The latest research on unions demonstrates that they reduce the spread of COVID-19 for workers and the broader public

Fast facts

- The experience of of workers amid the COVID-19 pandemic shows that U.S. workers need labor unions because neither government regulations nor market forces are sufficient to protect workers.

- The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration has improved workplace safety since its founding in 1971, yet thousands of workers are killed and millions are maimed at work each year in the United States.

- Relying on market forces alone to help address worker safety problems is unlikely to meaningfully improve workplace safety because many U.S. workers find it difficult to quit even when facing poor working conditions.

- U.S. workers also may be deterred from moving themselves and their families to new job opportunities because of important family and community ties in their present location, which in turn can lead to local labor markets that are riddled with market failures, such as unsafe working conditions.

- This report demonstrates that labor unions in one key sector of the care economy—nursing homes—can mitigate these market failures by providing workers with a voice in the workplace and enabling them to bargain collectively with their employers.

- This report details why safe worksites are often won through union-led struggles, not automatically generated by market competition, focusing on nursing homes and the broader U.S. economy.

- The benefits of unionization may be especially large for Black workers, who are often exposed to the most dangerous workplace hazards, in nursing homes and writ large in U.S. workplaces.

- The findings in this report suggest that unionization improves health outcomes for workers and reduces racial health inequalities—dynamics consistent with broader research that links public health and racial equality to stronger economic growth.

Overview

Ros Reggans was overjoyed when she learned that her employer, a Chicago-area nursing home chain, had received more than $12 million in COVID-19 relief funds through the 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act. But when she learned that the nursing home was not planning on using these funds to provide staff with more personal protective equipment, higher wages, and paid sick time, she organized her co-workers to go on strike.

“Our patients were dying, our co-workers were dying, and you’re gonna tell me there’s no support for our work? That didn’t feel right to me,” Reggans said.1 For more than a week, 700 nurses, certified nursing assistants, dietary workers, and other support staff walked picket lines, undeterred by heavy snow and an intransigent boss. Reggans, a Black certified nursing assistant, is also a union steward for the Service Employees International Union. She saw the strike as the best way to advocate for what the staff and patients needed.

Eventually, they went back to work after receiving a modest raise, better access to the needed personal protective equipment, and bonus COVID-19 pay, a sum that allowed workers at the nursing home to stop moonlighting at multiple homes for extra money. They knew that they were at high risk of bringing COVID-19 from nursing home to nursing home and infecting patients in the process, but rent and grocery bills add up quickly on low wages. “That extra money we got wasn’t just for our pockets,” Reggans explained. “It’s pretty simple—the safer we are, the safer they are.”2

The experience of Reggans and her union illustrates broader themes about labor unions and workplace safety that are important for understanding the past and future of public health crises. Workers need labor unions because neither government regulations nor market forces are sufficient to protect workers. Although the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration has improved workplace safety since its founding in 1971, thousands of workers are killed and millions are maimed at work each year in the United States.3

Some economists and policymakers argue that market forces alone can help address worker safety problems. Specifically, they believe that those workers who are unhappy with working conditions can simply quit, thus incentivizing employers to improve workplace safety to retain workers. Relying on market mechanisms alone, however, is unlikely to meaningfully improve workplace safety because many workers find it difficult to quit even when facing poor working conditions.

There are many reasons why this is the case. These include market frictions, such as high unemployment, employers’ monopsony power—some firms’ monopoly-like control of labor market conditons in their industries or local labor markets—fear of losing health insurance tied to employment, and incomplete information about workplace safety hazards. All of these conditions make changing jobs burdensome.4

In addition, workers may be deterred from moving themselves and their families to new job opportunities because of important family and community ties in their present location.5 Under such circumstances, firms no longer need to compete to retain workers, and local labor markets become riddled with market failures, such as unsafe working conditions.

Our research shows that labor unions in one key sector of the care economy—nursing homes—can mitigate these market failures by providing workers with a voice in the workplace and enabling them to bargain collectively with their employers. Viewing workplace safety as a contingent and contested outcome allows us to identify different labor market institutions, such as unions, that contribute to better and safer jobs—not just in nursing homes, but across the U.S. economy as well.

