Overview

Many workers in the United States are at the mercy of unpredictable scheduling practices, often facilitated by new technologies where computer algorithms create employee schedules based on projected consumer demand. Unpredictable schedules can be found in many occupations but are most common in retail and service industries—the very industries in which workers also face a lack of benefits, poor working conditions, and insufficient pay. For many, unpredictable schedules are caused by “just-in-time” scheduling software, which seeks to match the correct number of workers with demand but wreaks havoc on workers who have no control over a schedule that changes from day-to-day, or even hour-to-hour. This issue brief examines the economic and legal context in which unpredictable scheduling became popular, and then looks at the consequences for individuals, firms, and the broader U.S. economy.

Download FileWorking by the hour: The economic consequences of unpredictable scheduling practices

Read the full PDF in your browser

Introduction

The growing stratification of income and wealth is a well-established problem within the United States, yet control over one’s time is an often overlooked form of inequality that affects millions of Americans. Unpredictable schedules, characterized by little to no control over one’s work hours, and erratic, on-call, or rotating shifts are increasingly common for workers up and down the income ladder. There are lots of reasons for these practices. The Internet means that some professional, white-collar workers can be “home” yet still monitor their email at all hours. Doctors and nurses often stay late to finish paperwork or finish up with a patient and are often on-call.

Unpredictable schedules, however, are more often a symptom of a business model in the retail and service industries that treats labor only as a cost to be contained rather than a source of productivity and competitive advantage. Many employers have implemented so-called “lean labor strategies” or “workplace optimization systems,” which seek to align the number of staff at work at any given time with consumer demand in as close to real time as possible. This strategy is made possible by “just-in-time” scheduling software, now common in the low-wage retail and service industries. This software uses computer algorithms to generate schedules finely tuned to predicted consumer demand, accounting for factors such as time of day, weather, the season, or even a nearby sporting events. In doing so, these practices seek to ensure that businesses optimize the number of workers on hand on an hourly—or even shorter—basis.1

Unpredictable scheduling practices shift the risk of doing business away from firms and onto workers and their families. In doing so, workers end up with little—or no—control over their time. At first glance, this strategy may appear to make good business sense. But in practice, there is evidence for variety of negative economic ramifications for families, firms, and the broader U.S. economy. Unpredictable schedules affect who can take these jobs and how productive workers may be on-the-job, both of which have an impact on business profits. Families experience fluctuations in income, diminishing their ability to buy goods and services, which affects both family well-being and overall economic demand. Unpredictable scheduling practices also prevent workers from being able to plan other aspects of life—everything from childcare to attending school or taking a second job—all of which have measurable negative effects on family life and children’s outcomes as well as our economy more generally.

There are a variety of options for policymakers and businesses that could not only improve on-the-job productivity, but also help families function—options that are good for our current and future economy alike. Lawmakers are beginning to take notice. After San Francisco enacted the Retail Workers Bill of Rights in 2014 restricting employers’ ability to impose unpredictable and last-minute schedules on their employees, 18 different states and municipalities introduced similar work-hour legislation in 2015.2 Following a yearlong inquiry into retailer’s use of on-call scheduling, New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman recruited attorney generals from eight states and the District of Columbia to open their own investigations this year. In response, six major retail brands so far have agreed to end their on-call scheduling.3

While these local actions are an important first step, millions of workers remain subject to unpredictable scheduling practices because there is not yet a federal law governing schedule predictability. The Schedules That Work Act, introduced in 2015 by Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Representative Rosa DeLauro (D-CT), addresses schedule predictability on a national level. If passed, it would encourage scheduling predictability by granting workers employed at firms with 15 or more employees the right to request a flexible schedule.4 Any effective policy also must address enforcement issues because the laws that do exist at the state and local level are too often unenforced, especially among employers of low-wage workers.

What do we know?

There is growing evidence that unpredictable schedules are widespread and increasingly common. Because the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics does not regularly track these kinds of scheduling practices, it’s difficult to know precisely how the prevalence of unpredictable scheduling nationwide has changed over time. Empirical work from a variety of sources, however, shows that these practices are widespread, especially within the retail, restaurant, transportation (airline travel and package delivery), and hospitality (hotels and catering) sectors of the economy.5

