Between the sleepless nights, routine doctors visits, endless baby supplies, and childcare arrangements, having a child, to put it mildly, is a mammoth investment. Parents put a significant amount of time and money into preparing for and rearing a newborn, which has tremendous pay-offs for a child’s development in the longrun. Despite the well-understood temporal and pecuniary chaos that is pregnancy and early parenthood, there is relatively little quantitative documentation on just how much a new child affects household finances.

In a new working paper, Alexandra Stanczyk, a postdoctoral scholar at University of California-Berkeley’s School of Social Welfare, contributes to this literature, exploring how U.S. household economic well-being changes in the year leading up to and following the birth of a child. Harnessing the monthly longitudinal panel data in the Survey of Income and Program Participation, Stanczyk tracks three different measures of economic security, all of which demonstrate that there are substantial decreases in household economic well-being around the birth of a child.

1.

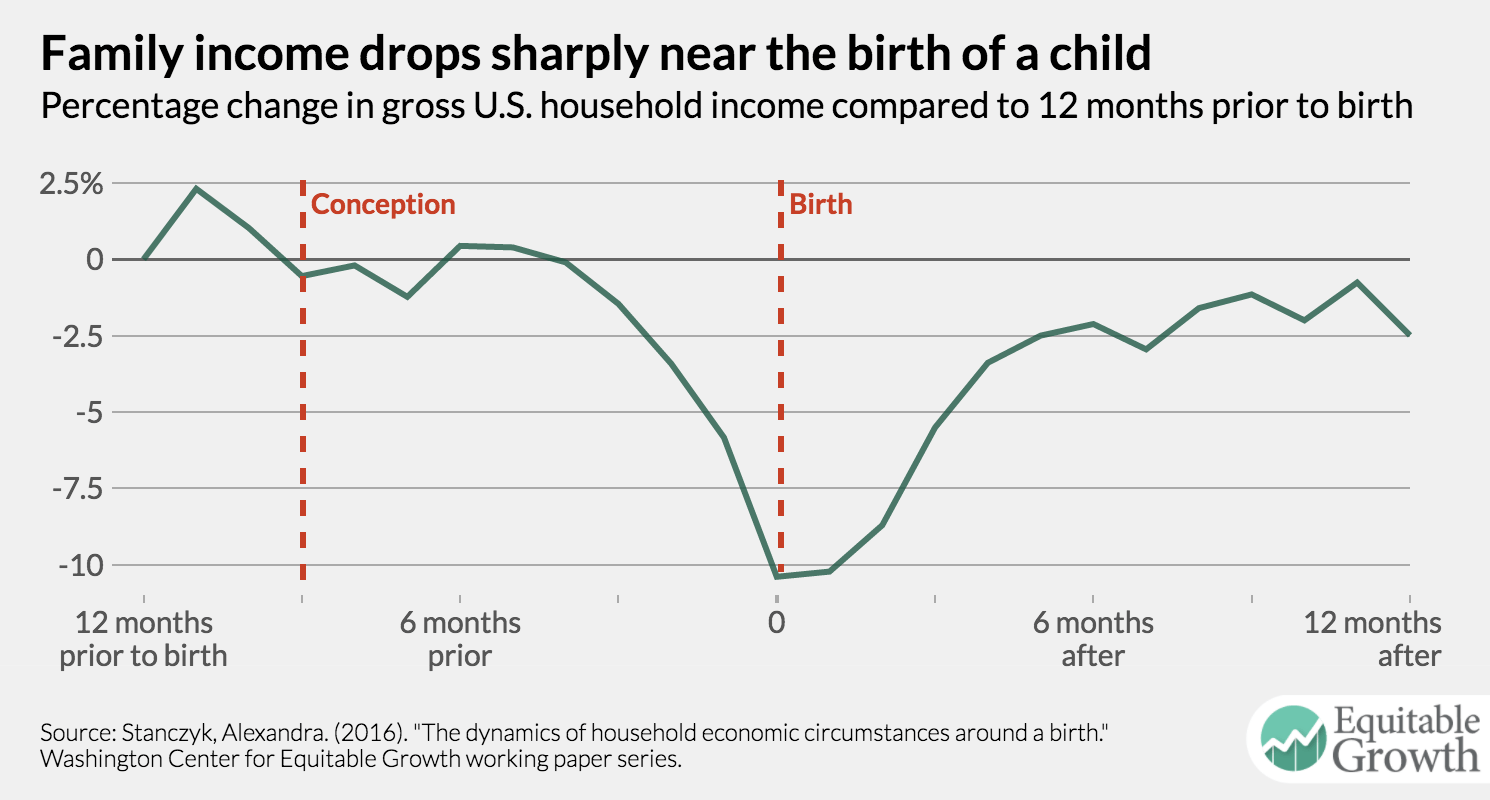

The data show U.S. household income dramatically falls around childbirth

About four months before birth, gross household income—one of Stanczyk’s economic well-being indicators that includes a household’s total income, public program cash transfers, refundable tax credits, and income from other unrelated household adults—declines sharply. In fact, by the time of birth, gross household income is, on average, 10.4 percent below its value just 12 months prior.

2. & 3.

