Testimony by Shayna Strom before the Senate Budget Committee

Shayna Strom

Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Testimony before the Senate Budget Committee

Hearing on “Reducing Inequality, Fueling Growth:

How Public Investment Promotes Prosperity for All”

September 20, 2023

Introduction

Chairman Whitehouse, Ranking Member Grassley, and members of the committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify today.

I am the President and CEO of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, a nonprofit research and grantmaking organization dedicated to advancing evidence-backed ideas and policies that promote strong, stable, and broad-based economic growth. Since 2013, Equitable Growth has provided more than $9.6 million in grants to more than 350 academic researchers aiming to understand how economic inequality—in all its forms—affects growth and stability.

Today, I want to make two important points: First, high levels of economic inequality are detrimental not only to the millions of people left behind economically, but they are also detrimental to strong, stable, and broad based economic growth. Second, the economic policies pursued by the federal government since the start of the pandemic—especially significant public investments and income supports—had a notably positive impact on many of those obstacles to growth and have resulted in strong economic outcomes.

Historical Trends in Inequality

For context, I want to start by discussing historical trends in inequality. According to one estimate, 70 percent of national income in 1979 was earned by the bottom 90 percent of individuals. But by 2019, the share of income earned by that group had fallen by 9 percentage points, to just 61 percent of national income. Nine percentage points of all national income represents an enormous transfer of income from working- and middle-class families to those at the top.

This rapid increase in income inequality had negative impacts on Americans who were left behind. Economists studying generational mobility find that a child born in 1940 had a 90 percent chance to earn more income than their parents by the time they were age 30. But a child born in 1980, whose adult earnings are observed in 2010, had just a 50 percent chance to do the same. Contrary to the ideal of the American Dream, it is now more difficult for a young person to achieve upward mobility in the United States than it is in some high-income European countries.

Inequality Harms Economic Growth

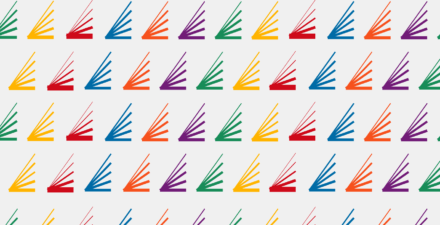

Unfortunately, the fortunes of the rich did not trickle down as promised but simply resulted in stagnant pay for everyone else. Average economic growth was lower in the recent decades when inequality was increasing than it was in recent decades when inequality was falling. (See Figure 1.) This finding has been corroborated by evidence from other historical and international examples. In the international context, researchers associated with the IMF find that lower inequality is positively related to economic growth. The same researchers additionally find that nations with lower inequality enjoy longer spells of growth, leading to more durable and sustainable improvements in incomes.

Figure 1

There are a number of reasons that high levels of inequality are detrimental to strong, stable, and broad-based economic growth and prosperity. I would like to highlight two of them in particular:

1) Marginal Propensity to Consume

Low- and middle-income consumers spend more out of each dollar they earn as compared to higher-income consumers. That additional consumption is good for the economy—it creates demand that encourages businesses to invest in further production. The economist Alan Krueger once estimated that because of increasing inequality between 1979 and 2007, aggregate consumption was about $480 billion lower every year than it would have been if lower-income consumers had grown more prosperous.

This finding undermines the trickle-down argument that is often used to justify high-income tax cuts. The theory behind this argument is that if wealthy individuals can keep more of their income, they will invest it back into the economy, leading to higher supply and more goods produced. But supply requires a buyer, and if low- and middle-income individuals do not see increases in their earnings, they will not increase consumption. Without greater demand, businesses have little reason to expand production, leaving fewer places for the rich to invest.

2) Human Capital

There is an enormous amount of evidence that inequality prevents people who are low-income or who are discriminated against from building and deploying their human capital and that this is a significant drag on economic growth. Human capital includes all the qualities of a person that make them a more valuable contributor in the workforce. It includes education, training, and hands-on experience.

This is one of the reasons that investing in children, including low-income children, is so powerful and can ultimately also boost incomes and grow the economy. Hilary Hoynes, who is on Equitable Growth’s academic Steering Committee, has found that early childhood programs have huge economic returns. SNAP benefits, for example, have $62 dollars in benefit to society for every dollar of federal money spent, if you account for other positive benefits SNAP has, such as lower infant mortality, increased chance of going to college, and increased earnings.