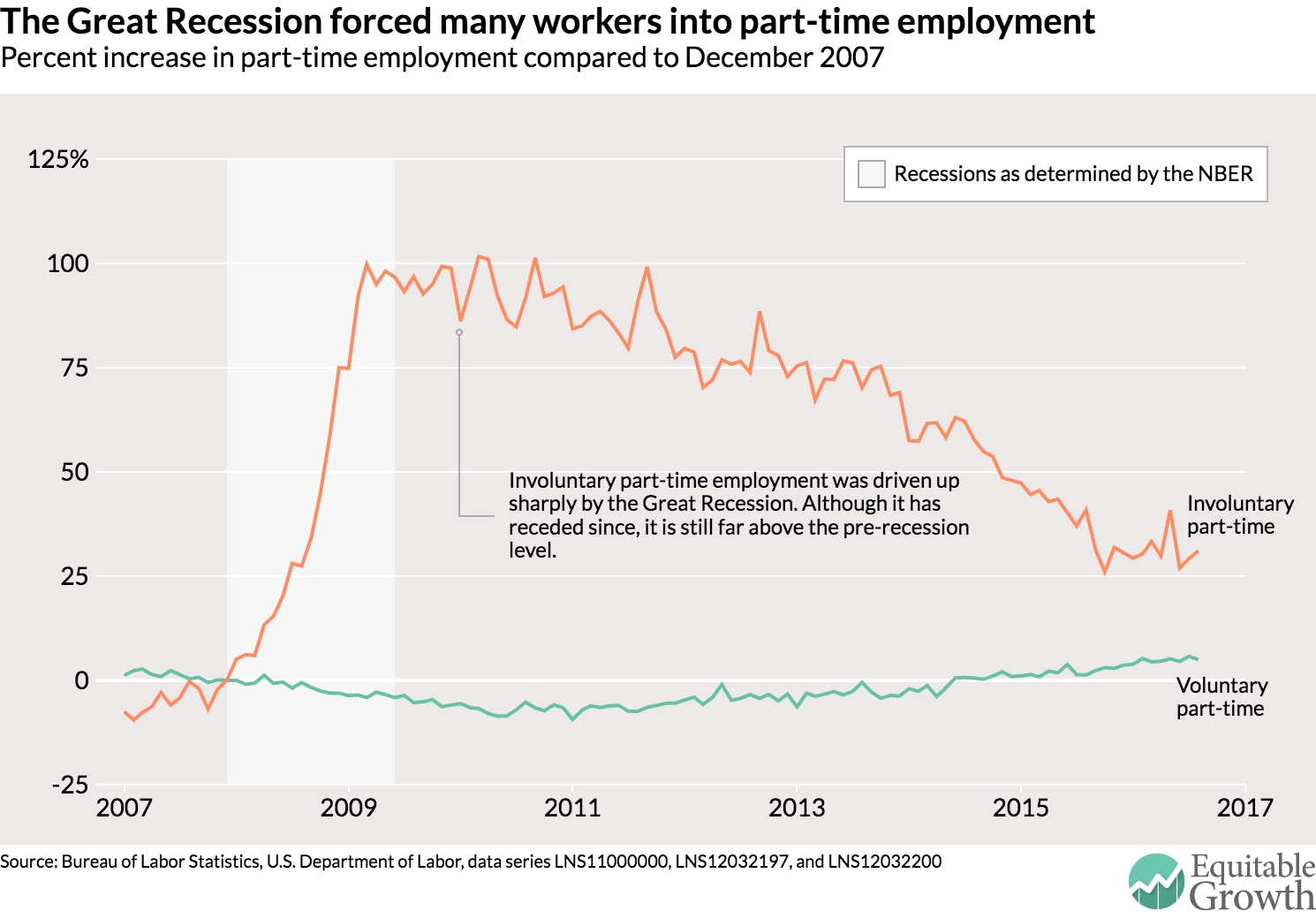

A 2015 report by Pennsylvania State University-Abington’s Lonnie Golden found that, as of 2010, 10 percent of the overall workforce deals with an irregular work schedule or on-call shifts. Golden admits, however, that this estimate is a conservative one, as the data he uses from the General Social Survey (compiled by NORC at the University of Chicago) is likely to underreport the incidence of “irregular” work schedules.6 Golden’s research also finds that low-income workers are much more likely to have irregular or on-call hours, and that working part-time more than doubles a workers’ chance of having “variable hours.” Other research also finds that the majority of part-time workers face weekly or monthly fluctuations in work hours that were not due to illness, overtime, or vacation—even before the Great Recession of 2007-2009.7

University of Chicago’s Susan Lambert, Peter J. Fugiel, and Julia Henly worked with the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics to add questions about schedules to another data set, the National Longitudinal Study of Youth. They find that more than a third of “early career” employees are given a week or less advance notice of their schedules. Among those surveyed, short notice is more common among part-time workers (47 percent) compared to full time workers (39 percent).8 These data also shows that among young workers, those who are low-income are most likely to have unpredictable schedules. While 57.1 percent of young professional workers know their schedules a month in advance, the same is true for only 34.0 percent of young workers in low-income families.9

Researchers at the JP Morgan Chase Institute recently examined scheduling practices by looking at a sample of data from the customers of its parent company, JP Morgan Chase & Co, the largest U.S. bank. The institute finds that more than half—55 percent—of its sample experienced more than a 30 percent month-to-month change in total income. Over half of that volatility—53 percent—was from labor income, mostly (86 percent) from people who have not changed jobs. According to the institute’s analysis, changes in hours worked, bonuses, or other earnings factors account for 72 percent of the change in paychecks within a specific job (and the rest was due to 5-week months).10

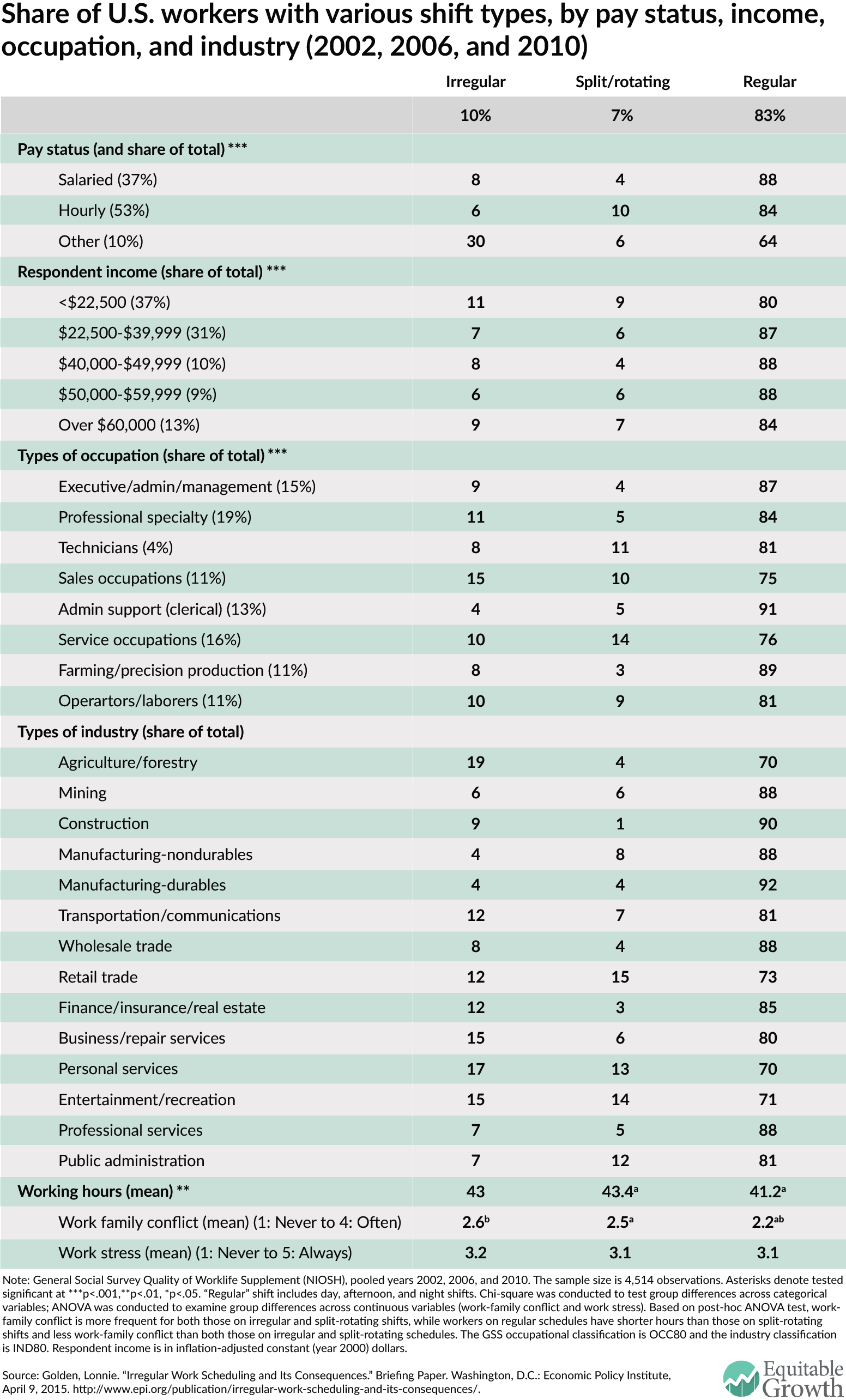

Scheduling practices vary across industries, which means that the share of workers with variable workweeks also varies across industries. Agriculture/forestry, personal services (which include occupations such as childcare and eldercare workers, hairstylists, personal trainers, and tour guides, among others), business/repair services, retail trade, and entertainment/recreation have the highest share of workers with irregular work hours. Professional services, public administration, mining, and manufacturing have the lowest.11 (See Table 1.)