The results hold for different demographic groups

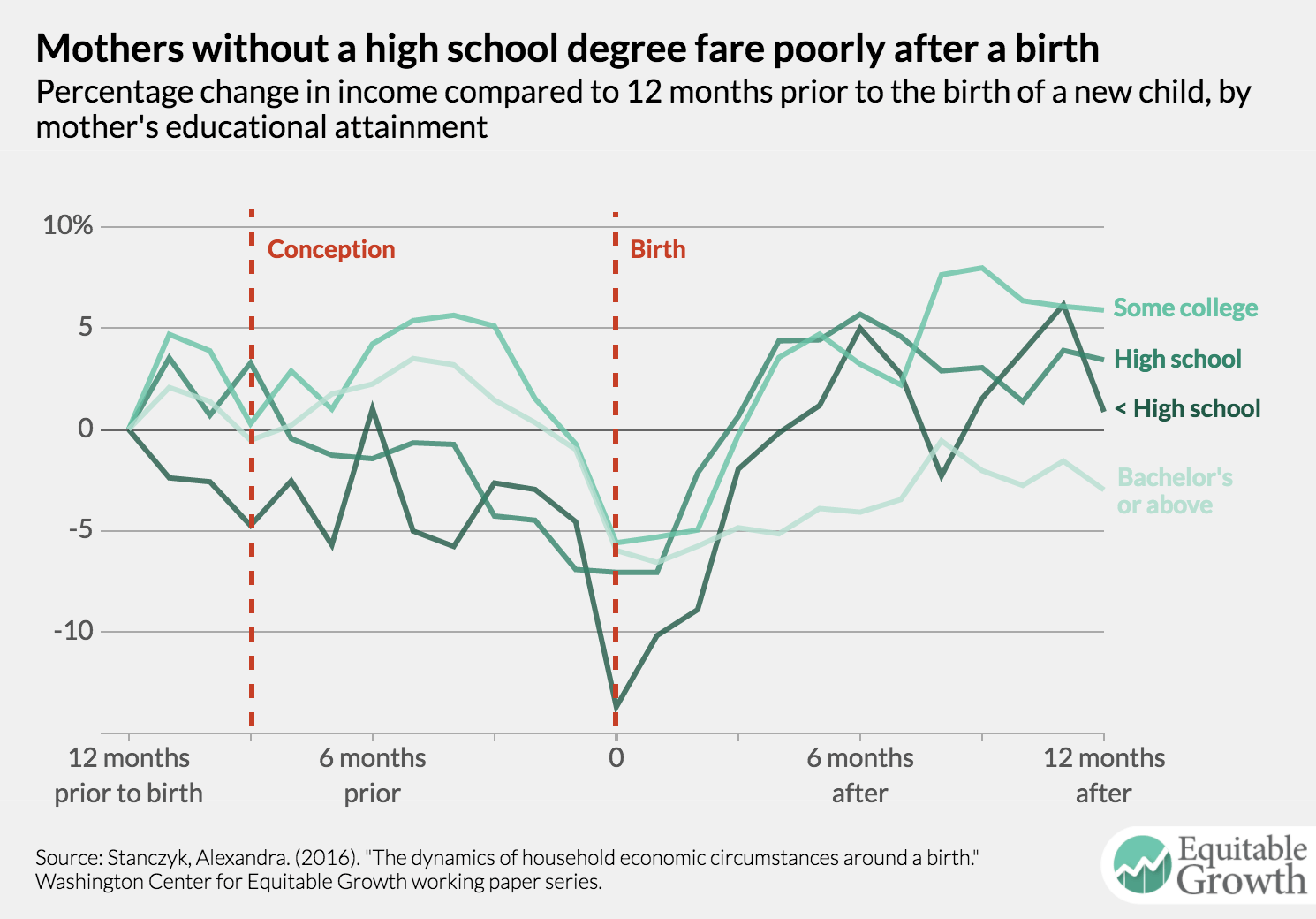

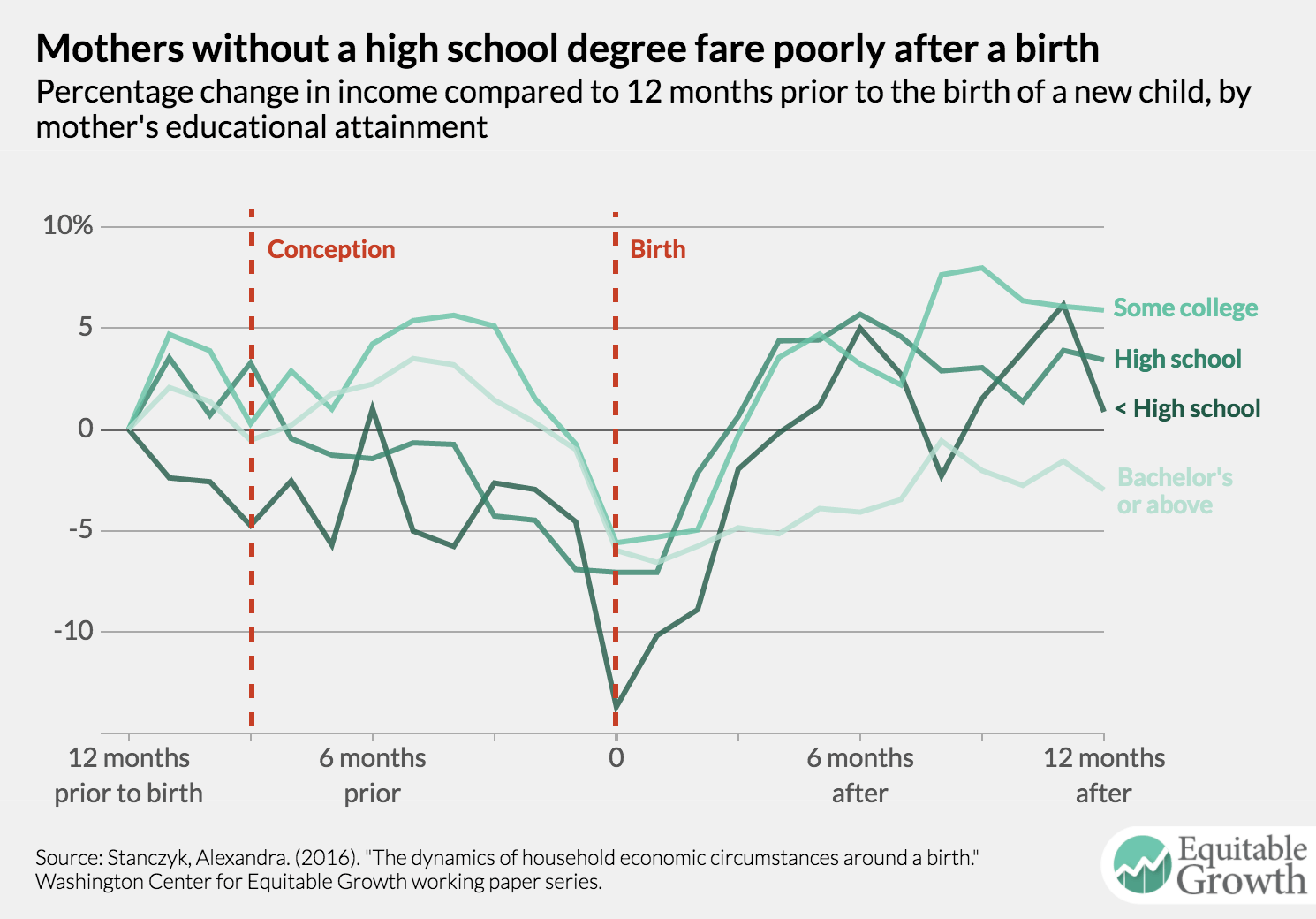

Stanczyk charts that these income shocks around a birth of a child are visible across different demographic groups, too. Take educational attainment: Regardless of a mother’s education level, gross income drops around a birth, but households that have either very high or very low levels of education are hit the hardest.

In households where mothers have a bachelor’s degree or more, income does not fall substantially, but it takes a significant amount of time for it to return to its original levels. The slow recovery may be because better-educated women are more likely to have access to policies that support leave around childbirth or have enough of a financial buffer to remain out of work for extended periods of time. For households where the mother hasn’t completed high school, gross incomes reach as low as 13.7 percent below its initially observed value at the birth month, but quickly return to pre-birth levels. This is in line with other research that shows less-educated women often return to work soon after giving birth because of financial strains and a lack of paid leave policies.

