Sleepwalking into depression: The economic response to COVID-19 in the United States

Almost five months into our country’s response to the coronavirus pandemic and ensuing recession, policymakers seem to have lost the urgency that characterized the initial days of dramatic, bipartisan action. In March, four pieces of coronavirus legislation were passed and signed into law. But over the following 2 months, very little in the way of meaningful new policy action occurred. What’s worse, some congressional leaders, squinting at recent data through rose-colored glasses, are ready to declare “mission accomplished,” letting the previous legislation expire and taking no further action.

Are they right? Well, the stock market is now about even for the year. Unemployment declined by 1.4 percentage points in May, and 2.2 percentage points in June. Retail sales increased by 17.7 percent in May, the largest increase ever. And deaths per day from COVID-19, the disease spread by the novel coronavirus, have fallen by half. With the vast majority of stimulus checks delivered and cashed, and with the extra payments for the unemployed set to expire at the end of July, might the U.S. economy be able to muddle along without further support?

The short answer is no—not by a long shot. The few green shoots of improved economic data belie the fact that the health and economic crises are far from over. In fact, we are in danger of sleepwalking into economic depression.

What real-time data are telling us

A careful review of the data reveals gaping wounds caused by the coronavirus pandemic: large declines in market incomes, consumer spending, and employment, all barely propped up by the temporary government stimulus payments. To prevent economic collapse, it is urgent that policymakers take further action. Congress must continue to support unemployed workers’ incomes, send additional stimulus payments to families to keep them financially afloat and increase spending, and give aid to local and state governments so they don’t have to lay off workers.

But, most importantly, policymakers at the state and federal levels must do more to control the spread of the coronavirus, which is now growing at the rate of 70,000 cases a day.

The April Personal Consumption and Income report from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis showed a historic collapse of consumption expenditures, with total spending down 13.6 percent. The decline came despite a record increase in personal income of 10.8 percent, due to the massive inflow of federal stimulus and Unemployment Insurance payments. Without these transfer payments, personal income would have declined 6.3 percent in April and spending would have collapsed even further. For every dollar of stimulus, households increased spending by 25 cents to 35 cents, according to recent estimates, while previous research shows that every dollar of Unemployment Insurance benefits leads to 27 cents of spending.

Thanks in large part to pandemic-related income support, spending recovered somewhat in May, rising 8.2 percent, but it is still down 9.8 percent from the same period in 2019. The most recent official data, the June Retail Sales report, shows that spending on retail goods has largely recovered to its level from last year, while spending on restaurants remain depressed, down 26 percent from its period last year.

