This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth has published this week and the second is work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

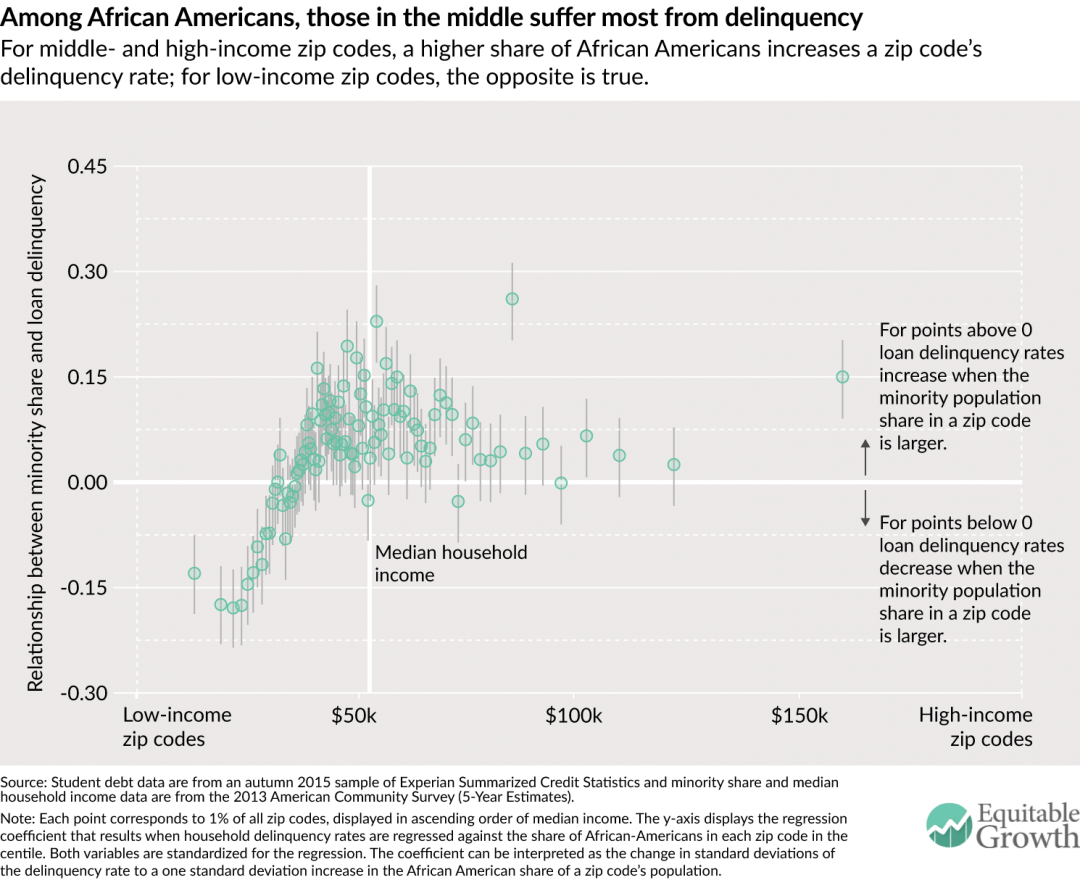

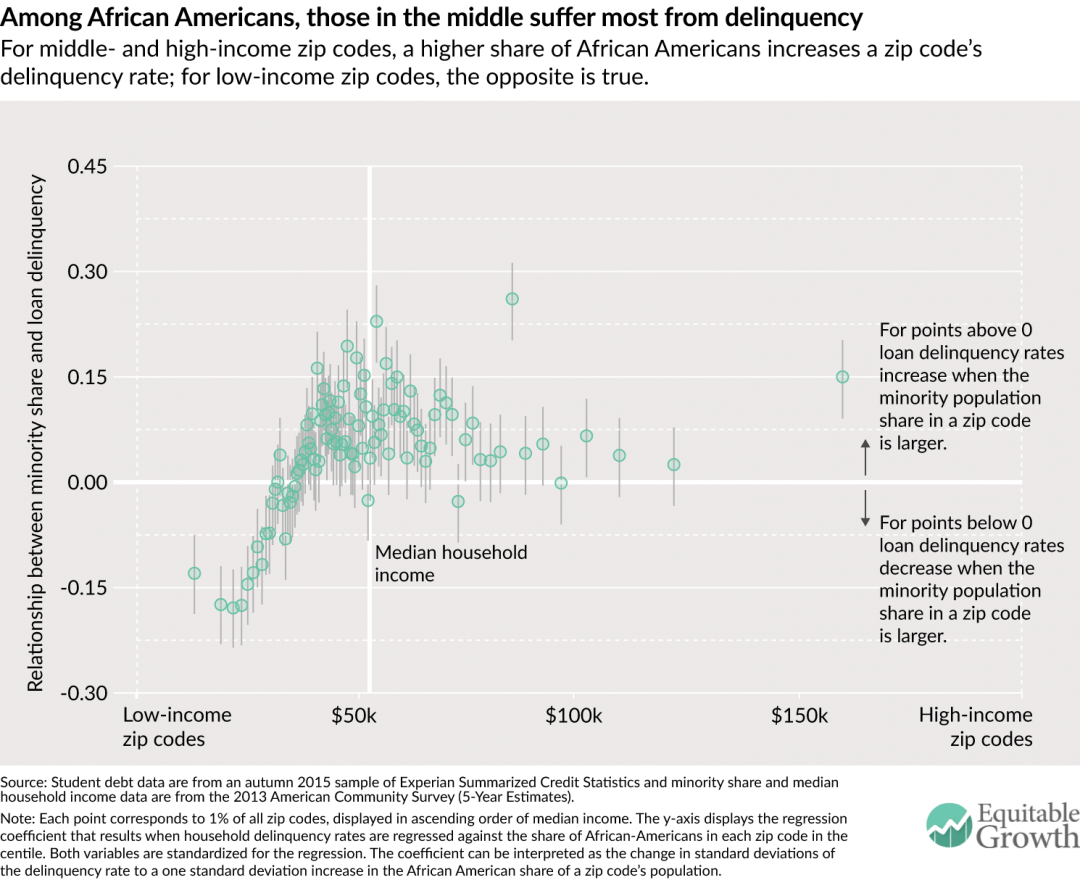

In the latest installment of our interactive Mapping Student Debt project, Marshall Steinbaum and Kavya Vaghul analyze how student loan delinquency affects African American and Latino borrowers. Not only do they find that the geography of delinquency is highly racialized, but they also point out that it’s middle-class minorities that suffer the most.

Want to dig into the link between economic inequality and innovation? If so, you’re in luck: A new report from Elisabeth Jacobs develops a framework connecting the rise in U.S. economic inequality with the nation’s decreasing levels of innovation and economic dynamism.

Millennials don’t like to hold down a job, and love to hop from one job to another—or so the story goes. As Nick Bunker explains, though, research shows that young workers today are actually less likely to jump from job to job than in the past. What’s more, the increase in job switching has actually been strongest for older workers.

U.S. productivity growth has slowed since 2004, and some economists and analysts are wondering if our productivity statistics are accurately capturing the gains from new technology. In short, the rise of “free” services that enhance productivity (like Google, for example) may understate the output growth of the U.S. economy and therefore our productivity growth. But looking at an analysis by economist Chad Syverson of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, Nick Bunker tells us why the mismeasurement story actually doesn’t add up.

When looking at the relationship between productivity growth and wages, economists often view it in the sense that productivity determines wages. But Nick Bunker highlights a few arguments making the case that boosting wages may also increase the pace of productivity growth.

