The qualified small business stock exclusion overwhelmingly benefits the wealthy and should be reformed in 2025

Overview

This year’s debate over the expiring personal income and estate tax provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act provides an opportunity for reforming the qualified small business stock exclusion. The QSBS exclusion, which allows investors to avoid paying taxes on capital gains earned on the sale of early-stage stock purchases, is costly and disproportionately benefits the wealthy. It was originally enacted in 1993 and has been subsequently expanded and modified, significantly increasing its cost despite little or no evidence that it promotes economic growth or innovation.

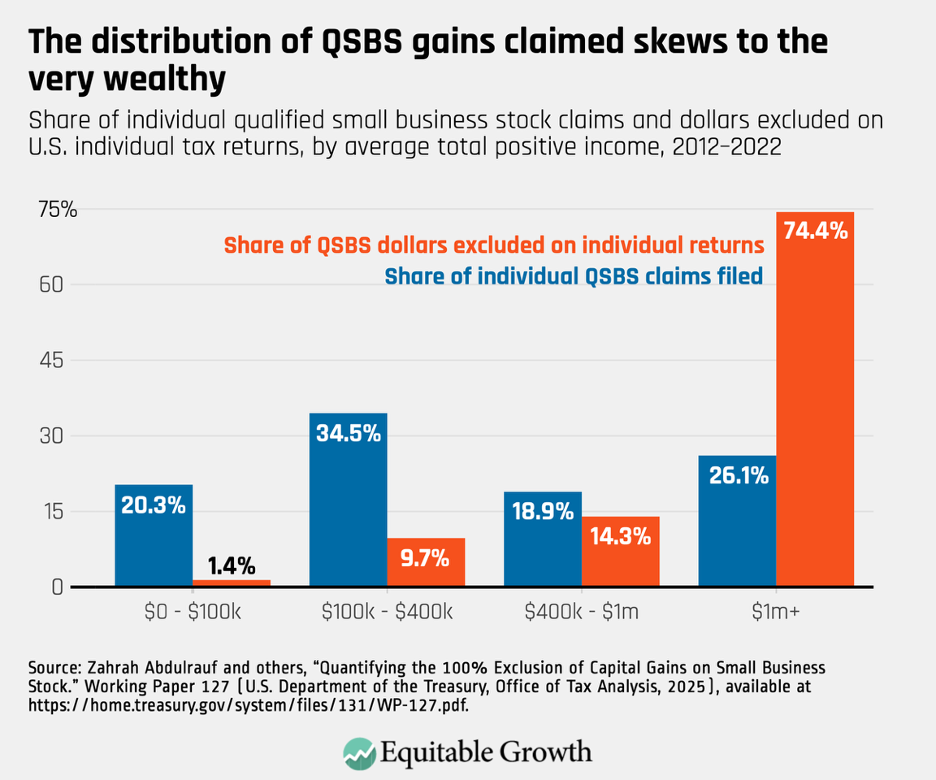

Research published by the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Tax Analysis in January 2025 quantifies the cost and identifies the beneficiaries of the QSBS exclusion.1 Prior to the release of this research, little was known about the quantity of gains qualifying for the exclusion or the characteristics of QSBS claimants. The new study finds that between 2012 and 2022—the period covered by the Treasury Department’s research—more than $152 billion in exclusion claims were filed, with the amount claimed rising significantly in recent years.2 During that period, individual filers’ claims (as opposed to those from trusts and estates) accounted for $130.6 billion of that amount. Within that group, claims by filers with total positive income of more than $1 million accounted for 26.1 percent of returns claiming the exclusion and a substantial 74.4 percent of excluded gains.3

