Typically smart thoughts by Paul Krugman on carbon pricing:

Paul Krugman: 101 Boosteris: “I see that @drvox is writing a big piece on carbon pricing…

…I don’t want to step on his forthcoming message, but what he’s said so far helped crystallize something I’ve meant to write about… ‘101 boosterism’… a takeoff on Noah Smith’s clever writing about ‘101ism’, in which economics writers present Econ 101 stuff about supply, demand, and how great markets are as gospel, ignoring the many ways in which economists have learned to qualify those conclusions in the face of market imperfections. His point is that while Econ 101 can be a very useful guide, it is sometimes (often) misleading…. My point is… even when Econ 101 is right, that doesn’t always mean that it’s… the most important thing…. Economists… delight in talking about issues where 101 refutes naïve intuition, but that doesn’t… mean… these are the crucial policy issues….

In my original home field of international trade. Comparative advantage says that countries are made richer by international trade, even if one trading partner is more productive than the other across the board, and the less productive country can only export thanks to low wages. Paul Samuelson once declared this the prime example of an economic insight that is true without being obvious–and to this day you get furious attempts to refute the concept…. [But] there are a variety of reasons why, despite this big insight, free trade may not be the right policy–that’s Noah’s 101ism. But… even if comparative advantage is a profound insight, does this make free trade versus protectionism a front-burner issue?…. The answer… from standard trade models… is, not as important as many people seem to think…. If you want enormous benefits to trade, you have to invoke things like technology transfer that aren’t in the very analysis that gives the case for free trade such prestige….

There’s a kind of bait and switch, in which people invoke Ricardo and the gains from trade to say “free trade good”, then tell scare stories… [which have] nothing to do with the classical analysis of the gains from trade.

It seems to me that there’s something similar involved in discussions of carbon pricing…. How important is it that our carbon-emissions strategy take the form of a universal or near-universal price on carbon? The answer… is that it depends on the complexity of the required response. If reducing emissions really has to involve moving on many fronts, anything that looks like an administrative solution… is going to be much more costly than carbon pricing that exploits all the possibilities. But if a large part of the solution is going to involve… putting a quick end to the practice of burning coal… getting to broad-based carbon pricing is much less central…. Just because Econ 101 makes a smart, counterintuitive point doesn’t make that point of central importance…. People should know what’s in the textbook…. But never imagine that it’s the be-all and end-all…

And–perhaps, perhaps not–this:

There’s a kind of bait and switch, in which people invoke Ricardo and the gains from trade to say “free trade good”, then tell scare stories… [which have] nothing to do with the classical analysis of the gains from trade…

is a deserved criticism and smackdown of me here on March 12:

The Benefits of Free Trade: Time to Fly My Neoliberal Freak Flag High!: So I guess it is time to say ‘I think Paul Krugman is wrong here!’ and fly my neoliberal freak flag high…

On the analytics, the standard HOV models do indeed produce gains from trade by sorting production in countries to the industries in which they have comparative advantages. That leads to very large shifts in incomes toward those who owned the factors of production used intensively in the industries of comparative advantage: Big winners and big losers within a nation, with relatively small net gains.

But the map is not the territory. The model is not the reality. An older increasing-returns tradition sees productivity depend on the division of labor, the division of labor depends on the extent of the market, and free-trade greatly widens the market. Such factors can plausibly quadruple The Knick gains from trade over those from HOV models alone, and so create many more winners.

Moreover, looking around the world we see a world in which income differentials across high civilizations were twofold three centuries ago and are tenfold today. The biggest factor in global economics behind the some twentyfold or more explosion of Global North productivity over the past three centuries has been the failure of the rest of the globe to keep pace with the Global North. And what are the best ways to diffuse Global North technology to the rest of the world? Free trade: both to maximize economic contact and opportunities for learning and imitation, and to make possible the export-led growth and industrialization strategy that is the royal and indeed the only reliable road to anything like convergence.

So I figure that, all in all, not 5% but more like 30% of net global prosperity–and considerable reduction in cross-national inequality–is due to globalization. That is a very big number indeed. But, remember, even the 5% number cited by Krugman is a big deal: $4 trillion a year, and perhaps $130 trillion in present value.

As for the TPP, the real trade liberalization parts are small net goods. The economic question is whether the dispute-resolution and intellectual-property protection pieces are net goods. And on that issue I am agnostic leaning negative. The political question is: Since this is a Republican priority, why is Obama supporting it without requiring Republican support for a sensible Democratic priority as a quid pro quo?

