Tariff costs impact industries with mostly White, male, and noncitizen workers

Overview

The U.S. economy is flying blind, with most economic-data publications paused indefinitely due to the shutdown of the federal government amid a general U.S. labor market slowdown and just as the U.S. Supreme Court is due to hear arguments on the legality of the White House’s costly tariff policy. On October 14, new tariffs on imported lumber and furniture took effect, threatening to raise the costs of housing construction at a time when polling overwhelmingly suggests that Americans are deeply concerned about housing access and affordability. And the new furniture tariffs, currently at a baseline of 25 percent, are due to spike as high as 50 percent on January 1, 2026.

Other product-specific tariffs loom. Existing tariffs on automobiles and auto parts, for example, are due to expand to include trucks and truck parts in November. In early October, the White House threatened to slap a 100 percent tariff on pharmaceutical imports from companies that do not negotiate lower drug prices. The Trump administration also floated possible levies on imports of semiconductors, critical minerals, robots, and even movies and iPhones.

In addition to threatening—and, in some cases, imposing—these commodity-specific tariffs, the White House has maintained country-specific or so-called reciprocal tariff rates as high as 50 percent for some countries. The first iteration of Equitable Growth’s tariff tracking project, published in July, focused on these reciprocal tariff rates, finding that they imposed additional input costs as high as 4.5 percent in some industries. Manufacturing, construction, mining, and repair and maintenance were found to be the most impacted sectors by reciprocal tariffs. Since then, some reciprocal tariff rates have changed as trade deals have been negotiated or new levies have been imposed, alongside the new commodity-specific rates.

This second version of this tariff tracking project makes two major contributions to the economic literature. First, it presents updated input cost estimates based on both reciprocal and commodity-specific tariffs. These updated estimates largely corroborate the findings from the July analysis, with manufacturing, construction, mining, and repair and maintenance among the most exposed group of industries to tariffs. Additional input costs are significantly higher in some cases, compared to the July analysis, reaching a peak of more than 12 percent for the primary metal manufacturing sector, which encompasses facilities smelting and refining metals such as steel, aluminum, and copper—metals often purchased from abroad.

Second, this tariff update presents a series of demographic findings about workers in highly exposed industries using worker-level data from the Current Population Survey. Overall, it finds that White and Hispanic men and workers with less than a college education comprise a disproportionate share of employment in the most exposed group of industries. Noncitizen men are also highly concentrated in exposed industries, while younger workers and women of all racial groups are underrepresented.

