A first step to making Short-Time Compensation work for the broader U.S. economy

Fast facts

- Part of the wider Unemployment Insurance system, Short-Time Compensation is a social insurance program that helps businesses and workers weather temporary slowdowns in demand.

- While programs akin to Short-Time Compensation are an important component of other high-income countries’ economic policy toolkits, in the United States, Short-Time Compensation is underused: Only 26 U.S states have an operational STC program, and Short-Time Compensation claims rarely make up more than 1 percent of all Unemployment Insurance claims.

- Available data suggest that Short-Time Compensation is especially underused in low-wage service sector industries, such as leisure and hospitality, education and healthcare, and other services—industries that employ a large and growing share of U.S. workers.

- There are a number of reasons why Short-Time Compensation take-up is low, including little information and awareness about the program, interstate variation, and lack of administrative capacity to process and disburse benefits.

- More data and research are needed to ensure Short-Time Compensation fulfills its potential to benefit firms and workers both in the low-wage service sector and across the entire U.S. economy.

- A federal STC program, investments to make the program more user friendly for both employers and workers, and outreach campaigns to ensure firms know about Short-Time Compensation would also go a long way to strengthen the STC system.

- A rigorously evaluated, federally funded pilot of a multistate STC program would allow the U.S. Department of Labor to test these elements of program design at a smaller scale before implementing them broadly.

Overview

Short-Time Compensation—a social insurance program also known as worksharing that is part of the larger Unemployment Insurance system—helps firms weather economic downturns by giving them a way to temporarily cut back on costs without laying off workers. It allows companies to reduce workers’ hours such that their payroll costs are lower and their employees can claim prorated unemployment benefits to replace a share of their lost wages. The workers remain on payroll as part-time employees, though, so that when economic conditions improve, companies can return them to full-time status—thus also removing any difficulty in sourcing and hiring new employees when demand bounces back.

While other countries rely on worksharing-style programs as a major component of their responses to macroeconomic downturns, Short-Time Compensation in the United States is less developed. Many U.S. states lack STC programs altogether, and in the 26 states where the program is operational, few firms actually use it. Further, Short-Time Compensation in the United States is often considered a program best suited to firms that employ workers with specialized skills and that have relatively low turnover rates, such as manufacturers, since these firms have a strong incentive to retain their workforce and thus seem to be a natural fit for Short-Time Compensation.

Yet the goal of increasing STC program access for service-sector employers has emerged recently in policy conversations for two key reasons. First, a large and growing share of U.S. workers are employed in service industries. Second, by many measures, the employment crisis sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic was especially hard on low-wage workers in service-providing industries, such as leisure and hospitality, education and health services, and other services, as well as their employers.1, 2

Indeed, not only were service-sector workers among the most affected in terms of the sheer number of jobs lost,3 but because they are or were employed in what are some of the lowest-paying industries in the U.S. economy, these workers were also particularly likely to experience economic insecurity in the face of unemployment, lost work hours, or illness.4 Making STC more accessible to businesses in low-wage service industries is therefore essential to ensure the program is useful to a big segment of the country’s employers, to workers who are especially vulnerable to negative income shocks, and to the U.S. economy writ-large.

But because Short-Time Compensation in the United States is composed of disjointed state programs that are underutilized overall and rarely used by service-sector employers, it was ill-equipped to serve the needs of a nation experiencing an economic shock that disproportionately affected service-providing industries. To fill the lacuna, the U.S. Congress established the federal Paycheck Protection Program to help businesses across the United States with specific characteristics (including the number of employees) weather the drop in demand and keep workers on payroll. This program faced criticism on its roll-out and reach, and thus sparked a conversation about how the STC program could have been used—and could be used in the future—to better serve employers in the service sector and work to stabilize the U.S. economy as a whole during downturns.

Additionally, as the labor market recovery from the pandemic-induced recession gained steam in 2021 and service-sector employers, along with employers in general, had a more difficult time finding workers to meet increasing demand, some analysts pointed to another way in which a robust STC program could help U.S. businesses weather the ups and downs of the business cycle. With Short-Time Compensation, firms can maintain valuable employment relationships and streamline the costly and complicated process of screening, hiring, and retaining workers.5

Despite its promise, Short-Time Compensation is understudied in the U.S. context. This report outlines key research questions that would advance our understanding of whether and how Short-Time Compensation could be better deployed to support businesses and workers in the service sector, including:

- What are the characteristics of employers and workers who participate in the program?

- How does Short-Time Compensation affect firm-level outcomes, such as profitability and firm survival?

- How does Short-Time Compensation affect worker-level outcomes, such as layoffs, wage scarring, material hardship, and stress?

- How do outcomes vary between employers in the low-wage service sector and in other sectors?

- What program design features would make the program more appealing to employers and more accessible to workers?

With the existing evidence base, however, we can already identify several actions that policymakers can take now to scale the program to be more effective and better able to absorb economic shocks to the service sector. Some of these policy proposals include:

- Establishing a federal STC program, which would allow uniformity across states and raise the program’s profile, so that multistate employers could more easily participate

- Requiring that employers have STC plans on file, which would help employers become familiar with Short-Time Compensation before they are facing decisions about layoffs and ensure that they have a clear plan for when they are determining how to implement Short-Time Compensation at their business

- Waiving experience rating, improving employer experience with program enrollment and administration, and allowing for a greater reduction in work hours, which would make the program more appealing to employers and thereby increase program use

- Implementing user-friendly mechanisms for workers to address issues with their claims, which would ensure that STC systems are accessible to all workers, including service-sector workers and those with second jobs

- Funding and conducting outreach to employers, including service-sector employers, which would complement program design changes to increase program use

A rigorously evaluated, federally funded pilot of a multistate STC program would allow the U.S. Department of Labor to test these elements of program design at a smaller scale before implementing them broadly. It would also answer some of the research questions described above.

Short-Time Compensation keeps businesses afloat, lets workers make ends meet, and helps the economy stay strong and quickly ramp-up again following a slump. By scaling up the program, creating incentives for employers to retain their workforce during temporary dips in business, and bringing Short-Time Compensation into reach for the low-wage service-sector workers who make up such a wide segment of the labor force, the program can reach its full potential.

Introduction

During economic downturns, firms must determine how to weather weak demand and cover their operating costs in the short term without sacrificing their value and production capacity in the long term. Balancing these short- and long-term costs when making these types of decisions is not an easy task, and employers often face tough choices. Should they close down an entire restaurant location or stop serving breakfast across locations? Should they lay off all recently hired staff or pursue targeted layoffs? In many cases, it is unclear which decisions best position the firm—and the workers it employs—to recover from an economic slump. Yet the consequences of these decisions can send ripples throughout the entire economy.

Not all choices need to be so tough. A simple and effective way to support businesses and workers through recessions—and, in turn, create the conditions for a faster and more equitable recovery—is to help them avoid laying off workers, while at the same time lowering their day-to-day costs.6 In the United States, the main way government helps businesses to retain their workforce is through Short-Time Compensation, a social insurance program administered as part of the larger Unemployment Insurance system.

STC programs provide partial wage replacement to workers whose hours are reduced, allowing firms to both retain workers as part-time employees and also temporarily scale back on payroll costs. As such, when the economy recovers, firms can avoid the challenges of rehiring to satisfy demand: Instead of having to go through the recruitment process, they can simply bring their part-time employees back to full-time status. If economic circumstances require them to lay off some workers completely, when demand begins to recover, employers also have the option of recalling laid-off workers at part-time status using the STC program.

Though Short-Time Compensation is touted as a panacea by some, others argue that the program is ill-equipped to meet the needs of today’s U.S. workforce. Employers, after all, can and do reduce the hours of their workforces without participating in a government program. In a labor market in which it is easy and cheap for businesses to dismiss workers, employers may not see the value in seeking government assistance to keep their current workforce on payroll.7