This report details why safe worksites are often won through union-led struggles, not automatically generated by market competition, focusing on nursing homes and the broader U.S. economy. As we demonstrate below, the benefits of unionization may be especially large for Black workers, who are often exposed to the most dangerous workplace hazards, in nursing homes and writ large in U.S. workplaces. Our findings suggest that unionization improves health outcomes for workers and reduces racial health inequalities. These dynamics are consistent with broader research that links public health and racial equality to stronger economic growth.6

Unions and workplace safety

Labor unions in the United States have long helped to improve U.S. workers’ safety and guarantee safe worksites. First, unionized workforces enjoy, on average, more comprehensive health insurance coverage, which can improve the overall health of workers and allow them to see doctors more regularly without worrying as much about out-of-pocket costs.7

Second, unionized workers tend to report workplace safety hazards more frequently to the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration because they have fewer fears of management reprisals for speaking up. Third, collective bargaining agreements frequently restrict excessive hours, mediate the pace of work, and enforce the use of personal protective equipment.

In the best-case scenario, workers can use such agreements to insert occupation-specific safety measures that can become permanent features of company policy. Research on unions in healthcare industries, for example, shows that unions improve workplace safety—and even patient outcomes—by securing safe nurse-to-patient staffing ratios, more paid sick leave, and reducing worker turnover.8 Similarly, new research finds that the presence of a union made it more likely that OSHA investigators would conduct an inspection of an alleged violation.9

The reverse is true, too. Research shows that policies that lead to de-unionization, such as so-called right-to-work legislation that is popular in Southern and Midwestern states, have significantly increased occupational fatalities.10

Why unions made a difference in workplace safety amid the pandemic

The union difference was illuminated by the dangers of the pandemic workplace. COVID-19 is, among many things, an occupational disease because essential workers were disproportionately exposed and died at higher rates. During the first year of the pandemic, researchers find that 68 percent of COVID-induced fatalities among working-age adults were among low-wage workers in retail and service industry jobs.11 A similar study finds that workers in essential industries were roughly twice as likely to die from COVID-19 than were workers in nonessential industries.12

Through strikes, walkouts, and protests, essential workers registered their discontent with the pandemic workplace.13 Yet those complaints rarely translated to lasting changes unless they were backed up by a union. Unions were able to mitigate some of the most hazardous working conditions. During the pandemic, unionized workers across essential industries had greater access to paid sick leave and personal protective equipment, and were tested for COVID-19 more frequently.14

Research also shows that unionized workers may be less likely to work multiple jobs and to live in settings associated with high COVID-19 transmission.15 When COVID-19 first hit New York City in the spring of 2020, labor unions representing hospital workers worked closely with administrators and government agencies to rapidly expand hospital capacity while minimizing risk for workers. Unions helped secure access to necessary PPE supplies and ensured that all workers and volunteers were properly trained before being reassigned to new roles in the areas of greatest need.16

Our own research shows that unions also worked to improve workplace safety in public schools.17 We find that the average teachers union was associated with a 33 percent relative increase in the probability of a school district adopting a mask mandate. Our study focused on Iowa during the fall of 2020 because it was one of only 12 states that left the masking decision up to school districts at that time. Iowa was also an ideal state to study because its right-to-work law generates much higher district-level variation in unionization than is seen in states with more labor-friendly legislative environments.

We find that the leaders in Iowa’s teachers’ unions advocated for mask mandates through local school boards, a strategy that filled the policy vacuum in a state without a sweeping mask mandate. The following school year, when very few governors mandated masks in schools, this same strategy was pursued by teachers’ unions throughout the country.18

Unions reduced the spread of COVID-19

To examine the relationship between unions and COVID-19 outcomes, our recent research focused on nursing homes, the epicenter of the pandemic in the United States. The number of deaths from COVID-19 among nursing home residents and staff are greatly overrepresented in the U.S. pandemic death toll, accounting for one-fifth of all COVID-19 deaths to date. Yet this industry is also a dramatic example of the power of labor to safeguard public health.

First, we studied nursing homes in New York state during the first few months of the pandemic. Even after accounting for potential confounding factors, we find that the presence of a labor union was associated with 30 percent lower COVID-19 mortality rates for nursing home residents.19 We also discovered that unionized nursing homes were more likely to provide workers with N95 respirators.

These safer working conditions were secured by unions negotiating with employers, organizing protests, and raising public awareness about PPE shortages.20 These findings suggest that more PPE translated to differences between life and death among unionized and nonunionized long-term care homes during the early phase of the pandemic, when PPE shortages were more widespread.

We then extended this study to the continental United States, assessing whether the benefits of unionization continued from June 2020 through March 2021, the first full year of the pandemic. We find robust evidence that unions were associated with 10.8 percent lower COVID-19 mortality rates among nursing home residents across the country, as well as 6.8 percent lower COVID-19 infection rates among nursing home staff.21 With more than 75,000 COVID-19 deaths among residents in nonunionized nursing homes during the period of our study, the results suggest that there would have been approximately 8,000 fewer resident deaths in less than 10 months if all nursing home facilities had been unionized.