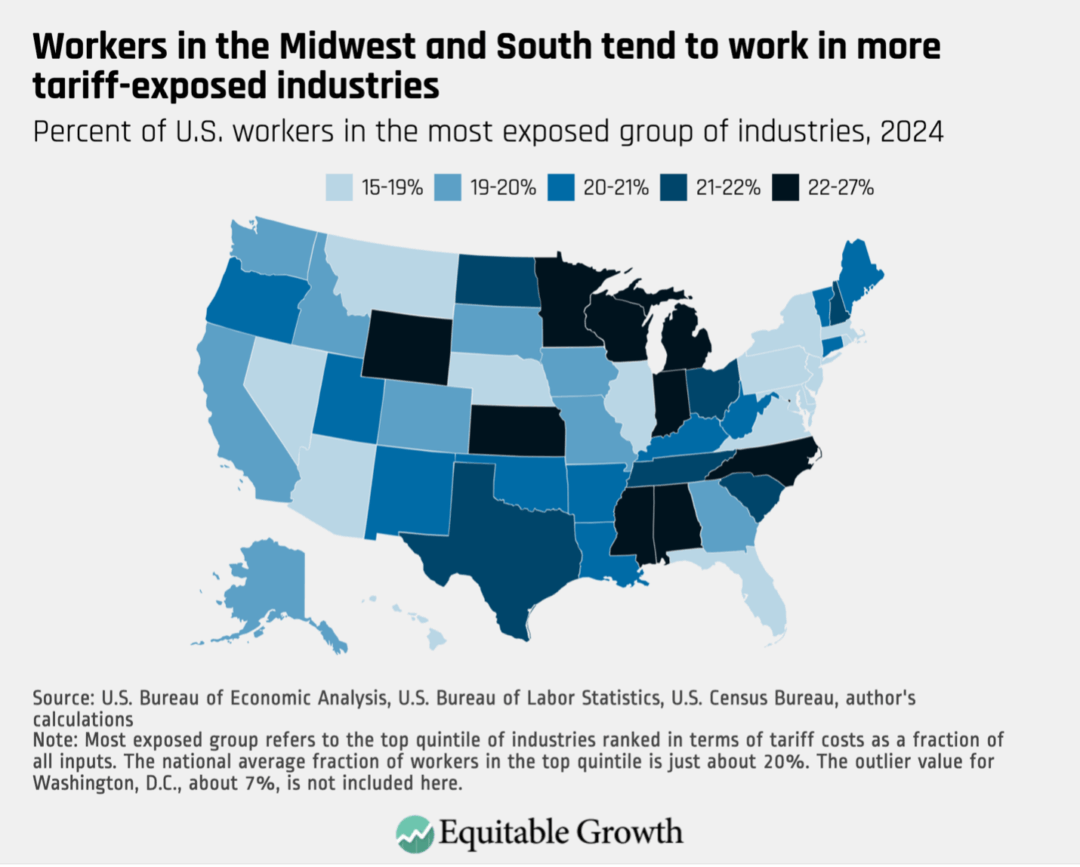

Geographically, workers in the Midwest and South tend toward employment in highly exposed industries, compared to workers in other parts of the country. If businesses pass tariff costs down to workers in the form of slower hiring, slower wage growth, or even loss of incomes or employment, workers in this most-exposed group are likely to be especially impacted.

Let’s first turn to the updated costs of the White House’s current tariff regime.

Rising tariff costs hit U.S. manufacturing industries the hardest

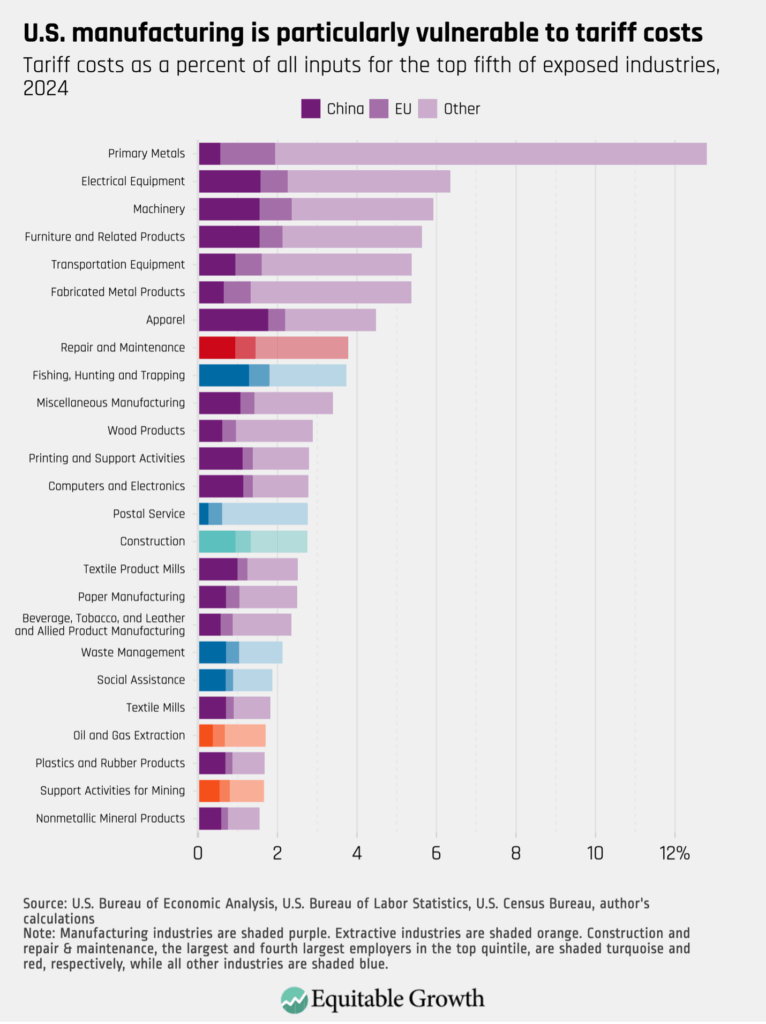

U.S. manufacturers face substantial tariff costs as a fraction of total input costs, with our approximation of commodity-specific tariffs (discussed in the Methodology appendix) weighing especially heavily on the primary metals industry. This conservative approximation means that many manufacturing subsectors reliant on imports of inputs containing aluminum, copper, and steel could face tariff costs closer to the primary metals level of more than 12 percent. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The tariff costs imposed on manufacturing, construction, mining, and repair and maintenance are likely to be passed down to consumers and downstream industries because outputs from these sectors are used as inputs by other domestic industries. In other words, while the immediate costs of commodity-specific tariffs will be borne disproportionately by manufacturing and other select industries, all sectors of the U.S. economy will eventually be forced to grapple with tariff costs as price increases cascade down supply chains.