One of the most frequently cited studies in this literature analyzes U.S. patent holders and finds that when children are exposed to innovation at a young age, they are far more likely to file their own patents in later life. But because disadvantaged youth tend to grow up outside innovative areas and without innovative role models, they patent at rates that are much lower than what school test scores would predict. The research team calls these children “lost Einsteins” and finds that the economic impacts of this loss are high. If children from disadvantaged communities and low-income families invented at the same rate as White men of similar aptitude, we would have four times as many inventors in the economy. Innovation is a key driver of economic growth. This failure to cultivate the talent of people in the U.S. economy and match them to jobs where they can effectively apply their skills is costing the U.S. economy an enormous amount of money. By one estimate, it cost the economy $23 trillion over 30 years.

Yet beyond education and training, human capital also includes the ability to deploy these advantages. A good education is not as useful in the labor market, for example, if a person is not healthy enough to work, has to provide full time care for an elderly parent, cannot afford transportation to get to work, or is being discriminated against. One set of researchers finds that closing the gap in patenting rates between men and women, which is at least partly driven by discrimination, would increase GDP by 2.7 percent. Similarly, Federal Reserve Board member Lisa Cook and her co-author Yanyan Yang find that if more women and African Americans were involved in the initial stages of the innovation process, GDP per capita might rise by between 0.6 percent and 4.4 percent. A different team of researchers finds that expanded opportunity for women and disadvantaged groups accounts for at least 20 percent of growth in per capita output between 1960 and 2010. The empirical economics literature makes it clear that more equitable access to opportunity for all Americans, but especially those who have historically been discriminated against due to gender or race, would yield significant economic benefits.

Public Investments Help Roll Back Inequality and Spur Growth

The good news is that we are now starting to see some real progress to reduce inequality and strengthen the economy. Social supports provided to families during the pandemic contributed to keeping them on firmer financial footing, finding higher-quality jobs, and thereby stabilizing and growing the economy. The economic investments that the federal government is currently making will lay foundations for stronger, broad-based growth for decades to come.

I will discuss public investments in people and public investments in new products and industries in turn, before describing the impact of public investment on the economy.

Investments in People

Increasingly, economists are finding that investments in people can be as important as investments in physical infrastructure, such as roads or bridges. By investments in people, I mean the services and supports that make it possible for people to develop their human capital and participate fully in the labor market. This includes programs that help children and adults develop in-demand skills, care infrastructure that allows people to participate fully in the labor market even while they care for others, and income supports that allow people to maintain the standard of living necessary to be able to search for and maintain good employment.

A large body of empirical research documents the ways that investments in people strengthen the economy. For example, programs such as Head Start, paid leave for new parents, and our federal nutrition programs all provide essential support to babies and young children as they develop the human capital they will need as the workers of tomorrow. These programs keep children safe, healthy, and ready to learn. Research on early care and education programs finds that every dollar in spending generates roughly $8.60 in economic benefits in the long term.

Another important area for investment is the care economy, which not only helps care recipients but also helps others remain in the workforce. The literature suggests that when low-cost child care is widely available to parents, the labor force participation of mothers rises. Similarly, when people can access paid family and medical leave, they are more likely to remain in the workforce while they have a young child or when their spouse experiences a health problem.

Similarly, when people’s living standards are too low—when apartments are not heated, bellies are empty, or medical prescriptions are unfilled—people struggle to obtain high-quality jobs and bring their full productive capacity to work. This is where a crucial piece of our public infrastructure, income supports, comes in. By providing the income people need to maintain an adequate standard of living while they search for work, programs such as Unemployment Insurance help people to match with jobs that best use their skills, benefiting workers, employers, and the broader economy. Early evidence from guaranteed income pilots suggests that when families receive a modest guaranteed income, adults increase their work effort. Moreover, evidence from abroad shows that when low-income workers can meet their economic needs at home, they are more productive at work.