These findings also suggest that the mechanisms by which unions reduced COVID-19 mortality rates extended well beyond providing personal protective equipment, which increasingly became easier to access over the study period we examined. While data limitations did not allow us to pin down these mechanisms, a variety of other factors may play a role in driving the union effect, including offering paid sick leave, limiting the number of workers employed at multiple facilities, or encouraging vaccination against COVID-19.

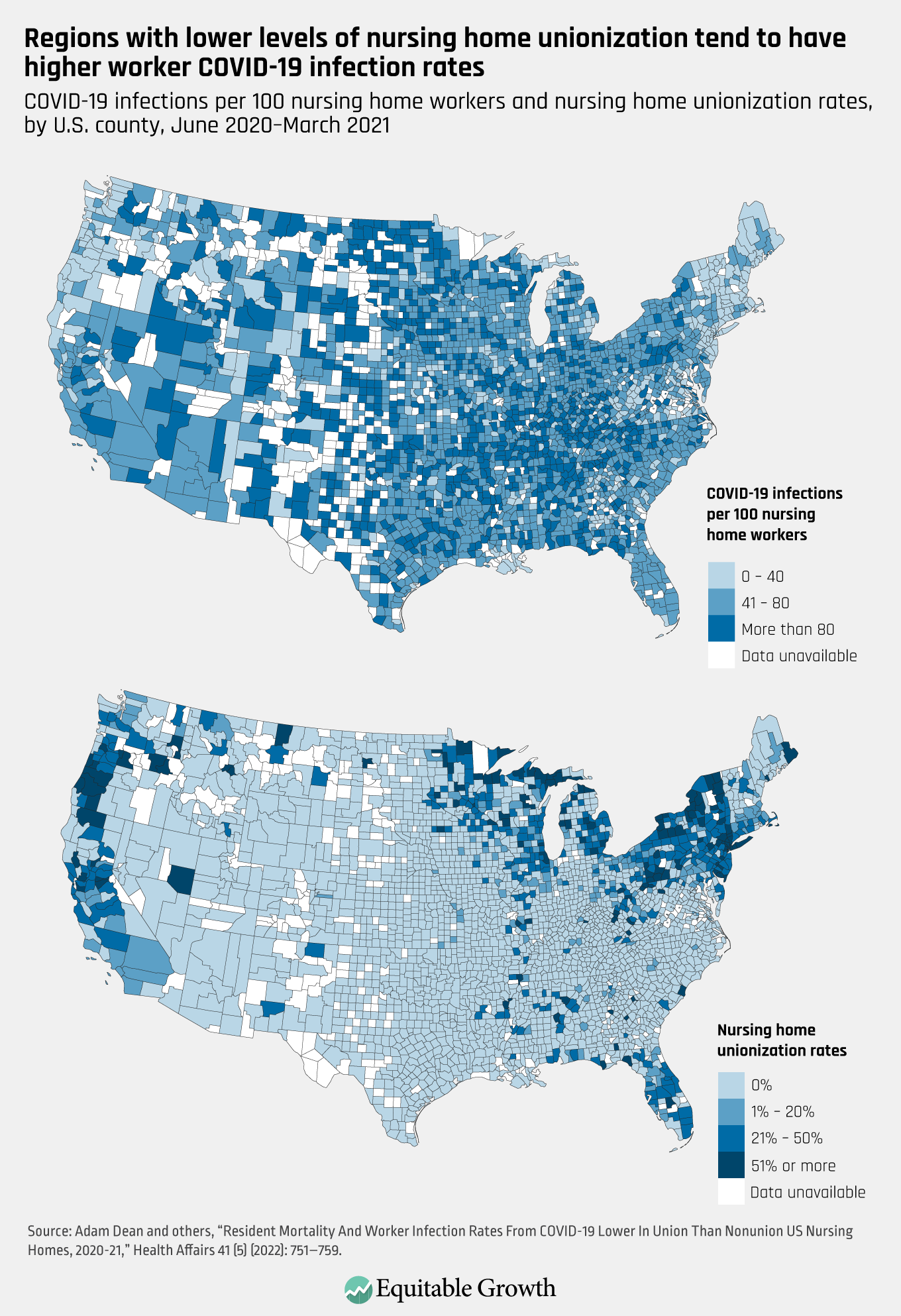

Our regression analysis focused on variation across individual nursing homes and controlled for numerous covariates, but the basic relationship between unions and lower worker COVID-19 infection rates can be seen in the county-level maps displayed in Figure 1. A comparison of these two maps reveals that regions with lower levels of nursing home unionization had higher worker COVID-19 infection rates, just as regions with higher levels of unionization had lower worker infection rates. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Figure 1 shows that the South, for example, had very few unionized nursing homes and high worker COVID-19 infection rates over that period of time. In contrast, the tristate area—made up of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut—had high unionization rates and some of the country’s lowest worker infection rates. Figure 1 also clearly shows the geographical concentration of nursing home unionization rates, with the highest union density rates in a small number of counties in the Northeast, Midwest, and Northwest of the country.