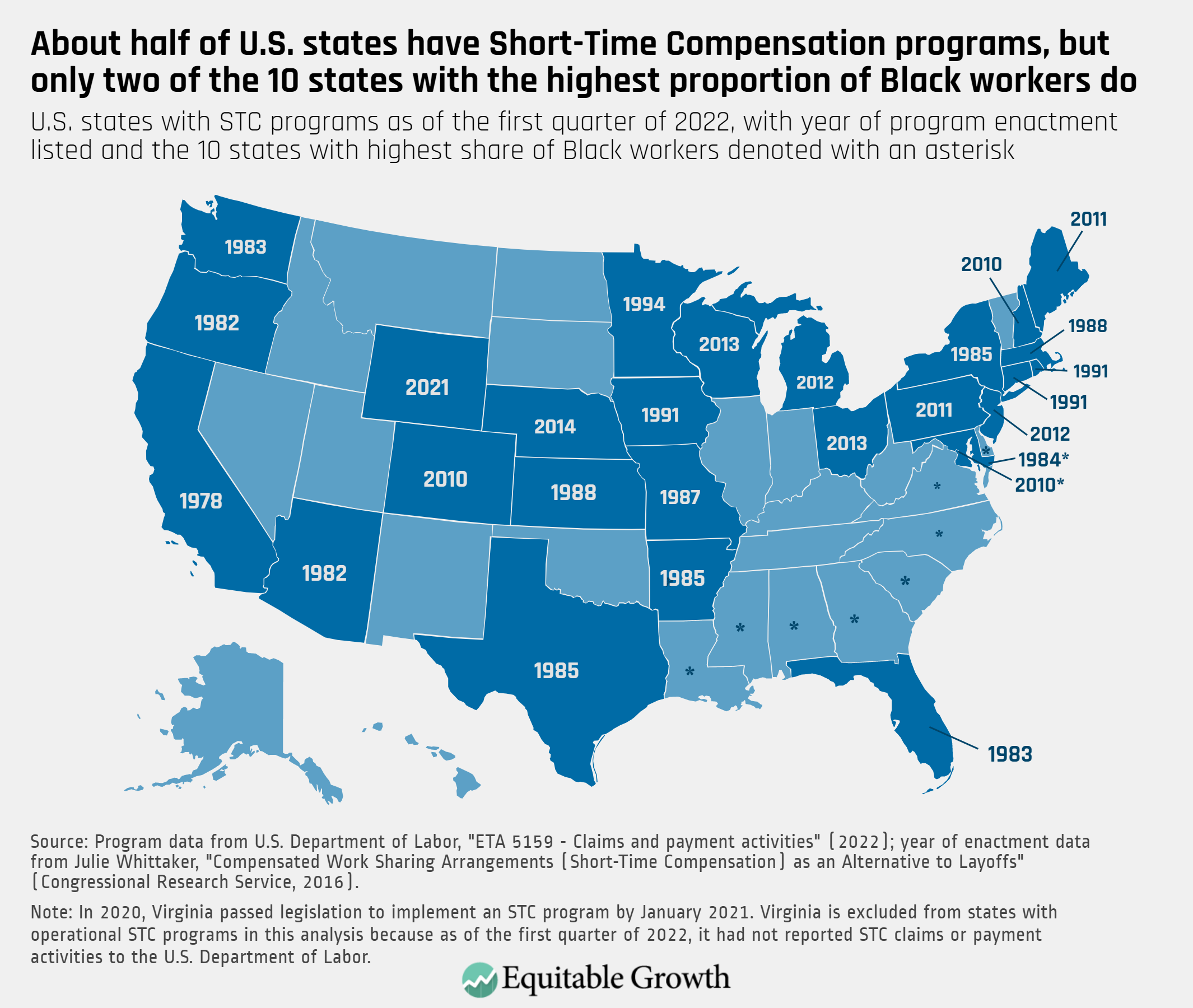

And, in contrast to our European counterparts, whose worksharing systems are well-developed, the U.S. STC system is underused generally,8 is used little outside of the manufacturing sector, and, as it is implemented and run at the state level, is a complex, piecemeal system: In fact, as of early 2022, only 26 states and Washington, DC had operational STC programs in place.9

Critics also argue that Short-Time Compensation is not a good match for the low-wage service sector, which includes industries such as food services, accommodation, and retail—industries in which firms’ business models account for the high rates of turnover that STC is designed to prevent.10 These critics often argue that goods-producing industries, such as manufacturing, construction, and mining, are better-suited to using STC programs.

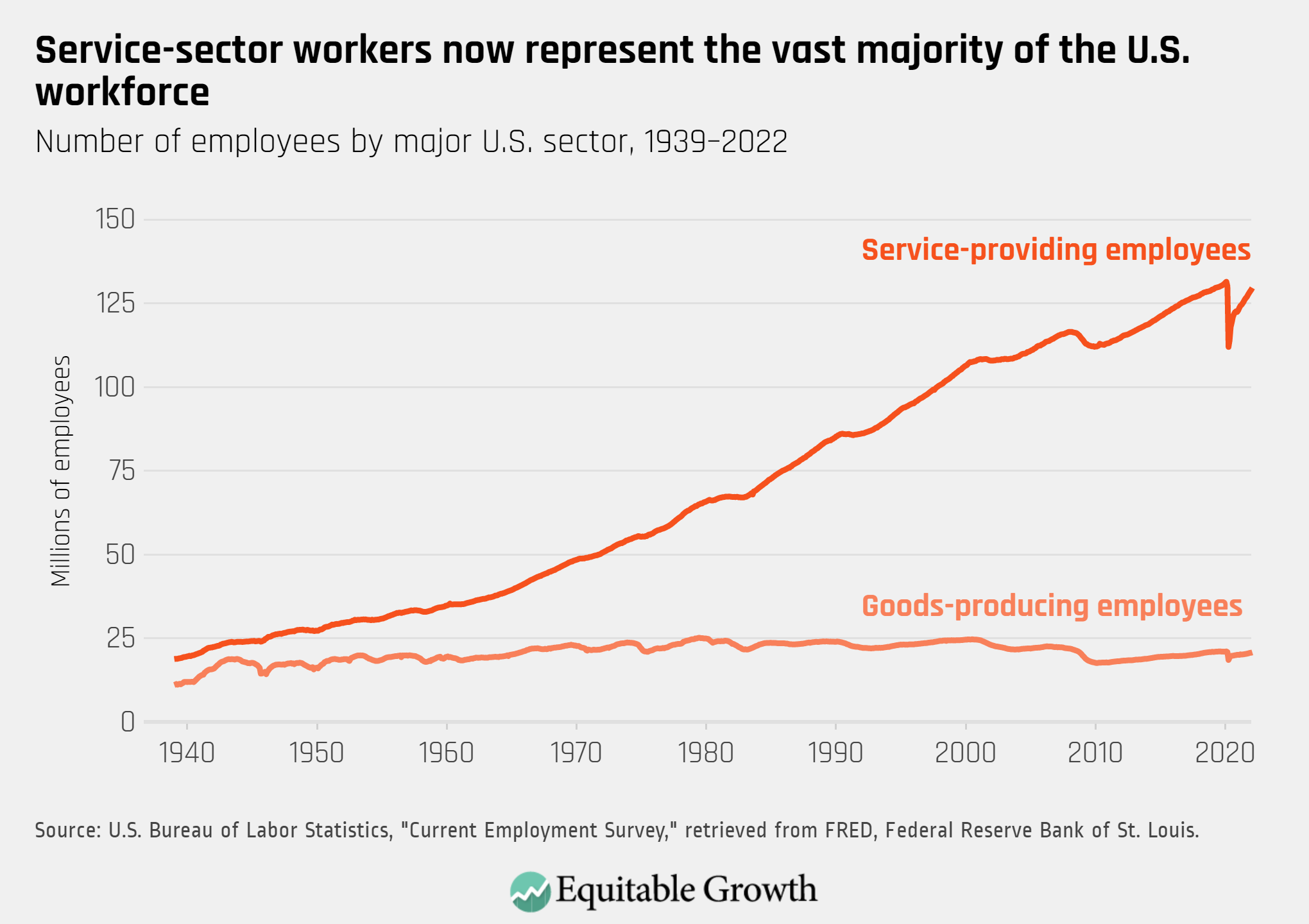

States first began implementing STC programs in the late 1970s,11 when goods-producing industries made up a larger portion of the overall U.S. workforce.12 Since then, however, goods-producing workers have gone from making up 28 percent to approximately 14 percent of the nonfarm workforce in the United States, while service-providing workers have gone from representing about 72 percent of all nonfarm workers in 1979 to representing more than 85 percent in 2019.13 (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

