The coronavirus pandemic requires a wartime commitment for essential workers’ access to childcare

The current public health and economic crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic is reshaping society and the U.S. labor force in ways not experienced since World War II. Factories that previously made luxury products are being repurposed to produce medical and sanitation supplies. Retired doctors and nurses are re-enlisting in the fight against COVID-19, the disease spread by the new coronavirus. Meanwhile, hundreds of millions of U.S. workers have been told to remain at home under public health ordinances, drawing comparisons to London during the blitz.

This rapid restructuring of the U.S. workforce is posing another challenge reminiscent of World War II: the need to provide essential workers with the childcare services required to efficiently protect and support families. These frontline workers, including all the nurses and doctors, grocery store and pharmacy workers, food processing and restaurant carry-out staff, truck delivery and taxicab drivers, transit workers, and first responders who are keeping the rest of us safe, fed, and transported need childcare support more than ever. Bold, wartime thinking was required to meet the childcare needs of the 1940s. Similar efforts may be warranted today.

The nation’s childcare system is undergoing simultaneous supply- and demand-side shocks. On the supply side, several states have ordered the vast majority of childcare centers closed while some advocates are calling for further shutdowns to help slow the spread of the new coronavirus. Even prior to the pandemic, the childcare industry was in a crisis with dire economic implications. Most childcare businesses are very small, with 44 percent of providers either self-employed or working for a private household. Profit margins in the industry are often razor thin, and the median wage for caregivers is only $11 an hour. These types of low-wage workers are at particularly high economic risk during the coronavirus recession.

On the demand side, parents who are still employed are now telecommuting and trying to juggle childcare, homeschooling, and their own day jobs. The role of the childcare industry in supporting the U.S. economy by freeing up parents’ time to engage in work has rarely been clearer. While many frontline workers still need access to childcare, the millions of Americans working from home or unemployed and looking for work have caused demand for childcare services, and the ability to pay for them, to rapidly decline.

As access, demand, and money for childcare has plummeted in recent weeks, there is significant concern as to whether the industry can weather the ongoing crisis. A recent member survey by the National Association for the Education of Young Children finds that 30 percent of childcare providers could not survive a closure any longer than two weeks, and 49 percent are already losing income because families cannot afford care. This survey was conducted before the recent jaw-dropping spike in unemployment—further signs of a demand shock—was fully understood.

Just as the stability of the childcare industry is most precarious, first responders and other essential workers fighting COVID-19 need it more than ever. A recent analysis by the Center for Economic and Policy Research shows that more than one-third of essential workers—those employed by grocery, convenience, and drug stores; public transit; shipping and logistics; cleaning services; healthcare; and childcare and social services—have a child at home. Nearly one-quarter earn less than 200 percent of the poverty line, meaning any childcare they could find would be difficult to afford without assistance.

Nationally, nearly 100,000 public schools—a massive source of free care (and education) for children during the day—are closed, further complicating essential workers’ childcare needs. While the Families First Coronavirus Response Act—the second congressional action signed into law by President Donald Trump early last month—provides emergency caregiving leave for some parents dealing with these school closures, healthcare providers and first responders were excluded from this benefit.

Unfortunately, recent U.S. Department of Labor regulations adopt a very broad definition of workers who belong in these categories. The new rules carve out of the coverage many parents who should reasonably access these leave benefits.

Learning from the history of an earlier wartime commitment

There is no direct historical comparison for this rapid, complex shift in America’s caregiving needs. The closest may be the sudden expansion of women’s labor force participation in the 1940s as part of the nation’s WWII effort. Among women whose husbands were in the U.S. armed forces, labor force participation shot from 15.6 percent in 1940 to 52.5 percent in 1944. This sudden shift in the labor force required a reorganization of home life and childcare arrangements when the modern childcare industry was still in its infancy.

The public response, as described in historian William M. Tuttle Jr.’s review of 1940s childcare policy, was a mix of moral panic and uncertainty in the country’s ability to meet this need. For the first time, “latchkey” or “door key” kids were part of the national conversation. Stories filled newspapers and congressional hearing rooms of children locked in cars and chained to trailers while mothers went to work with no one home to watch their children. While some of these stories were certainly apocryphal, they spoke to a new source of national anxiety.

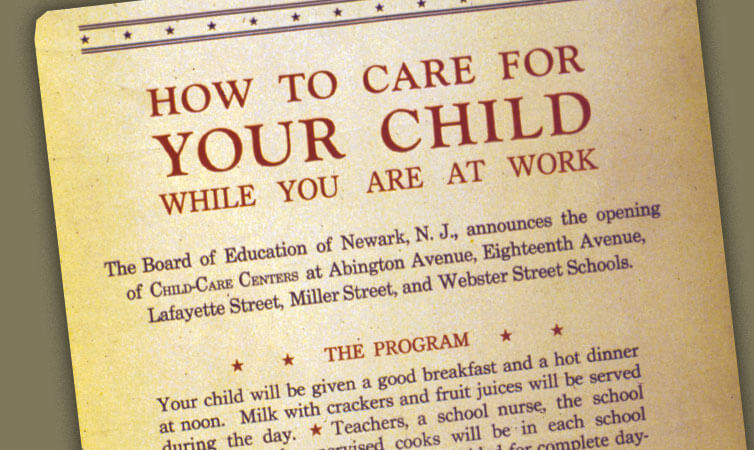

In response to these concerns, advocates and organizers engaged in practical, grassroots planning to meet this new need, including calls for a national nursery school system. Tuttle Jr.’s review describes how, in the following years, the country embarked on a bold public and private expansion of childcare options to support mothers involved in the war effort.