Our research suggests that labor unions improved workplace safety in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Workers in other essential industries have been coming to a similar conclusion and have been requesting union elections at a record pace.22 The recent union victory at an Amazon.com Inc. warehouse in Staten Island, NY, for example, grew out of worker protests demanding that the company do more to reduce the workplace spread of COVID-19.

Similarly, workers at Starbucks retail stores were often motivated to unionize by similar concerns about workplace safety, winning union elections in more than 200 stores nationwide in just the past 6 months.23 And in the gig economy, a 2022 study of ride-hail drivers during the pandemic found that workers with greater exposure to COVID-19 were more likely to express interest in joining a labor union.24

Labor unions provide additional health premiums for Black workers

Our research findings about labor unions and COVID-19 in nursing homes have particularly important implications for racial health equity. First, the nursing home workforce is disproportionately made up of Black and Hispanic women, demographic groups that have faced higher COVID-19 infection and mortality rates throughout the pandemic, as well as greater rates of economic precarity and poor health preceding it.25 Nursing home unions therefore help to protect some of the country’s most vulnerable workers.

Second, the health benefits of unionization may be especially large for Black workers, as discriminatory managerial practices can expose them to the most dangerous workplace tasks.26 And third, even before the pandemic, Black workers were less likely to work in jobs with employer-sponsored health insurance, a trend that was likely exacerbated by job losses in 2020.27 Taken together, these racial disparities help us understand how discrimination and structural racism are entwined with employment in low-wage healthcare occupations.

“Black people are put in harm’s way in nursing homes,” explains Gloria Duquette, a Black Jamaican immigrant who works in three different nursing homes in Bloomfield, CT. “The bosses are White, the supervisors are White, but most of us direct caregivers are Black. Unions have rules in place for fairness, for balance. So, it makes it harder for supervisors to play favors with White workers or discriminate against Black workers.”28

Similar to Duquette’s explanation, scholars have identified numerous ways in which labor unions may help Black workers address workplace discrimination. First, unions educate workers about their employment rights and help them identify illegal racial discrimination.29 Second, unions reduce workers’ fear of retaliation for voicing dissatisfaction with such discrimination.30 Third, many unionized workplaces have formal grievance procedures that enable workers to challenge discriminatory managerial practices.31 Moreover, research shows that unions have the effect of reducing racial resentment among their White co-workers.32

Labor unions secure especially large wage increases for workers of color. Economists Henry Farber and Ilyana Kuziemko at Princeton Universty, Daniel Herbst at the University of Arizona, and Suresh Naidu at Columbia University analyze data from 1936 through 2019 and find that the union wage premium was larger for non-White workers than White workers.33 Similarly, sociologists Jasmine Kerrissey and Nathan Meyers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst examine public-sector wages and find that the benefits of union membership were largest for Black and women workers.34 Shifting focus from wages to wealth, Christian Weller at U-Mass Boston and David Madland at the Center for American Progress find that the union premium is largest for Black union households.35

In short, there are good reasons to believe that the benefits of unionization are especially large for Black workers—which, in turn, helps reduce U.S. wage inequality and boost more equitable economic growth.

While a rich empirical literature demonstrates that the union wage premium is larger for Black workers, few studies examine how the workplace safety benefits of unionization vary across worker demographics. We therefore conducted additional analysis of COVID-19 infection rates among workers in U.S. nursing homes to see whether this union “health premium” was larger in workplaces with higher proportions of Black workers.

To do so, we gathered new data at both the county and nursing home levels. For county-level worker data by race, we use the U.S. Census Bureau’s Quarterly Workforce Indicators, which contains data on the county-level percentage of healthcare workers who are Black. For nursing-home-level worker data by race, we use recently developed estimates based on the characteristics of neighborhoods where nursing home staff reside.36