Table 1

Because of the variance in scheduling practices across industries, many studies look at a specific industry. Julia Henly of the University of Chicago, Elaine Waxman of the Urban Institute, and H. Luke Shaefer of University of Michigan, found that 60 percent of retail employees interviewed said that their schedules changed “a lot” or a “fair amount” during a given week.12

- An analysis of 2012 New York City retail workers by Georgia State University College of Law’s Charlotte Alexander and University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Anna Haley-Lock, which found that 55 percent of workers were given no more than a week’s notice of their schedules. These workers reported average fluctuations in work hours of 12-to-16 hours from week to week.13

- A study of 6,000 retail workers led by Jennifer Swanberg of University of Maryland and Jacquelyn B. James of Boston College found that 59 percent of surveyed workers faced weekly changes in work days and shift times.14

- An analysis of the 2008 National Changing Workforce Study by Liz Watson of the National Women’s Law Center and Jennifer Swanberg at the University of Maryland found that 20 percent to 30 percent of workers see their hours reduced during slow periods.15

- A recent study of 436 Washington, DC restaurant and retail workers found that nearly half of the employees reported learning of their schedule less than one week in advance, a third received less than three-days notice, and a third of restaurant workers got less than 24-hours notice.16

Taken together, this research clearly demonstrates that unpredictable scheduling practices are sufficiently widespread to concern policymakers, especially given the burden they impose on the low-income workers and especially hourly employees. Families need these jobs and it poses a significant challenge to schedule their lives around unpredictable schedules. Further, unpredictable schedules are occurring in industries that are fast-growing, so without intervention, these trends may become more common for more workers. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, both retail sales positions and food preparation and serving positions are among the top five occupations predicted to add the most new jobs in the next decade.17

One reason that unpredictable schedules are so common is employer’s use of just-in-time scheduling software, which allows managers to adjust—and readjust—employees’ schedules during the week, day, or even in the middle of a worker’s shift. The software can break down schedules in 15-minute increments, meticulously paying attention to even the smallest fluctuations in store traffic, shaving minutes off an employee’s shift if need be.18 In practice, this often means that managers do not post schedules until they are certain of the number of hours they have to give out (determined by upper management), and the managers’ bosses seek to contain costs by holding them accountable for “staying within hours.” It also leads managers to cut scheduled hours if they have gone over their allotted budget for labor costs earlier in the week.

Of course, computer algorithms are not the only factor leading to unpredictable schedules. In fact, many of the scheduling software systems include forecasting functions that could allow workers greater input, generating more stable schedules overall. The problem is that many employers do not choose to implement the features that would provide greater schedule stability and predictability.

Furthermore, some employers require workers to remain on-call, keeping their schedules free on the chance their employers may need them. Combined, these scheduling practices mean that many workers often have little or even no advance notice of their schedules.19

Just-in-time and lean scheduling practices were first developed by the Japanese automobile industry in the 1950s to “eliminate waste” by supplying parts only as needed and when the process required it.20 In the manufacturing sector, that meant cutting down on the amount of warehouse inventory and “produc[ing] goods ‘just-in-time’ to meet customer demand.”21 Over time, the just-in-time philosophy was adapted from the production of goods to the management of companies’ workforce schedules. Walmart Stores Inc. was an early adopter in 2007, allowing managers at the giant retailer to choose employee hours based on day-to-day sales.22 Other employers soon followed suit. Today, the practice is especially widespread in the low-wage service industry, including restaurants, retail, hospitality, and care sectors, where just-in-time scheduling seeks to eliminate “excess labor” instead of the “excess inventory” of its production counterpart.23

Are these practices successful? Looking at only short-term labor costs, these practices can slash costs. The chief financial officer at Jamba Juice Company, for example, told investors in the retail health drinks maker that just-in-time scheduling helped the company cut labor costs by 4 percent to 5 percent, saving millions of dollars.24 But that doesn’t take into account the hidden costs, both for firms and the economy as a whole. It is not uncommon for workers subject to on-call shifts to be called in even when they were not scheduled to work, or to arrive at work for a scheduled shift only to be sent home without pay.25 This is particularly burdensome for low-income workers, considering that they spend a disproportionate amount of time and income on commuting compared to those further up the income ladder.26

There is still much to learn about unpredictable schedules in terms of the individuals and occupations that they affect. While many scholars are researching this topic, a lack of high-quality data hampers their ability to gain a comprehensive understanding. A good place to start in the public policy arena would be to continue to include questions about schedule predictability in our nation’s regularly conducted surveys.

Unpredictable schedules: The full economic implications

A growing body of literature spanning academic disciplines documents how broad changes in economic, social, and political institutions over the past 40 years transformed the organization of work. The service and care sectors, for example, have grown significantly since the 1960s as many women looked for employment outside the house, fueling the demand for many personal services that were previously done in the home, such as cleaning, cooking, childcare, and caring for the aged or sick.27 Retailers soon expanded their hours into the evening and weekends, as their traditional 9-to-5 hours meant missing out on business from a large share of the working population. The rise of dual-earner families’ income also meant the upsurge in popularity for night and weekend entertainment and recreation.28 Today in large cities it is no longer an oddity to find 24-hour restaurants, gyms, stores, delivery services, or even spas.

Many of these employers rely on just-in-time schedules while also paying low wages, providing few if any benefits, using temporary workers, and sometimes sub-contracting entire operations—manifestations of a “low-road” business strategy.29 This model may have short-term benefits for a particular employer, but it also has costs and hidden—and harmful—short- and long-term ripple effects on these firms and throughout our economy by

- ignoring the hidden costs and labor demand issues, such as turnover and absenteeism;

- negatively affecting the relationship between labor and productivity and profitability, especially in service industries;

- transferring the risk of doing business to workers and their families, which in turn reduces family income and disproportionately affecting women and people of color; and

- adversely affecting the quality of workers and overall U.S. labor supply, which inflicts measureable harm on the next generation of workers.

We examine each of these consequences in turn.

The hidden costs of unpredictable scheduling, such as turnover and absenteeism

Employers frequently require full-time availability to ensure there are always enough workers during busy periods, but then fail to give full-time hours. But once employed, many low-wage employees—especially those with care responsibilities—are fired or forced to quit in favor of seeking a job that provides more hours or has more flexibility. This approach treats workers’ time as simply another variable in a cost equation, yet it can create problems by undermining productivity and sparking higher turnover.30 University of Chicago’s Susan Lambert and Julia Henly surveyed 139 retail stores from 2007 to 2008 and found that a substantial share of both full- and part-time employees leave their job in the course of a year: 73.8 percent of full-time employees and 107.3 percent of part-time employees. The store managers themselves report unstable, inadequate hours and meager wages as the main reasons their employees leave.31

Turnover is not only disruptive to workers but also costly to employers. Research demonstrates that replacing workers is expensive, regardless of how much they get paid, because selecting, recruiting, and training new workers requires managers and new employees to take time away from their primary responsibilities. Even once new workers are trained, their lack of experience means that they aren’t as familiar with their duties or may not be as committed to the organization compared to workers with longer tenure, both of which affect a company’s productivity and turnover rate.32

High turnover also affects business operations more generally. It requires employees and managers to focus their energy on new employees rather than engage in other more profit-generating activities, such as improving customer service or product quality.

