- : “I spent literally years making fun of righty econ bloggers for saying there are “Keynesians” out there who think multipliers are always big.”

- (1960): The Problem of Social Cost

- (1937): The Nature of the Firm

- : Why Canada should foster a ‘second-chance’ society

- : IMF calls on G20 to take ‘bold’ action

- : Carbon inequities, climate change, and complementary solutions

- : What explains the rise in income inequality at the top of the income distribution?

- : How the student debt crisis affects African Americans and Latinos

- : Equitable Growth in Conversation

Must-read: Thomas Piketty: “A New Deal for Europe”

Must-Read: : A New Deal for Europe: “Only a genuine social and democratic refounding of the eurozone…

…designed to encourage growth and employment, arrayed around a small core of countries willing to lead by example and develop their own new political institutions, will be sufficient to counter the hateful nationalistic impulses that now threaten all Europe. Last summer, in the aftermath of the Greek fiasco, French President François Hollande had begun to revive on his own initiative the idea of a new parliament for the eurozone. Now France must present a specific proposal for such a parliament to its leading partners and reach a compromise. Otherwise the agenda is going to be monopolized by the countries that have opted for national isolationism—the United Kingdom and Poland among them…

Must-read: David Glasner (2015): “Neo-Fisherism and All That”

Must-Read: (2015): Neo-Fisherism and All That: “John Cochrane and Stephen Williamson [believe]… if the central bank wants 2% inflation… [and] if the Fisherian real rate is 2%…

…the central bank should set its interest-rate instrument (Fed Funds rate) at 4%, because, in equilibrium–and, under rational expectations, that is the only policy-relevant solution of the model–inflation expectations must satisfy the Fisher equation. The Neo-Fisherians believe… they have overturned at least two centuries of standard monetary theory… back… to Henry Thornton…. The way to reduce inflation is for the monetary authority to reduce the setting on its interest-rate instrument and the way to counter deflation is to raise the setting on the instrument…. Unwilling to junk more than 200 years of received doctrine on the basis, not of a behavioral relationship, but a reduced-form equilibrium condition containing no information about the direction of causality, few monetary economists and no policy makers have become devotees of the Neo-Fisherian Revolution….

Let Cochrane read Nick Rowe…. If he did, he might realize that if you do no more than compare alternative steady-state equilibria, ignoring the path leading from one equilibrium to the other, you miss just about everything that makes macroeconomics worth studying…. The very notion that you don’t have to worry about the path by which you get from one equilibrium to another is so bizarre that it would be merely laughable if it were not so dangerous…

Must-read: Tim Duy: “Lacker, Kaplan, Fischer”

Must-Read: The list of features of the current macroeconomic situation that the Federal Reserve’s communications strategy suggests that it does not grasp keeps growing. In the past we had:

- The asymmetry of the loss function for undershooting vis-a-vis overshooting nominal GDP growth.

- The weakness of monetary policy tools as stimulus in and near the liquidity trap vis-a-vis the strength of monetary policy tools to cool off the economy always.

- The extraordinarily low precision of estimates of the Phillips Curve.

And now we have also:

- The degree to which the slope of the Phillips Curve now is smaller than it was in the 1970s.

- The degree to which the gearing between increases in inflation now and increases in future expected inflation has decreased since the 1970s.

- The fact that lack of strong association between financial jitters and subsequent reduced growth is a reduced form that factors in a stimulative monetary response in response to such jitters.

- The strong links between credit-channel disruptions and reduced spending growth.

And, above all, the fact that in the Greenspan and Volcker eras a lack of concern for downside risks was excusable because demand could always be swiftly and substantially boosted in an afternoon via large interest-rate reductions. Not so in the Bernanke-Yellen era.

It thus seems more and more to me as though the Federal Reserve is making macroeconomic policy in a world that simply does not exist. Tim Duy has comments:

: Lacker, Kaplan, Fischer: “Today Richmond Federal Reserve President Jeffrey Lacker argued that the case for rate hikes remains intact…

…On the opposite side of the table sits Dallas Federal Reserve President Robert Kaplan… very dovish…. Pure wait-and-see, risk management mode…. Federal Reserve Vice Chair Stanley Fischer remains less-moved by recent developments. Instead, low unemployment rates capture his attention…. Fischer sounds very uncomfortable with the prospect of the unemployment rate falling much below 4.7%. He is getting an itchy trigger finger.

