This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth has published this week and the second is work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

A number of recent studies point toward the importance of “rents”—extra returns above and beyond what’s expected in a competitive market—and market power in the U.S. economy. The chair of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers and the former director of the Office of Management and Budget link the rise of rents to the rise in income inequality.

Whether you think the U.S. government needs more revenue to help deal with balancing the budget or to expand government programs, increasing taxes on the rich seems to be a likely answer. A look at different potential tax rates for those at the top shows that raising their taxes could generate quite a bit of revenue.

Entrepreneurship is widely praised in the United States. But policy trying to spur it isn’t well-targeted. And economists really don’t know what causes it.

Economist Arthur Okun famously asked people to consider how much money they’d be willing to lose as part of the redistribution of income. For most of the past 40 years, it was an interesting thought experiment. Now, thanks to a new paper, we can put some numbers on the amount of leakage.

Links from around the web

“There simply isn’t enough room in the limited financial pipelines flowing into new businesses, to accommodate the immense gusher of cash coming from established ones.” J.W. Mason continues his investigation into what happens to corporate funds paid out as share buybacks. [the slack wire]

The decline in the U.S. labor force participation rate since the beginning of the Great Recession has made some people question what people outside of the labor force are doing. Are they all unemployed? Josh Zumbrun digs into the data and tells us what we know about the 92 million Americans not in the labor force. [wsj]

U.S. short-term interest rates have been at zero for almost seven years now, but when the Federal Reserve starts hiking rates, they might not go up that much. Interest rates have been falling for decades now, and it’s time to get used to it, says Noah Smith. [bloomberg view]

Restaurants in America seem to be having trouble recruiting more chefs. Or at least they’re claiming they are. Like the economy at large, the answer to getting the right talent may simply require raising wages for workers, argues Shane Ferro. [huff post]

Young Americans are less likely to own homes today than previous generations were when they were young. While the housing market is recovering, the trends are ugly for both potential buyers and renters. Jordan Weissmann shows it’s hard out there for a Millennial. [slate]

Friday figure

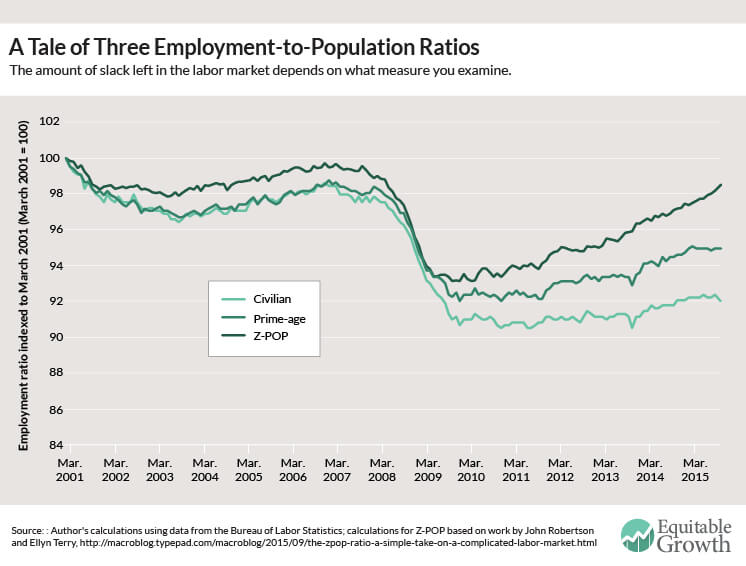

Figure from “A tale of three U.S. employment-to-population ratios” by Nick Bunker.