These costs come into telling perspective once they are quantified in numerical terms. A report by Equitable Growth’s Heather Boushey and Sarah Jane Glynn of the Center for American Progress found that across a variety of studies, research shows that it costs about one-fifth of a worker’s annual salary to replace that worker regardless of the salary paid on the income spectrum.33 And a study by Cornell University’s Rosemary Batt and Jae Eun Lee, and Ohio State University’s Tashlin Lakhani finds that the costs of employee turnover within a small, moderately priced restaurant of 30 employees total about $18,200 per year. That suggests that a large company with 100 restaurant locations could lose $1.82 million annually due to turnover costs.34

This reality is already clear to many employers. George Kelsey, the director of training for Culver Franchising System Inc, a Midwestern fast-food restaurant chain, estimates the cost of turnover to be about $1,000 per employee across Culver’s establishments. Kelsey reports that while many companies often fail to fully account for these costs, focusing primarily on labor expenses, “we treat high turnover costs the same as high labor costs.”35

The relationship between scheduling, predictability, and profitability

Unpredictable schedules create other problems that can eat into profits, including poor customer service and persistent understaffing. Many firms tend to view labor as a “cost-driver” rather than a “sales-driver,” and thus concentrate on curtailing costs. But research shows that cutting corners in terms of staffing affects profits and productivity.36 So why do retailers do it? The financial benefits to reducing labor costs are, as Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Zeynep Ton says, “direct, immediate, and easy to measure, whereas the less desirable effects are indirect, long term, and difficult to measure.”37

That means unpredictable schedules and the resulting high turnover may actually be counterproductive, depressing sales because of poor customer service. Joan Williams, founding director of the University of California’s Hastings Center for WorkLife Law, says that “new employees do not have a strong grasp of the product and a high level of commitment to the organization.”38 In the short-term, this could mean customers leaving without buying anything, or losing regular consumers to competitors. In the long term, social media websites such as Yelp, Facebook, and Twitter have made businesses more worried than ever about how word-of-mouth may damage their reputation.39

Firms also do not account for how persistent understaffing eats into profits. Store traffic can be unpredictable, making some overstaffing or understaffing inevitable. But many corporations hold managers accountable for containing labor costs, and give them a specific allocation of work hours that managers are allowed to distribute to employees. Under pressure to “stay within hours,” managers may schedule too few workers to meet customer demand. Problems with understaffing at Walmart, for example, have led to a widespread airing of grievances against the store not only from customers but also from employees. Walmart employees have reported how persistent understaffing resulted in problems such as long lines, throwing away unstocked inventory, and missed sales opportunities.40

Recent research quantifies these losses. Vidya Mani of Pennsylvania State University, and Saravanan Kesavan and Jayashankar M. Swaminathan, both of University of North Carolina’s Kenan-Flagler School of Business, surveyed 41 stores of a large retail chain, finding “systematic understaffing during peak hours.”41 The effect was a 7.0 percent decline in profitability. Overstaffing, in contrast, only reduced profitability by 1.1 percent.42 Research by Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Zaynep Ton and Harvard Business School’s Ananth Raman supports these findings. Looking at data from over 250 stores of the Borders bookstore chain, Ton and Raman found that a one-standard-deviation increase in labor levels at an individual store boosted profit margins by 10 percent over the course of the year.43

Many managers are aware these scheduling systems harm the company profitability. Yet the pressure to “stay within hours” makes it difficult for managers to fulfill their companies’ business objectives. Under pressure to meet short-term performance requirements, some feel forced to cut employee hours in the face of declining sales—even when they know that doing so may be costly in other respects.

While minimizing employee costs as a way to maximize profits is one model of productivity, it is not the only way to boost a company’s bottom line. Companies such as Costco Wholesale Corp., Trader Joe’s Co., and QuikTrip Corp. all successfully operate under the philosophy that investing in labor through higher wages, better schedules, and increased training can improve the bottom line. Doing so enhances operational efficiency and customer service, which boosts profits.44

Unpredictable scheduling transfers business risks to workers and their families, disproportionately affecting women and people of color

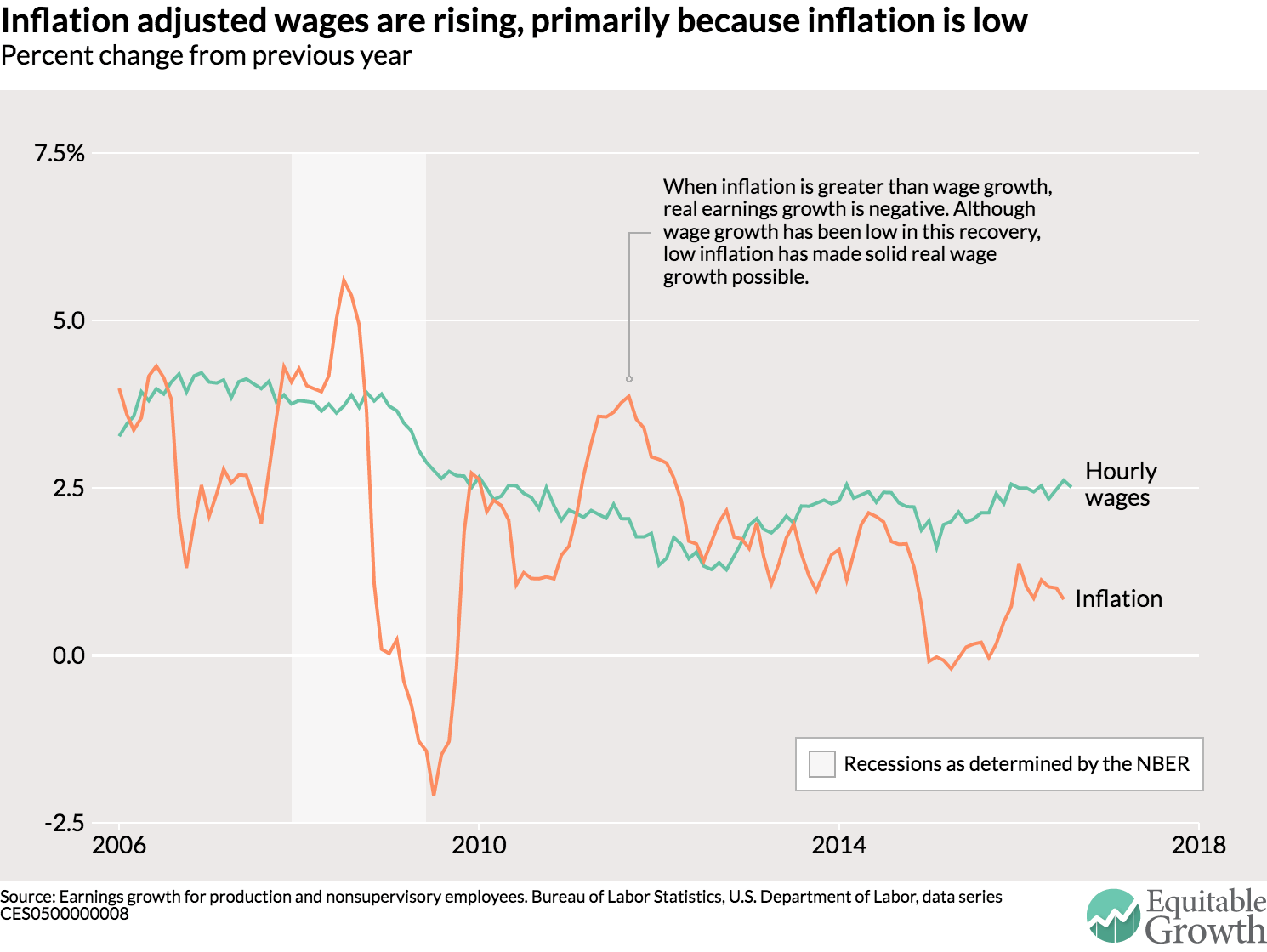

A healthy economy requires people not only to serve as workers within these businesses but also to create strong consumer demand for the goods and services that these businesses supply to the marketplace. Workers with unpredictable schedules also experience volatility in the number of hours they work—and, for hourly workers, volatility in income. For middle- and high-income workers with unpredictable schedules, that often means longer workweeks or mandatory overtime. Volatility in hours for low-wage workers means that some weeks they may not be able to work enough hours to cover even the most basic expenses.45 Unpredictable schedules can also prevent workers from achieving upward mobility because many are not able to maintain a long-term financial plan that could help them plan for retirement or save for an education.

