of Finance 66 (2) (2011): 479–517, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01640.x.

29. Kaplan, “The effects of management buyouts on operating performance and value.”

30. Kaplan and Strömberg, “Leveraged buyouts and private equity.”

31. Tim Jenkinson and Rüdiger Stucke, “Who benefits from the leverage in LBOs?” Working Paper (2011), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1777266.

32. Americans for Financial Reform, “Fact Sheet: Close the caried interest loophole that is a taxdodge for super-rich private equity executives” (2021), available at https://ourfinancialsecurity.org/2021/10/close-the-carried-interest-loophole-that-is-a-tax-dodge-for-super-rich-private-equity-executives/.

33. Reed Albergotti, Mark Maremont, and Gregory Zuckerman, “Firms Probed Over Tax Practice,” The Wall Street Journal, September 2, 2012, available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10000872396390443618604577626390166487030.

34. Jonathan Collett and Robert Richardt, “Impact of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act on the Private Equity Industry” (New York: CohnReznick LLP, 2018), available at https://www.cohnreznick.com/insights/impact-of-tax-cuts-jobs-act-on-private-equity-industry.

35. Robert Harris, Tim Jenkinson, and Steven N. Kaplan, “Private equity performance: What do we know?,” The Journal of Finance 69 (5) (2014): 1851–1882, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jofi.12154; David Robinson and Berk Sensoy, “Cyclicality, performance measurement, and cash flow liquidity in private equity,” Journal of Financial Economics 122 (3) (2016): 521–543, available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304405X16301593; Arthur Korteweg and Morten Sorensen, “Skill and luck in private equity performance,” Journal of Financial Economics 124 (3) (2017): 535–562, available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304405X17300430.

36. Robert Harris and others, “Has persistence persisted in private equity? Evidence from buyout and venture capital funds,” Journal of Corporate Finance 81 (102361) (2023), available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S092911992300010X.

37. Arpit Gupta and Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh, “Valuing private equity investments strip by strip,” The Journal of Finance 76 (6) (2021): 3255–3307, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jofi.13073; Cliff Asness, Tobias Moskowitz, and Lasse Pedersen, “Value and momentum everywhere,” The Journal of Finance 68 (2013): 929–985, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jofi.12021.

38. Steven N. Kaplan and Joshua Rauh, “It’s the market: The broad-based rise in the return to top talent,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27 (3) (2013): 35–56, available at https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.27.3.35.

39. American Investment Council, “Private Equity and the Treatment of Carried Interest: An Overview” (2007), available at https://www.investmentcouncil.org/private-equity-and-the-treatment-of-carried-interest-an-overview/.

40. Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Proposed Rule Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Disclosures of Ownership and Additional Disclosable Parties Information for Skilled Nursing Facilities and Nursing Facilities” (Washington, DC: Federal Register, 2023), available at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/02/15/2023-02993/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-disclosures-of-ownership-and-additional-disclosable-parties.

41. Jesse Drucker and Danny Hakim, “Private Inequity: How a Powerful Industry Conquered the Tax System,” The New York Times, June 12, 2021, available athttps://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/12/business/private-equity-taxes.html.

42. Natasha Sarin and Lawrence Summers, “Understanding the Revenue Potential of Tax Compliance Investment.” Working Paper 27571 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w27571.