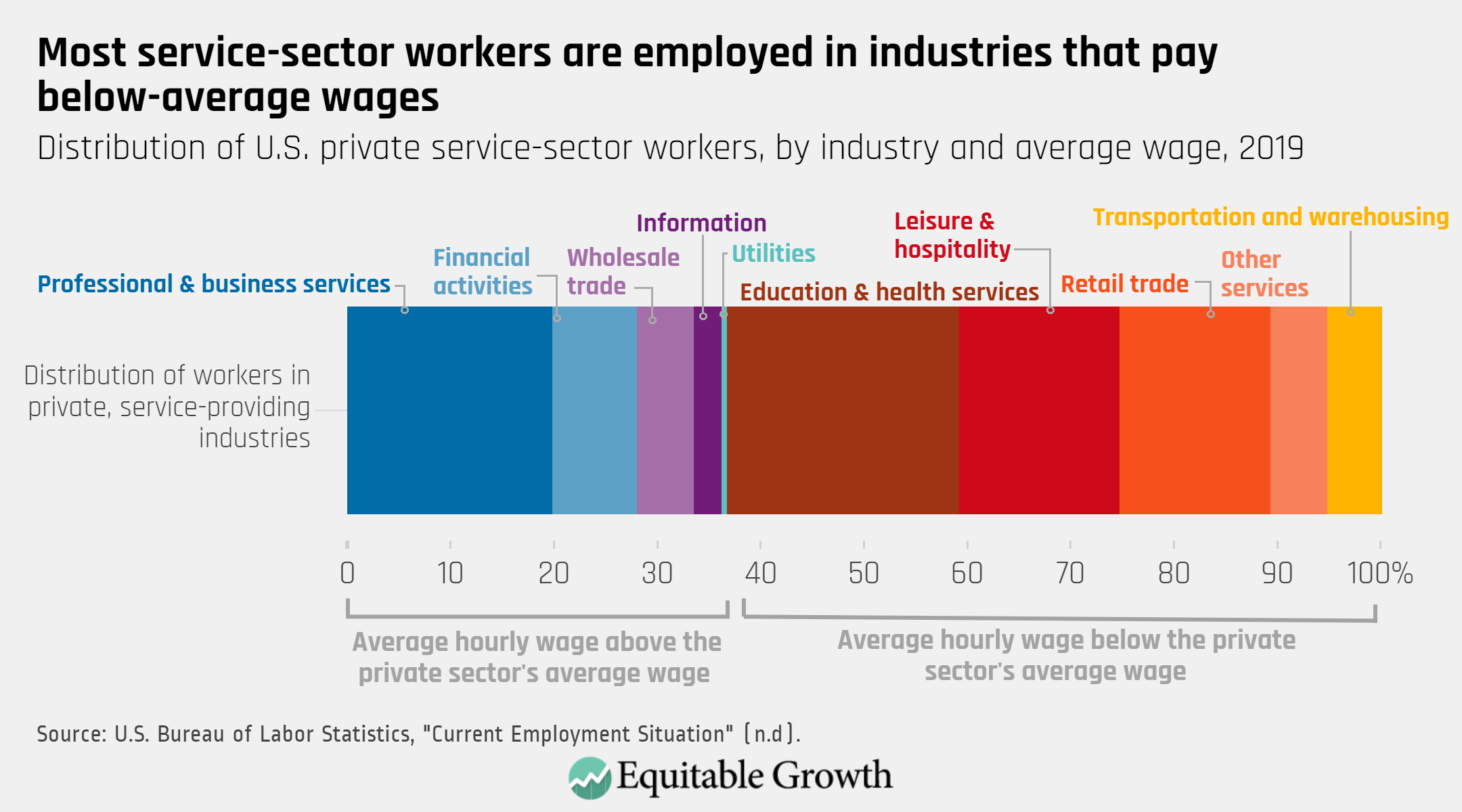

The service sector is composed of a wide range of industries: Both stockbrokers and hotel housekeepers work in the service sector. More than 60 percent of private service-sector workers, however, labor in industries in which the average wage is below the average wage of the private sector as a whole.14 We call this group of industries “the low-wage service sector.” (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

In this report, we explore the potential advantages of expanding STC programs to reach employers and workers in the low-wage service sector, and what it might take to get there. We begin by explaining what Short-Time Compensation is. We then describe the benefits it has for the economy broadly, as well as the benefits it could bring to the service sector specifically. Next, we explore the forces keeping the STC program small in the United States, as well as other challenges that limit its potential as a tool to stabilize the economy during downturns. We then lay out a blueprint for overcoming these challenges, including expanding and streamlining the program and making sure it is better understood by workers and employers alike, especially in the service sector. We close the report with some concluding thoughts.

The time is ripe to explore whether Short-Time Compensation could effectively reach employers and workers in the low-wage service sector. By ensuring that Short-Time Compensation is used more and can be accessed by a much larger share of workers and businesses—including those in low-wage service-sector industries, which disproportionately employ workers of color and low-wage workers in the retail, leisure and hospitality, and healthcare industries—it would be easier for firms to navigate short-term slumps in demand, strengthen workers’ job security and income stability, and build a more resilient U.S. economy.

What is Short-Time Compensation, and how is it financed?

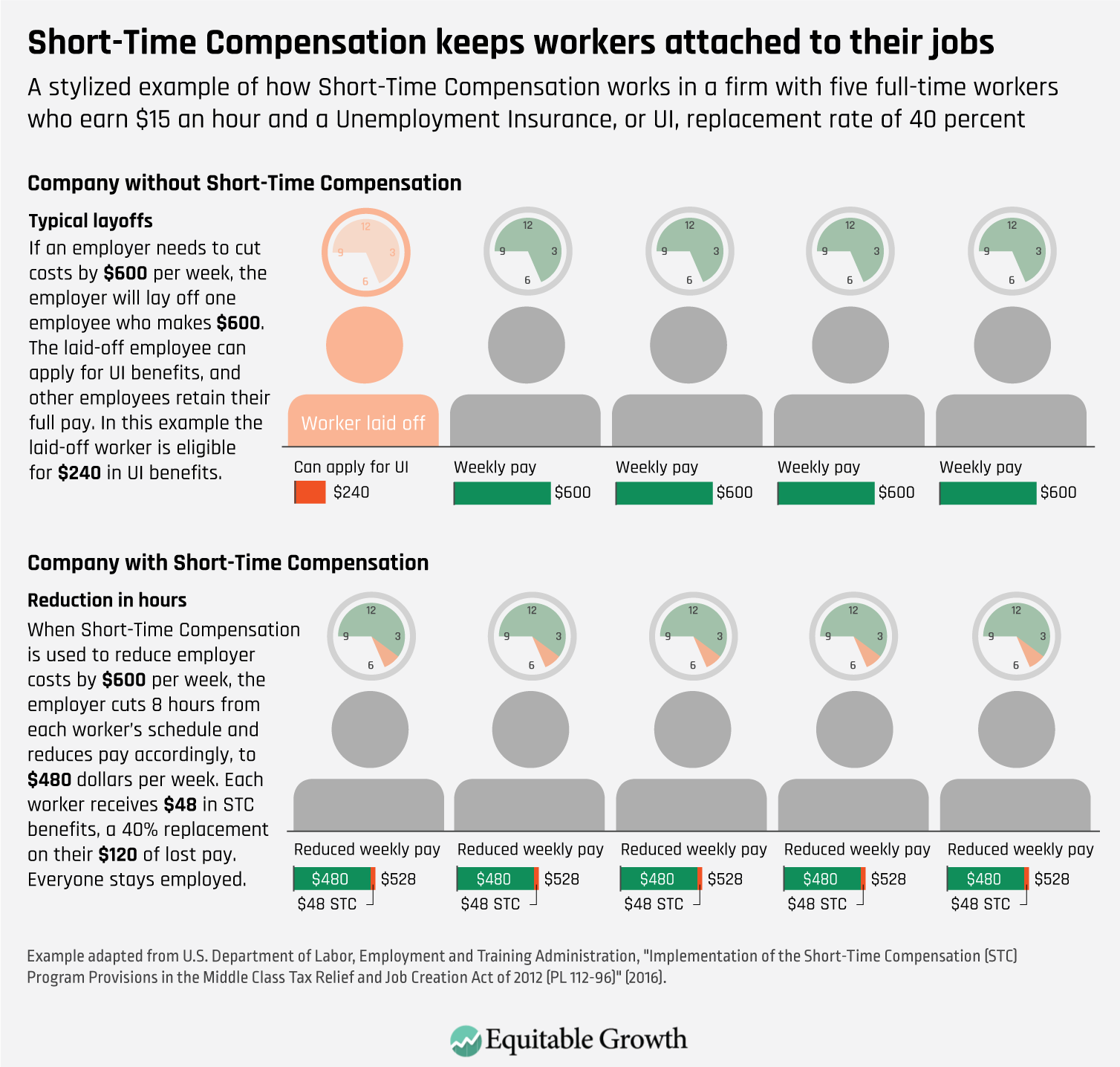

Short-Time Compensation is designed to prevent job losses by giving businesses a way to reduce their payroll costs without laying off workers. It allows employers reduce the work hours of one or more groups of employees, who, in turn, collect prorated unemployment benefits that cover a share of their lost wages.

For example, rather than laying off 20 percent of its staff to weather a downturn, an employer can choose to reduce the hours of each worker by 20 percent. If the participating employees generally work 40 hours per week, under this STC plan, they would work a 32-hour week and collect 20 percent of their corresponding weekly unemployment benefits. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Since 2021, employers also have had the ability to use Short-Time Compensation as a rehiring tool—an especially useful policy in the wake of the COVID-19 recession in which millions of U.S. workers lost their jobs or were furloughed.15 In this system, if an employer must lay off a group of employees because of a decline in demand, when demand begins to recover, it can use Short-Time Compensation to hire back the group at part-time status as it waits for demand to fully recover, rather than hiring back only a portion of the laid-off group at full-time status.

While rules vary by state, federal law requires STC plans to reduce workers’ weekly hours by a minimum of 10 percent and a maximum of 60 percent. It also establishes that employers need to maintain workers’ health and retirement benefits as if they were working their usual hours.16 States typically allow participants to collect benefits for between 26 weeks to 52 weeks.17

Short-Time Compensation is generally financed through state Unemployment Insurance trust funds, which are, in turn, funded by employer-specific payroll taxes. These payroll taxes are experience rated, which means that tax levels are determined by employers’ previous experience with the UI system. If more of an employers’ former workers have claimed Unemployment Insurance, the employer pays a higher tax.

In the past decade, however, the Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act of 2012,18 the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act of 2020,19 and the Continued Assistance for Unemployed Workers Act of 202020 created or extended provisions to encourage the use of Short-Time Compensation by, for example, federally financing 100 percent21 of benefits in states with programs and giving states the option22 to not charge claims toward a firm’s experience rating tax level.

The benefits of Short-Time Compensation

Short-Time Compensation is useful to firms, to the workers that firms employ, and to the economy as a whole. Below, we tackle each area in turn.

Benefits for firms

Short-Time Compensation helps firms retain workers and boosts employee morale. Retaining workers with firm-specific human capital assists businesses going through a temporary dip, as firms can retain their full workforce, avoid losing knowledge specific to one worker or position, better normalize operations in the aftermath of a slump, and contain costs of turnover, as described in Text Box 1.