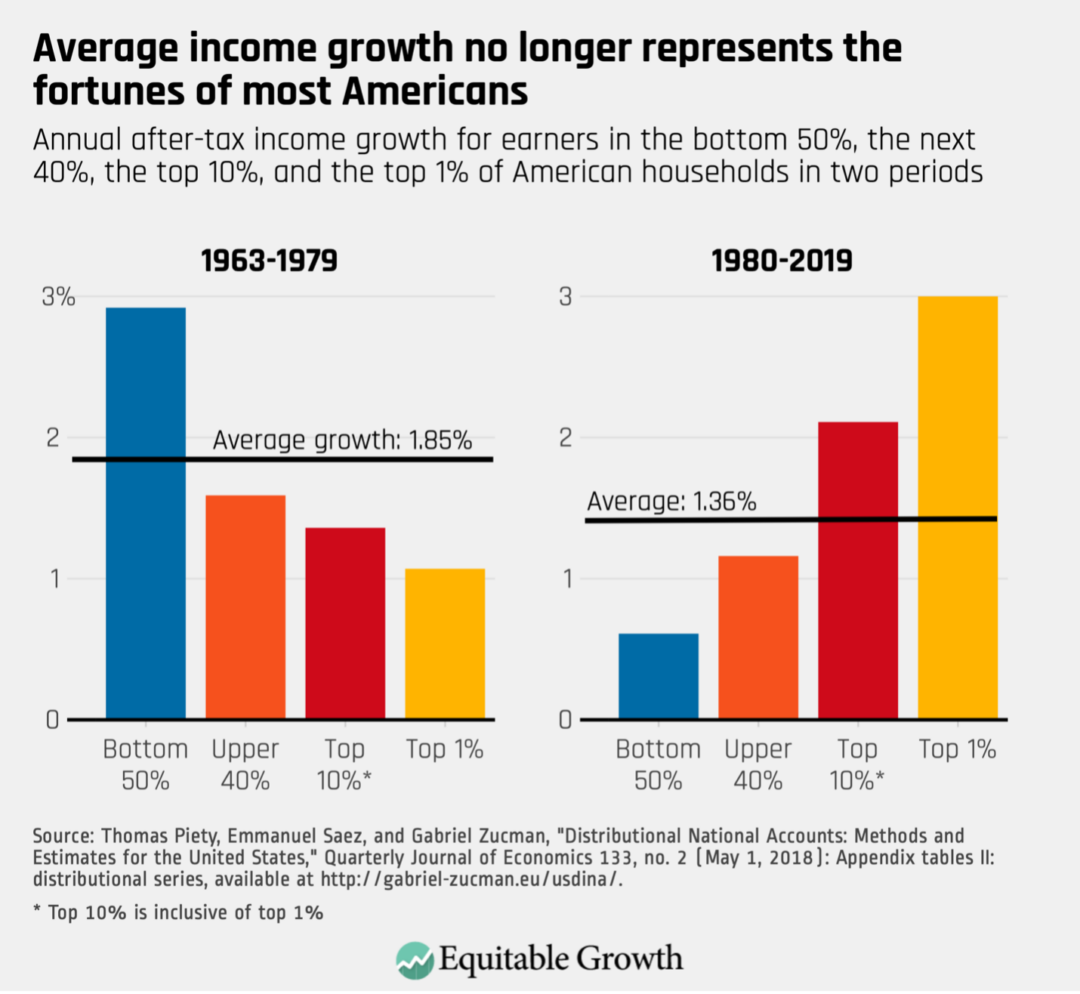

As you would now expect, given the relationship between reducing inequality and growing the economy, sustained government investment in people can create jobs and stabilize the macroeconomy. For example, Rania Antonopoulos and co-authors find that investment in early childhood development and home-based healthcare after the Great Recession could have created 23.5 new jobs per $1 million spent, compared to 11.1 jobs from physical infrastructure investments. (See Figure 2.) Unfortunately, recent Congresses have mostly failed to invest in this area, holding the economy back. To drive down inequality and encourage growth, we have to continue to invest in people.

Figure 2

Investing in New Products and Industries

In addition to passing the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the previous Congress also enacted the CHIPS and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, both of which are large public investments meant to spur equitable growth. Although it is too early to know the full impact of these bills, there is evidence that government-led investment in the products and industries of the future can help ensure the economy meets its full productive potential.