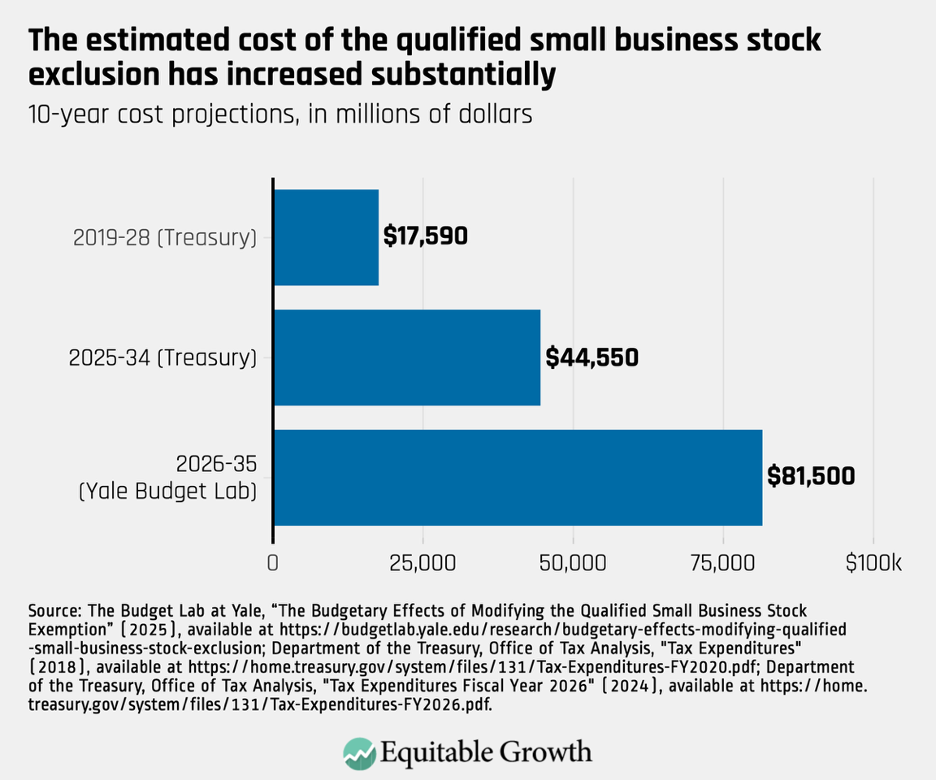

The new research builds on prior work, including a June 2023 study published by Equitable Growth.4 Taken together, the available research makes a strong case for reforming or eliminating the preferential treatment of QSBS gains. Eliminating the exclusion would raise an estimated $44.6 billion from 2025 to 2034, based on estimates by the U.S. Department of Treasury as part of its annual tax expenditure report, and $81.5 billion from 2026 to 2035, based on a new study from the Yale Budget Lab.5

In this issue brief, I will review the history of the qualified small business stock exclusion, detailing how it has expanded over time into a far more complex tool that overwhelmingly benefits the wealthiest investors. I close this issue brief with a set of recommendations that would eliminate or reduce abusive practices that allow wealthy investors to make excessively large claims. Such reforms would return billions of dollars to the U.S. Treasury Department.

What is the qualified small business stock exclusion?

The QSBS exclusion (also known as Section 1202 for the Internal Revenue Code section authorizing the exclusion) allows investors in qualified stock issued by small businesses, generally start-ups, that are organized as C corporations to exclude the gains from the sale of stock held for at least 5 years. Certain limitations apply, and the amount of excludable gains from the investment in a single company is limited to the greater of $10 million or 10 times the basis in the stock that is sold within the year.6

Individuals and trusts and estates are eligible to claim the exclusion.7 The recently released Treasury report finds that individuals accounted for about 90 percent of the unique claimants benefitting from the exclusion and about 86 percent of excluded gains, with trusts and estates accounting for the remainder.8 (See text box.)

Three types of investors typically hold qualified small business stock: founders of the company, venture capitalists and other early-stage investors, and early employees. For founders and early employees, stock grants often constitute a significant share of their compensation, promising big rewards should a business prove successful. While data on the industries issuing qualified stock are not available, the applicability of the QSBS exclusion to venture capital investments has led researchers to suggest that investors in tech start-ups are major beneficiaries.9

Intended as an incentive for investors to back high-risk, early-stage businesses, Section 1202 applies to just a small fraction of the nation’s small businesses: those organized as C-corporations.10 Less than 10 percent of U.S. small businesses are organized as C corporations, and, based on the most recent available information from the IRS, C corporations accounted for a declining share of all business income.11