The consequences of unpredictable schedules fall harder on women, perpetuating existing gender inequities. The demographic makeup of the retail and restaurant industries, in which unpredictable scheduling practices are frequently found, largely mirrors the overall labor force.46

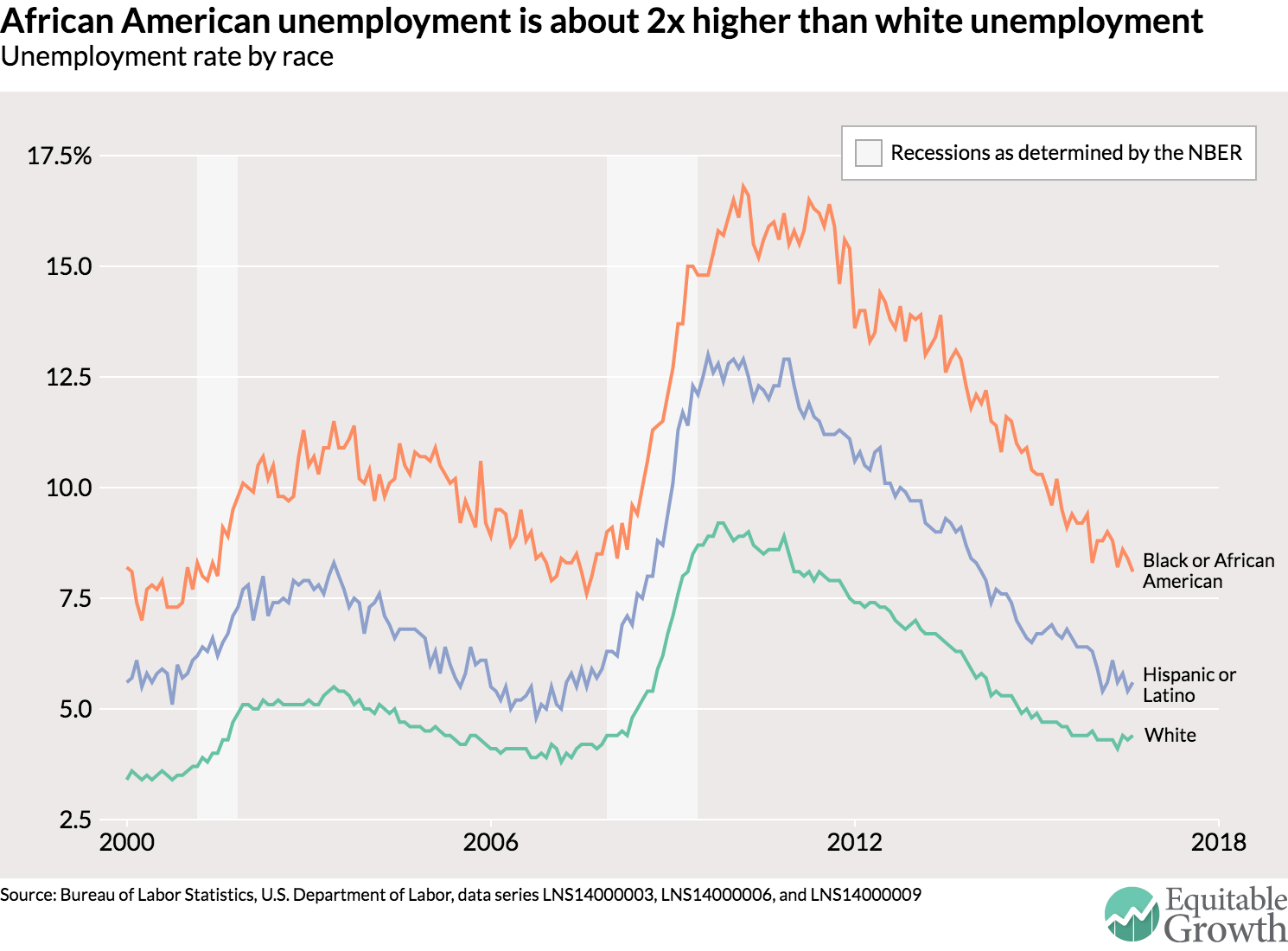

Racial inequities also are widespread within these industries, leaving workers of color—especially women—and their families bearing the brunt of the economic and family consequences of unpredictable scheduling practices. A study released by the non-profit organization Demos and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People found that black and Latino retail workers are sorted into the low-paid positions most likely to involve erratic scheduling and inadequate hours despite sharing similar levels of education and age as their white counterparts.47 It is no surprise, then, that in a survey of early career retail workers by Susan Lambert and Julia Henly, along with their University of Chicago colleague Peter J. Fugiel, the researchers found that 49 percent of blacks and 46 percent of Latino workers received their hours with a week or less of notice, compared to 41 percent of workers overall.48 Non-white workers also tend to face longer commute times compared to their white counterparts, which means greater costs in terms of time and money when they travel to work only to be turned away.49

The consequences for black workers are compounded because they are more likely than members of other major racial or ethnic groups to be the sole contributor to household income, exacerbating the hardships triggered by unpredictable and insufficient paychecks.50 Those with children may have to pay for childcare, even when they themselves did not get paid. While there are managers who understand and are responsive to their employees’ needs, a study of low-income workers found that many managers treat their workers’ inability to balance their work and home lives as a personal failing, rather than a structural issue. These managers believed that their employees used the “sick kid” excuse too often, and were instead disorganized, lazy, and lacking in work ethic.

These charges of “irresponsibility” have implicit racial overtones, mirroring stereotypes of African Americans and other minority groups as lazy. In interviews with managers in two separate studies, Boston College’s Lisa Dodson and her co-authors recorded some managers who implied that employees who wanted more schedule input were reckless for having children in the first place.51 This research contrasts other studies of elite, primarily white workers who are lauded for putting their children first.52

Insufficient hours and the highly variable incomes can have implications for government spending as either may render workers ineligible for government benefit programs such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, time off under the Family and Medical Leave Act, unemployment insurance, or certain childcare subsidies. Childcare subsidies, for example, may require that the family consistently use childcare, which may be impossible with an unpredictable schedule. And, to the extent that unpredictable schedules contribute to income volatility, it may be one piece of the puzzle of how to address homelessness among the working poor. In New York City, for example, more than one out of every four homeless families (28 percent) include an employed adult, and 16 percent of single adults living in shelters are employed. These workers are majority female and tend to work in low-wage jobs where unpredictable schedules are common, such as security guards, home health aides, and sales clerks.53

Erratic scheduling practices affect the quality of our workers and overall labor supply

Unpredictable scheduling may lessen workers’ ability to be fully productive or result in a reduction in the quality of workers who are able to take these jobs. Employers who give workers no control over schedules end up hiring only those who at least claim they have no scheduling constraints.

If employers only look for workers who have no other obligations except to be on call for hours, then they must find a pool of job applicants without outside obligations such as family, school, or even a second job. This is not the world most people live in and goes a long way toward explaining why unpredictable schedules are associated with high rates of absenteeism. Many parents need some flexibility to address day-in, day-out conflicts; one study found that within a single week, 30 percent of low-income workers disrupted their work schedules because of family obligations.54 If caregivers cannot find good jobs with good schedules then they may feel forced to leave their jobs. In fact, low-wage women are more likely to drop out of the labor market compared to those in the middle class, upending the notion that only relatively wealthier women become stay-at-home parents. Thirty-four percent of stay-at-home mothers live in poverty, compared to 12 percent of working mothers.