After the downturn subsides, firms simply increase the hours of their long-time staff, who are already trained and thus more productive than new workers would be. A 2017 evaluation of Oregon’s and Iowa’s STC programs, in which researchers surveyed employers that have submitted an application to participate in the program, finds that more than 90 percent of respondents pointed to maintaining valued or skilled workers as a “very important” reason for applying to participate in an STC program.27

Further, even though layoffs are hardest on the workers who are terminated, they also affect the workers who keep their jobs. Research finds that remaining employed in a firm that experiences layoffs is associated with greater levels of stress,28 higher rates of depression and poorer physical health outcomes,29 less commitment to the firm,30 and declining job performance.31 These issues may be particularly pronounced in low-wage service industries, where baseline levels of stress are high to begin with.32

Short-Time Compensation can work as an important buffer against these negative consequences by protecting workers’ well-being and sense of job security, and preventing further declines in productivity, with evidence even showing that the program can have a positive effect on employer-worker relationships.33 Perhaps for these reasons, a 2014 survey of employers that used Short-Time Compensation in four states following the onset of the Great Recession finds that they were very satisfied with their state programs: More than 80 percent of respondents indicated that they were either “somewhat likely” or “very likely” to apply in the future.34 The more recent survey in Iowa and Oregon also reflects very high levels of employer satisfaction, finding that almost 95 percent of respondents would recommend Short-Time Compensation to other employers.35,36

Benefits for workers

Unemployment is one of the most disruptive life events that a worker can experience, often leading to economic hardship and personal distress—both of which persist even after reemployment. Workers who lose their jobs typically have a harder time finding new employment, are less likely to work full-time, and experience an important decline in earnings even if they are able to find a new job.37 And not only do layoffs in the present have consequences for earnings in the future, they also affect long-run job quality,38 psychological well-being,39 physical health,40 and social participation.41

Unemployment is especially hard on workers of color, who tend to make up a disproportionately large share of workers in low-wage service-sector industries.42 Because of centuries of discriminatory labor market practices that continue today, Black workers in particular are not only more likely than their White peers to involuntarily lose their jobs—a disparity that has become more pronounced since the 1990s43—but evidence suggests they are also more likely to experience long-term unemployment44 and deeper earnings declines during downturns.45 And because Black and Latino households tend to have less liquid wealth than their White counterparts, they also have to make greater cuts to their spending when experiencing a negative income shock such as unemployment.46

Joblessness also has a disproportionate effect on low-wage workers. These workers are both more likely to experience unemployment47 and less likely to have a financial cushion48 to weather a shortfall in earnings.

Short-Time Compensation works as a buffer against these negative outcomes by keeping workers attached to their jobs,49 maintaining their health and retirement benefits, and earning adequate income to pay the bills. In many states and localities, staying employed also allows workers to remain eligible for other income support programs, such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and housing assistance.50

In the immediate term, workers who would have otherwise been laid off are able to retain more of their prior earnings than they would if they participated in the regular Unemployment Insurance program. Further, because firms apply for and enroll workers in STC programs—as opposed to UI programs, in which workers are left to their own devices to apply—more eligible workers will successfully receive Short-Time Compensation than Unemployment Insurance. This is particularly true in the service sector, where rates of regular UI participation among unemployed workers are especially low: In 2018, just 12 percent of unemployed workers who had been employed in the leisure and hospitality industry in the previous year applied for UI benefits.51

Benefits for the overall economy

In addition to supporting individual workers and firms, Short-Time Compensation has the potential to stabilize the entire economy amid downturns. By allowing cash-strapped businesses to stay afloat while maintaining their workforce, spreading income losses across a wider pool of workers so that they are less severe, and circumventing the short- and long-term consequences of layoffs, the program can be a tool to make economic shocks less severe and help drive a faster and more equitable recovery.

By keeping workers attached to their jobs, STC programs mechanically increase levels of employment. Persistent levels of long-term unemployment can depress employment in the long run because job-finding rates are lower for those who experience longer spells without a job—a result that holds when comparing workers with similar demographic characteristics and career trajectories.52 Short-Time Compensation, then, not only reduces unemployment for today’s workers, but also protects tomorrow’s economy.

Additionally, Short-Time Compensation can sustain the amount of money circulating in the economy during a downturn, supporting aggregate demand and creating yet another channel through which to prevent job losses. How does this work? By replacing a portion of the wages workers otherwise would have lost, Short-Time Compensation and Unemployment Insurance generally act as buffers against sharp drops in consumer spending, which, in turn, prevents further job losses by sustaining demand for goods and services.53 Income support programs can therefore set in motion a virtuous cycle in which the economic activity generated through government spending protects jobs and earnings from economic downturns, stabilizing the entire economy.

Indeed, evidence from a range of countries shows Short-Time Compensation’s effectiveness in preventing job losses across the economy as a whole.Researchers studying Italy’s program, for example, estimate that had there not been an STC program in place, the country’s unemployment rate would have been almost 2 percentage points higher during the Great Recession.54 Similarly, economists studying the French STC program found that it saved jobs by helping credit-constrained firms survive the Great Recession and recover more quickly in its aftermath.55

Likewise, during the Great Recession, Germany experienced a sharper drop in economic growth than the United States, but its unemployment rate actually declined between 2007 and 2009.56 This outcome was driven by the European country’s labor market policies in response to the crisis—which included the widespread use of Short-Time Compensation.57

In the U.S. context, researchers have found that the program has a positive effect on overall employment. In a 2013 study, for example, Katherine Abraham of the University of Maryland and Susan Houseman of the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research find that during the Great Recession, manufacturing employers in states with Short-Time Compensation were more likely to adjust to the economic downturn by cutting hours of work rather than by terminating workers.58 The two economists calculate that Short-Time Compensation saved the equivalent of about 22,000 full-time jobs in 2009, the worst year of the crisis.

Research has yet to determine how the program would operate in the low-wage service sector. Yet Abraham and Houseman estimate that if program usage had been as widespread across the country as it was in Rhode Island—the state where the greatest share of workers received Short-Time Compensation—it would have saved the equivalent of 220,000 full-time jobs in 2009. If Short-Time Compensation had been used at a similar rate as it was in Germany or Italy, that number would have climbed to almost 1 million.

Challenges facing Short-Time Compensation in the United States

Attention to Short-Time Compensation in the United States has risen and fallen over the past 40 years alongside the business cycle, with recessions triggering policymakers’ and analysts’ interest in expanding and strengthening it. In 2020, amid the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing recession, more than half a million U.S. workers received Short-Time Compensation benefits—a historical high.

Still, as effective as worksharing programs have been for some firms and workers, and despite the potential they have to support the economy as a whole, only about half of U.S. states have operational Short-Time Compensation programs. Even in states that do administer these benefits, participation rates are low, particularly outside of the manufacturing sector. The limited capacity of STC programs, interstate variation between programs, and the lack of prior experience with Short-Time Compensation make it difficult for large, service-sector employers—such as the ones most affected by the COVID recession—to access these important programs.

Below, we detail the various challenges facing STC programs in the United States, beginning with the fact that Short-Time Compensation is underused across the U.S. economy and across U.S. states.