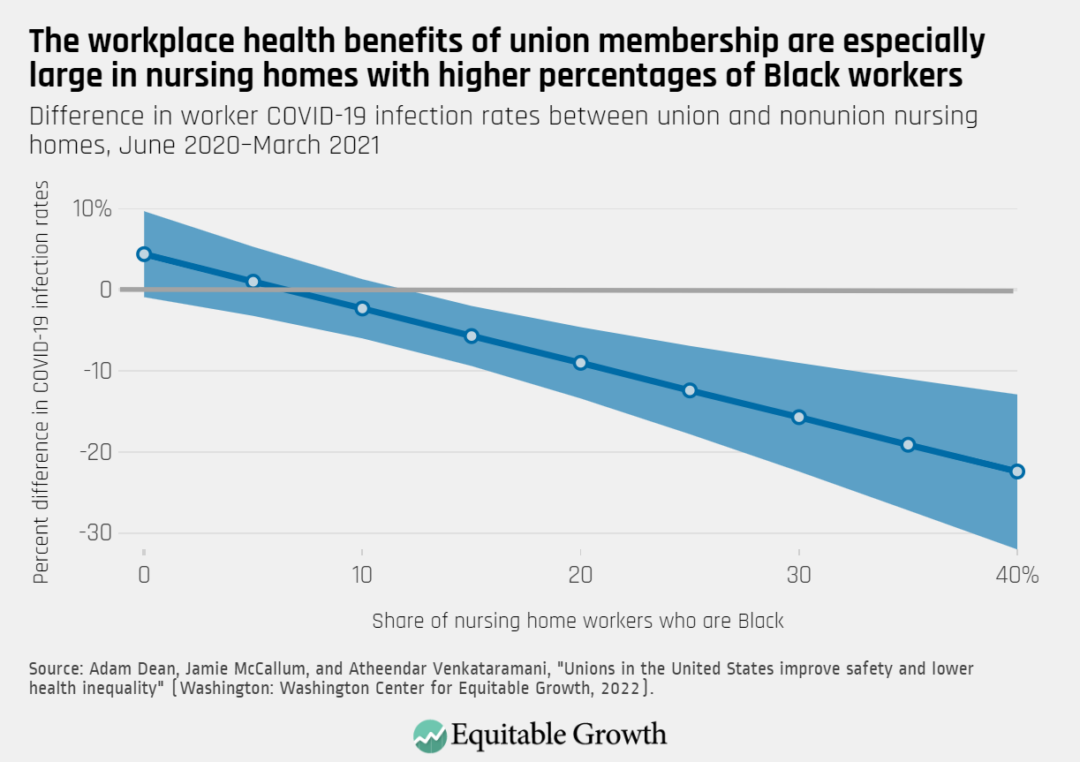

To examine whether and how the union health premium varies across workers’ racial demographics, we built on our recent Health Affairs study of more than 13,000 U.S. nursing homes by assessing heterogeneity in the association between nursing home unions and worker COVID-19 infection rates.37 We find that the union health premium is significantly larger for nursing homes with higher percentages of Black workers.38

More specifically, we find that when the county-level percentage of healthcare workers who are Black is at its mean (15.7 percent), unions are associated with 6 percent lower worker COVID-19 infection rates. When the county-level percentage of workers who are Black is one standard deviation above the mean (29.4 percent), unions are associated with 14.3 percent lower worker COVID-19 infection rates.39(See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Figure 2 demonstrates that the difference in worker COVID-19 infection rates in union and nonunion nursing homes grows more negative as the percentage of Black workers increases. In other words, the workplace health benefits of union membership during the pandemic were especially large in nursing homes with higher percentages of Black workers.40

Conclusion and policy implications

Our research suggests that public health and well-being are linked to workers organizing into unions and thus ensuring higher labor standards. This overarching finding strengthens the case for policies that would bolster the power of U.S. workers to unionize and thereby improve workplace safety. The findings that unions provide especially large health premiums for all workers, but especially Black workers, should inform policy debates about how to alleviate the pandemic’s disproportionate impact on these workers.

Most importantly, our research provides strong evidence for the need to pass the Protecting the Right to Organize, or PRO, Act, which cleared the U.S. House of Representatives in 2021 and now awaits a vote in the U.S. Senate. The legislation would update the Wagner Act, passed almost nine decades ago, and would restore workers’ right to organize without management interference by vastly reducing the obstacles that employers throw in their way.

There are a multitude of reasons to make it easier for workers to form unions. Recent research from the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, for example, demonstrates that if the PRO Act were to facilitate unionization, it would increase workers’ wages and decrease income inequality.41 Our research further bolsters the case for the PRO Act by demonstrating how unions improve workplace safety, highlighting the often-overlooked public health benefits of widespread unionization, especially for workers of color.

U.S. labor history—and the recent upsurges in union activity at corporations such as Amazon and Starbucks—shows that fair labor laws are not an absolute prerequisite for labor organizing. But the pandemic provided the context for a groundswell of interest in unions among the general public and U.S. workers themselves.42 The PRO Act would make it easier for average workers to improve their jobs, a compelling rationale given lax workplace safety enforcement and the failure of labor markets to consistently deliver safe jobs.