I remain unmoved by this logic….

We have seen similar periods of volatility in recent years–including in the second half of 2011–that have left little visible imprint on the economy…. As Chair Yellen said in her testimony to the Congress two weeks ago, while ‘global financial developments could produce a slowing in the economy, I think we want to be careful not to jump to a premature conclusion about what is in store for the U.S. economy.’

This echoes the comments of… John Williams, and again misses the Fed’s response to financial turmoil. In 2011, it was Operation Twist…. I really do not understand how Fed officials can continue to dismiss market turmoil using comparisons to past episodes when those episodes triggered a monetary policy response. They don’t quite seem to understand the endogeneity in the system.

My sense is that there remains a nontrivial contingent within the Fed that really, truly believes they need to hike sooner than later for fear that overshooting the employment mandate will result in overshooting the inflation target. This contingent is attempting to look at the financial system as separate from the ‘real’ economy. That will not work. No matter how good the underlying fundamentals, if you let the financial system implode, it will take the economy down with it. I don’t know that the Fed needs to cut rates, or that they needed to cut rates as deeply as they did during the Asian Financial crisis, but I do know this: The monetary authority should not tighten into financial turmoil. Wait until you are out of the woods. That’s Central Banking 101…

Carbon inequities, climate change, and complementary solutions

Today, the earth’s atmosphere holds more than 400 parts per million of carbon dioxide. That’s roughly 40 percent more than carbon dioxide levels at the start of the Industrial Revolution, and it’s primarily due to our unruly combustion of fossil fuels. Considering that carbon dioxide emissions increase greenhouse gas levels and consequently exacerbate climate change, environmentalists in the United States have long been proposing a Pigovian tax on the carbon contents of goods and services.

But how does any of this relate to equity? Let’s backtrack.

It begins with the fact that the rich are one of the biggest agents of climate change. In a study released in 2005, the U.S. Census Bureau found that high-income households (those earning more than $75,000 a year) consume double the energy of the poorest households (those earning less than $10,000 a year) in the United States. As a result, the rich significantly contribute to carbon dioxide emissions, too. A recent report from Oxfam concluded that people in the top tenth of the world’s income distribution are to blame for 50 percent of global emissions, while those in the bottom half of the distribution account for only 10 percent of emissions.

What makes carbon inequality worse is that minorities and low-income communities are disproportionately harmed by climate change’s pernicious effects. The White House’s National Climate Assessment report found that these vulnerable groups in the United States are disparately buffeted by the onset of heat waves, worsening air quality, and extreme weather events, which has ramifications for physical and mental health and financial well-being.

By nature, the causes and consequences of climate change have distributional components. And so does a tax-based solution—well, in part.

In principle, a carbon tax is a fee that is placed on the carbon contents of different types of fossil fuels based on the amount of carbon dioxide each type of fuel emits when it is used, factoring in the long-term social costs of emissions as well. Coal—in comparison to oil and natural gas, for example—emits the most carbon dioxide per unit of energy, so it would likely have the highest tax rate. There are also several questions about how the tax would be implemented and who should be taxed: Should the energy producers (upstream), distributors and retailers (midstream), or the consumers (downstream) be the point of taxation? Regardless of who in the chain pays, the tax is the most efficient way to discourage high-carbon consumption behavior to ultimately reduce emissions.

The problem, however, is that a carbon tax may also increase the price of products like gasoline, utilities, and even food, which is what makes it regressive. Statistics show that poor families generally spend a higher portion of their incomes on these basic necessities compared to middle-class and rich households. So, if the prices on products increase, poor families will be hit the hardest. In fact, a 2009 study by environmental economists Corbett Grainger of the University of Wisconsin and Charles Kolstad of Stanford University documents the distributional effects of a hypothetical $15-per-ton tax. They find that the burden of a carbon tax on households at the bottom fifth of the income distribution would be at least 1.4 times to 4 times higher than for households at the top fifth. What’s more, Grainger and Kolstad note that if a tax is also applied to other types of greenhouse gases, this disproportionate burden would only increase.