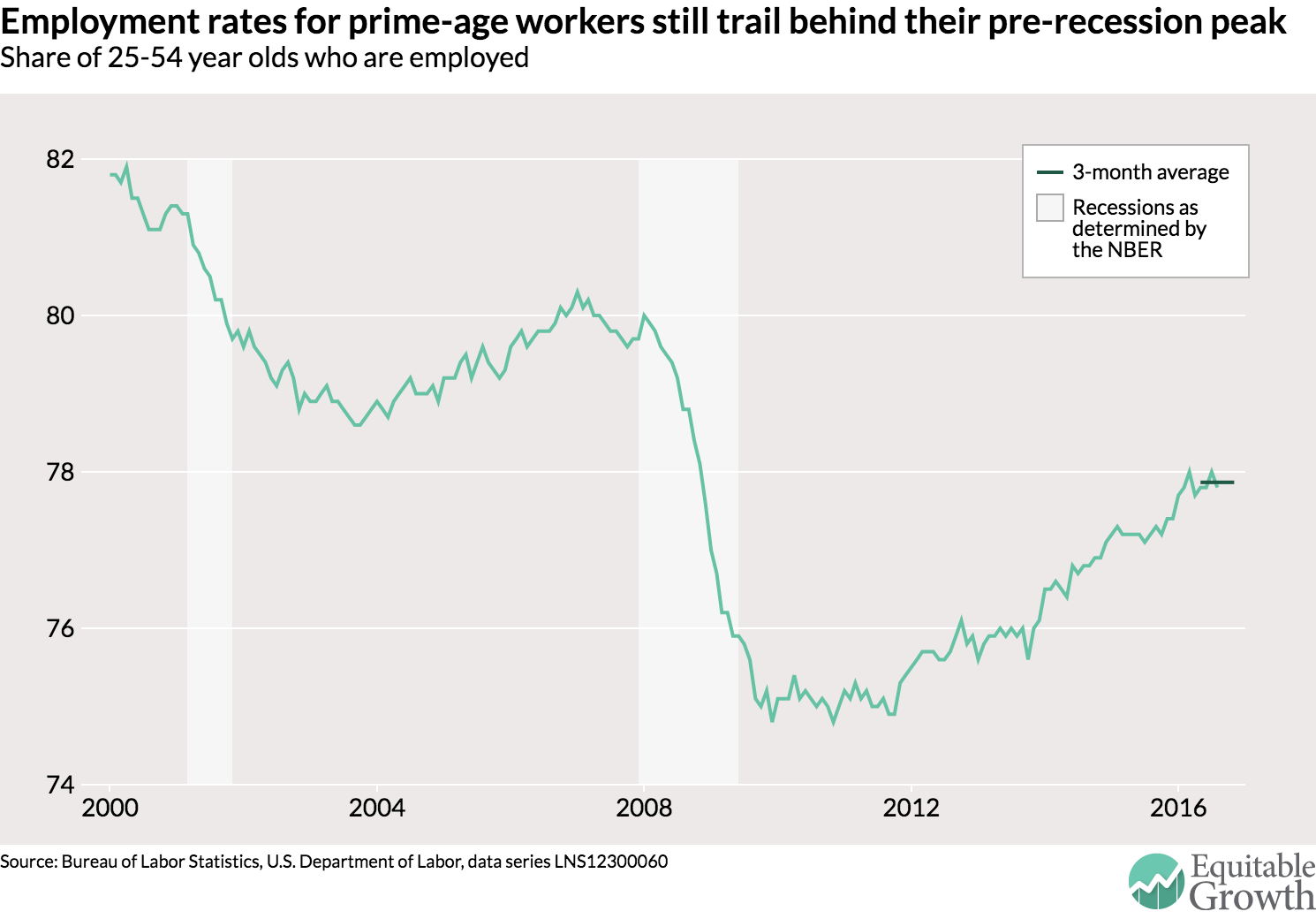

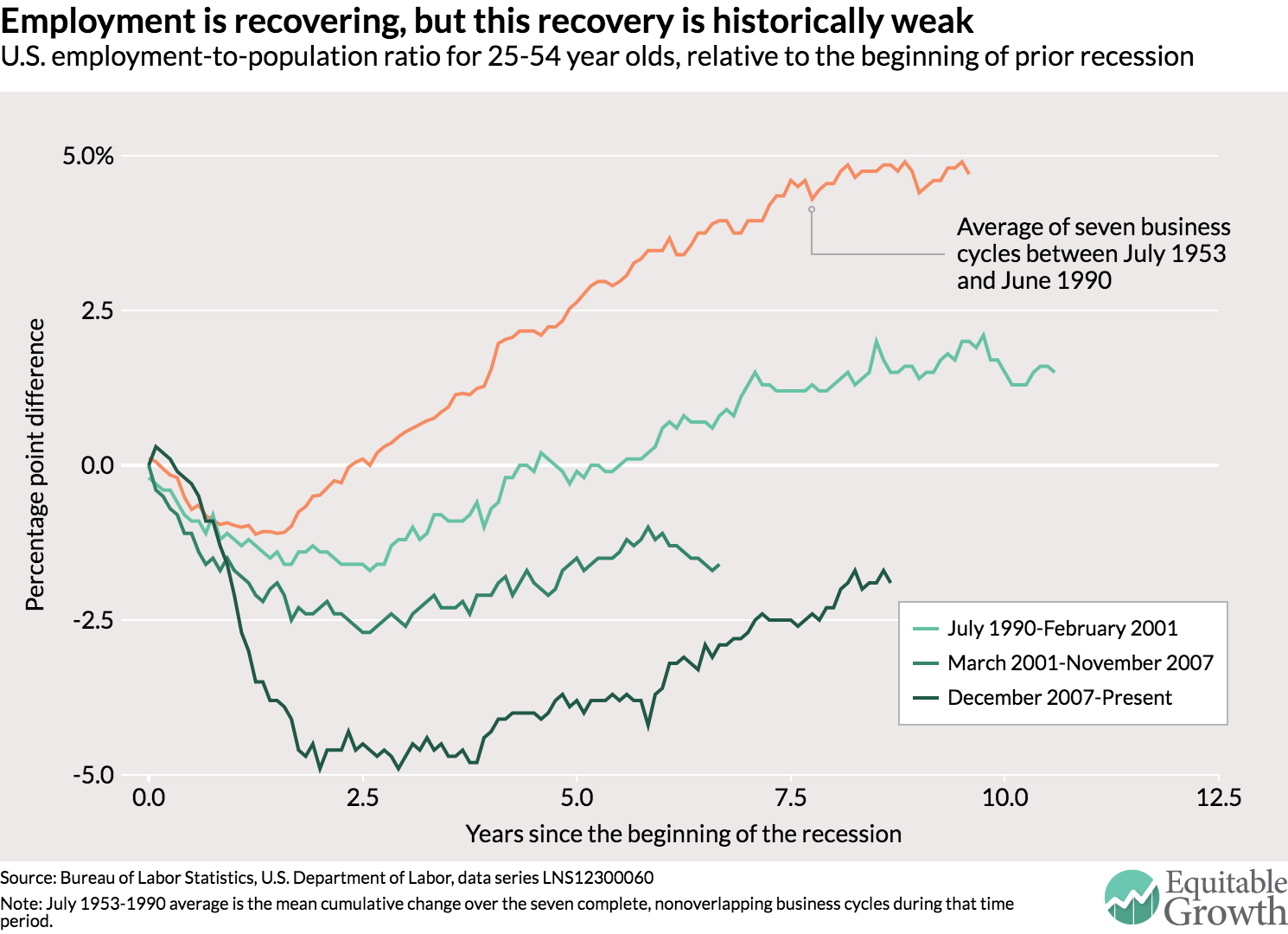

The inability of many low-income workers to balance the demands of work and home lives is having a profound impact on the economy. The United States has seen its labor force participation rate decline significantly since 2000, dropping from No. 7 among 24 member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development to No. 21 today. The participation rate of women, who still bear the majority of care responsibilities, has suffered in particular. Francine D. Blau and Lawrence Kahn of Cornell University find the lack of employer and policy supports for parents balancing work and care responsibilities to be a major factor in this phenomenon.55