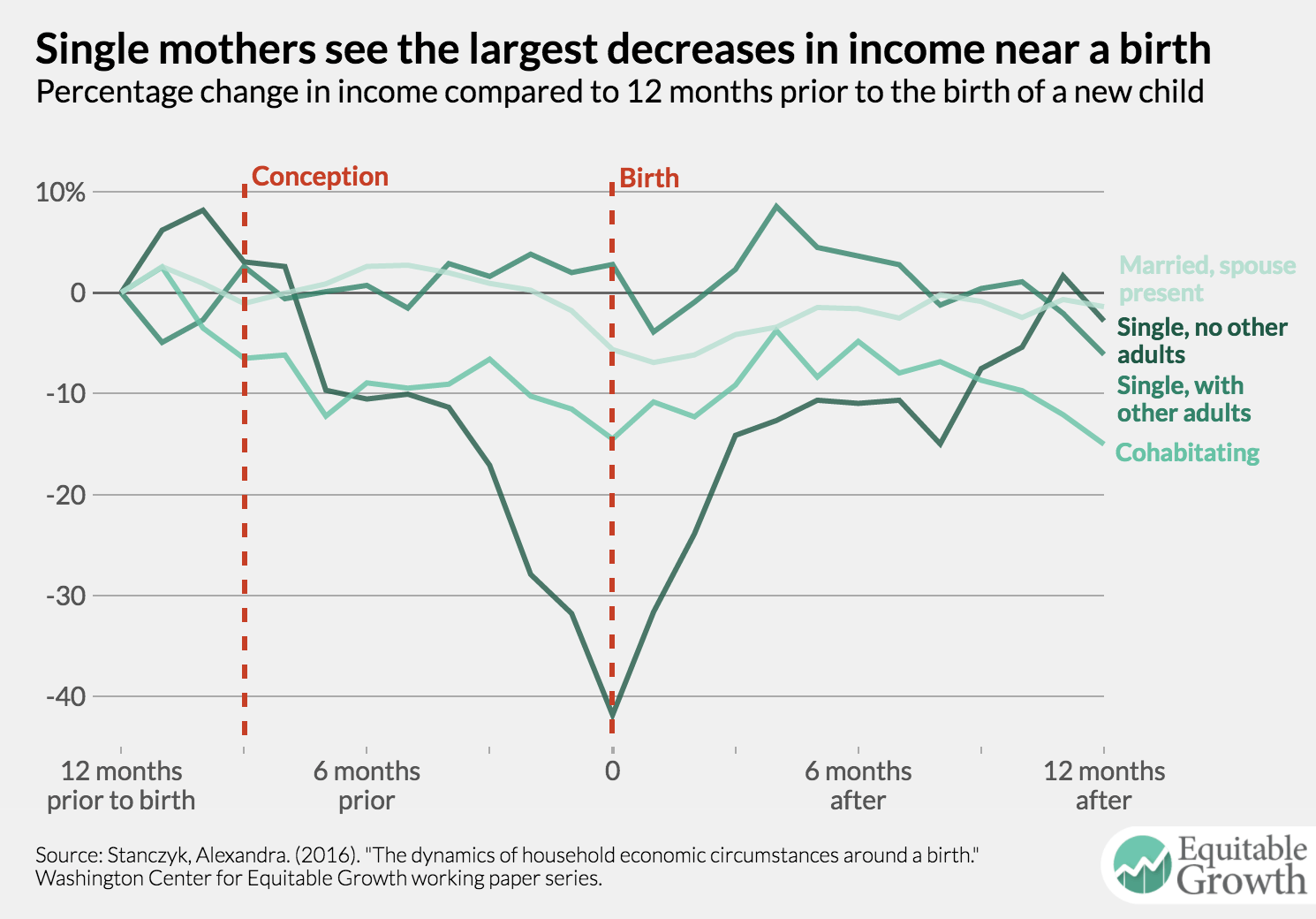

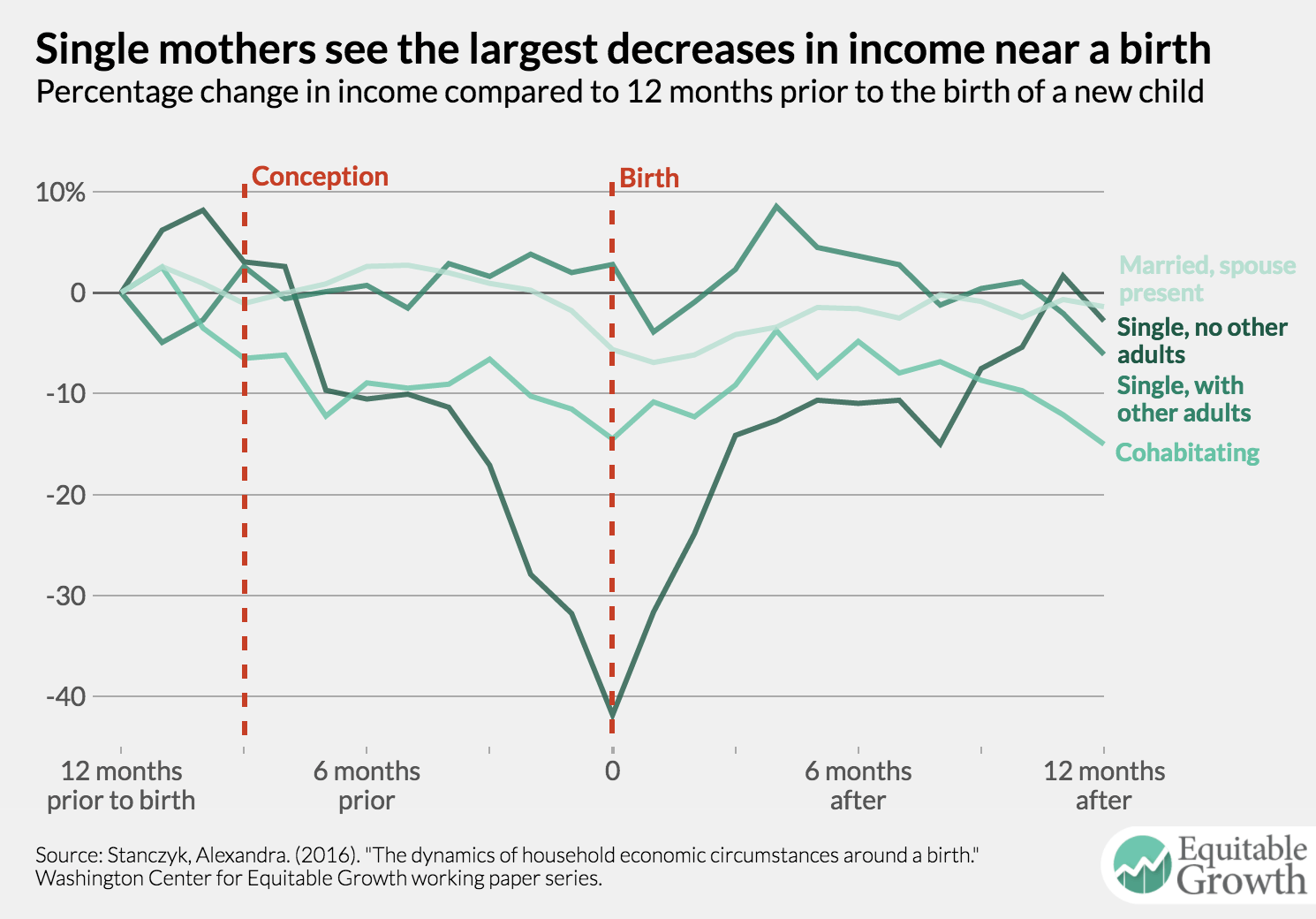

When looking at household structure, Stanczyk finds that households with only a single mother experience the greatest income volatility around a birth.

Shortly after conception, single-mother households see a steep deterioration in their gross income; on average, these households experience a 41.8 percent decrease in their starting income. Similar to households with less-educated mothers, income rapidly increases for these single-mother homes in the months after a birth.

4.