As discussed in the Methods appendix, this updated tariff analysis includes a handful of industries that appear in the Current Population Survey but were not included in our initial analysis, a few of which show up in the top quintile of exposed industries. These new additions include the fishing, hunting, and trapping sector and the U.S. Postal Service.

The inclusion of the Postal Service in this group is important because more than half a million people worked in the USPS industry in 2024, so tariff-related payroll cost-cutting could have meaningful consequences for the broader U.S. economy. It is also important because similar to manufacturing and construction, the Postal Service is a key logistics industry with significant downstream importance. In other words, tariff costs passed down from USPS firms will have a broad impact on the U.S. economy.

The USPS example is illustrative of another important finding in this tariff update. While tariffs on China, and in some cases the European Union, comprise a significant portion of total industry-level tariff costs, levies on imports from countries besides China contribute most of the additional tariff costs for many of the most exposed industries. This means that while a potential China trade deal could mitigate a significant portion of tariff costs, industries would still face large additional input costs from tariffs on imports from other countries.

This finding is especially important as the White House increasingly turns to commodity-specific tariffs under so-called Section 232 authority of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 while legal challenges to the administration’s authority under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act—under which reciprocal tariffs were implemented—wind through the courts.

Tariffs impact some demographic groups of workers more than others

This iteration of Equitable Growth’s tariff analysis includes worker-level data from the Current Population Survey to better understand the potential demographic incidence of tariff costs, with both economic and political lessons.

While many businesses can accommodate additional tariff costs without cutting their payrolls—by improving operational efficiency, finding alternative input sources, or simply allowing profit margins to shrink—others may be forced to reduce operations, lay off workers, or even close locations altogether. These more extreme consequences are likely to be concentrated in the industries most impacted by tariffs. Comparing workforce demographics in that most-exposed group with broader U.S. workforce averages can help elucidate the potential human consequences of tariff policies.

