Fiscal Policy and Economic Growth

Fiscal Policy and Economic Growth

J. Bradford DeLong

U.C. Berkeley

May 21, 2015

UC Center, Sacramento

What Is the Government’s Impact on Economic Growth?

- Federalism

- Global government (to the extent that such a thing exists)

- National government

- State government

- Local government

- Modes of operation

- Building capacities

- Insuring people

- Opening markets

- Regulating economic activity

- Ideologies

- Laissez-faire

- Developmental state

- Republic of virtue

- Redistribution

My Task Today: Bringing You the News

- What have we learned over the past ten years or so as we have watched governments act and react to the changing world?

- I think that we have learned—or perhaps I have learned:

- At the global/national level, government spending in general is much more beneficial than we had thought

- As long as there is a backstop bond-purchaser-of-last-resort

- At the state level, slimming down the government for the sake of slimming it down has not worked

- At the administrative level, the government appears better at structuring markets and complex administrative tasks than I had thought.

- At the local level, our restrictions on infill and density have been very, very expensive.

A Victory for “Keynesianism” of an Unexpectedly-Large Magnitude

- Blanchard and Leigh (2012)

- Small open-country multiplier of 2

- Large closed-economy multiplier of 3 or more

- Consumption spending

- Business investment

- The non-appearance of the “Confidence Fairy”

But What About Greece and Spain?

- Weisenthal (2011)

- Government bond markets can get into serious trouble when the government has no plans to pay…

- But the bulk of the Eurozone financial crisis and its negative impact on European growth stems not from feckless governments (Greece)

- It stems from fear of an unhandled panic

- Government bonds are supposed to be safe…

$1000 Bills Left on the Sidewalk: Economic and Political

Economic

- IMF (2014)

- Four considerations

- Economies still below full employment—and expected to remain so for a long time to come

- Shortage of safe assets means government bonds are uniquely valuable, hence financing costs extremely low

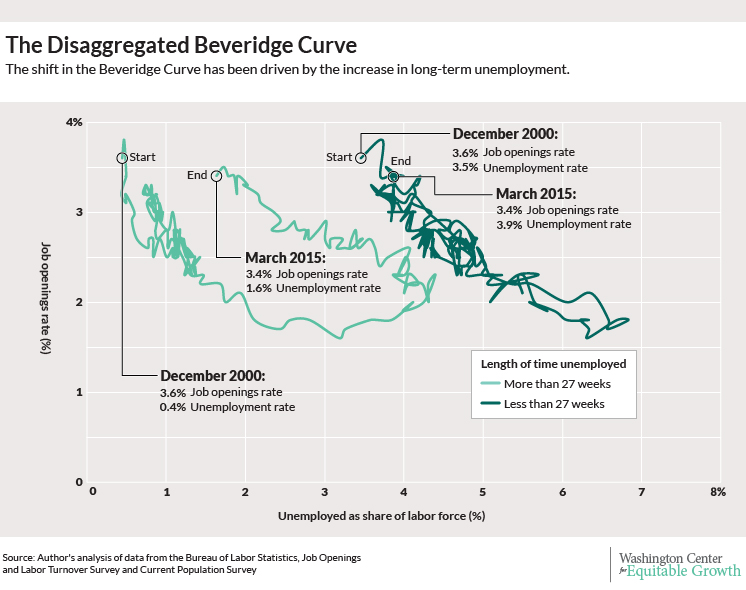

- Workers put back to work by fiscal expansion are more likely to stay attached to the labor force when full employment is again attained.

- The work done has value

- In this unusual environment, government investment in “infrastructure”—which includes public health and education—is a genuine win-win-win free lunch

- Political

- Relative U.S. performance has been very good

- Lost opportunity for Republican victory lap

News on the Low State-Tax Road to Prosperity

- The news is not good

- Governor Sam Brownback of Kansas

- Redirect entrepreneurial energy currently devoted to tax avoidance

- Make unprofitable businesses profitable

- With a Kansas population of 3 million and 1.4 million in Missouri within 40 miles of state line, steal businesses from Missouri

- No sign of any effect at all…

News on the Government’s Ability to Restructure and Open Markets

* The news is much better than I had thought

* We basically did not have much of an individual-small group health insurance market

* We had grave doubts about the attractiveness of Medicaid

* ObamaCare has only been implemented in 2/3 of the country

* Another lost opportunity for a Republican victory lap

An Area Where Government Is Not Doing so Good—Especially in California

- Hsieh and Moretti (2014)

- Cities where people can make a lot of money have, for the first time in American history, not been the cities that have grown the fastest.

- New York the biggest offender.

- San Francisco, San Jose, Riverside than numbers 2, 3, and 4

- Failures of infrastructure development

- General NIMBYism

- 10% of potential 2009 GDP left on the table

Conclusion: Economic Surprises

- Both economic and political surprises to me over the past decade…

- Economic surprises:

- The world appears significantly more “Keynesian” than I thought 10 years ago it could possibly be

- That means a bigger government—especially in investment—with more debt outstanding

- I used to think that state low-tax low-spending policies were bad for societal well-being but good for GDP—especially via job stealing. That looks much weaker

- The government has been surprisingly competent at implementing ObamaCare

- The costs of the capture of local government by anti-developmental NIMBY interests have been surprisingly large

Conclusion: Political Surprises

- The exit of the Republican Party from its historic role as the party of growth

- Used to be for efficient and low-cost government, yes

- But also for right-sized government: public investment, breaking-up of local anti-developmental lobbies, etc

- ObamaCare is RomneyCare—a Rube-Goldberged health-care reform plan with complexity arising in desire to be friendly to insurance companies and insurance markets

- The entrepreneurial rich have leveraged assets and benefit proportionally more from full employment—the successful economic policies of spending (TARP), financial guarantees, and monetary expansion (Federal Reserve) were originated by Paulson and Bernanke—both Republicans

- Yet they are not taking any victory laps…