While our research demonstrates the power of unions to improve health and safety, workers still need strong policy measures to ensure an adequate level of safety on the job. Less than 10 percent of all U.S. workers are union members, which means that ensuring greater workplace safety requires large-scale policymaking beyond the right to organize. Despite pressure from Congress and a lawsuit by the American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Organizations, the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration refuses to make any permanent protocols specific to occupational exposure to COVID-19 or regulations about airborne infectious diseases. Instead, it issued voluntary guidance with loopholes large enough for the biggest U.S. companies to easily slide through.

In June 2021, the agency finally issued an Emergency Temporary Standard on airborne infectious diseases. But that regulation was hobbled soon after by the U.S. Supreme Court’s subsequent rejection of the OSHA “vaccine or test” mandate at certain workplaces.43 A permanent standard on airborne infectious diseases—akin to the 2000 bloodborne pathogen standard that improved worker safety in the wake of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and the 2014 Ebola outbreak—would create enforceable legal protections for workers in industries that face significant health risks to infectious disease such as COVID-19.

Workplace safety is a crucial component of a healthy and productive economy that generates sustainable and equitable growth. But neither labor market competition nor our current underresourced regulatory framework guarantees safe workplaces. Instead, our research stresses the need for specific policy interventions that can help workers build power from the bottom up. The right to unionize and the right to a safe workplace have been eroded. Public health and safety require that workers win them back.

About the authors

Adam Dean is an assistant professor of political science at George Washington University. His research focuses on international trade and labor politics, as well as the socioeconomic determinants of public health. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago, his M.Sc. from the London School of Economics, and his B.A. from the University of Pennsylvania. His second book, Opening Up By Cracking Down, was published by Cambridge University Press in October 2020.

Jamie McCallum is an associate professor of sociology at Middlebury College. His research focuses on work and labor issues in the United States and the Global South. His third book, Essential: How the Pandemic Transformed the Long Fight for Worker Justice, was published by Basic Books in November 2022.

Atheendar Venkataramani is an assistant professor of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennasylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine and the director of the Opportunity for Health Lab at Perelman. His research focuses on health and socioeconomic inequality—specifically, the effects of economic opportunities on health behaviors and outcomes, the effects of early life interventions on adult health and well-being, and the role of social policies and structural factors in shaping population health. Venkataramani received his Ph.D. in health policy and economics from Yale University in 2009 and his M.D. from Washington University in St. Louis in 2011.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Service Employees International Union for sharing data with us on the union status of U.S. nursing homes.

End Notes

1. Jamie McCallum, Essential: How the Pandemic Transformed the Long Struggle for Worker Justice (New York: Basic Books, forthcoming.)

2. Ibid.

3. David Michaels and Jordan Barab, “The Occupational Safety and Health Administration at 50: Protecting Workers in a Changing Economy,” American Journal of Public Health 110 (5) (2020): 631–635, available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7144438/.

4. Ann Rosenthal, “Death by inequality: How workers’ lack of power harms their health and safety” (Washington: Economic Policy Institute, 2021), available at https://www.epi.org/unequalpower/publications/death-by-inequality-how-workers-lack-of-power-harms-their-health-and-safety/.

5. Rebecca Diamond, “The Determinants and Welfare Implications of US Workers’ Diverging Location Choices by Skill: 1980-2000,” American Economic Review 106 (3) (2016): 479–524.

6. David E. Bloom and others, “Health and economic growth: reconciling the micro and macro evidence.” Working Paper No. w26003 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2019); Dora Costa and Richard H. Steckel, “Long-term trends in health, welfare, and economic growth in the United States.” In Richard H. Steckel and Roderick Floud, eds., Health and welfare during industrialization (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), pp. 47–90; Gopi Shah Goda, and Evan J. Soltas, “The Impacts of Covid-19 Illnesses on Workers.” Working Paper No. 30435 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2022); Robert Lynch, “The economic benefits of equal opportunity in the United States by ending racial, ethnic, and gender disparities” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2022).

7. Thomas C. Buchmueller, John DiNardo, and Robert G. Valletta, “Union effects on health insurance provision and coverage in the United States,” ILR Review 55 (4) (2002): 610–627; Jacob Goldin, Ithai Z. Lurie, and Janet McCubbin, “Health insurance and mortality: Experimental evidence from taxpayer outreach,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 136 (1) (2021): 1–49.

