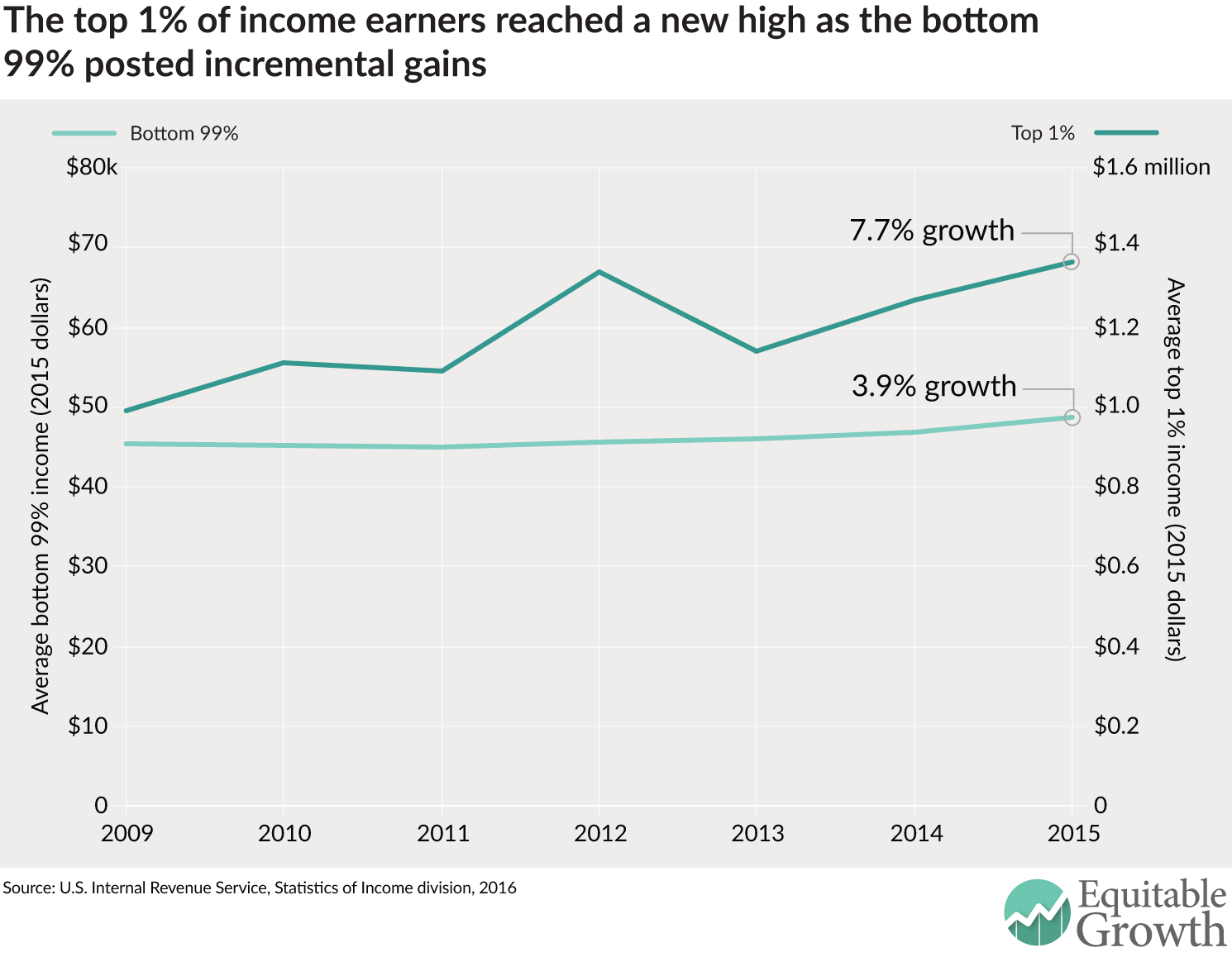

The top 1 percent income earners in the United States hit a new high last year, according to the latest data from the U.S. Internal Revenue Service. The bottom 99 percent of income earners registered the best real income growth (after factoring in inflation) in 17 years, but the top one percent did even better. The latest IRS data show that incomes for the bottom 99 percent of families grew by 3.9 percent over 2014 levels, the best annual growth rate since 1998, but incomes for those families in the top 1 percent of earners grew even faster, by 7.7 percent, over the same period. (See Figure 1.)