One reason for this is that the basic research and development that ultimately leads to technological breakthroughs is hard for the private sector to monetize. Historically, federal research and development investment, especially in the areas of defense and health science, has helped build technologically advanced industries, such as computer hardware and software, aerospace, and pharmaceuticals. In a study from 2019, Aaron Kesselhim and colleagues examined all new drugs approved in the United States from 2008 to 2017—excluding biologics, or those drugs produced from living organisms as opposed to drugs produced through chemical synthesis—and found that publicly supported research in nonprofit institutions or spin-off companies that had their origins in public-funded research made important late-stage intellectual contributions to at least 1 in 4 of these new drugs. By far the most prominent recent example is Operation Warp Speed, the public-private partnership that delivered millions of life-saving doses of COVID-19 vaccines across the country and world. Congress appropriated $18 billion to the successful effort.

In her book, The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths, University College London economist Mariana Mazzucato highlights the role of government investment at the heart of major technological breakthroughs, noting that Apple and other successful private companies owe much of their value to government-supported research and development. Nearly all the technologies in the iPhone, for example—including GPS navigation, voice recognition, and touchscreen capabilities—were developed through government investments, while Alphabet’s Google search engine algorithm was funded by the National Science Foundation.

Other, non-R&D types of public investment can also be good for equity and growth. It is well understood, for example, that investments in manufacturing played a large role in driving U.S. economic growth in the 20th century. At the moment, investments in semiconductors are especially strategically important. As the pandemic made clear, the private sector alone cannot ensure that supply chains—both for semiconductors and other vital products—are resilient enough to overcome substantial disruptions. The CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 will invest $52.7 billion in U.S.-based semiconductor research, development, manufacturing, and workforce development. Such public investments can also help reduce racial and geographic inequality by funneling public resources to regions and communities that have previously been neglected.

Ultimately, long-term economic growth will be significantly hampered if we do not address the consequences of climate change, which the Office of Management and Budget projects could reduce federal revenues by $2 trillion annually by 2100. But there is ample evidence that the transition to a green economy, if managed correctly, will be good for workers. According to Heidi Garrett-Peltier, for every $1 million invested in renewable energy or energy efficiency, almost three times as many jobs are created than if the same money were invested in fossil fuels. And in a recent paper, E. Mark Curtis of Wake Forest University and Ioana Marinescu of the University of Pennsylvania develop a measure of green jobs—specifically, occupations in the solar and wind energy fields—and find these jobs tend to be in occupations that are about 21 percent higher-paying than the average in other industries—including fossil-fuel extraction—with the pay premium being even greater for green jobs with low educational requirements.

We therefore have reason to expect that the Inflation Reduction Act’s historic investment in green energy will pay long-term dividends in the form of strong, stable, and broadly shared growth. Indeed, according to a recent paper by Costas Arkolakis and Conor Walsh, the IRA is projected to generate around $970 billion of additional GDP as a result of the transition to renewable energy, due largely to cheaper power prices both in the United States and around the world.