The history of the qualified small business stock exclusion

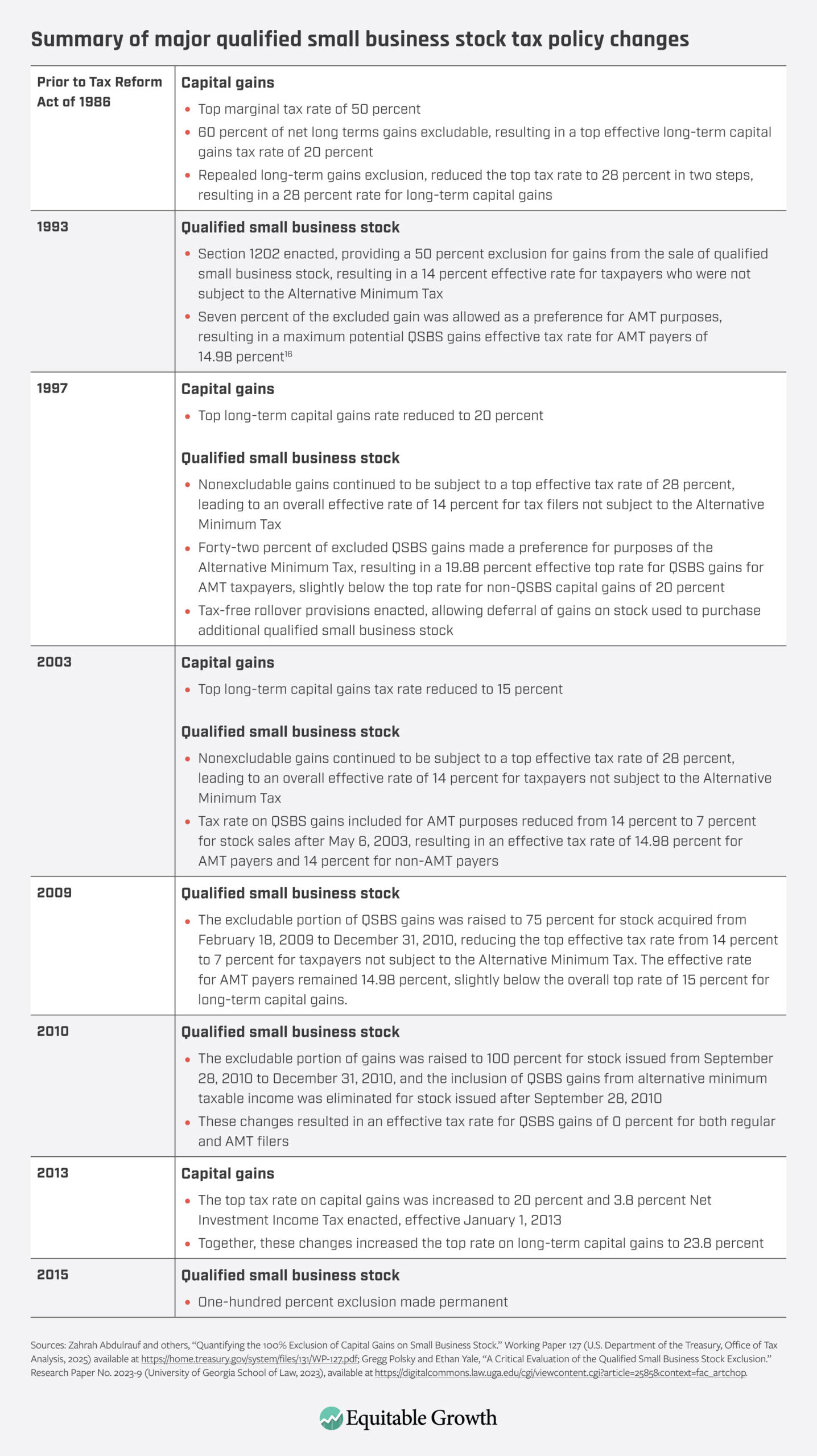

The QSBS exclusion was enacted in 1993 with the aim of spurring investment in start-up businesses. It came on the heels of the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which eliminated the ability to exclude 60 percent of all long-term capital gains, raising concern that investors would be unwilling to take the risk of investing in start-up businesses.12 At the time of enactment, the QSBS exclusion allowed investors to exclude 50 percent of the gains earned on the sale of stock held for at least 5 years that also met other specified conditions.13 Over time, the exclusion has been modified and expanded.