8. Michael Ash and Jean Ann Seago, “The Effect of Registered Nurses’ Unions on Heart-Attack Mortality,” ILR Review 57 (3) (2004): 422–42, available at https://doi.org/10.1177/001979390405700306; Arindrajit Dube, Ethan Kaplan, and Owen Thompson, “Nurse Unions and Patient Outcomes,” ILR Review 69 (4) (2016): 803–33, available at https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793916644251; Linda H. Aiken and others, “Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction,” JAMA 288 (16) (2002): 1987–93, available at https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/195438; J. Spetz, “ Nursing wage premiums in large hospitals: what explains the size-wage effect” AHSR FHSR Annu Meet Abstr 13 (1996): 100–1.

9. Aaron Sojourner and Jooyoung Yang, “Effects of Union Certification on Workplace-Safety Enforcement: Regression-Discontinuity Evidence,” ILR Review 75 (2) (2022): 373–401, available at https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793920953089.

10. Michael Zoorob, “Does ‘Right to Work’ Imperil the Right to Health? The Effect of Labour Unions on Workplace Fatalities,” Occupational and Environmental Medicine 75 (10) (2018): 736–738, available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29898957/.

11. Elizabeth B. Pathak and others, “Joint Effects of Socioeconomic Position, Race/Ethnicity, and Gender on COVID-19 Mortality among Working-Age Adults in the United States,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (9) (2022): 5479, available at https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095479.

12. Chen, Yea-Hung and others, “COVID-19 mortality among working-age Americans in 46 states, by industry and occupation,” medRxiv (2022).

13. McCallum, Essential: How the Pandemic Transformed the Long Fight for Worker Justice.

14. Alexander Hertel-Fernandez and others, “Understanding the COVID-19 Workplace: Evidence from a Survey of Essential Workforce” (New York: Roosevelt Institute, 2020), available at https://rooseveltinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/RI_SurveryofEssentialWorkers_IssueBrief_202006-1.pdf.

15. M. Keith Chen, Judith A. Chevalier, and Elisa F. Long, “Nursing Home Staff Networks and COVID-19,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118 (1) (2020), available at https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2015455118; Hertel-Fernandez and others, “Understanding the COVID-19 Workplace: Evidence from a Survey of Essential Workforce”; Monita Karmakar, Paula M. Lantz, and Renuka Tipirneni, “Association of Social and Demographic Factors with COVID-19 Incidence and Death Rates in the US,” JAMA Network Open 4 (1) (2021): e2036462, available at https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36462.

16. Chris Keeley and others, “Staffing Up For The Surge: Expanding The New York City Public Hospital Workforce During The COVID-19 Pandemic,” Health Affairs 39 (8) (2020): 1426–1430.

17. Adam Dean and others, “Iowa school districts were more likely to adopt COVID-19 mask mandates where teachers were unionized,” Health Affairs 40 (8) (2021):1270–6.

18. Adam Dean and Jamie McCallum, “Strong teachers unions and school mask mandates go together,” The Monkey Cage Blog, The Washington Post, August 20, 2021, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/08/20/strong-teachers-unions-school-mask-mandates-go-together-our-research-finds/.

19. Our regression model adjusts for county-level population and COVID-19 infections per capita. At the nursing home level, we adjust for the average age and acuity of residents, the percentage of residents whose primary support comes from Medicaid or Medicare, whether a nursing home is part of a chain or run for-profit, the percentage of residents who are White, the occupancy rate, and the staff-to-resident ratios for registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and certified nursing assistants.

20. Audrey McNamara, “Nurses across the country protest lack of protective equipment,” CBS News, March 28, 2020, available at https://www.cbsnews.com/news/health-care-workers-protest-lack-of-protective-equipment-2020-03-28/.

21. Our regression model adjusted for the same covariates as the New York study discussed above.

22. National Labor Relations Board Office of Public Affairs, “Correction: First Three Quarters’ Union Election Petitions Up 58%, Exceeding All FY21 Petitions Filed,” Press release, July 15, 2022, available at https://www.nlrb.gov/news-outreach/news-story/correction-first-three-quarters-union-election-petitions-up-58-exceeding.

23. “Current Starbucks Statistics,” available at https://unionelections.org/data/starbucks/ (last accessed September 20, 2022).

24. Michael David Maffie, “The global ‘hot shop’: COVID‐19 as a union organising catalyst,” Industrial Relations Journal (2022), available at https://doi.org/10.1111/irj.12367.

25. David P. Bui and others, “Racial and ethnic disparities among COVID-19 cases in workplace outbreaks by industry sector—Utah, March 6–June 5, 2020,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69 (33) (2020): 1133, available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6933e3.htm; Kathryn E. W. Himmelstein and Atheendar S. Venkataramani, “Economic vulnerability among US female health care workers: potential impact of a $15-per-hour minimum wage,” American Journal of Public Health 109 (2) (2019): 198–205, available at https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304801.