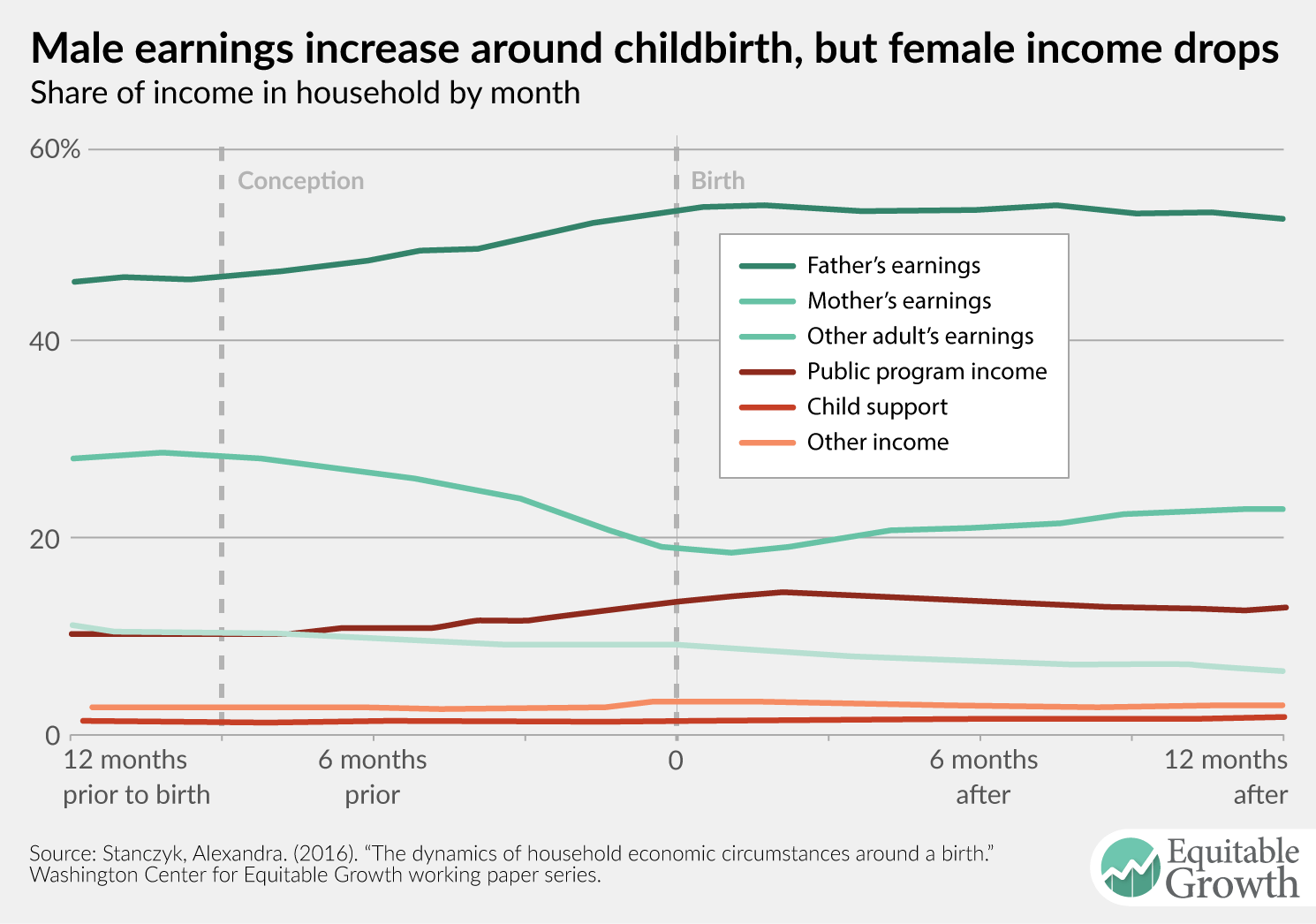

The composition of household income changes around birth, exacerbating the gender wage gap