The 1997 and 2003 reductions in the top tax rate that applied to all long-term gains narrowed the gap between the effective top rate on all gains and that on qualified small business stock.14 Small business stock advocates pushed to widen the differential to increase the relative benefits of the QSBS exclusion. The law now allows for the full exclusion of the excess of qualified gains on stock issued after September 28, 2010.15 (See Table 1.)

Table 116

Most QSBS claims benefit the very wealthy

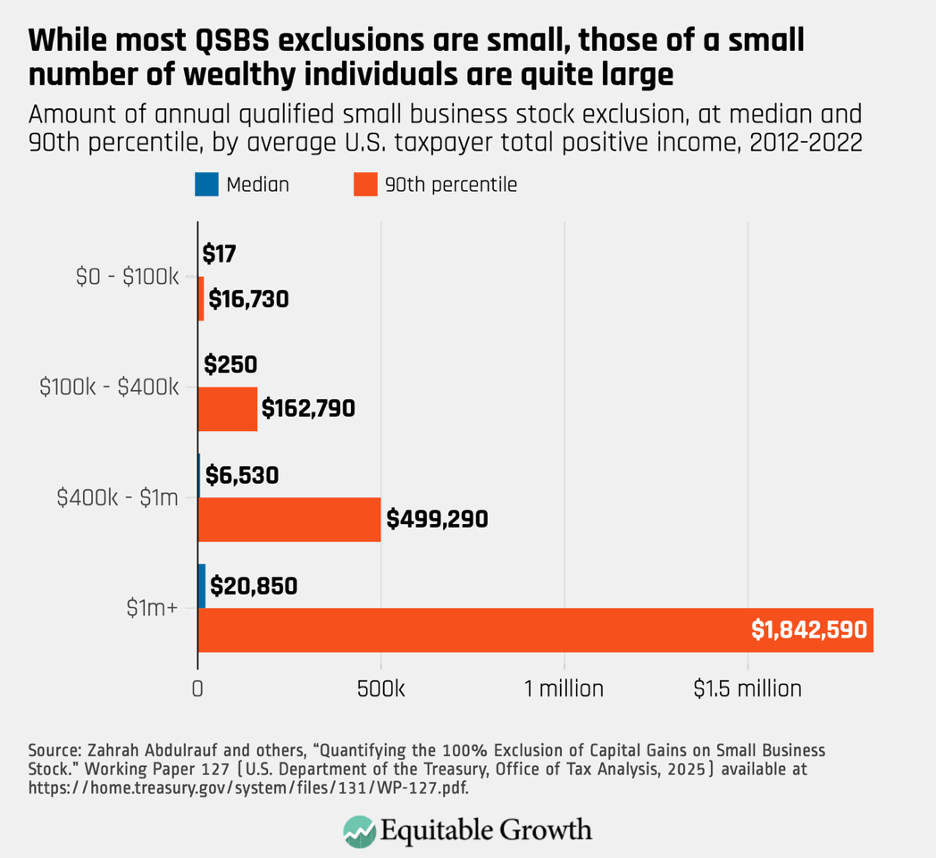

The new study published by the U.S. Department of the Treasury examined 11 years of tax returns claiming QSBS exclusions.17 The authors find that the wealthiest tax filers—those with total positive incomes of more than $1 million—accounted for roughly three-quarters of QSBS gains excluded on individual tax returns during the period examined, but only about one-quarter of the claims filed. Meanwhile, 1 out of 5 individual tax returns claiming the exclusion reported incomes up to $100,000, with these returns accounting for just 1.4 percent of actual excluded gains. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

This disparity reflects a dramatic difference in the amount of excluded gains claimed, with a median claim of $20,850 for filers with incomes of more than $1 million, or 1,226 times the median claim of filers with incomes less than $100,000. The very largest claims—those at the 90th percentile filed by claimants with incomes of more than $1 million—averaged $1.84 million. This would translate into a tax reduction of $438,536 for a claimant taxed at a rate of 23.8 percent (the 20 percent long-term capital gains tax rate plus the 3.8 percent net investment income tax rate).18 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