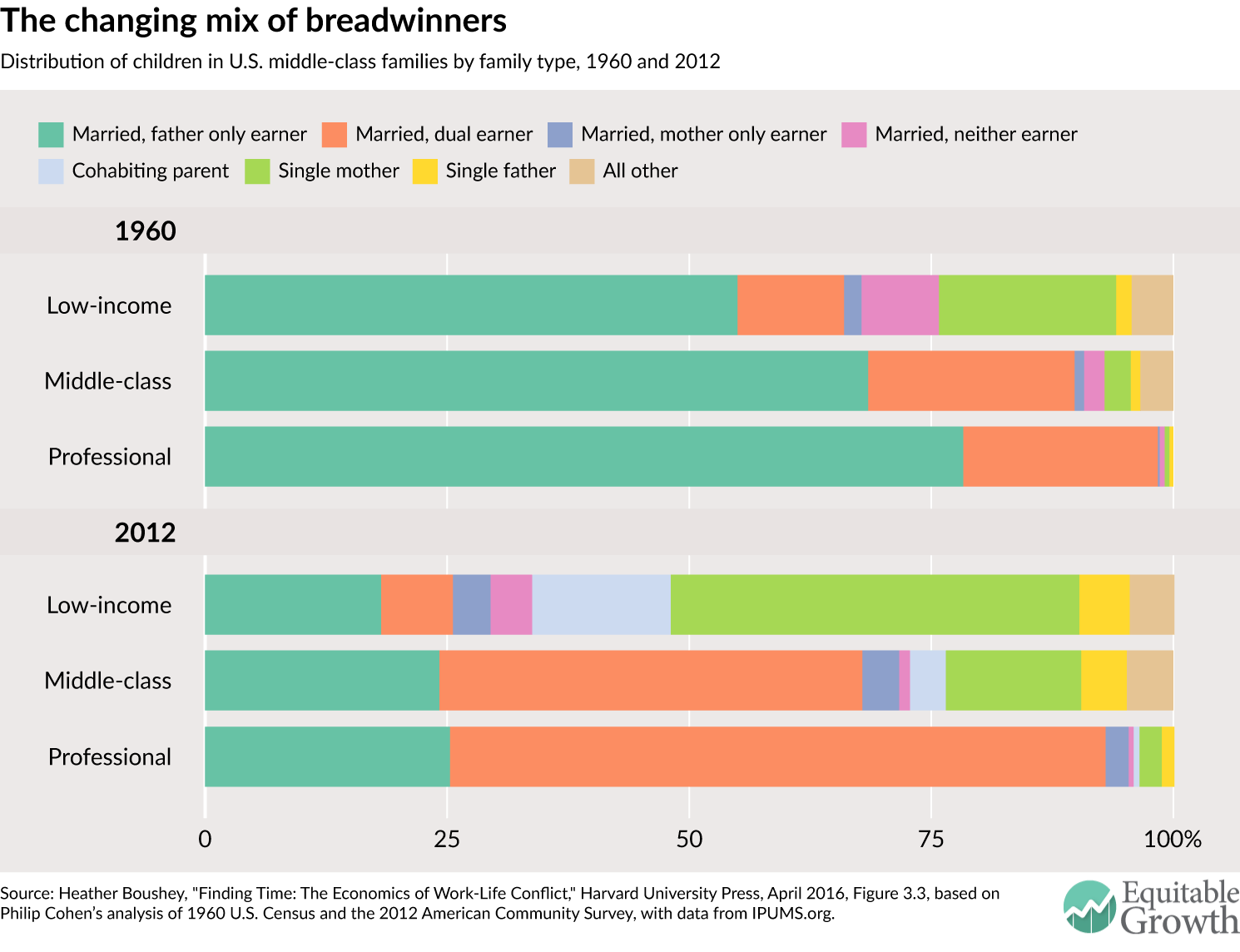

Figure 1

Overall, income growth for families in the bottom 99 percent was good again in 2015 as it had been last year, marking the second year of real recovery from the income losses sparked by the Great Recession of 2007-2009. After a large decline of 11.6 percent from 2007 to 2009, real incomes of the bottom 99 percent of families registered a negligible 1.1 percent gain from 2009 to 2013, and then grew by 6.0 percent from 2013 to 2015. Hence, a full recovery in income growth for the bottom 99 percent remains elusive. Six years after the end of the Great Recession, those families have recovered only about sixty percent of their income losses due to that severe economic downturn.

In contrast, families at or near the top of the income ladder continued to power ahead. These families at or near the top of the income ladder did substantially better in 2015 than those below them. The share of income going to the top 10 percent of income earners—those making on average about $300,000 a year—increased to 50.5 percent in 2015 from 50.0 percent in 2014, the highest ever except for 2012. The share of income going to the top 1 percent of families—those earning on average about $1.4 million a year—increased to 22.0 percent in 2015 from 21.4 percent in 2014.

Income inequality in the United States persists at extremely high levels, particularly at the very top of the income ladder. Figure 1 shows that the incomes (adjusted for inflation) of the top 1 percent of families grew from $990,000 in 2009 to $1,360,000 in 2015, a growth of 37 percent. In contrast, the incomes of the bottom 99 percent of families grew only by 7.6 percent–from $45,300 in 2009 to $48,800 in 2015. As a result, the top 1 percent of families captured 52 percent of total real income growth per family from 2009 to 2015 while the bottom 99 percent of families got only 48 percent of total real income growth. This uneven recovery is unfortunately on par with a long-term widening of inequality since 1980, when the top 1 percent of families began to capture a disproportionate share of economic growth.

The 2015 numbers on income have been built using the new filling-season statistics by size of income published by the Statistics of Income division of the IRS. These statistics can be used to project the distribution of incomes for the full year. We have used these new statistics to update our top income share series for 2015, which are part of our World Top Incomes Database. These statistics measure pre-tax cash market income excluding government transfers such as the disbursal of the earned income tax credit to low-income workers.

Timely statistics on economic inequality are key to understanding whether and how inequality affects economic growth. Policymakers in particular need to grasp whether past efforts to raise taxes on the wealthy—in particular the higher tax rates for top U.S. income earners enacted in 2013 as part of the 2013 federal budget deal struck by Congress and the Obama Administration—are effective at slowing income inequality.

The latest data from the IRS suggests the 2013 reforms proved to be fleeting in terms of reducing income inequality. There was a dip in pre-tax income earned by the top one percent in 2013, yet by 2015 top incomes are once again on the rise—following a pattern of growing income inequality stretching back to the 1970s.

—Emmanuel Saez in a professor of economics at the University of California-Berkeley and a member of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth’s steering committee.

Photo by Steve Johnson, via flickr