Unpredictable schedules harm the next generation of workers

Economists all agree that human capital—the knowledge, skills, and talent in our potential workforce—is a critical factor for economic growth. By not investing in today’s children, we place our future economic productivity at risk.56 Isolating the effect specifically of unpredictable schedules on children’s outcomes is difficult, but there is evidence that this practice has negative consequences for families and children.57

For parents—and women in particular—unpredictable schedules can make it impossible to secure care for their children, even if they can tap childcare subsidies. Finding affordable and high-quality childcare can be challenging even for parents further up the income spectrum. Low-income parents coping with unpredictable schedules have the combined challenges of meager wages and unpredictable schedules, and usually end up piecing together informal care arrangements because it is difficult to access childcare subsidies, even if they are available.58

Erratic and nonstandard schedules are associated with negative behavioral outcomes for children. These children tend to have poorer health, do less well in school, report low self-esteem, and engage in risky or delinquent behavior. One study by New York University’s Wen-Jui Han found that toddlers of parents who work nonstandard schedules have worse skills such as memory, sensory perception, learning, problem solving, verbal communication, and expressive language.59 Another study by Pamela Joshi of Harvard University and Karen Bogen of University of Massachusetts-Boston found that preschoolers whose mothers worked nonstandard schedules had higher rates of negative behaviors such as depression, anxiety, withdrawal, and aggression.60 These problems are especially serious for African American children, since African American mothers are disproportionately represented in jobs with nonstandard work schedules.61

It is difficult to reverse patterns established early in a child’s life, which years later can impact adolescent and adult outcomes.62 Given the widespread nature of these unpredictable scheduling practices among the low-wage workforce, these schedules not only wreak havoc on our current workforce but also harm the skills of our future workforce—and therefore the productivity of our economy in the years to come.

Addressing unpredictable schedules

Unpredictable scheduling practices are perfectly legal. Yet, as outlined above, the problems—for firms, individuals, and the broader economy—associated with unpredictable schedules are large. Further, these challenges may grow without some kind of public policy intervention since the occupations in which these practices are most common—retail, the home care sector, and restaurants, among others—are all among what the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts will be some of the fastest growing occupations over the next decade.63

One important backdrop for the policy context is the demise of labor unions. Historically, collective bargaining governed working conditions for many employees, including issues such as schedule predictability. But today, only 7.4 percent of private-sector workers are covered by a union contract. That number is even lower in retail (5.3 percent of workers covered) and food services and drinking places (1.9 percent of workers covered), which are among the industries where erratic schedules are most common.64

This means workers’ ability to balance their work and home life is governed almost entirely by individual employers. While there are managers and companies out there who see the benefits of stable schedules, many more may fear that enacting better staffing strategies will put them at a comparative disadvantage compared to “lean staffing” competitors. Federal, state, and municipal policies, therefore, have a role to play. By implementing rules governing scheduling practices across the board, no one employer will be at risk. Indeed, the evidence suggests that it may help all businesses in the long run.

This section lays out private- and public-sector policy recommendations that could help create more stable schedules in a way that is more sustainable for employees and employers alike. Adapting our labor standards and rules to address today’s economy and workers will help millions of Americans and create more sustainable, equitable growth.

Private solutions

In the face of mounting pressure and evidence pointing to the costs of these harmful scheduling practices, many private companies have voluntarily overhauled their work policies. As mentioned earlier, six major retailers ended on-call scheduling after New York attorney general Eric Schneiderman launched an inquiry into their workforce policies. Walmart led the way in adopting just-in-time scheduling practices, but now the company says they are moving toward a scheduling system that they claim will better accommodates family life. By the end of this year, they have said that the company will offer some employees fixed shifts, allow employees to know their schedule 2.5 weeks in advance, and allow employees to choose their schedules using a smartphone app.

Walmart, however, has not made public how many employees will be eligible for fixed shifts or whether employees who choose fixed shifts or place reasonable limits on their schedules will be eligible for full-time employment. Further, the company has not indicated that it intends to address chronic understaffing. So it remains to be seen how far Walmart’s new policy will go toward addressing the problem of unpredictable scheduling.65

Workers also are taking matters into their own hands. Technology companies are creating a variety of new smartphone apps that purport to provide more schedule flexibility. For example, a new app called myshyft lets hourly employees switch, offload, or sign up for extra shifts. So far, the app-maker, Shyft Technologies Inc., reports that 12,000 U.S. employees at Starbucks Corp., 7,500 workers at McDonald’s Corp, and 3,500 workers at The Gap Inc.’s Old Navy retailing unit have signed up. This app is one example of the way that technology can be employed to generate more stable and predictable schedules, and be part of the solution.

But while the app is helping many employees better tailor their schedules to their outside responsibilities, they do so without the explicit cooperation of their employer. Some managers have adopted Shyft’s technology, posting the entire schedule on the app and letting their employees choose their own schedules. But there is a concern that, as the app becomes more popular, there will be pushback from employers who resent the loss of control over their employees’ schedules.66

In 2014, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth funded Joan Williams and Susan Lambert to work with the Gap, Inc. to develop and evaluate a pilot intervention that takes a comprehensive approach to improving multiple dimensions of work schedules in hourly retail jobs, specifically, schedule stability, predictability, adequacy, and control. Data collected throughout the nine-month study period demonstrate the feasibility of improving scheduling practices in retail and help to identify larger business practices that facilitate, and undermine, the ability of frontline managers to deliver better schedules to sales associates. Outcome analyses, currently underway, draw on multiple sources of data (scheduling and payroll data from firm systems; interviews with store managers; surveys of sales associates) to examine how the intervention is related to employee-level outcomes (financial hardship, stress, interferences with caregiving, school, additional employment, health) and store-level outcomes (conversion rates, sales, and turnover).

The Gap and other companies that are revamping their scheduling practices are partly motivated by good business reasons to move to more stable schedules. The research shows that, even within businesses that have fluctuations in labor demand, there is significant amount of existing stability in weekly hours. When Lambert and Henly studied just-in-time schedules in the retail sector, they found that for almost two-thirds of the stores, more than 80 percent of hours stayed exactly the same week after week—a fact that surprised many managers. The problem, the researchers found, rests in the managers’ tendency to delay finalizing the schedule until the last minute, waiting for new information. Managers could capitalize on the existing stability in hours in a way that provide workers with more advance notice and regularity.67

Being able to do so, however, also requires addressing managers need to “stay within hours.” A study of hourly jobs in Chicago found that managers are called several times a day in order to inform them of the hours ratio for the next few hours. Giving managers the ability to hit their target ratio by the end of the week, rather than expecting to hit it every hour, could make it possible for managers to deliver greater schedule stability and predictability to workers.68

Further, while technological solutions can make it easier for employees to swap shifts or for employers to comply with new work hours standards, but they cannot obviate the need for a policy floor. Flexibility is just one dimension of sustainable work hours; Shyft and other apps do not deliver adequate or stable weekly incomes or schedules that allow workers to plan in advance for childcare.