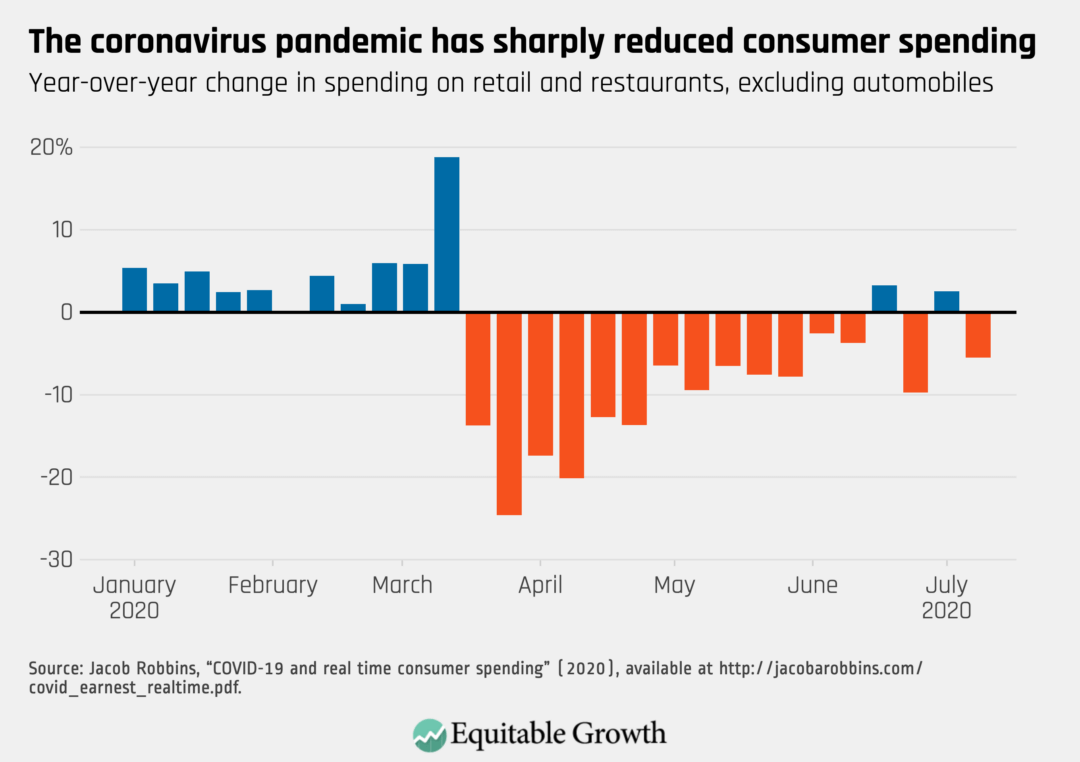

While government data give the most accurate picture of the aggregate economic situation, alternative real-time data are crucially important in understanding the scale of the economic crisis and determining the appropriate government response. In a recent paper, I use real-time payment data from Earnest Research, a company that analyzes spending data from credit and debit cards, to study the latest on how consumer spending is responding to the pandemic.

My analysis based on these data examines measures of real-time retail and restaurant spending growth, comparing weeks in 2020 with the corresponding weeks in 2019. The higher-frequency data show that the spending drop came at the end of March and beginning of April, followed by a partial recovery at the end of April. The revival stalled somewhat in May, but continued again in June, with spending in some weeks actually above 2019 levels. In July, however, there are initial signs that with Covid-19 cases spiking again, spending is declining, with retail spending down 7 percent for the week ending July 15. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Restaurant spending saw a sharper decline and slower recovery: As of July 15, it was still down more than 15 percent. Aggregate service spending saw the largest decline in spending, more than 50 percent, and was still down more than 40 percent as of July 15.

The decline in consumer demand raises the specter that even if businesses are able to reopen after lockdowns end, there will not be enough demand to sustain them. A recent survey of small business owners found their biggest concern is that sales will not be high enough to justify their reopening. Layoffs—initially concentrated in sectors directly affected by the pandemic, such as restaurants and hotels—have metastasized to white-collar sectors, such as professional services, finance, and real estate.

Unemployment remains at a staggering level, with the latest jobs report showing 18 million Americans unemployed. The unemployment rate in June 2020, 11.1 percent, is the highest it’s been since the Great Depression in the 1930s, except for the previous two months. The good news in the report was that this elevated level is down 3.6 percentage points from April, driven mainly by workers who were on temporary layoffs being recalled to their jobs. The largest gains were in the leisure, hospitality, and retail trade sectors. Unemployment among Black workers declined by only 1.3 percent between April and June, about a third of the magnitude of White workers. And the data contained other worrying signs: The number of workers who have permanently lost their jobs increased to almost 3 million.

There are two additional factors that cause the headline number to understate the impact of the pandemic on employment. First, the report counts as employed an extra 2 million people who were “not at work for other reasons” and does not include the 4.6 million who have left the labor force since February. The 2 million were misclassified in error and should rightfully be counted as part of the true unemployment rate. Second, usually workers who leave the labor force are not included in totals of unemployment, but this pandemic presents a special case. Labor force participation fell substantially between February and May; a decline this large suggests that some of the people leaving the labor force may have done so temporarily due to the difficulties of looking for a job. Adjusting for these factors would increase the June unemployment rate to 13 percent.

Another worrying sign in the jobs data is government employment. State government employment declined by 247,00 between March and June, local government employment fell by a staggering 1.2 million, and federal government employment has been flat. As the coronavirus pandemic knocks a massive hole in their budgets, governments are laying off workers by the thousands. Lower consumer spending means lower tax revenue, and new coronavirus-related expenses means higher government spending. As a result, state and local governments are tightening their budgets at the worst possible moment for the economy. These government cuts have disparate impacts on Black Americans, who make up 12 percent of the labor force but 18 percent of government jobs.