Short-Time Compensation is underused

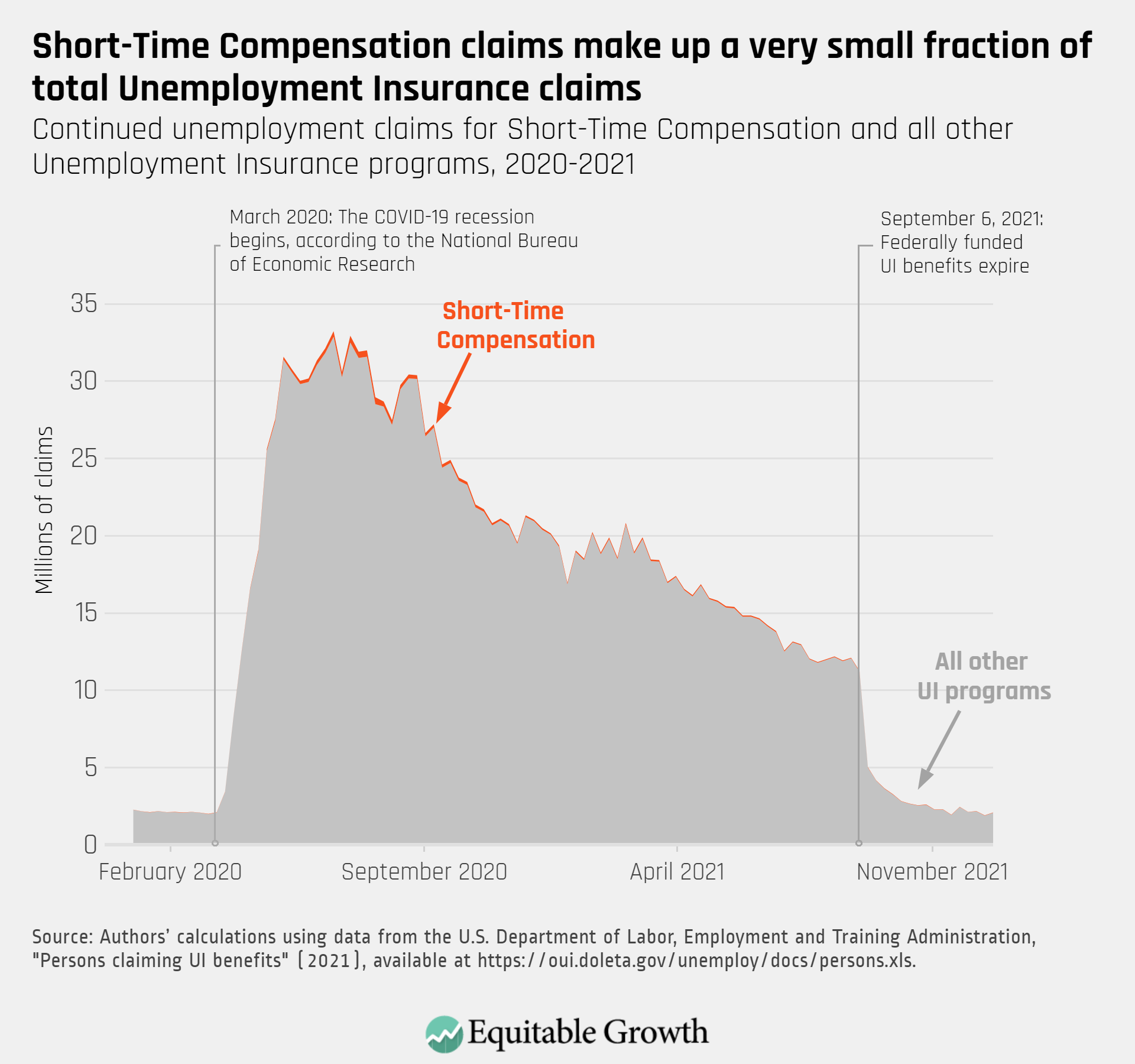

Even though use of STC programs tends to grow both in absolute numbers and relative to other Unemployment Insurance programs during recessions, Short-Time Compensation makes up a very small fraction of the broader Unemployment Insurance system.59 In July 2020, for instance, the proportion of continued UI claims represented by Short-Time Compensation peaked at 1.6 percent but, by November 2020, had dropped to pre-COVID recession levels and remained at this level—around half a percentage point—through 2022. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

Researchers have found that two major reasons why Short-Time Compensation is not more widely used in the states that offer it are that most employers are not aware of the program and that participating in it can often raise firms’ payroll taxes.60 In addition, states’ limited staffing capacity and outdated processing systems—some states have not yet automated the way they process Short-Time Compensation claims—create administrative bottlenecks precisely when businesses and workers need the program the most, and the most urgently.61 As such, the U.S. institutional design creates few incentives for employers to take up job-retention schemes such as Short-Time Compensation.

More broadly, U.S. labor market institutions tend to be much less protective of workers than those of peer countries, making layoffs an easy way for firms to cut costs when experiencing a slump. According to the Employment Protection Legislation index—a measure created by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development to capture the strength of employment protection legislation—the United States has the least robust job regulations against dismissals of any member country.62 In other words, the United States is an outlier in terms of offering workers few protections against layoffs, as many states do not require employers to provide a reason for termination, and workers are generally not guaranteed severance pay or a notice period prior to a dismissal.

Short-Time Compensation is especially underused in the low-wage service sector

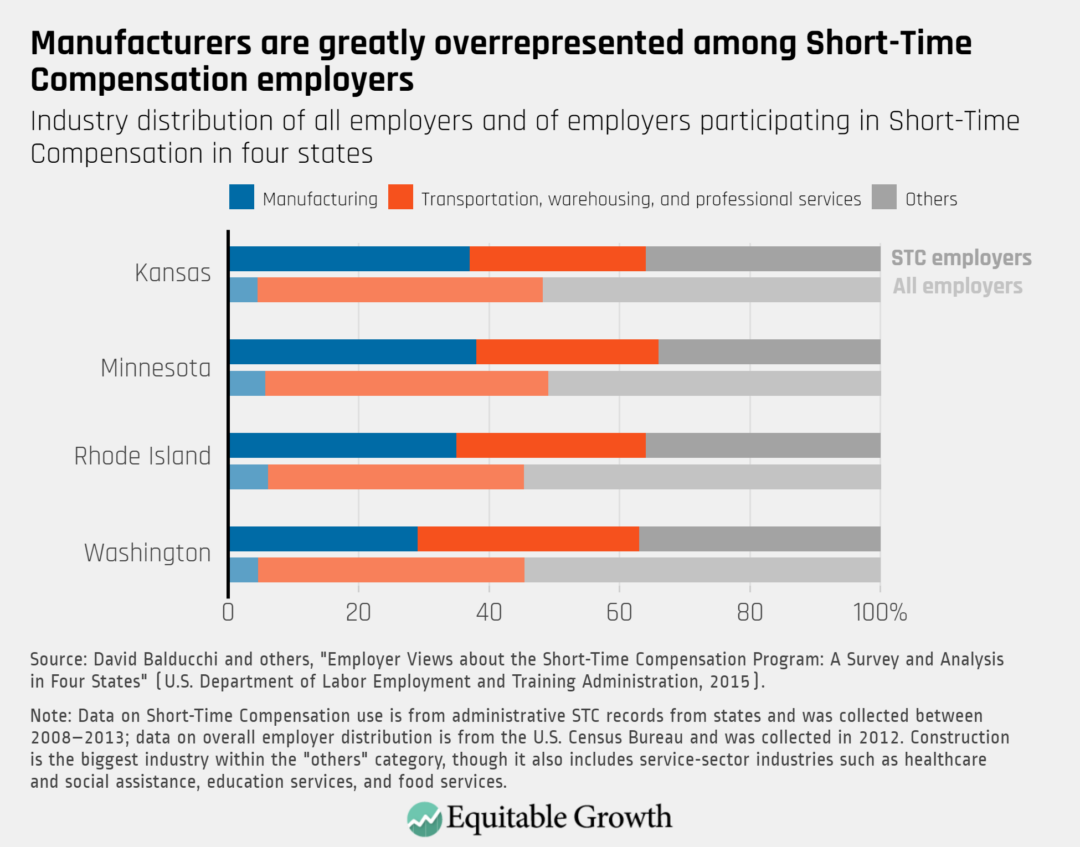

A 2014 study of STC employers in four states commissioned by the U.S. Department of Labor provides some of the best available evidence on use of the program by industry.63 Looking at administrative data, the authors find that manufacturers are greatly overrepresented among STC beneficiaries. For example, in Kansas, more than a third of employers participating in the state’s STC program are in the manufacturing industry, but less than 5 percent of employers in the state are manufacturers. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

The same 2014 study also finds that across all four states, the low-wage service sector is underrepresented in the program. In fact, it finds that only 8 percent of survey respondents were in the retail industry, and less than 1 percent were in accommodation and food services. That the program is most used by manufacturers suggests that men and White workers are also disproportionately represented among its beneficiaries: 80 percent of workers in manufacturing are White and 70 percent are men.64

Why do employers in goods-producing industries make up such a large share of STC employers, relative to employers in service-providing industries? Firms that employ service-sector workers may not participate because they see the benefits as being too low to make taking the time to navigate the program and potentially experiencing a tax increase worthwhile. Many low-wage service workers are employed in positions that do not require high levels of formal education and perform tasks that their employers do not consider to be highly specialized.65 Given the high rates of turnover in low-wage service industries, employers may therefore believe that it is not worth participating in a program that has the objective of helping workers and firms maintain their employment relationships though downturns.

Yet, as described above, this view is short-sighted. Failing to retain low-wage workers is associated with high turnover costs, poor job performance, operational mishaps, and weaker sales and profits.66 On the other hand, prompting employers to retain and invest in their lower-paid workers would drive a virtuous cycle in which workers in good, secure jobs are better able to help build more prosperous and resilient businesses.67

Instead, however, Short-Time Compensation is underused in the largest sector of the U.S. economy—the service sector—hampering its ability to meet the needs of employers, workers, and the broader economy.

The STC system is fragmented and complex

As of early 2022, only 26 states and Washington, DC have operational STC programs. This fragmentation means that multistate firms—including the country’s largest employers, for which many of the nation’s service-sector employees work—must navigate a separate bureaucracy for each state in which they operate that offers an STC option. This is a barrier to take-up for multistate employers.

Additionally, lack of information about how to apply for the program and the time it takes to navigate each system slow Short-Time Compensation’s ability to respond to macroeconomic shocks in a timely manner.

This fragmentation and complexity also leads to racial inequity. Today, only two out of the 10 U.S. states with the highest share of Black workers have STC programs in place, putting this useful income support program out of reach for millions of Black workers.68 (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6

Recommendations to improve U.S. Short-Time Compensation

To make Short-Time Compensation work for the U.S. service sector—and thus the economy as a whole—we need intervention that is broad, as well as intervention that is tailored to the low-wage service sector. Broad interventions would improve the reach and scale of Short-Time Compensation, allowing the program to absorb broad swaths of the workforce when the economy contracts. Interventions that are specifically tailored to service-sector employers and workers will help ensure that these workers—who are disproportionately low-wage workers and workers of color—are at the center of U.S. economic recoveries.

Below, we detail a handful of recommended interventions that would accomplish the above goals, including establishing a federal STC program, making STC programs more user-friendly for employers and workers alike, and conducting outreach and further research on STC programs.

Establish a federal STC program

One of the clearest lessons from the COVID-19 crisis for Short-Time Compensation is that the program failed to operate smoothly for multistate employers. A federal STC program would be easier for multistate employers to navigate and would allow a single entity to ensure that changes to program design are implemented consistently and well. It also would allow for the STC program to efficiently scale up—a necessary step for equipping the program to absorb large numbers of service-sector workers.