Public policy solutions

The Fair Labor Standards Act, the federal law that governs wage and hours protections for workers, has no minimum-hours mandate and does not require employers to create regular, predictable schedules. The FLSA was enacted in 1938 to address the key labor issues of the day, such as prohibiting child labor, establishing a minimum wage, and defining a regular workweek to be limited to 40 hours.69

The FLSA sought to restrain overwork, but did not seek to address schedule predictability.70 The overtime provisions require that workers covered by the law—those paid by the hour and certain lower-paid salaried workers—be paid 150 percent of their usual hourly wage for any hours they work beyond 40 in a given week. The law does not address employee-led flexibility, scheduling issues, predictability of hours, sufficient hours, or part-time parity.71 Today, while many workers struggle with overwork (an issue we laid out in our report, “Overworked America” ), many others face unpredictable work hours.72 Yet there is no national law to protect workers from erratic schedules.73

Knowing what we do, however, points to a few solutions that policymakers at the federal, state, and local level have already begun to develop, namely:

- A workers’ Bill of Rights

- Reporting pay laws

- Right to request laws

- The Schedules that Work Act

Let’s briefly examine each of these policy prescriptions in turn.

Workers’ Bill of Rights

There is no national law to protect workers from unpredictable schedules, but there are a variety of new ideas being tested among state and local governments. In 2014, San Francisco became the first jurisdiction to penalize employers who alter their employees’ schedule through the passage of the Retail Workers Bill of Rights. This new law requires that:

- Any retail chain with 40 or more locations that employs 20 or more employees within the city provide two weeks advance notice of work schedules

- Employers that impose schedule changes with less than seven days’ notice will be required to pay additional “predictability pay”

- Employers offer more hours to their existing qualified part-time employees before hiring new workers

- Employers provide two-to-four hours of pay to an employee who is “on-call” for a shift that is cancelled less than 24 hours ahead of time

- Employers pay part-time employees the same starting hourly wage as full-time employees in the same position74

Many other localities are now following suit. Following passage of San Francisco’s 2014 legislation, 18 different state and local legislatures introduced their own scheduling legislation. In 2016, campaigns are actively pushing predictable scheduling legislation in Oregon, Minnesota, Connecticut, and Massachusetts. And lawmakers in Seattle, Washington, DC, San Jose, and Emeryville, CA are actively debating what predictable scheduling legislation should look like in these locales.75

Reporting pay laws

Seven states and the District of Columbia have enacted so-called “reporting-pay laws” (California, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Hampshire, New York, New Jersey, and Rhode Island). These laws create a disincentive for employers to send employees home early by requiring employers to pay their workers a minimum number of hours for any scheduled shift that their employees report to. In places where these laws are in effect, employers cannot demand that employees show up for work but then send them home without pay. These laws vary in their scope, with some states exempting various industries.76

As of now, there is no comprehensive analysis of the effects of these laws’ implementation. What we do know is from two recent studies. University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Anna Haley-Lock finds that restaurants in Vancouver, which are subject to provincial reporting pay laws, tended to keep employees at work during slow shifts and assigned them “side work” such as restocking or deep cleaning.77 Haley Lock and Georgia State University College of Law’s Charlotte Alexander, finds that reporting pay laws inflict a limited financial burden on firms, and are effective at deterring managers from cutting shifts short.78

One concern with reporting-pay laws is that they rely on the workers to file lawsuits to enforce their rights rather than on government inspections or enforcements. Yet, many workers, especially low-wage workers, may be unaware of their legal rights, remain silent for fear of retaliation, or lack the financial resources to obtain an attorney if litigation is required.79 While reporting-pay laws are promising, their impact may be compromised if they cannot be effectively enforced.

Another challenge with these laws is that they were enacted before the advent of cell phones made it easy for employers to contact workers shortly before their shift to cancel them, or require them to call in the night before (or a few hours before) to see if they were needed. The United States Courts for the Ninth Circuit is currently hearing a case that will determine whether California’s reporting-pay law applies to on-call shifts because the worker is “reporting to work” telephonically when they call in. There is an effort to modernize reporting pay by clarifying that it is required in all cases where a shift is cancelled or shortened with less than 24-hours’ notice—even if it’s before an employee physically appears at the worksite.80

Right to request laws

“Right-to-request” laws give employees the right to request changes to their schedules without fear of retaliation.81 Such laws are now in effect in Vermont, San Francisco, and Berkeley, CA. Federal workers also now have the right to request, following President Obama’s recent implementation of this policy within the federal government.82 These laws establish a process that allows employees to discuss their scheduling needs with their employer without fear of retaliation. Employers do not have to grant the request, but they can only deny it on business grounds so long as they take the request seriously. In Vermont’s legislation, for example, employers may refuse a request if it will create a cost burden or limit the employer’s ability to meet demand, among other reasons. Here, too, there is no comprehensive study as the first of these laws was only passed in Vermont in May, 2013.

We do, however, have evidence on their effectiveness from other countries. The United Kingdom, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Germany, and Australia all have some form of right-to-request laws in place. In two different studies, these laws were found to be effective at limiting workers’ work-life conflicts. These studies, however, took place in countries with greater union coverage than in the United States, meaning that employees could ask a union representative to help them approach their supervisors. In the United States, employees must take the initiative to learn about and take advantage of the policy on their own.83

The Schedules that Work Act

At the federal level, building on these models at the state and local level, policymakers introduced the Schedules That Work Act in 2015, which similarly addresses both on-call scheduling practices and predictability. This bill, introduced Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Representative Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) addresses a multitude of problems associated with unpredictable scheduling. The proposed legislation applies to all companies with more than 15 employees. In particular, it does the following:

- Guarantees workers the right to request more flexible or predictable work arrangements without retaliation: When the request is made for certain “priority” reasons, the employer must grant the request.

- Requires reporting pay: an employer must pay their worker at least four hours of wages if they report to work without being permitted.

- Requires call-in pay: an employer must pay at least one hour of wages if they require an employee to call in less than 24 hours before the start of a shift to find out whether they have to work.

- Requires advance notice of schedules: employers must give employees their schedule at least 14 days in advance. If an employee’s schedule changes with less than 24-hours notice then the employer would pay a “predictability penalty” of one hour of pay for each changed shift (except when the shift change is due to an unexpected employee absence).

Legislation alone cannot completely eliminate scheduling abuses by employers, but a federal standard would provide an important marker that states and localities could improve upon. The federal bill’s predictability pay component does disincentivize schedule changes but does not make an effort to promote gender and racial equity—two dimensions along which workers often experience schedule abuse. And the bill does not address problems of inadequate/volatile hours or spreading work among a large part-time workforce. Yet alongside setting a floor for policy, this law also could motivate the private sector to invent new ways to balance labor costs and profits, ushering in a shift in the way we think about employment practices.

Conclusion

While employers’ use of unpredictable schedules or just-in-time schedules is seen as a way to boost profits by cutting labor costs, taking a more holistic view reveals these practices can cause harmful ripple effects for firms, families, and the economy. Irregular schedules transfer the risk of doing business to workers and can harm a company’s productivity as well. Combined with the long-term costs to our economic productivity, this issue brief should compel businesses and policymakers alike to rethink the importance of worker schedules.