The overall picture of the economy, then, is seriously troubling. Consumers are struggling, with incomes propped up by massive government stimulus and unemployment benefits. Some businesses are recalling furloughed workers but are concerned about a lack of demand. And governments are cutting employment and essential services due to unanticipated expenses and rapid declines in revenues. These fundamental issues will not resolve themselves on their own. The government acted with surprising alacrity in passing the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act in March, but further action is needed.

Policy proposals to head off a depression

First and foremost, the extra $600 per week Unemployment Insurance payments, slated to expire on July 31, should be extended and based on automatic triggers tied to an eventual economic recovery. The benefits are not only a lifeline to the 20 million workers who have been laid off but also the thin thread by which consumer spending is hanging. The drop in income and spending from the expiration of this benefit would be catastrophic for an economy in which market income is falling and spending has collapsed. Congress must extend the benefits and not put an expiration date on them, keeping them elevated until triggered off by unemployment returning to normal.

But even this is not enough. Given the collapse in consumer spending, it is clear that more demand support is needed than additional Unemployment Insurance payments. While the $1,200 stimulus payment in the CARES Act was a good start, there is no reason for this to be a one-off benefit. Monthly payments—$1,000 would be a good start—should be made until unemployment returns to normal and/or consumer spending improves.

State and local budget deficits through 2021 might approach $1 trillion. Without additional aid, the shedding of government workers across the country will continue. This is not a short-term issue that can be solved with a one-time stimulus bill. Once again, what is needed is monthly aid to state and local governments that continues until the unemployment rate returns to normal and states’ fiscal health improves.

While each of these policies can help to deal with the symptoms of the economic collapse, the fundamental cause remains the continuing spread of the novel coronavirus and the lethality of COVID-19 uncontained. Many of the layoffs are in the restaurant, travel, and retail sector, whose customers will not come back in sufficient numbers until it is safe to do so. Even with states beginning to reopen, 78 percent of Americans say they would be uncomfortable eating at a restaurant, and 67 percent are not comfortable shopping at a retail clothing store. While the outbreak may have left the front pages of some newspapers, it continues unabated. Around 500 Americans per day are dying from COVID-19, with 70,000 new cases reported each day.

Several of the hardest-hit European countries, such as Italy and Spain, have succeeded in suppressing new cases to the low hundreds per day. They did so by following the only tried-and-true plan that has worked against the coronavirus: a comprehensive program of tracking and tracing, with massive testing and effective tracing and quarantining of those exposed to the virus. Compared with the four economic stimulus plans Congress has already passed, the cost of these public health measures is moderate. Congress has already spent more than $1 trillion on relief and recovery measures—and more will be necessary—but the cost of following the proven path these other nations have taken would run in the relatively modest tens of billions of dollars, and could save additional trillions of dollars in consequently unneeded stimulus costs down the road.

There is much to be done. The federal government, state governments, and local governments must refocus and redouble their efforts to suppress the virus. A plan by Sens. Michael Bennet (D-CO) and Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) would create a national test-and-trace program that would hire hundreds of thousands of people who would help carry out testing, contact tracing, and eventually vaccinating to fight the coronavirus, at the cost of $55 billion. The Medical Supply Transparency and Delivery Act of Sens. Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) and Chris Murphy (D-CT) would finally rationalize the medical supply chain, utilizing the Defense Production Act to ensure the production of critical medical supplies.

At the state and local levels, the burgeoning test-and-trace programs that have been introduced can be scaled up and expanded with increased federal resources. The CARES act allocates some funding for contact tracing, but billions of dollars in additional funding is needed.

Recovery from the coronavirus pandemic and the coronavirus recession is neither close nor assured. This mission has not been accomplished. The federal government needs to act and spend aggressively to support families, workers, and states and localities, and restore consumer demand. Acting swiftly and certainly can mean the difference between a lengthy, weak recovery with unnecessary suffering by those who already suffer from economic and racial inequality, and a strong recovery that leads to stable, broad-based growth and a more equitable economy.