26. Elizabeth A. Deitch and others, “Subtle yet significant: The existence and impact of everyday racial discrimination in the workplace,” Human Relations 56 (11) (2003): 1299–1324, available at https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267035611002; Desta Fekedulegn and others, “Prevalence of workplace discrimination and mistreatment in a national sample of older US workers: The REGARDS cohort study,” SSM-Population Health 8 (2019): 100444, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100444.

27. Marsha Lillie-Blanton and Catherine Hoffman, “The role of health insurance coverage in reducing racial/ethnic disparities in health care,” Health Affairs 24 (2) (2005): 398–408.

28. Interview conducted by Jamie McCallum.

29. Elizabeth Hirsh and Christopher J. Lyons, “Perceiving discrimination on the job: Legal consciousness, workplace context, and the construction of race discrimination,” Law & Society Review 44 (2) (2010): 269–298, available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/40783656.

30. Richard B. Freeman, “Individual mobility and union voice in the labor market,” The American Economic Review 66 (2) (1976): 361–368, available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/1817248.

31. Frank Dobbin, Daniel Schrage, and Alexandra Kalev, “Rage against the iron cage: The varied effects of bureaucratic personnel reforms on diversity,” American Sociological Review 80 (5) (2015): 1014–1044, available at https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122415596416.

32. Paul Frymer and Jacob M. Grumbach, “Labor Unions and White Racial Politics,” American Journal of Political Science 65 (1) (2021): 225–240, available at https://scholar.princeton.edu/sites/default/files/pfrymer/files/ajps12537_rev.pdf.

33. Henry S. Farber and others, “Unions and inequality over the twentieth century: New evidence from survey data,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 136 (3) (2021): 1325–1385, available at https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjab012.

34. Jasmine Kerrissey and Nathan Meyers, “Public-Sector Unions as Equalizing Institutions: Race, Gender, and Earnings,” ILR Review (2021), available at https://doi.org/10.1177/00197939211056914.

35. Christian E. Weller and David Madland, “Unions, Race, Ethnicity, and Wealth: Is There a Union Wealth Premium for People of Color?” Journal of Economics, Race, and Policy 5 (1) (2022): 25–40, available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s41996-020-00078-7.

36. Karen Shen, “Relationship between nursing home COVID-19 outbreaks and staff neighborhood characteristics,” PLOS ONE 17 (4) (2022): e0267377, available at https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.10.20192203. This data is only available for 18 U.S. states.

37. We estimate a cross-sectional negative binomial regression model. Our results are similar when we include additional interaction terms between the percentage of nursing home workers who are Black and each of our nursing-home-level covariates, as well as when we include interactions between unionization and all other covariates.

38. We find that the coefficient for the interaction between the presence of a union and the percentage of workers who are Black is negative and statistically significant.

39. These estimates are based on the county-level QWI measure of worker race. When using our nursing-home-level measure of worker race, which is only available for 18 U.S. states, we find similar results. When the percentage of workers who are Black is at its mean (18.3 percent), unions are associated with 4.4 percent lower worker COVID-19 infection rates. When the percentage of workers who are Black is one standard deviation above the mean (34 percent), unions are associated with 10.5 percent lower worker COVID-19 infection rates.

40. We also find that the union health premium is larger for Hispanic workers than White workers, but the difference is not statistically significant. This null effect may be driven by a lack of statistical power, as the mean and standard deviation for Hispanic workers (5.11 percent and 6.76 percent, respectively) are considerably smaller than those for Black workers (15.77 percent and 13.75 percent, respectively).

41. Kate Bahn and Corey Husak, “The PRO Act addresses income inequality by boosting the organizing power of U.S. workers” (Washington: The Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2020); Farber and others, “Unions and inequality over the twentieth century: New evidence from survey data.”

42. McCallum, Essential: How the Pandemic Transformed the Long Fight for Worker Justice; Maffie, “The global ‘hot shop’: COVID‐19 as a union organising catalyst.”

43. U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, “Occupational Exposure to COVID-19; Emergency Temporary Standard” (Washington: U.S. Department of Labor, 2021), available at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/06/21/2021-12428/occupational-exposure-to-covid-19-emergency-temporary-standard/; Bruce Rolfsen and Robert Iafolla, “Biden’s Shot-or-Test Rule Abandoned After Supreme Court Loss (2),” Bloomberg Law, January 25, 2022, available at https://news.bloomberglaw.com/safety/covid-19-shot-or-test-regulation-to-be-withdrawn-by-bidens-osha.

Related

Explore the Equitable Growth network of experts around the country and get answers to today's most pressing questions!