That said, let me wholeheartedly endorse what Paul (and Mark) say here:

as Mark Kleiman sagely observes, the conventional case for trade liberalization relies on the assertion that the government could redistribute income to ensure that everyone wins—but we now have an ideology utterly opposed to such redistribution in full control of one party…. So the elite case for ever-freer trade is largely a scam, which voters probably sense even if they don’t know exactly what form it’s taking….

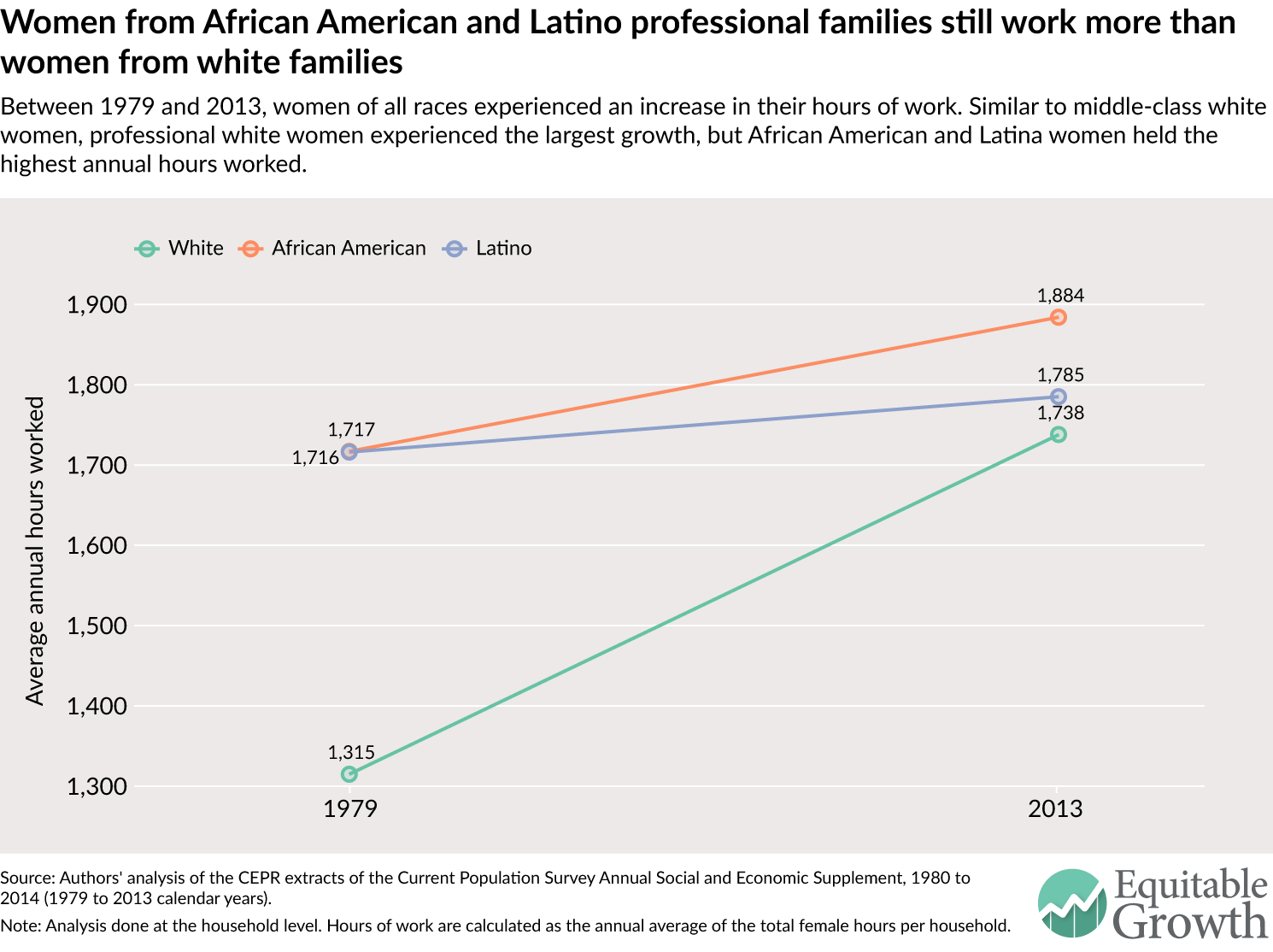

Figure from “

Figure from “