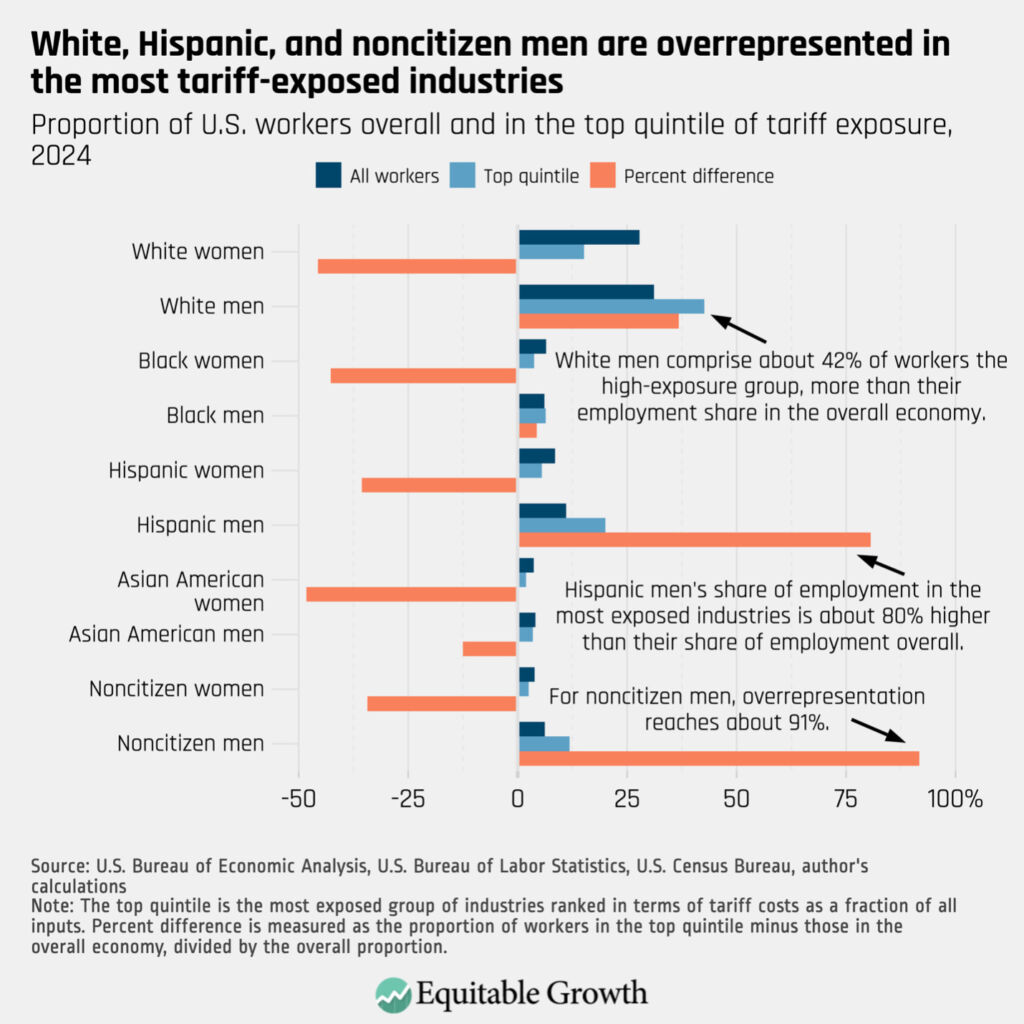

The gender composition of workers is highly lopsided in industries with the highest tariff exposure. While women comprise about 47 percent of the overall U.S. workforce in our sample, they represent only about a quarter of workers in the most-exposed group of industries. This gender disparity is consistent across racial groups, with women always underrepresented compared to men in the most-exposed industries.

The gender disparity is particularly pronounced among White, Hispanic, and noncitizen workers. Hispanic men, for example, comprise a share of the workforce in the high-exposure group that is about 80 percent larger than their share of the overall U.S. workforce. White men’s share of employment in the high-exposure group is about 42 percent larger than their share in the overall U.S. economy. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Union coverage is one of the chief ways workers are shielded from sudden economic shocks such as lost incomes or employment because unions can often push back against layoffs—as federal unions have done during the recent U.S. government shutdown. In our sample, the union coverage rate among the most-exposed industries is about the same as the national average. Yet an analysis of coverage by demographic groups shows some meaningful differences in worker protections.

White workers in the most-exposed group, for example, enjoy a slightly higher union coverage rate compared to the average White worker in the United States. Hispanic and noncitizen workers, meanwhile, suffer a lower union coverage rate in the high-exposure group. This means that workers already at risk of discrimination due to racial and xenophobic bias are comparatively less protected by unions than workers not at risk of discrimination.