The QSBS exclusion contributes to the rising share of capital gains that go untaxed

Recent estimates suggest that a large share—potentially as much as one-third to one-half of all income from capital gains—goes forever untaxed due a number of preferential rates, exclusions, and other special treatment.19 Similarly, research finds that more than half of the estates of the wealthiest decedents—those with more than $100 million in assets—comes from unrealized, and thus untaxed, capital gains.20

While the QSBS exclusion accounts for a relatively small share of all realized capital gains—1.5 percent of those reported on tax returns between 2012 and 2022, according to the conservative estimates from the recent Treasury Department study—the 100 percent exclusion and the rise in excluded gains is significant both in absolute terms and as a percentage of all capital gains in the period studied.21

The current structure of the QSBS exclusion can be gamed by investors

While a company must have assets valued at no more than $50 million at the time the stock qualifying for the exclusion is issued, qualified stock maintains that status no matter how large the business grows.22 Moreover, although the maximum excludable gain is limited to the greater of $10 million or 10 times the claimant’s basis in the stock, the ability to gift stock to friends and family or to a trust expands the benefits of QSBS status.

An early-stage investor, for example, could establish trusts for their heirs to shelter additional gains from taxation.23 Similarly, the total gain excluded by claimants’ participation in an investment partnership, such as a venture capital fund, could exceed the $10 million-or-10-times basis limit. Consider, for example, a venture capital fund with more than 50 investors that makes a $50 million investment. In this example, more than $500 million in gains could well be excluded if the total number of general partners in the venture capital fund making the qualified investment is greater than 50.24

Other areas that leave the asset limit open to abuse include contributions of intellectual capital, made without compensation, by a founder to a start-up and self-created goodwill. In each case, the value to the company for tax purposes would be zero, while the economic value to the firm could be substantial.

Venture capital fund managers are likely to be one of the largest classes of QSBS exclusion beneficiaries.25 In brief, individual fund managers typically invest a portion of the fund’s working capital in the firms in which they invest. The venture capital fund managers receive a proportionate share of the gains on this investment when the stock is sold.

Fund managers then receive a “second bite of the apple” with respect to gains they receive as carried interest, partial compensation for management of the investment fund. The carried interest payment, typically equal to 20 percent of the gains earned by the venture capital fund, allows managers to benefit each time the fund sells a stock eligible for the QSBS exclusion. This exacerbates the effect of the controversial carried interest loophole, which provides preferential treatment to venture capital and private equity fund managers by treating a portion of their management fee as an investment, rather than as wage and salary income.26

More recently, investment advisors have marketed structures aimed at allowing QSBS owners to avoid the 5-year holding period and/or increase the amount of tax-free gains.27 These firms, for example, market investment pools that allow gain holders who sell before the end of a 5-year holding period to roll over the gain from a sale and escape the payment of tax or to multiply excludable gains by stacking a series of trusts. Others advise investors on how to set up a QSBS qualified business to use as a gain-sheltering investment.28(See illustration below.)

Advertisement for strategies to avoid QSBS anti-abuse provisions

Source: “QSBSrollover.com: Home page,” available at https://www.qsbsrollover.com, last accessed January 2025.

The rising volume of QSBS claims has led to an increase in the provision’s estimated cost. The U.S. Treasury Department’s FY 2020 Tax Expenditure report estimated a 10-year cost of $17.6 billion.29 By 2024, the department projected a 10-year cost of $44.6 billion, and a recent study by the Yale Budget Lab estimated the 10-year cost from 2026–2035 to be $81.5 billion.30 (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

The actual cost could be much higher than these projections, considering the increase in the value of initial public offerings and that accurate forecasting is complicated by the lack of information reporting or certification requirements imposed on corporations that issue stock used to qualify for the QSBS exclusion.31

Does the QSBS exclusion promote economic growth and innovation?

