Roads, bridges, bottles, and blocks: Rethinking infrastructure for the post-pandemic U.S. economy

When the COVID-19 pandemic eventually wanes and economic conditions improve, many Americans will be able to safely resume familiar activities that have been curtailed amid the health and economic crises. For many, particularly those who are unemployed, underemployed, or telecommuting, this will mean physically going back to a workplace. But after more than a year of layoffs, school and daycare closures, and new as well as preexisting caregiving responsibilities, many Americans do not have the support they need to return to work.

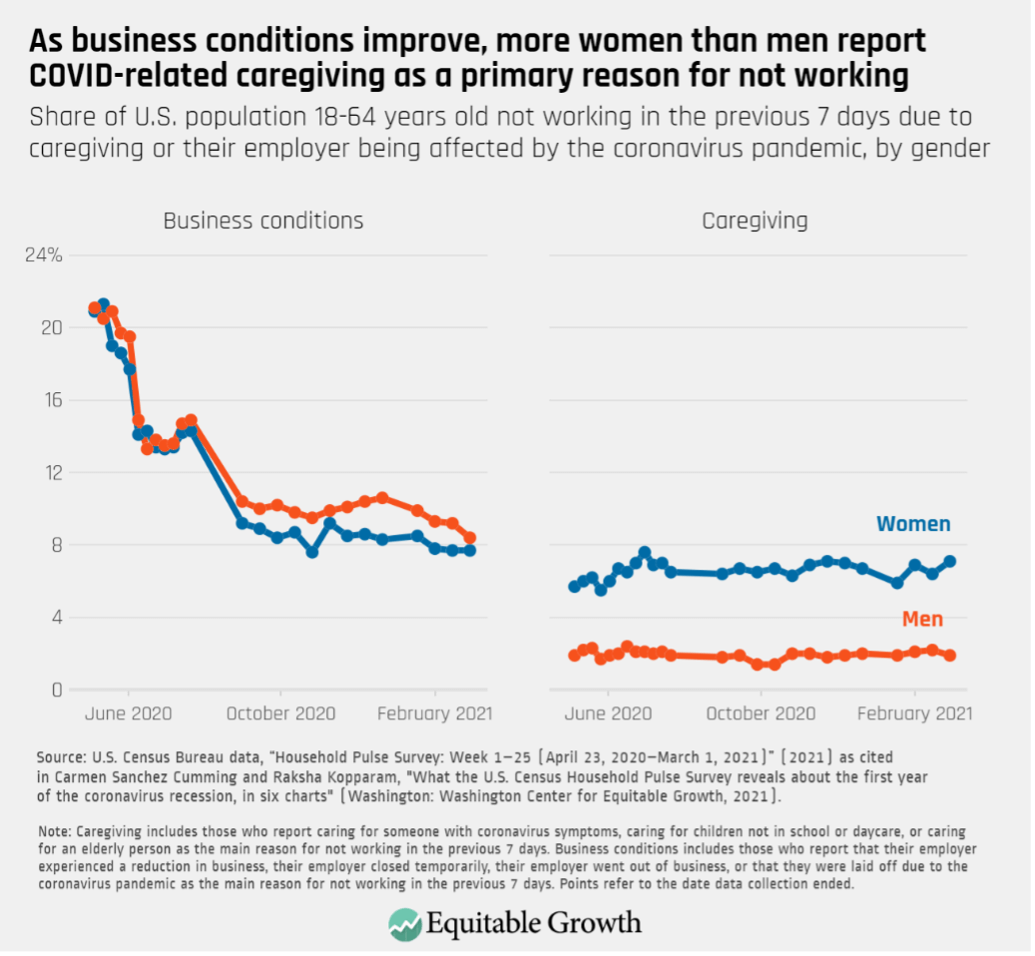

For one thing, not everyone is sharing in the recovery. While the aggregate data may indicate a strengthening economy, women’s labor force participation is at a 33-year low. Job losses among Black and Latina women—who comprise a significant portion of the care workforce—have been particularly stark. Meanwhile, caregiving concerns due to the pandemic continue to disproportionately keep women from work. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Policymakers looking to jumpstart the U.S. economy are expressing renewed interest in the nation’s infrastructure because economic growth and infrastructure are inherently linked. Spending on infrastructure creates good-paying jobs for workers across the wage spectrum. Roads and bridges help employees travel safely to work and allow producers to ship their goods to customers. Electrical grids keep the lights on, and all the various tubes and servers that power the internet keep office workers connected.