Of course, there are a couple ways to soften a carbon tax’s potential impact on low-income families. One extremely efficient idea is to recycle the revenues from a carbon tax to cut another tax. This “tax swap” could work by providing tax credits to reduce the regressive burden of corporate income tax (capital recycling) or payroll income tax (payroll recycling). The second idea is to redistribute the revenues from a carbon tax through lump-sum rebates. Economist Chad Stone at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities argues that these rebates could theoretically reach low-income households through refundable tax credits, a supplement to direct federal payments to eligible groups, or the electronic benefit transfer (EBT) system.

It’s easy to imagine that Congress might disagree on how to make a carbon tax more progressive or what to do with the revenues, which could prolong passing new or existing proposals. And, as it stands, carbon taxes might not fix resource inequalities at their root. The fact that low-income families spend a disproportionate amount of their income on carbon-rich essentials and don’t nearly contribute as much to emissions as the rich is still a signal that we must also think about other innovative ways to reduce energy costs for families while keeping carbon emissions down.

Given congressional gridlock, cities have been exploring ways to promote carbon equity. Improving the transit infrastructure and walkability of metro regions is certainly one option, especially because transportation and gasoline costs comprise the second-largest investment for low-income families and passenger cars account for more than 30 percent of transportation-related greenhouse gas emissions. In practice, these improvements could include planning strategies such as mixed-income transit-oriented development with mixed-use neighborhood design. Simply, this could help contain sprawl and reduce motor vehicle reliance, consequently reducing fuel consumption and carbon emissions for families across the income distribution.

Another community-based strategy is to adopt district energy systems. District energy is a highly efficient heating and cooling system that uses a central plant in typically a village- or neighborhood-sized part of a city to distribute energy to and from buildings within the district. Because the system is localized, it is able to balance energy demand between properties on the grid. Having a central plant also allows for integration of other renewable energy sources such as geothermal loops and solar cells. It is a significant investment upfront, but it boasts impressively lower carbon dioxide emissions than traditional systems while trimming home energy bills.

All this said, there are still several questions about the feasibility, costs, implementation timelines, and even carbon emissions abatement of these city-centric programs, especially in comparison to the efficiency of a carbon tax. That’s why, in the meantime, pursuing multiple, complementary solutions simultaneously can be the most effective approach to slowing climate change and dealing with its repercussions.

Whether we approach carbon use and emissions and climate change from the federal, state, or local levels, though, one thing is clear: Conversations about our environment, just like conversations about our economy, must include a vision to augment equity.

What explains the rise in income inequality at the top of the income distribution?

Skill-biased technological change is a prominent explanation for the rise in income inequality over the past few decades, but it is not clear how this theory can explain the differential rise in very top incomes across countries. The theory, argued by Harvard’s Lawrence Katz and the University of Chicago’s Kevin Murphy and recently overhauled by MIT’s Daron Acemoglu and David Autor, states that changes in technology drive increased demand for workers whose skills best complement new production processes. But as Ian Dew-Becker and Robert Gordon explain, “it is difficult to think of what particular skill set would account for the meteoric rise of incomes in the top 1 and 0.1 percentiles.”