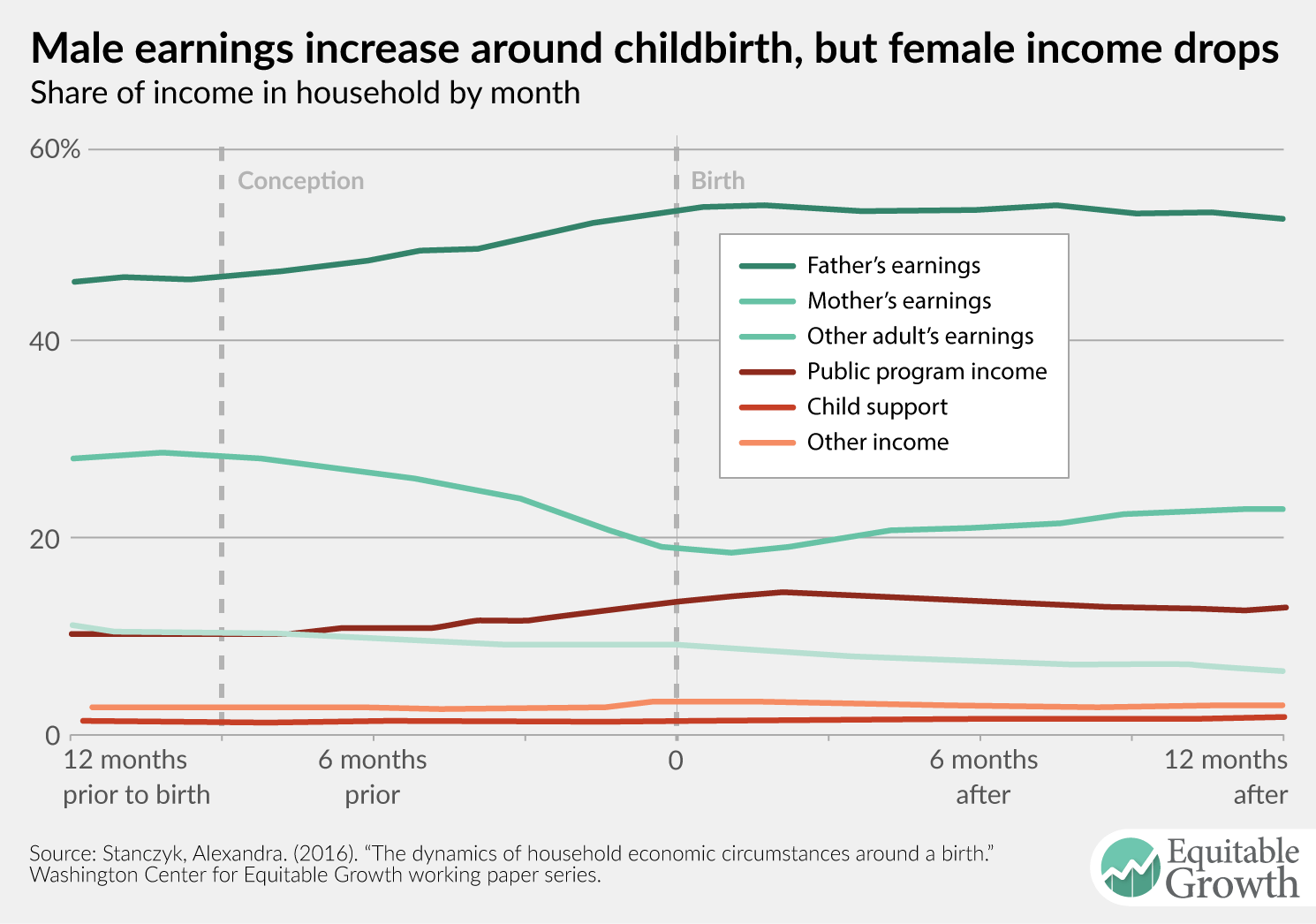

To better explain this financial volatility that families face around childbirth, Stanczyk decomposes gross income into six parts: father’s earnings, mother’s earnings, other household adult’s earnings, income from public programs, income from child support, and other sources of income. It turns out that in the year leading up to birth, the mother’s share of household income sees the largest decreases, while the father’s share of household income increases. In other words, pregnancy and childbirth widens the gender wage gap.

These results may be somewhat unsurprising given that most women in the United States take time off of work around childbirth, and to mitigate these losses to household income, fathers may increase their earnings if they are present. But Stanczyk also shows that families also become more reliant on income from public programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program for Women, Infants, and Children, the Earned Income Tax Credit, or the Child Tax Credit.

Public programs help economic security for new families, but not nearly enough

As vital as these programs already are for household economic well-being around a birth, Stanczyk argues that social safety net programs need to be strengthened.

On one hand, improving the generosity of the programs can reduce sharp changes in household income during the period surrounding childbirth. On the other hand, the effectiveness of these programs may be hampered by when benefits are received. Stanczyk recommends adopting a child benefit policy—a social security cash transfer given to families with children—and implementing paid family leave and childcare subsidies. Altogether, these policies, if enacted equitably, can improve the economic security of households during a critical, and exciting, time.