The original intent of the QSBS exclusion was to encourage investment in small businesses that might otherwise have difficulty attracting capital.32Limited research suggests that the exclusion results in a modest increase in early-stage funding but at a relatively high cost. Moreover, a large share of the benefit—approximately one-third—accrues to investors who are disproportionately very wealthy and not to the small businesses.33

The dramatic expansion of the venture capital sector in recent years draws into question whether the conditions that led to the enactment of the exclusion still apply today. Some researchers argue that there is now a “glut” of venture capital available and that investable funds exceed quality investments.34These critics charge that the QSBS exclusion provides a costly windfall that narrowly benefits extraordinarily wealthy investors.

Options for reforming the qualified small business stock exclusion

Congressional debate over the expiration of the personal income and estate tax provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act provides an opportunity to eliminate or reform the QSBS exclusion. As discussed above, eliminating the exclusion would raise an estimated $44.6 billion from 2025–2034, based on 10-year cost projections of the provision by the U.S. Department of the Treasury, and $81.5 billion from 2026–2035, based on a new study from the Yale Budget Lab.35

Short of repealing the exclusion, options for reform include:

- Limiting the size of the QSBS exclusion available to high-income individuals: The U.S. Congress previously considered reducing the percentage of excludable gains to 50 percent for individuals with incomes greater than $400,000 and for trusts.36 A 2021 Joint Committee on Taxation estimate projected savings of $5.7 billion from imposing such a limit over 10 years.37The exclusion could also be phased out entirely for those incomes in excess of $400,000. Implicitly, a limitation on excludable gains would also subject included amounts as income for purposes of the Net Investment Income Tax, consistent with the treatment of other investment-related income.

- Limiting the use of multiple stacked trusts to increase the volume of excluded QSBS gains and to minimize the amount of taxable gains: This could be accomplished by establishing a lookback rule applying to transactions with multiple trusts.38

- Eliminating QSBS gains as a preference item for the purposes of calculating Alternative Minimum Tax liability: Requiring these gains to be included would help ensure that the Alternative Minimum Tax provides a meaningful backstop, so that the wealthy pay at least a minimum level of tax on the income they receive.

- Extending the holding period for qualified small business stock and limiting the exclusion for stock that is held for shorter periods of time: A recent analysis by the Yale Budget Lab projected that requiring stock to be held for 7 years to qualify for a 100 percent QSBS exclusion, while limiting the exclusion to 50 percent for stock held for 5 years and 75 percent for stock held for 6 years, would raise about $8.5 billion over the 10-year budget forecasting window.39

- Limit QSBS treatment to corporations that have raised less than $10 million in equity capital: Imposing such a capital ceiling would limit QSBS treatment to early-stage start-ups that have yet to demonstrate an ability to tap into unsubsidized forms of capital.

- Eliminate the tax-free rollover provision: Under current law, taxpayers avoid paying taxes on gains received from the sale of qualified small business stock held for at least 6 months if they are used to purchase replacement qualified small business stocks. The rollover provision does nothing to increase the total amount of capital flowing to start-up firms and has spawned abuse and provides opportunities for investors to circumvent the 5-year holding requirement and other protections.

- Issuing regulations to clarify how companies’ valuation is calculated for the purposes of determining whether stock is “qualified”: Areas in need of clarification include limits on the use of bonus depreciation when determining whether a company meets the $50 million asset threshold.40

- Apply the limit on excludable gains to investments made by partnerships at the partnership, rather than partner, level: This would prevent the use of partnership structures to evade the $10 million-or-10-times-basis cap on excludable QSBS gains.

- Targeting the QSBS exclusion to truly small businesses, such as by substituting a limit of no more than $10 million of total annual income for the current $50 million asset test: A limit at this level would be consistent with the existing Treasury Department definition of a small business.41

- Imposing reporting requirements so that policymakers and researchers can better understand the value of outstanding excludable gains and the characteristics of QSBS exclusion claimants: A reporting requirement could be linked to a pre-certification of eligibility requirement, which could help reduce potential noncompliance.

Conclusion

The 2025 tax debate offers an opportunity for the U.S. Congress to revisit and reform the QSBS exclusion. As the new Treasury data demonstrate, the exclusion overwhelmingly benefits the wealthy and has risen in cost over time. The rising cost of the QSBS exclusion, coupled with well-documented opportunities for its abuse, call for scrutiny as the tax debate moves forward in 2025.