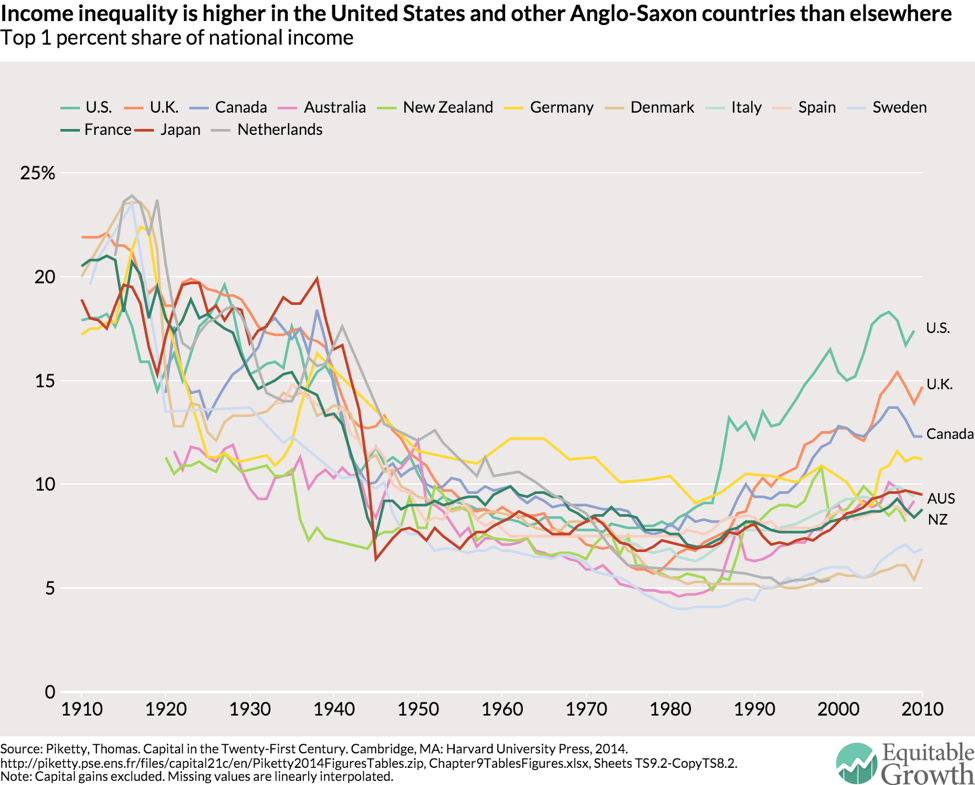

A purely technological explanation cannot explain all of the variance in the change in top incomes across rich countries. Figure 1 shows the share of national income accruing to the top 1 percent of earners (excluding capital gains) over time for a selection of highly developed countries, from Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

Figure 1

The chart provides a history lesson in its own right. You can see the sky-high inequality of the early 1900s, the remarkable collapse in top incomes following World War II, and the long moderation of income inequality during a period of high growth in the succeeding three decades. After that, we can see the recent explosion in top-end inequality starting during the mid-1980s.

Notably, the pace of growth in that inequality is strikingly different among developed countries. Anglo-Saxon countries, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada, saw their rich run away from the rest of their populations. In the United States, the top 1 percent of earners went from claiming 8 percent of national income in 1980 to nearly 18 percent of national income in 2010. The United Kingdom saw a similar increase over the same time period (from 6 percent to 15 percent), as did Canada (from 8 percent to 12 percent).

These gains contrast sharply with much more modest changes in other countries over that time period:

- France: 8 percent to 9 percent

- Germany: 10 percent to 11 percent

- Spain: 8 percent to 9 percent

- Italy: 7 percent to 9 percent

- Sweden: 4 percent to 7 percent

Given this new understanding of top-end incomes, can we point to some additional explanations? While some countries do have some technological advantages over others, all advanced Western economies are broadly on the same level in terms of development. Modern information technology is pervasive in all major sectors of the economy, and they all have high-performing education systems. So why is similar tech driving dissimilar returns to skill across the developed world? Are the United States and the United Kingdom exceptional in how talented their high performers are? Or is it a matter of institutional disparities between countries—that is, the degrees to which collective bargaining, high marginal income tax rates, and intellectual property regimes rein in the bargaining power of the top 1 percent?

These are still open questions, and it’s beyond the scope of this blog post to give a full answer. Suffice it to say, although inequality is increasing in many rich countries, the severity to which it’s increasing varies dramatically depending on where you look.

Puzzled by Gerry Friedman…

A question about the estimable Gerry Friedman:

How can an increase in government spending of $1.4 trillion/year generate a $14 trillion increase in spending in the year 2026? But it really looks to me like he has both:

- the very dubious assumption that all 10%-points of the shortfall from the trend as of 2007 can be made up relatively easily’, and

- a multiplier of not the 3-in-and-near-a-liquidity trap I carry around in the back of my head, but 10.