Public Investment Has Led to Significant Improvements in the Economy

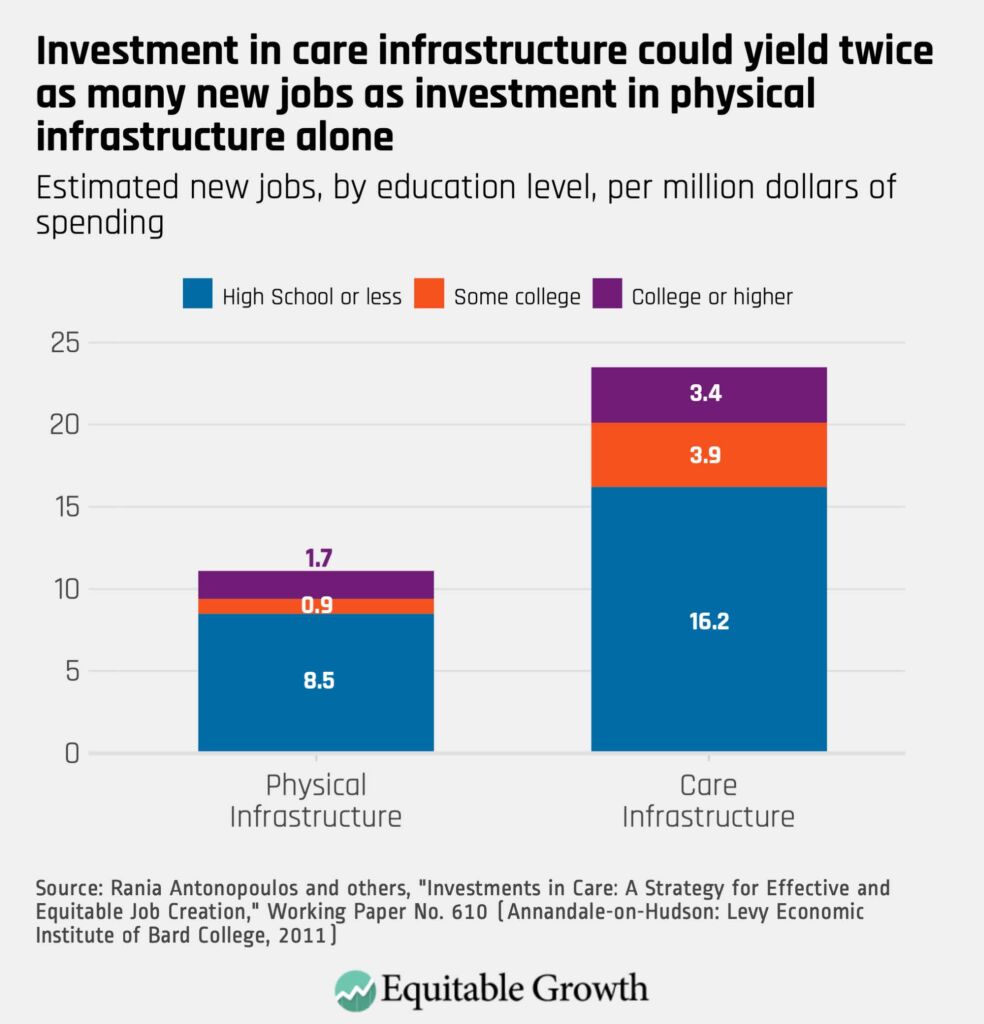

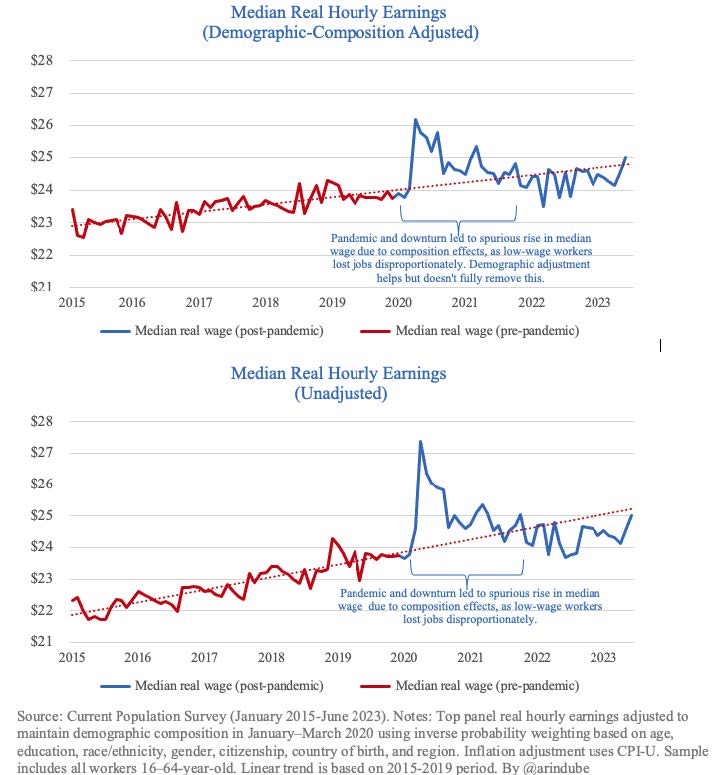

Public investment in the economy is reaping rewards. New metrics published by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis show that between 2019 and 2021, the share of disposable income earned by the bottom half of U.S. households rose nearly 2 full percentage points—the highest level of income for that group since BEA’s first year of data in 2000. And as inequality has come down, the U.S. economy has soared. Employment recovered faster than in any of our previous three recessions, prime-age employment is at a 20-year high, and median real wages, adjusted for inflation and demographic changes, are right back on the upward path they were on in 2019. (See Figures 3 and 4.)