In many respects, the childcare system that emerged in the 1940s looked like the patchwork system of today. Most mothers relied on informal caregiving from family members, and private childcare centers opened across the country—often operated by firms engaged in wartime production seeking to attract new female workers. By 1942, the Children’s Bureau (now under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) began issuing local grants for Extended School Services, which provided afternoon care for school-age children using communities’ existing infrastructure.

But the federal government’s boldest action, and biggest departure from today’s childcare system, was a short-lived experiment with universal, federally funded childcare centers. Using funds from the Defense Housing and Community Facilities and Services Act of 1940—popularly known as the Lanham Act—the U.S. government funded childcare centers in more than 650 communities with defense industries across the country. Families were eligible to send their children to these Lanham Act centers, regardless of income, for a small fee. Adjusting for inflation, the cost to families was less than $11 per day.

Lanham Act centers were only widely available from 1943 to 1946, and not every child who needed care had access to a center. When soldiers, sailors, and marines returned home from the war, women were once again pushed out of the workforce, and the perceived need for childcare went with them. Despite the limitations of the program, a 2013 study identified both short- and long-term benefits. Using U.S. census data, Arizona State University researcher Chris Herbst found that communities with access to high levels of Lanham center funding were associated with greater labor force participation for women and improved education and employment outcomes for their children in the decades following the war.

It is important to note that the Lanham Act was not designed as a childcare bill. It was a public works initiative intended to help local communities shore up the housing and infrastructure needs for communities with defense-related industrial production and for those engaged in the national defense. The federal government, however, understood that parents could not productively contribute to the war effort if they did not have someone to care for their children. Childcare was recognized as just as important as a roof overhead or a road connecting homes to factories, and the government responded accordingly.

This wartime commitment to childcare is critical in the current war against COVID-19, particularly at a time when having grandparents babysit is no longer a safe option and school-based care is temporarily closed. While a universal, Lanham-type effort may not be feasible or appropriate during the current pandemic, governments across the country are not out of options.

Fighting the coronavirus pandemic today

At the state and local level, some jurisdictions hit hardest by the coronavirus are finding creative solutions to the childcare crisis. Vermont has pledged to cover providers’ forgone tuition costs. Several states are allowing some centers to provide emergency childcare for essential workers. New York City has also opened around 100 Regional Enrichment Centers providing early childcare and K–12 education for the children of designated employees. At these centers, class sizes are kept very small to reduce the risk of infection.

Unfortunately, early data suggests that few eligible families are currently receiving these services. As these programs are still new, enrollment could rise as governments resolve administrative hurdles and engage in more public outreach about these options. Still, parents may be concerned about the risk of viral transmission at these centers, which is why some experts have called for an expansion in funding for one-on-one home-based care and better guidance for public health officials.

Even in jurisdictions providing emergency childcare, many essential workers are left out. In New York City, for example, Regional Enrichment Centers are open to the children of healthcare workers, first responders, transit workers, and other essential city employees. This is a valuable resource for these families, but the program should be expanded to support other frontline workers such as delivery drivers, grocery store staff, and other private employees offering nutrition, care, and comfort to individuals staying home.

So far, the federal government has provided limited aid to the childcare industry. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act, enacted late last month, funnels $3.5 billion to providers through emergency funding to the Child Care and Development Block Grant. Because most childcare providers are small businesses, they are also eligible for the Paycheck Protection Program designed to keep staff on payroll during the public health crisis. Unfortunately, experts doubt that underresourced providers will have fair access to the funds or that the program can alleviate the long-term challenges facing the childcare industry.

The CARES Act was a good start, but the aid it provides is far short of the $50 billion in flexible funding advocates estimate is necessary to see the industry though the coronavirus recession. Childcare centers and home-based providers need additional support covering their operating costs during the crisis. Tuition assistance should be expanded to more essential workers who need to secure childcare outside of school. Finally, the childcare workforce needs better protection, including personal protective equipment, hazard pay, and resources for finding substitute caregivers when necessary.

Any relief must also include protection for immigrant families, documented or otherwise. More than 17 percent of frontline workers are foreign born, and, currently, many immigrants are left out of coronavirus relief efforts. Workers with an Individual Taxpayer Identification number (as opposed to a Social Security number), undocumented workers, and mixed-status families will not be eligible for the forthcoming stimulus rebates. This is money that could have gone to securing childcare. With 1 in 5 childcare workers being foreign born, protecting the immigrant community is a necessity in any effort to protect the childcare industry.

Fortunately, federal policymakers still have an opportunity to engage in a bold wartime effort to support childcare. Congress and the White House are currently eyeing an additional legislative package that could expand some of the provisions in the CARES Act and provide additional economic aid. Incorporating significant and creative childcare investments in the fourth coronavirus package will be critical in protecting the childcare industry during this crisis and ensuring that frontline workers can productively fight the new coronavirus.

Congress must also plan for a “postwar” period. Shoring up the childcare industry now will help guarantee that it is there to aid in the coronavirus recession and economic recovery once the public health crisis ends. Research shows that access and affordability of childcare impact labor force participation. If childcare services are not readily available when the crisis subsides, then it could slow families’ return to work, particularly if social distancing practices are relaxed in such a way that grandparents and other vulnerable caregivers are still encouraged to self-isolate. In order to prepare the U.S. economy for an economic recovery, the childcare industry may need to have capacity that exceeds even pre-pandemic levels.

Nearly 50 years after the end of the war, Tuttle Jr. closed his review of World War II childcare policy with this critique:

The tragedy of the Second World War experience is how little carry-over value it had in the decades since 1945, even in the face of the country’s mounting need for [childcare].

In the next few weeks, Congress must do what it can to ensure that historians studying our own coronavirus experience cannot say the same.