But Friedman’s text claims his multiplier is not even 3, but less than 2, and averaging roughly 1…

In short: In his runs Friedman has government spending higher in 2026 by $1.4 trillion than in baseline. He has real GDP higher in 2026 by $14 trillion. What other components of real spending are higher by how much in order to make that real GDP number in the year 2016 higher than baseline by $14 trillion? And what mechanisms are making those components higher?

It’s fine to propose aspirational policies based on a hope that the world is such that things will break your way. It’s not so good to put the world breaking your way forward as a central-case forecast of what your policies will do. And it’s distressing that I cannot figure out how to make Friedman’s analysis hold together quantitatively even if I do allow the assumption that the entire output relative to the pre-2007 potential-output trend can be closed easily…

Must-reads: February 22, 2016

- : A College Degree Is Worth (Disproportionately) Less If You Are Raised Poor

- : Abundance and the Direction of Technological Growth

- : Your Landlord Is a Drag on Growth

- : Ronnie O’Sullivan & the Limits of Incentives

- : Takahashi Korekiyo and Fiscal Stimulus in Japan in the 1930s

- : Central bankers on the defensive as weird policy becomes even weirder

- The Ghost of Takahashi Haunts Abenomics

- : Draghi Wants the Cake, and Eat It

- : Improving Conventional Unconventional Policy

- : Schooling and Balanced Growth

- : The Habakkuk Hypothesis

- : Technological Unemployment

- : The Most Important Apple Executive You’ve Never Heard Of

Weekend reading: H.G. Wells: On Becoming a Socialist

(1908): Becoming a Socialist: from “New Worlds for Old” (London: Macmillan), pp. 16-19: “A walk I had a little while ago with a friend along the Thames Embankment…

<

blockquote>

…from Blackfriars Bridge to Westminster. We had dined together and we went there because we thought that with a fitful moon and clouds adrift, on a night when the air was a crystal air that gladdened and brightened, that crescent of great buildings and steely, soft-hurrying water must needs be altogether beautiful.

And indeed it was beautiful: the mysteries and mounting masses of the buildings to the right of us, the blurs of this coloured light or that, blue-white, green-white, amber or warmer orange, the rich black archings of Waterloo Bridge, the rippled lights upon the silent flowing river, the lattice of girders, and the shifting trains of Charing Cross Bridge–their funnels pouring a sort of hot-edged moonlight by way of smoke–and then the sweeping line of lamps, the accelerated run and diminuendo of the Embankment lamps as one came into sight of Westminster.

The big hotels were very fine, huge swelling shapes of dun dark-gray and brown, huge shapes seamed and bursting and fenestrated with illumination, tattered at a thousand windows with light and the indistinct glowing suggestions of feasting and pleasure. And dim and faint above it all and very remote was the moon’s dead wan face veiled and then displayed.

But we were dashed by an unanticipated refrain to this succession of magnificent things, and we did not cry, as we had meant to cry:

How good it was to be alive!

Along the embankment, you see, there are iron seats at regular intervals, seats you cannot lie upon because iron arm-rests prevent that, and each seat, one saw by the lamplight, was filled with crouching and drooping figures. Not a vacant place remained, not one vacant place.

These were the homeless, and they had come to sleep here. Now one noted a poor old woman with a shameful battered straw hat awry over her drowsing face, now a young clerk staring before him at despair; now a filthy tramp, and now a bearded, frock-coated, collarless respectability; I remember particularly one ghastly long white neck and white face that lopped backward, choked in some nightmare, awakened, clutched with a bony hand at the bony throat, and sat up and stared angrily as we passed. The wind had a keen edge that night, even for us who had dined and were well-clad. One crumpled figure coughed and went on coughing–damnably.

‘It’s fine,’ said I, trying to keep hold of the effects to which this line of poor wretches was but the selvage; ‘it’s fine! But I can’t stand this.’

‘It changes all that we expected,’ admitted my friend, after a silence.

‘Must we go on–past them all?’

‘Yes. I think we ought to do that. It’s a lesson perhaps–for trying to get too much beauty out of life as it is, and forgetting. Don’t shirk it!’

‘Great God!’ cried I. ‘But must life always be like this? I could die, indeed, I would willingly jump into this cold and muddy river now, if by so doing I could stick a stiff dead hand through all these things in the future,–a dead commanding hand insisting with a silent irresistible gesture that this waste and failure of life should cease, and cease forever.’