Figure 3

Figure 4

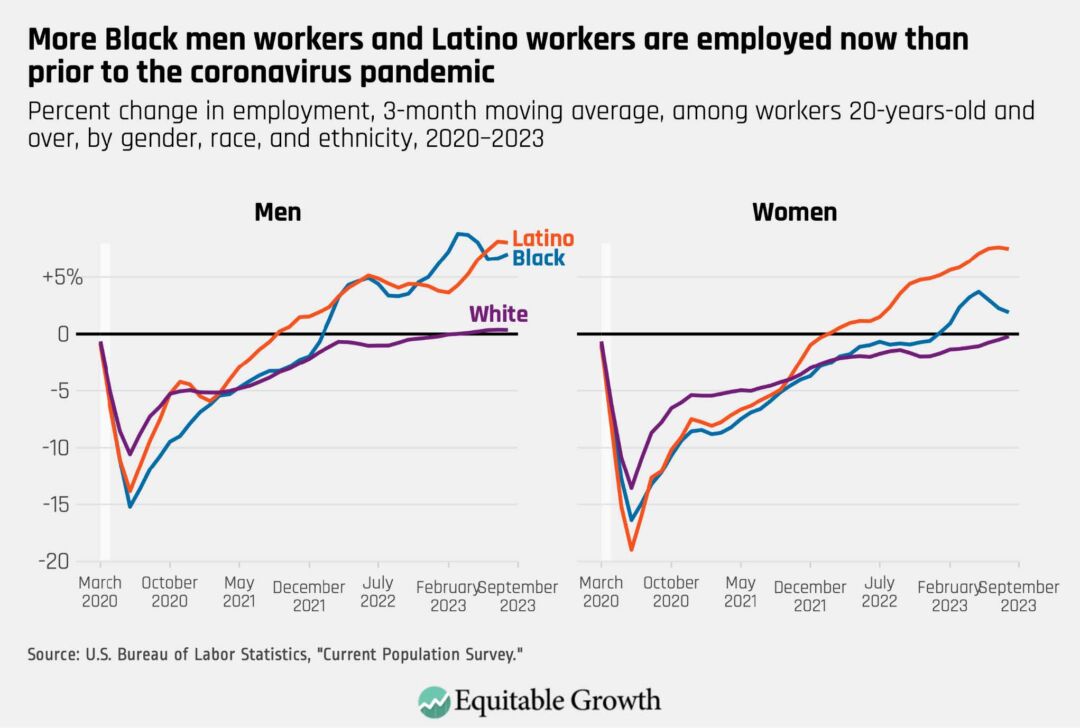

Even groups that have historically been left behind, and were especially hard hit by the pandemic, are benefiting from today’s tight labor market. As of August 2023, Black workers, White male workers, and Latino and Latina workers have surpassed their pre-pandemic employment levels. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

While inflation did spike in 2021 and 2022, price growth has now moderated considerably. Since the beginning of this year, annual PCE inflation fell from about 5 percent to about 3 percent. Over the same period, the economy added more than 1.4 million new jobs, and the unemployment rate stayed roughly flat and is still below 4 percent today. At the same time, wages have risen particularly quickly at the bottom of the income spectrum, helping to compress inequality—a stark contrast with recent business cycles in which the rich quickly recovered while low- and middle-class workers experienced persistent labor market dislocation or “scarring.”