Links from around the web

Seven years ago this week, Congress passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act to help the United States recover from the Great Recession. Jared Bernstein and Ben Spielberg highlight a few lessons we should learn from the Recovery Act in order to help us prepare for the next recession. [wa post]

Last month, the Bank of Japan set its interest rate at negative 0.1 percent—joining the central banks of Denmark, Sweden, and Switzerland, which have also moved their interest rates below zero. Frances Coppola argues, however, that negative interest rates are actually a very bad idea. [coppola comment]

Looking at this year’s U.S. presidential election, Noah Smith notes that the United States is seemingly out of good ideas for spurring economic growth. With that said, Smith highlights the promise of an idea that he tentatively calls “New Industrialism”—an idea to “reform the financial system and government policy to boost business investment.” [bloomberg view]

According to a new study from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, there’s an interesting downside to winning the lottery: Your neighbors may end up in financial ruin trying to keep up with you. But as Shane Ferro explains, this study “takes income inequality to its extreme conclusion and asks what happens to people who get left behind.” And as the divide between rich and poor continues to grow in our economy, it’s worth looking at how that affects all of us. [huff po]

With the ongoing downturn in commodity prices, many economists and analysts worry that sovereign wealth funds (government-owned investment funds) will sell off assets and, in turn, destabilize markets. Martin Sandbu argues, however, that in the long run, sovereign wealth funds should actually be “seen as a force for good—and be used as such much more than they have been.” [financial times]

Friday figure

Figure from “How the student debt crisis affects African Americans and Latinos” by Marshall Steinbaum and Kavya Vaghul.