To fully recover from the coronavirus pandemic and recession, however, Congress must also address the care economy in any forthcoming infrastructure legislation. Care infrastructure is just as important as physical infrastructure in boosting the U.S. economy and ensuring strong, stable, and broad-based growth. If there is no one to watch children or to care for a sick relative at home while parents are at work, then workers—especially women workers, who take on the majority of home caregiving responsibilities—will remain trapped in the work-life conflict that has come to exemplify the pandemic economy. Without infrastructure that covers the care economy, roads and bridges will remain unbuilt, workers will continue to be stretched too thin, and the recovery from the coronavirus recession will stall.

The American Rescue Plan makes an important down payment on the care infrastructure needed to reduce the spread of the coronavirus and right the economy. Flexible aid to child care providers will help stabilize a precarious market, and the extension of tax credits to cover COVID-related paid leave ensures that this critical public health tool remains accessible to participating businesses.

Even with the passage of this historic legislation, however, there are longstanding structural deficiencies in the nation’s care economy that require a longer-term fix. Fortunately, history and research tell us that investing in our care infrastructure is not only possible, but also has potential for economic benefits that will last for decades to come.

When care was infrastructure: World War II and the Lanham Act

Including “care” as a type of infrastructure may sound unusual to our modern ears, but it was a concept well-understood in the 1940s. Among women whose husbands were in the U.S. armed forces, labor force participation rates shot up from 15.6 percent in 1940 to 52.5 percent in 1944. In preparing the armed forces and production lines to respond to World War II, Congress also mobilized an army of caregivers to support this wartime realignment of the economy. With fathers off at war and mothers off to the factory line, child care became a matter of national importance.

The public response, according to historian William M. Tuttle Jr.’s review of 1940s child care policy, was a mix of moral panic and uncertainty in the country’s ability to meet this need. In response to these concerns, advocates and organizers engaged in practical, grassroots planning to address the child care crisis, including calls for a national nursery school system. In the following years, as Tuttle Jr. describes, the country embarked on a bold public and private expansion of care infrastructure to support mothers involved in the war effort.

In many respects, the child care system that emerged in the 1940s looked like the patchwork system of today. Most mothers relied on informal caregiving from family members, and private care centers opened across the country, often operated by firms engaged in wartime production seeking to attract new female workers. By 1942, the Children’s Bureau (now under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) began issuing local grants for Extended School Services, which used communities’ existing infrastructure to provide afternoon care for school-age children.

But the federal government’s boldest action—and the biggest departure from today’s child care system—was a short-lived experiment with universal, federally funded child care centers. Using funds from the Defense Housing and Community Facilities and Services Act of 1940—popularly known as the Lanham Act—the U.S. government funded care centers in more than 650 communities with defense industries across the country.

It is important to note that the Lanham Act was not designed as a child care bill. It was a public works initiative intended to help localities shore up the housing and infrastructure needs of communities engaged in the national defense. The federal government, however, understood that parents could not productively contribute to the war effort if they did not have someone to care for their children. Policymakers recognized that child care is as important as a roof overhead or a road connecting homes to factories and responded accordingly. Families were eligible to send their children to these Lanham Act centers, regardless of income, for a small fee. Adjusting for inflation, the cost to families was less than $11 per day.

Of course, not every child who needed care had access to a Lanham Act center, and centers were only available for a short time, from 1943 to 1946. When soldiers, sailors, and marines returned home from the war, many reclaimed their old jobs and women were pushed out of the workforce—and the perceived need for universal, accessible child care went with them. This perception would prove untrue in the ensuing decades, which were marked by rising labor force participation among women.

Despite the limitations of the program, however, a 2013 study identified both short- and long-term benefits. Using U.S. census data, Arizona State University researcher Chris Herbst found that communities with access to high levels of Lanham center funding were associated with greater labor force participation for women and improved education and employment outcomes for their children in the decades following the war.

The lessons from the U.S. wartime commitment to the care economy are threefold. First, it is politically and economically possible to develop a care infrastructure that supports capital infrastructure. Second, a solid care infrastructure supports short-term labor force gains and long-term human capital developments. And lastly, letting the care infrastructure fade with the crisis—as policymakers did at the end of World War II—only undoes these gains and ensures families remain trapped in a work-life conflict for decades longer than necessary.

Nearly 50 years after the end of the war, historian Tuttle Jr. closed his review of child care policy in the 1940s with this critique: “The tragedy of the Second World War experience is how little carry-over value it had in the decades since 1945, even in the face of the country’s mounting need for child care.”

