Supermarket chain Kroger’s takeover of rival Albertsons is a test for U.S. antitrust law on pre-closing dividends

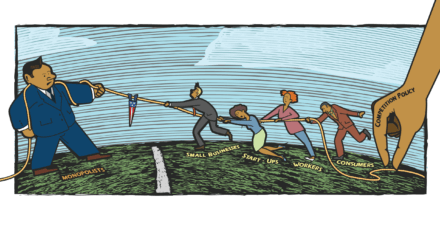

The recently proposed $24.6 billion takeover of the nation’s fourth-largest supermarket chain, Albertsons Companies Inc., by the second-largest chain, Kroger Co., poses an array of serious and apparent antitrust concerns for federal and state antitrust enforcers. There are myriad reasons why state and federal antitrust enforcers could either block the merger or require the two firms to divest some of their grocery stores. The combined firms could raise prices on consumers in an already-inflationary environment and close overlapping stores, leading to employee layoffs, creating “food deserts,” and putting downward pressures on wages and job standards in local labor markets.

But one more immediate aspect of the proposed acquisition is particularly disconcerting—Albertsons’ proposed $4 billion “pre-closing dividend” to its shareholders—because it may well test the boundaries of competition enforcement laws in the United States, particularly the premerger review process. This pre-closing dividend is a novel way in which the shareholders of Albertsons—particularly private equity firms Cerberus Capital Management L.P. and Apollo Global Management Inc., which collectively, with several other private equity firms, hold a majority stake in Albertsons—are seeking to pull money out of the supermarket chain by borrowing more than $1 billion of that $4 billion and raiding the firm’s cash reserves before presumably converting the remainder of their equity to cash when the proposed merger closes.

The use of dividends to enrich private equity shareholders is not new, but the timing of this dividend and its connection with the merger raises novel competition issues. Had the payout of the pre-closing dividend not been blocked by the courts, it would have already been disbursed, long before competition authorities had a chance to decide whether to allow the merger.

The purpose of premerger review is to allow antitrust authorities to block mergers that threaten competition to preserve the status quo. By paying out a crippling dividend before the antitrust authorities have a chance to weigh in on this merger, Albertsons and Kroger would all but guarantee that the status quo would be irrevocably altered, even if the antitrust authorities block the merger.

The threat is not, as some have suggested, that the dividend would open Albertsons to a so-called failing firm defense, which would force authorities to approve the merger. Indeed, the parties appear to have disclaimed any such defense. The threat instead is that the issuance of a pre-closing dividend, no matter whether the authorities approve the merger, would neutralize Albertsons as a competitor.

The proposed pre-closing dividend is being challenged and has been temporarily blocked by a Washington state court. A federal court in Washington, DC, however, declined to do the same. The merger will be the subject of a hearing of the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Competition Policy, Antitrust, and Consumer Rights later this month.

State and federal antitrust enforcers have already signaled they will consider the broader anticompetitive consequences of the takeover for consumers in regional retail supermarket sectors where the two companies’ grocery store chains and brands overlap. But if the Washington state court does not continue its injunction, then the pre-closing dividend itself will likely get paid out to Albertsons’ shareholders before the merger is scrutinized by competition regulators or elected officials.

The pre-closing dividend, if it proceeds, would reward private equity investors who acquired Albertsons in 2006 and then listed the company on the New York Stock Exchange in an $800 million initial public offering in 2020, valuing the company at about $9.3 billon. The mandatory lock-up period for Cerberus Capital Management—Albertsons’ largest shareholder at about 30 percent and the firm which led the initial private equity acquisition of the company for $350 million—and other institutional investors controlling a majority stake in the company expired in September, allowing them to sell the bulk of their shares.

But first, these investors want that special $4 billion pre-closing dividend. Washington state Attorney General Bob Ferguson went directly at this aspect of the proposed merger in his motion before the state court to block the payout. Ferguson asked the court to stay the pre-closing dividend payout until he and other state attorneys general address the anticompetitive concerns with the larger merger. Kroger and Albertsons “have disputed the interrelation between” the merger agreement and the payment of the dividend, and a federal court in Washington, DC last week found the dividend is independent of the merger, even though Albertsons’ own press release announcing the merger described the dividend as “part of the transaction.”

The Washington state court temporarily blocked the payment of the pre-closing dividend on November 3, and late last week, the court extended that temporary injunction until it holds a hearing on November 17. In so ordering, the court noted that once Albertsons distributes the dividend to shareholders, “Albertsons will be in a weakened competitive position relative to Kroger.” By hobbling Albertsons’ ability to compete before authorities have had a chance to review the merger, Albertsons and Kroger will have made antitrust authorities “unable to carry out [their] statutory duty to protect commerce and consumers.”

Whether Washington Attorney General Ferguson prevails in that hearing presents a challenge for him, for all antitrust enforcers, and for the state and federal courts that will eventually hear the broader case against the proposed merger, should it go forward. The reason: Adjudication of pre-closing dividends in antitrust law is thin. Nevertheless, a recent securities law decision on the significance of dividends sheds some light on how courts should treat the use of dividends to thwart effective review of transactions.