Should it not be possible to establish a federal STC program, steps could still be taken to create a more streamlined STC experience across states. States could be required to participate in Short-Time Compensation, so that the program would be available in all states. Benefits disbursed through Short-Time Compensation could be 100 percent federally financed to make this option more appealing to states. The U.S. Department of Labor could also encourage states to align program requirements and systems across state lines to streamline the application process.

Require employers to keep STC plans on file

In moments of economic crisis, decision-makers at firms are often overwhelmed with the number of decisions they need to make. In an economic context where churn is common, laying off workers is likely to be perceived as a more intuitive and simpler step than navigating a new government program and developing a plan for reducing work hours across the workforce in the midst of a company crisis.

Requiring employers to put plans for participating in Short-Time Compensation on file annually means employers will become familiar with the STC program before they are facing tough decisions about layoffs. It also ensures that they have a clear plan to turn to when determining how to implement Short-Time Compensation at their business.

Make STC program design more user-friendly for employers

Firms are more likely to participate in Short-Time Compensation if its design meets their needs. Making STC program design more user-friendly for employers can increase the scale of the STC program, so that it is able to absorb more workers, including service-sector workers, in times of economic crisis.

One step that would make STC program design more appealing to employers is waiving experience rating for benefits claimed through the STC program. As detailed above, states’ Unemployment Insurance programs are funded through taxes that employers pay on each of their workers’ earnings, or payroll taxes. The level of the tax is set by a measure of the employers’ previous experience with the UI program, called an experience rating: If more of an employers’ former workers have claimed Unemployment Insurance, the employer pays a higher tax. By not counting Short-Time Compensation toward employers’ experience ratings, states are effectively lowering the price employers pay to enroll their workers in the program, creating stronger incentives for participation.

To further tailor STC programs to meet employers’ needs, there should be greater flexibility in terms of access and allowed reductions in work hours.69 In most states, to remain eligible for the STC program, employers currently can only reduce their employees’ work participation by up to 60 percent. This requirement does not meet the needs of many employers during severe macroeconomic contractions—employers may reduce their workforce by greater amounts to meet drops in demand and production. Further, some states do not allow employers at the maximum experience rating to participate in Short-Time Compensation, despite the fact that they and their employees may benefit from the program. These rules could be eliminated to extend the benefits of Short-Time Compensation to all employers.

Additionally, if the process of signing up to participate in the program is simple and tailored to the needs of employers, they will be more likely to participate. For instance, all employers should have the option to apply for the program online and should be confident that there will be enough staff in the state STC office to provide applicants and program participants with technical assistance.70 A more user-centered design experience,71 investments in online help desks and other improvements to online application processes, and even perhaps default approval72 of STC applications could further increase the ease of participation in Short-Time Compensation for employers. In addition, states should ensure their STC websites offer employers and workers updated and clear information on the benefits of and process for applying for Short-Time Compensation.73

Make STC program design more user-friendly for workers

When Short-Time Compensation is accessible to all workers, including the most vulnerable, it is more successful in supporting firms, workers, and the macroeconomy. States can work to decrease the administrative barriers74 that make it difficult for workers—particularly those who face obstacles to successfully navigating bureaucracies,75 including groups that are overrepresented in service jobs, such as immigrant workers who may have limited English proficiency or competing demands for their time—to successfully claim the benefits to which they are entitled.76 Though it is the employer who enters into STC arrangements with the state, the benefits are paid directly to workers, who may encounter hurdles when making their claims.77

Program rules also can be altered to make Short-Time Compensation accessible to low-wage service-sector workers, who may hold multiple jobs in order to make ends meet. Currently, wages earned from second jobs offset benefits paid out through STC programs, disadvantaging workers who hold multiple jobs relative to those who can afford to hold a single job. By eliminating this offset, the program would be more equitable for multiple-job-holders and would further eliminate the need for workers to participate in weekly certifications—thus potentially reducing the bureaucratic hurdles workers face when claiming benefits.

Conduct outreach to service-sector employers about STC programs

Even if the design and administration of Short-Time Compensation are modified to increase financial incentives for firms to participate and decrease their transaction costs, firms will not participate if they are not aware of the program. The federal government could do its own outreach and provide grant funding and incentives to states to conduct outreach campaigns targeting the service sector, modeled after those provided through the Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act of 2012. With these funds, states could then launch marketing campaigns to increase employer awareness about the benefits of Short-Time Compensation.

When states launch coordinated campaigns to increase awareness about Short-Time Compensation, these campaigns can have meaningful effects. For example, a 2017 study commissioned by the U.S. Department of Labor and conducted in Iowa and Oregon used experimental and quasi-experimental methods to determine how employer outreach affected program take-up and finds that outreach campaigns are effective at increasing employer awareness about Short-Time Compensation.78 Using simple methods, such as informational mailings, website banners, and webinars, the states increased employers’ awareness of the program by 15 percentage points to 30 percentage points. In Oregon, where economic conditions were weaker than in Iowa, STC plan adoption increased between 58 percent and 113 percent 2 years after the start of the intervention.79

Effective outreach also could lead to a more proportional distribution of STC usage across employers, making it more likely that the businesses that employ low-wage service-sector workers participate in the program. For example, as Figure 5 above shows, the manufacturing industry in Washington state is less dominant among STC employers than in the other three states that were studied—a trend the study’s authors attribute to Washington’s robust employer outreach efforts.

Conduct research, including a federal STC pilot program across multiple states

More research is needed to identify the policies to best ensure that Short-Time Compensation fulfills its potential to benefit firms and workers in the service sector and across the U.S. economy. In contrast to other high-income countries with robust STC schemes, research on the U.S. system is limited.

First, more research is needed to gain insight into the outcomes firms experience after taking up the program. Do firms that participate in Short-Time Compensation have a greater likelihood of surviving a downturn? How likely is it for businesses to lay off workers after participating in the program?

Little is also known about workers’ perception of and experience with the program. We need more data on the workers who access Short-Time Compensation, including their race, gender, income level, union membership status, occupation, and industry. Data on the career and earnings’ trajectories of workers who participate in STC plans, as well as data on workers’ experience navigating the program, would also be helpful.

Research on peer countries’ STC schemes provides valuable insight into how robust programs affect labor market dynamics, but it is not clear whether scaling up the program in the United States would have the same effects. Given that there are important differences between the U.S. institutional context and that of many of its peer countries, more research on the U.S. context is needed. This includes:

- Collecting more detailed information about program participants: What are the characteristics of employers and workers who participate in the program? Who is left out?

- Conducting more research on program outcomes: Does Short-Time Compensation prevent layoffs or merely delay them? Does it result in long-run cost savings for firms? How does Short-Time Compensation affect firm survival, turnover, wage scarring, material hardship, and stress? How do these outcomes vary between service-sector and non-service-sector industries? How do outcomes differ between high- and low-wage service-sector workers?

- Learning more about effective program design: What would make the program most appealing to employers and most accessible to workers? How would a more appealing, accessible program affect the other outcomes under examination?

While descriptive research on firm experiences with Short-Time Compensation can make—and has made—meaningful contributions to our understanding of STC programs and benefits, a rigorously evaluated federal STC pilot program operating across multiple states would provide important insights into both the dynamics of operating a national STC program, such as the one described earlier in this section, and the effects of such a program for workers and firms in the service sector.

Conclusion

Short-Time Compensation is an important program with enormous potential to strengthen business vitality, economic security, and macroeconomic stability, as well as protect worker economic and psychological well-being. Yet Short-Time Compensation is underused, particularly in the low-wage service sector. Rates of participation in Short-Time Compensation in the United States trail far behind those in peer European nations, where the program is effectively used to save jobs and stabilize economies during downturns.

To reap the full benefits of Short-Time Compensation, it is essential to strengthen the program in a way that includes service-sector workers, who make up an increasingly large segment of the overall U.S. workforce and whose receipt of Short-Time Compensation is likely to provide the greatest boost to the macroeconomy.

While the interventions described in this report are a good starting place, more evidence and data would allow for a more nuanced understanding of how the STC system could best meet the needs of the modern U.S. economy and one of its most prominent components—the service sector. Conducting research into how Short-Time Compensation affects long-run firm and worker outcomes, as well as how STC programs in the United States operate similarly or differently from European worksharing programs, we can better understand the potential of the program to shore up the U.S. economy and identify key elements of program design.

By ramping up efforts to collect data and conduct research on the program in the U.S. context, the U.S. Department of Labor could more precisely identify how to strengthen Short-Time Compensation in the United States. Piloting a multistate program that incorporates the changes proposed above could allow the department to determine how to best scale such an initiative across all states.

Acting with the information we have now, however, there is much that policymakers can already do. Establishing a federal STC program, making program design friendlier to employers and workers, and conducting outreach to service-sector employers to increase program awareness would increase the program’s scale, scope, and ability to respond to downturns—including and especially the COVID recession, which disproportionately harmed low-wage service-sector workers.

Indeed, the COVID pandemic highlighted the fact that Short-Time Compensation was not living up to its potential in the United States, in part because it was not reaching service-sector workers. Regardless of what factors drive the next economic contraction in the United States, there is little doubt that a strengthened Short-Time Compensation program would help combat the effects of a downturn for firms, workers, and the economy as a whole—both in the immediate term and in the long run.