‘But it does cease! Each year in its proportions it is a little less.’

I walked in silence, and my companion talked by my side.

‘We go on. Here is a good thing done, and there is a good thing done. The Good Will in man–‘

‘Not fast enough. It goes so slowly–and in a little while we too must die.’

‘It can be done,’ said my companion.

‘It could be avoided,’ say I.

‘It shall be in the days to come. There is food enough for all, shelter for all, wealth enough for all. Men need only know it and will it. And yet we have this!’

‘And so much like this!’ said I.

So we talked and were tormented.

And I remember how later we found ourselves on Westminster Bridge, looking back upon the long sweep of wrinkled black water that reflected lights and palaces and the flitting glow of steamboats, and by that time we had talked ourselves past our despair. We perceived that what w

Ed Luce says some very nice things about Steve Cohen’s and my forthcoming “Concrete Economics”

It is very nice to get a favorable view that indicates that the book we wrote is–at least in some respects–the book we thought we had written and tried to write. So Steve and I find ourselves especially grateful this weekend to the very-sharp Ed Luce:

: Is robust American Growth a Thing of the Past?: “My hunch is that [Robert] Gordon is a little too adamant…

…Perhaps we will come up with a cure to Alzheimer’s disease… androids will take… all the low-paying jobs. But even if he is right, there are things we can do…. The embittered US presidential primary battle offers a case study of what happens to politics when people’s economic hopes are dashed…. For an antidote to Gordon’s fatalism, turn to Concrete Economics.

This short book, by the economists Stephen Cohen and Bradford DeLong, is light on data and high on readability. What it shares with Gordon is the view that today’s economy is not serving most Americans well. Growth has slowed and inequality has risen.

Unlike Gordon, however, Cohen and DeLong believe that Americans have the power to do something about it. The key lies in better understanding their history.

If you ask Americans to identify the elixir of their country’s success, most would say something about freedom and entrepreneurship. Government would not feature. Their answer, in other words, would be ideological. A more accurate response, in the authors’ view, would be to draw on America’s creed of pragmatism. Franklin Roosevelt called it ‘bold, persistent experimentation’. Alexander Hamilton — perhaps the most modern of the founding fathers, and the only one who has a rap musical about him running on Broadway — developed the ‘American system’. Cohen and DeLong make a plea for Americans to abandon the ‘ideological incantations and abstract obfuscations’ that have held since the late 1970s in favour of ‘whatever works’ economics.

They make a persuasive case. From Hamilton’s infant industries to Abraham Lincoln’s Homestead Act, the federal government played a guiding role in the American success:

The invisible hand was repeatedly lifted at the elbow by the government and replaced in a new position where it could go on to perform its magic,

they write. If Lincoln had auctioned off land in the west to the highest bidders rather than parceled it out to families, the US would have developed along Latin American-style lines. Government was behind many of the technological leaps that Gordon writes about. Even in the ideological era, government has prodded the market to go where it decrees. But it has taken wrong turns. Huge chunks of the US economy are devoted to financial trading, healthcare claims processing, real estate transaction and other ‘busy but useless’ activity.

It is within America’s scope to reclaim its pragmatism, say the authors. Theirs is a lyrical manifesto. It is a million miles from Gordon’s techno-determinism and a different universe to Trump’s vision. It is also a corrective. Read Gordon and weep. Then perk yourself up with Concrete Economics. Some things are beyond our power to foresee. Others are within the realm of the possible.

Figure 5% of GDP wasted in excess health-care administration, 5% wasted in excess earnings paid to finance, another 15% wasted–from the perspective of America’s societal well-being–in incentivizing the rich and the super-rich in ways that are either ineffective or counterproductive, and another 5% subtracted from GDP by an ideological refusal to do win-win policies (cough infrastructure; cough aggregate demand; plus others) easily within our graph–and we have an America that could be 30% richer, not in the sense that measured real GDP would by 30% higher but in the sense that we would be delivering 30% more useful goods and services to those for whom it really counts. That would hold off Gordon’s stagnation for nearly a generation. And we could do that. Relatively easily. With our ideological blinders off. And with our political will on.