A 2022 case before the Delaware Supreme Court (called “novel” by one law firm because of its decision on pre-closing dividends) involved a merger in which compensation to shareholders of the nonsurviving company was paid primarily through a large ($9 billion) dividend, followed by a nominal (31 cents per share) closing payment. By structuring the payment in this way, the companies hoped to “eviscerate[]” the shareholders’ appraisal rights—the rights of company shareholders to demand a judicial proceeding or independent valuation of a firm’s shares with the goal of determining a fair value of the stock price—by limiting their application to the 31-cent closing payment.

The court, in GPP Inc. Stockholders Litigation, ruled, though, that while the dividend was legal, the amount of the dividend must be considered part of the purchase price and is subject to appraisal rights. Notably, the merging parties in GPP, similar to Albertsons and Kroger, had maintained that the dividend and the merger were entirely separate transactions—although it should also be noted that in GPP, the dividend was conditional on the merger, whereas the Albertson-Kroger dividend is not. Delaware is the corporate home of the bulk of large U.S. companies and its Court of Chancery and Supreme Court rulings on corporate matters carry weight around the nation.

Appraisal rights are not at issue in the Albertsons-Kroger merger—or at least not yet. Nevertheless, the Delaware court’s approach to premerger interest payments suggests that where parties attempt to use dividend payments to avoid scrutiny of their merger, courts will look through the form of those payments to preserve the right to merger review. There is no reason this principle would not apply as much, if not more so, to agency antitrust review as to shareholder valuation review. There also is no reason why this principle should not apply to other aspects of financial and transactional engineering common in private equity transactions.

A signature feature of private-equity-controlled companies is heavy debt loads because private equity firms borrow on the back of corporate assets and cash flow to pay themselves regular dividends. Albertsons is no different and finds itself heavily in debt, yet it’s tapping the leveraged loan market for a portion of the pre-closing dividend. The cash part of the dividend is, in effect, a pre-down payment on Kroger’s merger offer, although under the terms of the pre-closing dividend, the cash portion comes from Albertsons’ cash position.

Private equity funds sapping companies of their ability to compete by loading them with debt and looting their assets is nothing new; indeed, it is unfortunately commonplace. And, while problematic in many ways, such practices are typically not an antitrust violation. What makes this maneuver by Kroger and Albertsons novel, and what makes it an apparent violation of the antitrust laws, is that the decision to hobble Albertsons as a competitor through a massive, debt-funded dividend was the result of an agreement between Albertsons and one of its direct competitors. If this is borne out by the facts, then it would be a novel form of gun-jumping.

Kroger and Albertsons claim the two transactions are independent. In support, they cite that the payment of the dividend is not conditioned on the consummation of the merger. This is true, as far as it goes, but it does not go far enough. The merger and the associated agreement between Kroger and Albertsons could still have enabled the dividend, even without express conditioning. The key to understanding why is the $600 million reverse breakup fee included in the larger merger agreement.

If the merger is approved, the agreement to pay this dividend will not matter much—Kroger will pay for it as part of its purchase price, Albertsons will no longer be a competitor, and the companies will become a legal unity, unable to conspire. If the merger is blocked, however, Albertsons will be on the hook for the dividend and the money it borrowed to pay for it, making it that much harder for Albertsons to compete with Kroger and other supermarkets.

Albertsons’ board surely knew this merger would be closely scrutinized, so why would it agree to this dividend, in which the company might be left holding the bag? Because Kroger will pay for at least part of the dividend either way, thanks to the $600 million reverse breakup fee included in the merger agreement.

In this way, this type of pre-merger dividend can be analogized to a pay-for-delay agreement from the pharmaceutical context, which the U.S. Supreme Court held is illegal in its 2012 ruling in Federal Trade Commission v. Actavis Inc. Instead of a branded pharmaceutical company paying a generic company to delay its entry in the market, as in the Activis case, here, the question is whether Kroger is paying Albertsons—by means of the $600 million reverse breakup fee—to shoot its prospects as a competitor in the metaphorical foot. One way or another, then, Kroger will be buying Albertsons’ competitive silence. And either way, competition and consumers will lose.

Whether the merger agreement and the associated breakup fee were part of the Alberstons’ board’s calculus in approving the dividend is a factual question, but it is one that cannot be answered just by looking at whether the pre-closing dividend is expressly conditioned on consummation of the merger. Instead, what matters is whether the board members considered the interplay between the two transactions and whether they would have made the dividend payment even if Kroger were not footing some or all of the bill. The two transactions were voted on in the same board meeting, and hopefully, this week’s evidentiary hearing in Washington state will help illuminate what went on behind those closed doors.

Regardless of the outcome in this transaction, both the courts and Congress should weigh in on pre-closing dividends before this practice becomes another way for private equity firms and their wealthy investors to use this new twist on financial engineering to undermine merger reviews and harm U.S. consumers, workers, and their families, and overall U.S. economic competitiveness in other industries in which private equity firms are major corporate players.