The author wishes to thank David Mitchell, Gregg Polsky, and Manoj Viswanathan for their very helpful comments and suggestions.

About the author

Jean Ross is an economist and tax policy analyst and the principal of Jean Ross Policy | Strategy. She holds a M.C.P from the University of California, Berkeley in regional economics and economic development.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!

End Notes

1. Zahrah Abdulrauf and others, “Quantifying the 100% Exclusion of Capital Gains on Small Business Stock.” Working Paper 127 (U.S. Department of the Treasury, Office of Tax Analysis, 2025), available at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/WP-127.pdf.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Manoj Viswanathan, “Money for Nothing” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2023), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/060823-QSBS-ib.pdf.

5. Department of the Treasury, Office of Tax Analysis, “Tax Expenditures Fiscal Year 2026” (2024), available at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/Tax-Expenditures-FY2026.pdf?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email; The Budget Lab at Yale, “The Budgetary Effects of Modifying the Qualified Small Business Stock Exclusion” (2025), available at https://budgetlab.yale.edu/research/budgetary-effects-modifying-qualified-small-business-stock-exclusion.

6. Investors can invest in multiple companies. See Manoj Viswanathan, “The Qualified Small Business Stock Exclusion: How Startup Shareholders Get $10 Million (Or More) Tax-Free,” Columbia Law Review Forum 120 (1) (2020), available at https://columbialawreview.org/content/the-qualified-small-business-stock-exclusion-how-startup-shareholders-get-10-million-or-more-tax-free/; Gregg Polsky and Ethan Yale, “A Critical Evaluation of the Qualified Small Business Stock Exclusion.” Research Paper No. 2023-9 (University of Georgia School of Law, 2023), available at https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2585&context=fac_artchop.

7. Abdulrauf and others, “Quantifying the 100% Exclusion of Capital Gains on Small Business Stock.”

8. Ibid.

9. Viswanathan, “The Qualified Small Business Stock Exclusion: How Startup Shareholders Get $10 Million (Or More) Tax-Free.”

10. Small businesses are defined as those with no more than $10 million of annual revenue. See Viswanathan, “Money for Nothing”; Cornell Law School, Legal Information Institute, “Title 26 U.S. Code § 1202 – Partial exclusion for gain from certain small business stock,” available at https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/1202. Moreover, as noted in the textbox, businesses in a number of industries are ineligible for the QSBS exclusion.

11. Viswanathan, “The Qualified Small Business Stock Exclusion: How Startup Shareholders Get $10 Million (Or More) Tax-Free”; Jean Ross, “The 2017 Tax Bill’s Pass-Through Deduction Largely Favors the Wealthy and Encourages Gaming of the Tax Code” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2024), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/the-2017-tax-bills-pass-through-deduction-largely-favors-the-wealthy-and-encourages-gaming-of-the-tax-code/.

12. Abdulrauf and others, “Quantifying the 100% Exclusion of Capital Gains on Small Business Stock.”

13. Polsky and Yale, “A Critical Evaluation of the Qualified Small Business Stock Exclusion”; Abdulrauf and others, “Quantifying the 100% Exclusion of Capital Gains on Small Business Stock.”

14. Abdulrauf and others, “Quantifying the 100% Exclusion of Capital Gains on Small Business Stock.” The 2003 reduction to 15 percent was reversed in 2013.

15. Abdulrauf and others, “Quantifying the 100% Exclusion of Capital Gains on Small Business Stock.”

16. The Alternative Minimum Tax limits the ability of high economic-income taxpayers to claim certain exclusions, credits, and deductions. It is designed to ensure that those individuals pay at least a minimum amount of tax. See Internal Revenue Service, “Topic no, 556, Alternative Minimum Tax” (last updated November 2024), available at https://www.irs.gov/taxtopics/tc556.