Policymakers responding to the COVID-19 pandemic and recession have similarly demonstrated necessary support for the care economy and income-support programs in the midst of the crisis. Whether their support carries over to the post-pandemic economy will have important implications for the speed of the economic recovery, as well as the economic security of workers for years to come.

Building the infrastructure of an equitable post-pandemic U.S. economy

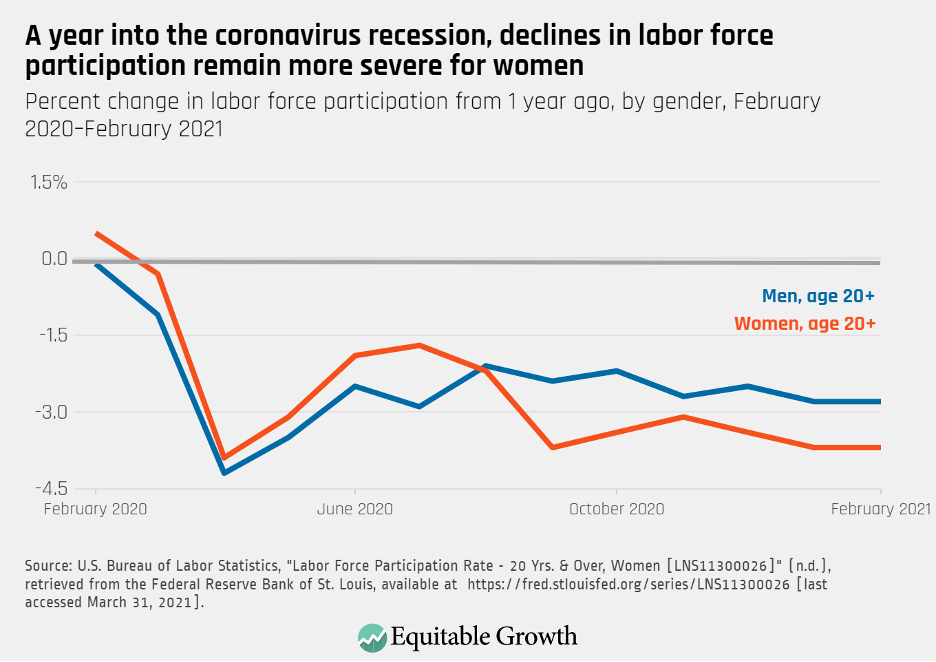

Cracks in the nation’s care infrastructure worsened the economic toll of the coronavirus pandemic and recession, particularly among women. More than 2.3 million women exited the labor force in 2020, and many who remained were less productive and overworked. Even as the economy continues to reopen, women are not rejoining the labor force at the same rate as their male counterparts. Among the civilian workforce, women’s labor force participation in February 2021 remains 3.7 percent below the pre-pandemic rate in February 2020, compared to a 2.8 percent decline for male workers. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Research confirms what many families already know: Caregiving responsibilities are major contributors to women’s exit from the workforce. Though the American Rescue Plan makes a significant step toward improving and modernizing the nation’s care infrastructure, policymakers must do more to facilitate parents’ return to the workforce and to create a permanent network of care supports that help families manage work-life conflicts and prepare the next generation of workers. This means significant and creative investments in the child care marketplace and the long-overdue guarantee of paid family and medical leave for workers with their own health needs or caregiving responsibilities.

Such an investment in our nation’s care economy makes good economic sense. Indeed, investments in care can generate more economic activity and twice as many jobs as investments in physical infrastructure alone. Research shows that accessible and affordable child care can improve parents’ labor force participation. Similarly, the bulk of the research evidence suggests paid family and medical leave has positive effects on labor force participation and workers’ health and economic security. More parents and family members working means higher household incomes, increased consumer spending, and a larger tax base to help pay for these infrastructure investments.

Caregiving plays a significant role in the nation’s economy, as it did during World War II. At its core, the original Lanham Act was an infrastructure bill designed to improve the nation’s internal war-making capacity, but it had far-reaching effects that bolstered the country’s care infrastructure and supported the wartime effort by supporting working parents.

Currently, Congress and the White House are eyeing their own infrastructure package to guide spending for the post-pandemic economy. Infrastructure spending can be a valuable stabilizer for an economy in recession, but it should not be limited to roads and bridges. If child care and paid leave are not readily available when the pandemic subsides, then the U.S. economy could be constrained for years to come.

These policies comprise the infrastructure that supports the human capital powering the rest of our nation’s economic activities. Investing in care infrastructure will provide families and businesses with the tools needed to reduce the spread and impact of the coronavirus and emerge from the current recession to a more healthy, productive, and equitable economy.