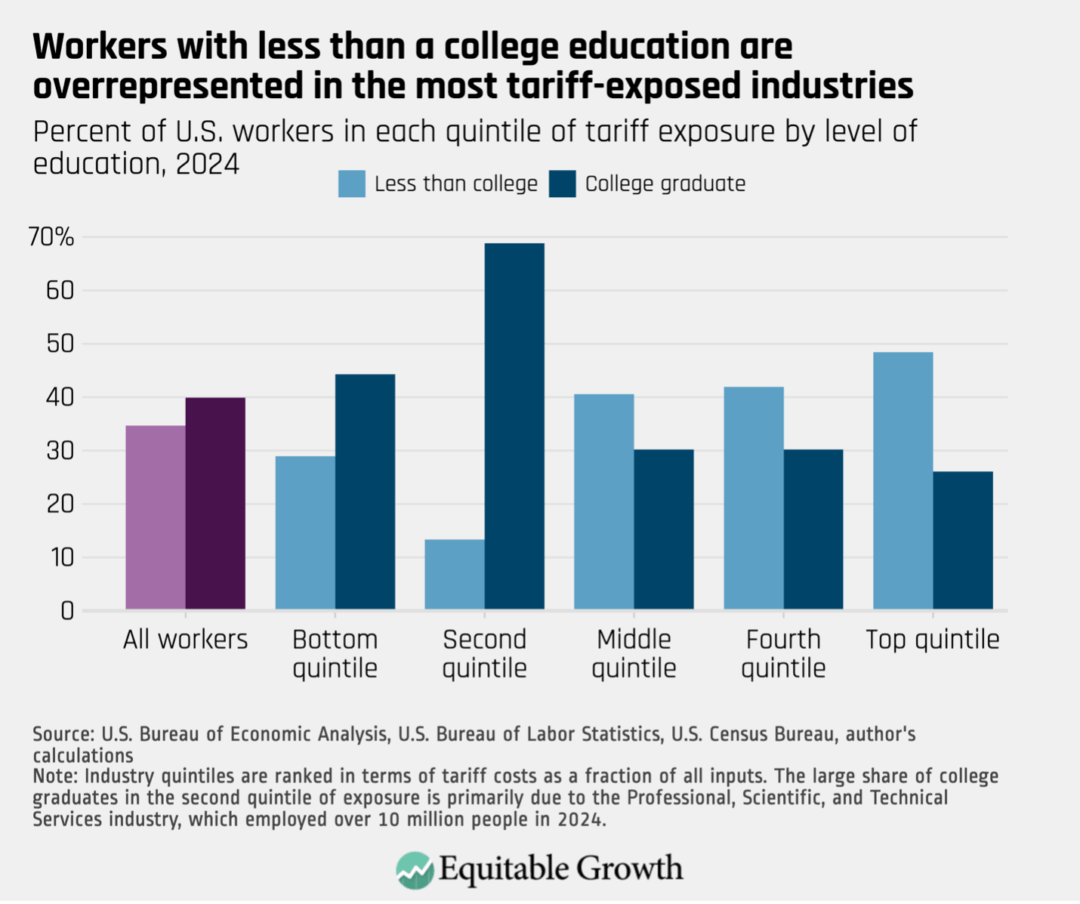

Educational attainment represents another key fault line between workers in exposed industries and those in the rest of the U.S. economy. Roughly 40 percent of workers in the economy have earned a bachelor’s degree or more, while about 35 percent have achieved less than a college degree. Those proportions invert for the most-exposed industries: College-educated workers comprise about 26 percent of most-exposed industries’ workforce while workers with less than a college education represent well higher than 48 percent. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

A similar pattern holds for young workers in the U.S. economy. People under the age of 25 make up more than 13 percent of the total U.S. workforce but a little more than 10 percent of the workforce in the most-exposed industries. People under the age of 35 make up more than 35 percent of the total U.S. workforce but less than 32 percent in the most-exposed industries. Altogether, any loss of incomes or employment related to additional tariff costs are likely to be borne more by workers with less than a college education and those over age 35.

Broader implications

These demographic findings have broader economic and political implications. First, the latest installment in Equitable Growth’s series on job quality in the United States finds disparities in occupational exposure to artificial intelligence across gender, race, education, and income. More specifically, it finds that women, Asian American, college-educated, and high-income workers were all more likely to work in occupations highly exposed to uses of AI.

In other words, some of the demographic groups least exposed to industry-level tariff costs are the very same groups with high occupational exposure to AI. Workers displaced by AI from cognitive-oriented tasks into manual jobs could face constricted opportunities due to tariff pressures on hiring in manufacturing, construction, and other industries with a tendency toward manual labor.

Separately, evidence from the impacts of the China trade shock in the 2000s suggests that job losses among non-college-educated White men in manufacturing and the demographic labor market shift toward younger, college-educated workers are associated with increased political support for far-right candidates. To the extent tariff costs result in loss of incomes or employment, impacted geographical areas of the country could see political shifts on the margin toward right-wing populism.

Like many of the workers impacted by the China trade shock, workers in our Current Population Survey sample tend to live in some of the historically industrial states in the Midwest and in parts of the South. Michigan stands out, where more than 26 percent of workers in our sample are employed in the most exposed quintile of industries. On the other side of the distribution, only about 7 percent of workers in the District of Columbia were employed the most tariff-exposed industries. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

The political implications here are self-evident: Workers are most exposed to the costs of tariffs in some of the key political battleground states that have determined recent presidential and general elections and in other states that are core to a future electoral strategy.

Conclusion

Tariffs—both country- and commodity-specific—are introducing new and sometimes significant input costs for a handful of foundational segments of the U.S. economy, including manufacturing, construction, mining, and repair and maintenance. These industries produce goods and provide services that are utilized across the entire spectrum of the U.S. economy, meaning tariff-related costs could cascade down supply chains to increase prices for a broad swath of businesses, workers, and consumers. The inflationary consequences of tariffs are not the focus of this paper, but insights into directly impacted industries could help researchers and policymakers interested in studying or crafting solutions to tariff-induced inflation.

Tariff costs also could be passed down in part to workers in the form of slower hiring, slower wage growth, and even layoffs or location closures in the worst-case scenarios. These scenarios become more likely if firms face difficulties in passing down tariff costs through price hikes or in otherwise accommodating costs through efficiency gains or profit losses.

Workers in the most-impacted group of U.S. industries skew male, Hispanic, and noncitizen and tend to be older and less educated than the general U.S. population. Income and employment losses among these groups could risk replicating the economic and political consequences of the China trade shock of the 2000s, which impacted similar economic sectors and groups of workers.

As global economic uncertainty continues to rise and firms absorb tariff policy changes and adapt their supply chains, Equitable Growth will continue to monitor how some costs are pushed off not only onto firms downstream of impacted industries but also onto workers in those impacted industries themselves.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!

Stay updated on our latest research