17. Abdulrauf and others, “Quantifying the 100% Exclusion of Capital Gains on Small Business Stock.”

18. Ibid.

19. See, for example, Jenny Bourne and others, “More Than They Realize: The Income of the Wealthy and the Piketty Thesis,” National Tax Journal 71(2)(2018), available at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/estatestaxbourne.pdf; Congressional Research Service, “Capital Gains Taxes: An Overview of the Issues” (2022), available at https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47113/2; James M. Poterba and Scott Weisbenner, “The Distributional Burden of Taxing Estates and Unrealized Capital Gains at the Time of Death.” Working Paper 7811 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2000) available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=237133.

20. Chuck Marr, Samantha Jacoby, and Kathleen Bryant, “Substantial Income of Wealthy Households Escapes Annual Taxation Or Enjoys Special Tax Breaks Reform Is Needed” (Washington: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2019) available at https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/11-13-19tax.pdf.

21. The researchers note that their “estimates represent a lower bound on the total amount of exclusions claimed under Section 1202.” See Abdulrauf and others, “Quantifying the 100% Exclusion of Capital Gains on Small Business Stock.”

22. Polsky and Yale, “A Critical Evaluation of the Qualified Small Business Stock Exclusion.”

23. Viswanathan, “Money for Nothing.”

24. Viswanathan, “The Qualified Small Business Stock Exclusion: How Startup Shareholders Get $10 Million (Or More) Tax-Free.”

25. For a more detailed discussion of issues related to qualified small business stock and venture capital investments, see Polsky and Yale, “A Critical Evaluation of the Qualified Small Business Stock Exclusion.”

26. For a discussion of the taxation of carried interest, see Congressional Research Service, “Taxation of Carried Interest” (2022), available at https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46447.

27. “QSBSrollover.com: Home page,” available at https://www.qsbsrollover.com, last accessed January 2025.

28. See, for example, ibid.

29. U.S. Department of the Treasury, Office of Tax Analysis, “Tax Expenditures.” (2018), available at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/Tax-Expenditures-FY2020.pdf.

30. U.S. Department of the Treasury, Office of Tax Analysis, “Tax Expenditures Fiscal Year 2026”; The Budget Lab at Yale, “The Budgetary Effects of Modifying the Qualified Small Business Stock Exclusion.”

31. Abdulrauf and others, “Quantifying the 100% Exclusion of Capital Gains on Small Business Stock.”

32. Polsky and Yale, “A Critical Evaluation of the Qualified Small Business Stock Exclusion.”

33. Alexander S. Edwards and Maximilian Todtenhaupt, “Capital Gains Taxation and Funding for Start-Ups” (2018), available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3265385.

34. Polsky and Yale, “A Critical Evaluation of the Qualified Small Business Stock Exclusion”; Jeffrey Grabow, “AI funding kicks into overdrive in Q4 2024” (New York: EY, 2025), available at https://www.ey.com/en_us/insights/growth/venture-capital-investment-trends#:~:text=VC%2Dbacked%20companies%20raised%20over,60%25%20of%20all%20Q4%20fundraising.

35. U.S. Department of the Treasury, Office of Tax Analysis, “Tax Expenditures Fiscal Year 2026”; The Budget Lab at Yale, “The Budgetary Effects of Modifying the Qualified Small Business Stock Exclusion.”

36. Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, H.R. 5376, 117th Cong. (November 19, 2021), available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5376/text/eh.

37. Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects Of The Revenue Provisions Of Title XIII – Committee On Ways And Means, Of H.R. 5376, The ‘Build Back Better Act,’ As Passed By The House Of Representatives” (2021), available at https://www.jct.gov/publications/2021/jcx-46-21/. In light of estimates showing an increased cost of the QSBS exclusion, the savings from such a limit could be substantially larger.

38. The Tax Law Center at NYU Law, “QSBS and multiple trusts planning” (n.d.), available at https://taxlawcenter.org/base-broadeners/base-broadener/qualified-small-business-stock-qsbs-and-multiple-trusts-planning/.

39. The Budget Lab at Yale, “The Budgetary Effects of Modifying the Qualified Small Business Stock Exclusion.”

40. Viswanathan, “Money for Nothing.”

41. Richard Prisinzano and others, “Methodology to Identify Small Businesses.” Technical Paper 4 (U.S. Department of the Treasury, Office of Tax Analysis, 2016), available at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/TP4-Update.pdf.