Acknowledgements

The Washington Center for Equitable Growth would like to thank the researchers, scholars, and policy experts who provided valuable feedback. Their generous feedback and expertise informed the content of this report. Specifically, unpublished ideas from Kitty Richards and Lily Roberts informed our policy recommendations. Additionally, special thanks are owed to Katharine Abraham, Heather Boushey, Judy Conti, Jenna Gerry, Annelies Goger, Elizabeth Pancotti, Wayne Vroman, George Wentworth, and Steve Woodbury for their insightful feedback.

End Notes

1. Elise Gould and Melat Kassa, “Low-wage, low-hours workers were hit hardest in the COVID-19 recession” (Washington: Economic Policy Institute, 2021), available at https://www.epi.org/publication/swa-2020-employment-report/.

2. Gene Falk and others, “Unemployment rates during the COVID-19 pandemic” (Washington: Congressional Research Service, 2021), available at https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R46554.pdf.

3. For example, the leisure and hospitality industry—which lost the largest number of jobs during the recession—shed 8.2 million jobs between February 2020 and April 2020. As such, the leisure and hospitality workforce shrunk by almost 50 percent during the COVID-19 recession. A year after the onset of the crisis, in February 2021, leisure and hospitality was still the industry facing the most severe shortfall in employment (-3.4 million jobs), followed by government (-1.4 million jobs), education and health services (-1.3 million jobs), professional and business services (-771,000 jobs), manufacturing (-561,000 jobs), other services (-446,000 jobs), retail trade (-362,600 jobs), construction (-308,000 jobs), wholesale trade (-260,500 jobs), information (-248,000 jobs), transportation and warehousing (-164,700 jobs), financial activities (-105,000 jobs), mining and logging (-101,000 jobs) and, lastly, utilities (-8,600 jobs).

4. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment and average hourly earnings by industry” (Washington: Department of Labor, 2022), available at https://www.bls.gov/charts/employment-situation/employment-and-average-hourly-earnings-by-industry-bubble.htm.

5. Andrew Van Dam, “The seven industries most desperate for workers,” The Washington Post, June 14, 2021, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2021/06/15/industries-with-worker-shortages/.

6. George Wentworth, Claire McKenna, and Lynn Minick, “Lessons learned: Maximizing the potential of work-sharing in the United States” (Washington: National Employment Law Project, 2014), available at https://s27147.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Lessons-Learned-Maximizing-Potential-Work-Sharing-in-US.pdf.

7. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “OECD Employment outlook 2020: Worker security and the COVID-19 crisis” (2020), available at https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/employment/oecd-employment-outlook-2020_1686c758-en.

8. Wentworth, McKenna, and Minick, “Lessons learned: Maximizing the potential of work-sharing in the United States.”

9. Some states may have nonoperational STC programs. For example, in 2020, Vermont deactivated its STC program, meaning that it can resume operations through legislative action by the Vermont General Assembly. According to the U.S. Department of Labor’s ETA 5159 report on Unemployment Insurance claims and payment activities, in the first quarter of 2022, the following jurisdictions reported claims and payment activities to the department: Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York state, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Texas, Washington, DC, Washington state, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

10. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Annual total separations rates by industry and region, not seasonally adjusted” (Washington: Department of Labor, 2022), available at https://www.bls.gov/news.release/jolts.t16.htm.

11. Julie Whittaker, “Compensated work sharing arrangements (Short-Time Compensation) as an alternative to layoffs” (Washington: Congressional Research Service, 2016), available at https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R40689.pdf.

12. Katelynn Harris, “Forty years of falling manufacturing employment,” Beyond the Numbers 9 (16) (2020), available at https://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/volume-9/forty-years-of-falling-manufacturing-employment.htm.

13. Ibid.

14. In 2019, the average hourly earnings for all private-sector employees were $27.99. For private service-providing industries, average hourly earnings were the following: wholesale trade ($31.36), retail trade ($19.70), transportation and warehousing ($24.71), utilities ($41.72), information ($42.19), financial activities ($35.94), professional and business services ($33.68), education and health services ($27.62), leisure and hospitality ($16.56), and other services ($25.21).

15. U.S. Employment and Training Administration Agency, “Unemployment Insurance program letter no. 10-20, change 2” (Washington: Department of Labor, 2021), available at https://wdr.doleta.gov/directives/attach/UIPL/UIPL_10-20_Change_2.pdf.

16. National Governor’s Association, “Short-Time Compensation programs as a COVID-19 response and recovery strategy” (2020), available at https://www.nga.org/center/publications/short-term-compensation-programs-covid-19/.

17. U.S. Employment and Training Administration, “Implementation of the Short-Time Compensation (STC) program provisions in the Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act of 2012.” (Washington: Department of Labor, 2016), available at https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/docs/stc_report.pdf.

18. Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act of 2012, HR 3630, 112th Cong. (2012), available at https://www.congress.gov/112/plaws/publ96/PLAW-112publ96.pdf.

19. U.S. Employment and Training Administration Agency, “Unemployment Insurance program letter no. 21-20” (Washington: Department of Labor, 2020), available at https://wdr.doleta.gov/directives/attach/UIPL/UIPL_21-20.pdf.

20. U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, “Section by section COVID relief Continued Assistance to Unemployed Workers” (n.d.), available at https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/UI,%2012-21-20,%20Section%20by%20Section%20COVID%20Relief%20Continued%20Assistance%20to%20Unemployed%20Workers.pdf.

21. U.S. Department of Labor, “U.S. Department of Labor issues additional guidance about Short-Time Compensation program provisions,” Press release, May 4, 2020, available at https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/eta/eta20200504.

22. U.S. Employment and Training Administration Agency, “Unemployment Insurance program letter no. 21-20.”

23. Kate Bahn and Carmen Sanchez Cumming, “Improving U.S. labor standards and the quality of jobs to reduce the cost of employee turnover to U.S. companies” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2020), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/improving-u-s-labor-standards-and-the-quality-of-jobs-to-reduce-the-costs-of-employee-turnover-to-u-s-companies/.

24. Blake Frank, “New ideas for retaining store-level employees” (Coca-Cola Company Retailing Research Council, 2000), available at https://www.ccrrc.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/24/2014/02/New_Ideas_for_Retaining_Store-Level_Employees_2000.pdf.

25. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Annual total separations rates by industry and region, not seasonally adjusted.”

26. David Balducchi and others, “Employer views about the Short-Time Compensation program: A survey and analysis in four states” (Columbia, MD: IMAQ International, 2015), available in https://impaqint.com/sites/default/files/files/ETAOP-2016-01_Final-Report-Acc.pdf.

27. Susan Houseman and others, “Demonstration and evaluation of the Short-Time Compensation program in Iowa and Oregon” (Washington: U.S. Department of Labor, 2017), available at https://research.upjohn.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1081&context=externalpapers.

28. Sepideh Modrek and Mark Cullen, “Job insecurity during recessions: effect on survivors’ work stress,” BCM Public Health 13 (923) (2013): 1–11, available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1471-2458-13-929.

29. Leon Grunberg, Sarah Moore, and Edward Greenberg, “Differences in psychological and physical health among layoff survivors: the effect of layoff contact,” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 6 (1) (2001): 15–25, available at https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2000-16892-002.

30. Hannah Knudsen and others, “Downsizing survival: The experience of work and organizational commitment,” Social Inquiry 73 (2003): 265–283, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/action/showCitFormats?doi=10.1111%2F1475-682X.00056.

31. Sandra Sucher and Shalene Gupta, “Layoffs that don’t break your company,” Harvard Business Review (2018), available at https://hbr.org/2018/05/layoffs-that-dont-break-your-company.

32. Jennifer Cheang, “Manufacturing, retail, and food and beverage industries rank worst for workplace mental health” (Alexandria, VA: Mental Health America, 2017), available at https://mhanational.org/blog/manufacturing-retail-and-food-and-beverage-industries-rank-worst-workplace-mental-health.

33. Fred Best, Reducing workweeks to Prevent Layoffs (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998).

34. Balducchi and others, “Employer views about the Short-Time Compensation program: A survey and analysis in four states.”

35. Houseman and others, “Demonstration and evaluation of the Short-Time Compensation program in Iowa and Oregon.”

36. While the opinions of participating employers cannot be generalized to nonparticipants—who indeed may have considered and rejected participation—because Short-Time Compensation is not available in a large number of states, enrollment levels are so low, and so many employers lack information about the program, it is likely that many nonparticipating employers would share the positive perceptions of the participating employers were they to participate. Indeed, evidence suggests that low awareness of the program is one of the most important barriers to employer participation.

37. Henry Farber, “Job loss in the Great Recession and its aftermath: U.S. evidence from the Displaced Workers Survey.” Working Paper No. 589 (Princeton University, 2015), available at https://dataspace.princeton.edu/bitstream/88435/dsp01zk51vk05h/5/589.pdf.

38. Jennie Brand, “The effects of job displacement on job quality: Findings from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study,” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 24 (3) (2006): 275–298, available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0276562406000291.

39. Andreas Knabe and Steffen Rätzel, “Scarring or Scaring? The psychological impact of past unemployment and future unemployment risk,” Economica 78 (310) (2011): 283–293, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2009.00816.x.

