This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth has published this week and the second is work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Central banks have long been in the business of buying bonds to fight economic downturns. But what if they bought stocks? This fairly radical idea is suggested by the economic research of Roger Farmer.

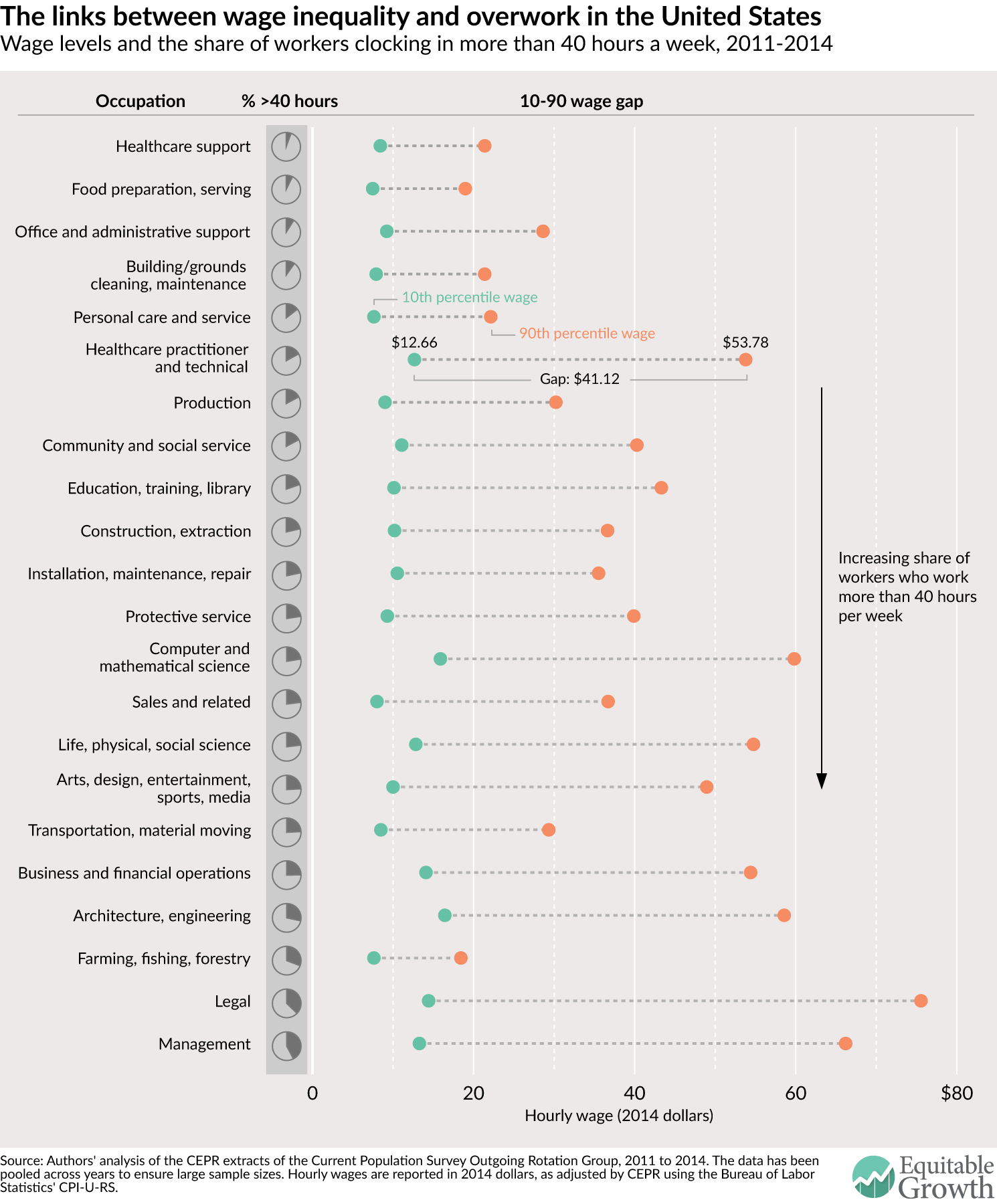

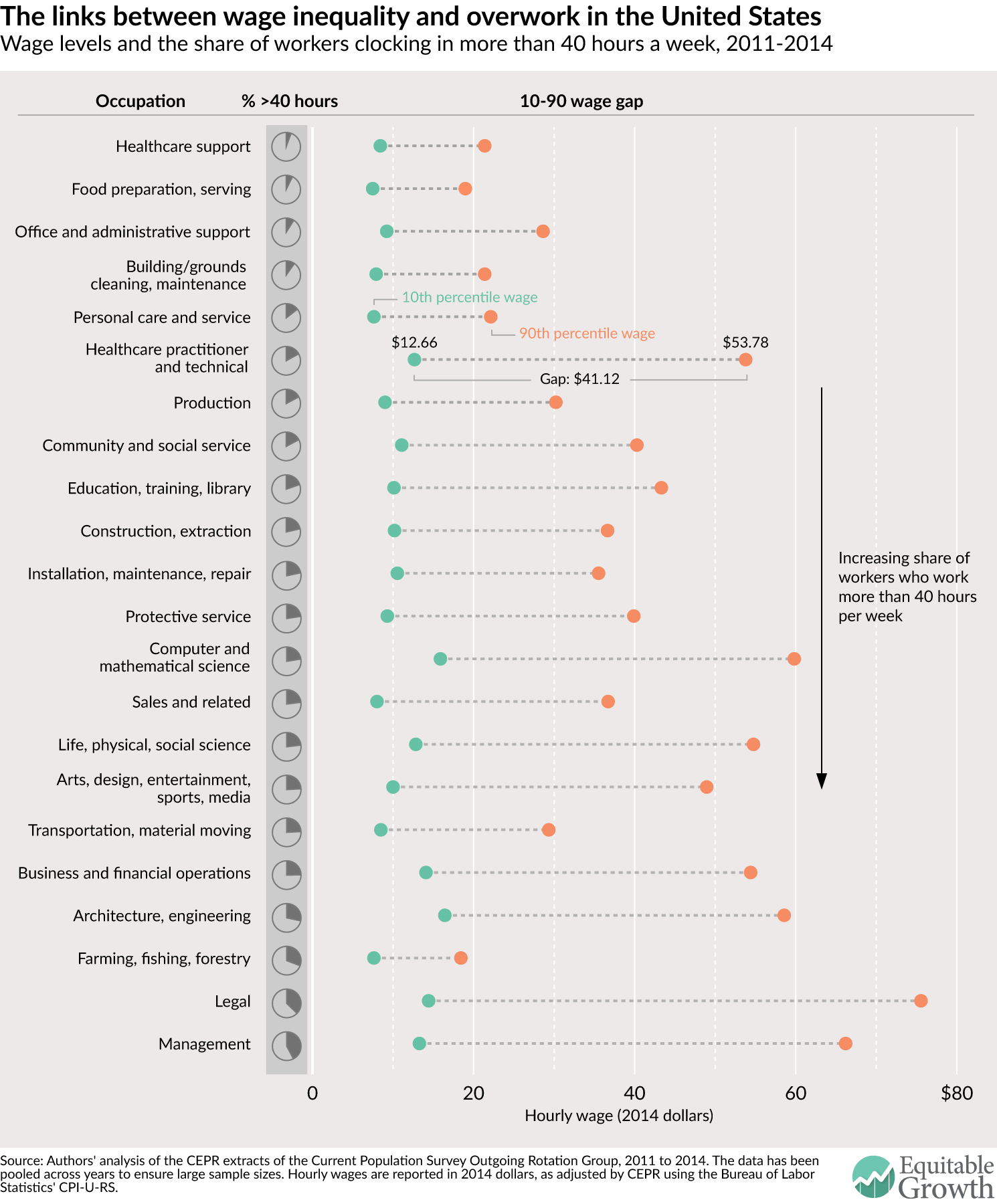

Long hours are sometimes seen as the sign of hard work and a job well done. But that’s not necessarily true. In a new report, Heather Boushey and Bridget Ansel look into the effects of long work hours on economic growth and inequality.

A new rule concerning equity crowdfunding was designed in the hope of boosting entrepreneurship and possibly letting someone besides institutional investors and the rich get access to the high-growth investments. The final rule announced this week seems unlikely to do either.

Speaking of final rules, the Department of Labor finalized its rule concerning overtime work, raising the threshold for eligible salaried workers to just over $47,000, significantly increasing the amount of workers covered. Bridget Ansel argues the new rule is good economics and good business.

As income has flowed more and more to the households at the top of the income ladder, it makes sense that companies would target where the money is going. A new working paper argues that the higher levels of income inequality has affected where product innovation is happening.

Links from around the web

One economic trend is like the weather: “everybody complains about productivity growth but nobody does anything about it.” Jared Bernstein asks a number of economists, included Equitable Growth’s Heather Boushey, about ideas to actually do something about productivity growth. [on the economy]

“GDP is a useful but limited measure. The problem is not with GDP, but with people who might see it as a comprehensive measure of well-being. It isn’t.” Dean Baker argues against including environmental or equity concerns in our common measure of economic output. [beat the press]

More and more attention is being paid to concerns about competition in the economy and the role of antitrust policy. Izabella Kaminska wonders if monopolism isn’t on the rise because all business strategies are now focused on claiming the monopolist throne for themselves. [ft alphaville]

The U.S. economy, at least measured in terms of the speed of output growth, may have had its best days in its past. Potential economic growth seems to be approaching outright stagnation and, as Eduardo Porter points out, policy needs to do something to help boost growth. [nyt]

Policymakers also have a problem in the short-term when it comes to economic growth. Members of the Federal Reserve’s policymaking committee have been giving signs they may raise interest rates again soon. Ryan Avent argues such a move would an incautious mistake. [free exchange]

Friday figure

Figure from “Overworked America” by Heather Boushey and Bridget Ansel