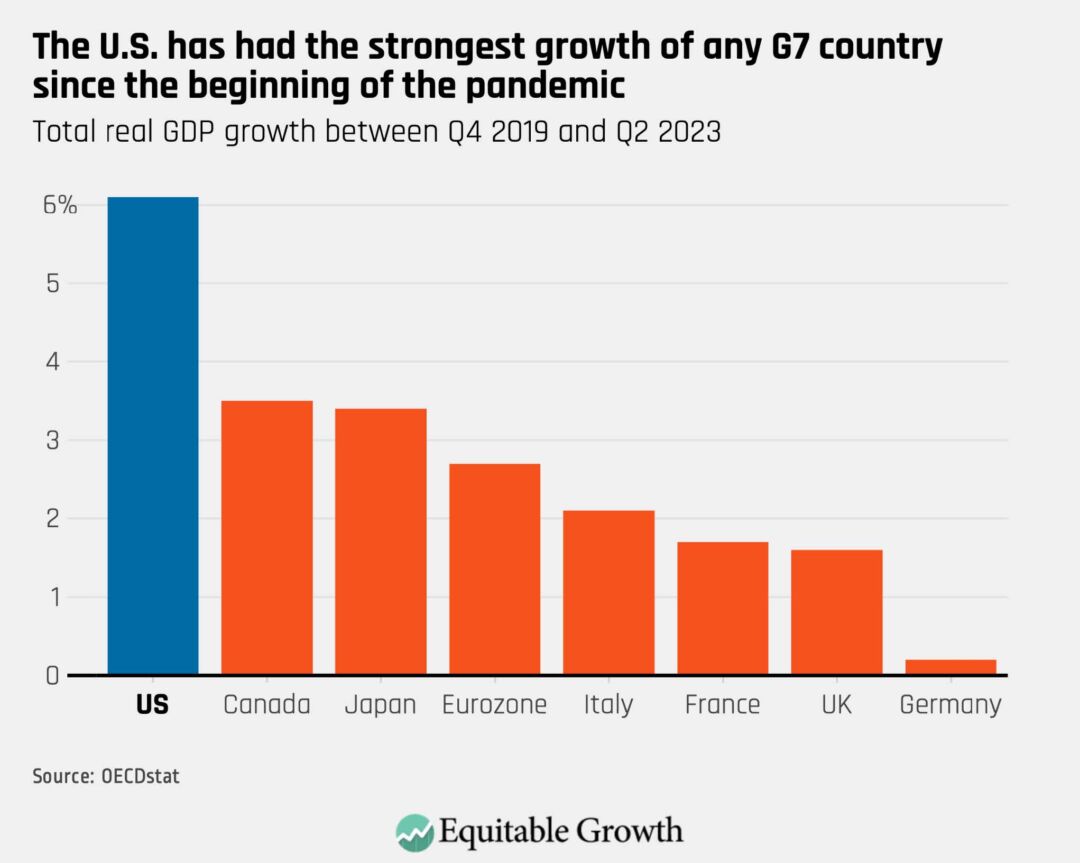

There is now growing evidence that a “soft landing” is within reach. If inflation had primarily been driven by excess demand, bolstered by government spending, economic theory predicts that significant increases in unemployment would have been required to control it. But inflation is now largely declining and the labor market remains tight, which is yet more evidence that the inflation we experienced was not primarily related to excess aggregate demand. Instead, a significant factor in the spike inflation was supply-side shocks sparked by the global pandemic and the war in Ukraine. That is why we saw inflation affect all advanced economics, regardless of their demand side policies. Indeed, the U.S. economy has emerged from the pandemic-induced recession in an enviable global position, with better growth and lower inflation than virtually all of our peers. (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6

I attribute much of this success to the significant investments you and your colleagues made in the American people during and in the aftermath of the pandemic. The expanded Child Tax Credit (CTC), boosted SNAP benefits, and enhanced Unemployment Insurance helped stabilize household finances during the pandemic. Expansion of the CTC, for example, lifted 2.1 million children out of poverty, and last week’s Census Income and Poverty Report showed that child poverty rose sharply after the expiration of the expanded CTC.

These investments were not just good for U.S. families. Economists credit these programs for keeping consumption in the economy afloat during the pandemic. For example, one study found that weekly Unemployment Insurance supplements increased consumption among jobless workers by more than 20 percent, preventing a crash in demand that would have significantly slowed our economy.

Moreover, compare today’s economic recovery to the last one. After the Great Recession, it took about 7 years to get unemployment back to where it had been before the recession began. This time, it took only 2 years, even though unemployment spiked much higher.

Conclusion

As I close, I would like to reiterate my two key takeaway points: First, high levels of economic inequality are detrimental not only to the millions of people left behind economically, but they are also detrimental to strong, stable, and broad based economic growth. Second, the economic policies pursued by the federal government since the start of the pandemic—especially significant public investments and income supports—had a notably positive impact on many of those obstacles to growth and have resulted in strong economic outcomes.

As you consider the 2024 appropriations bills, I would urge you to continue to protect these investments in our economy. Economic inequality in the United States remains elevated, but by investing in people and in our infrastructure, we can achieve strong, stable, and broad-based economic growth that will lift up everyone in the country.