40. Daniel Sullivan and Till von Wachter, “Job Displacement and Mortality: An Analysis Using Administrative Data,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 124 (3) (2009): 1265–1306, available at https://academic.oup.com/qje/article-abstract/124/3/1265/1905153?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

41. Jennie Brand and Sarah Burgard, “Job Displacement and Social Participation over the lifecourse: Findings for a cohort of joiners,” Social Forces 87 (1) (2008): 211–242, available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2935181/.

42. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employed persons by detailed industry, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity” (Washington: Department of Labor, 2021), available at https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat18.htm.

43. Elizabeth Wrigley Field and Nathan Seltzer, “Unequally insecure: Rising Black/White disparities in job displacement, 1981-2017.” Working Paper (Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2020), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/working-papers/unequally-insecure-rising-black-white-disparities-in-job-displacement-1981-2017/.

44. Alan Krueger, Judd Cramer, and David Cho, “Are the long-term unemployed on the margins of the labor market?” Working Paper (The Brookings Institution, 2014), available at https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/2014a_krueger.pdf.

45. Jared Bernstein and Janelle Jones, “The Impact of the COVID19 Recession on the jobs and incomes of persons of color” (Washington: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2020), available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/full-employment/the-impact-of-the-covid19-recession-on-the-jobs-and-incomes-of-persons-of.

46. Peter Ganong and others, “Wealth, race and consumption smoothing during typical income shocks.” Working Paper (Becker Friedman Institute, 2020), available at https://bfi.uchicago.edu/working-paper/wealth-race-and-consumption-smoothing-of-typical-income-shocks/.

47. Ben Zipperer and Elise Gould, “Without fast action from Congress, low-wage workers will be inedible for unemployment benefits during the coronavirus crisis” (Washington: Economic Policy Institute, 2020), available at https://www.epi.org/blog/without-fast-action-from-congress-low-wage-workers-will-be-ineligible-for-unemployment-benefits-during-the-coronavirus-crisis/#:~:text=The%20expansion%20is%20necessary%20and,eligible%20to%20collect%20UI%20benefits.

48. Christina Patterson, “The most exposed workers in the coronavirus recession are also key consumers: Making sure they get help is key for fighting the recession” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2020), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/the-most-exposed-workers-in-the-coronavirus-recession-are-also-key-consumers-making-sure-they-get-help-is-key-to-fighting-the-recession/.

49. Though there are concerns that Short-Time Compensation delays, rather than prevents, job losses, that question has not been settled by researchers. In addition, there are important benefits to postponing layoffs, since it lessens the risk of mass job losses—events that are greatly disruptive for both individual workers and labor markets.

50. Heather Han, “Navigating work requirements in safety net programs” (Washington: Urban Institute, 2019), available at https://www.urban.org/research/publication/navigating-work-requirements-safety-net-programs.

51. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Characteristics of Unemployment Insurance applicants and benefit recipients news release – 2018,” Press release, September 25, 2019, available at https://www.bls.gov/news.release/uisup.htm.

52. Katherine Abraham and others, “The consequences of long-term unemployment: Evidence from linked survey and administrative data.” Working Paper No. 22665 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2018), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w22665.

53. Diana Farrell and others, “The unemployment benefit boost: Trends in spending and saving when the $600 supplement ended” (JP Morgan Chase & Co. Institute, 2020), available at https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/voices.uchicago.edu/dist/1/801/files/2018/08/Institute-UI-Benefits-Boost-Policy-Brief.pdf.

54. Giulia Giupponi and Camille Landais, “Subsidizing labor hoarding in recessions: The employment & welfare effects of short time work.” Discussion Paper No. DP13310 (Center for Economic and Policy Research, 2018), available at https://econ.lse.ac.uk/staff/clandais/cgi-bin/Articles/STW.pdf.

55. Pierre Cahuc, Francis Kramarz, and Sandra Nevoux, “When Short-time works,” VoxEU, July 16, 2018, available at https://voxeu.org/article/when-short-time-work-works.

56. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Unemployment rate” (Paris: OECD data, 2022), available at https://data.oecd.org/unemp/unemployment-rate.htm.

57. Dean Baker, “Work Sharing: The quick route back to full employment” (Washington: Center for Economic and Policy Research, 2011), available at https://cepr.net/documents/publications/work-sharing-2011-06.pdf.

58. Katherine Abraham and Susan Houseman, “Short-Time Compensation as a Tool to Mitigate Job Loss? Evidence on the U.S. Experience during the Recent Recession.” Working Paper 12-181 (W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 2013), available at https://research.upjohn.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1198&context=up_workingpapers.

59. Wentworth, McKenna, and Minick, “Lessons learned: Maximizing the potential of work-sharing in the United States.”

60. Houseman and others, “Demonstration and evaluation of the Short-Time Compensation program in Iowa and Oregon.”

61. Ibid.

62. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “OECD Employment outlook 2020: Worker security and the COVID-19 crisis.”

63. Balducchi and others, “Employer views about the Short-Time Compensation program: A survey and analysis in four states.”

64. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employed persons by detailed industry, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity.”

65. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Educational attainment for workers 25 years and older by detailed occupation, 2018 – 2019” (Washington: Department of Labor, 2021), available at https://www.bls.gov/emp/tables/educational-attainment.htm.

66. Katie Bach, Sarah Kalloch, and Zeynep Ton, “The financial case for good retail jobs,” Harvard Business Review, June 26, 2019, available at https://hbr.org/2019/06/the-financial-case-for-good-retail-jobs?ab=at_articlepage_relatedarticles_horizontal_slot3.

67. Ibid.

68. Emily Rolen and Mitra Toosi, “Blacks in the labor force” (Washington: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2018), available at https://www.bls.gov/careeroutlook/2018/article/blacks-in-the-labor-force.htm.

69. Wentworth, McKenna, and Minick, “Lessons learned: Maximizing the potential of work-sharing in the United States.”

70. David Balducchi and Christopher O’Leary, “Streamlining Administration of Short-Time Compensation: What’s right with Kansas?” (Kalamazoo, MI: W.E Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 2020), available at https://www.upjohn.org/research-highlights/streamlining-administration-short-time-compensation-whats-right-kansas.

71. Julia Simon-Mishel and others, “Centering workers – how to modernize Unemployment Insurance technology” (New York City: The Century Foundation, 2020), available at https://tcf.org/content/report/centering-workers-how-to-modernize-unemployment-insurance-technology/.

72. Till von Wachter, “A proposal for scaling enrollments in work sharing (Short-Time Compensation) programs during the Covid-19 crisis: The case of California” (Los Angeles: University of California, Los Angeles, 2020), available at http://www.econ.ucla.edu/tvwachter/covid19/Scaling_STC_memo_vonWachter.pdf.

73. Wentworth, McKenna, and Minick, “Lessons learned: Maximizing the potential of work-sharing in the United States.”

74. Julia Simon-Michel and others, “Centering workers – how to modernize Unemployment Insurance technology.”

75. National Employment Law Project, “Work-Sharing: An Unemployment Insurance program solution for rehiring and addressing budget cuts,” Youtube video, 1:12:15, October 27, 2020, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wCR-BZVrEqs.

76. Abraham Mosisa, “Foreign-born workers in the U.S. labor force” (Washington: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2013), available at https://www.bls.gov/spotlight/2013/foreign-born/home.htm.

77. Amanda Fischer and Alix Gould-Werth, “Broken plumbing: How systems for delivering economic relief in response to the coronavirus recession failed the U.S. economy” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2020), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/broken-plumbing-how-systems-for-delivering-economic-relief-in-response-to-the-coronavirus-recession-failed-the-u-s-economy/.

78. Houseman and others, “Demonstration and evaluation of the Short-Time Compensation program in Iowa and Oregon.”

79. In Iowa, no effects were observed. The research team attributes this lack of effect to the strong economy, historically low levels of STC participation, capacity constraints, and other institutional factors.

80. “Short Time Compensation Programs, Employment and Training Administration, Labor,” available at https://www.usaspending.gov/federal_account/016-0168 (last accessed May 9, 2022).

81. Pawel Krolikowski and Anna Weixel, “Short-Time Compensation: An Alternative to Layoffs during COVID-19” (Cleveland: Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, 2020), available at https://www.clevelandfed.org/ec202026.

82. Patricia Cohen, “This Plan Pays to Avoid Layoffs. Why Don’t More Employers Use It?” The New York Times, August 20, 2020, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/20/business/economy/jobs-work-sharing-unemployment.html.

83. Wyoming Department of Workforce Services, “Wyoming Workforce Services to implement Short-time Compensation and other new programs,” Press release, May 27, 2021, available at http://www.wyomingworkforce.org/news/2021-05-27/.

84. Thomas Lucas, Kristina Vaquera and Milena Radovic, “Virginia Renews Work Share Program to Support Virginia Employers, Employees“ (Norfolk, VA: Jackson Lewis, 2020), available at https://www.jacksonlewis.com/publication/virginia-renews-work-share-program-support-virginia-employers-employees.

85. Emily Allen, “Work-Sharing Bill For Unemployment Benefits Passes W.Va. House,” West Virginia Public Broadcasting, March 26, 2021, available at https://www.wvpublic.org/government/2021-03-26/work-sharing-bill-for-unemployment-benefits-passes-w-va-house.

Related

Explore the Equitable Growth network of experts around the country and get answers to today's most pressing questions!