The U.S. unemployment rate now stands at 4.9 percent, a seemingly healthy level last experienced prior to the Great Recession of 2007-2009. Yet what is not reflected in this statistic is the growing number of Americans who have dropped out of the labor force altogether. Economists are still puzzled by this decline in the so called “labor force participation rate”—meaning the percentage of Americans that either have a job or are actively looking—especially among Americans between the ages of 25 to 54, who are supposed to be at the peak of their working life.

Scholars and policymakers interested in this trend mostly focus on the U.S. labor force’s “guy problem,” but the number of women in the labor force is amid a two-decade-long decline that began just as the cost of childcare began to rise. Are the two trends related? And if so, how big an effect does higher childcare costs have on women’s employment?

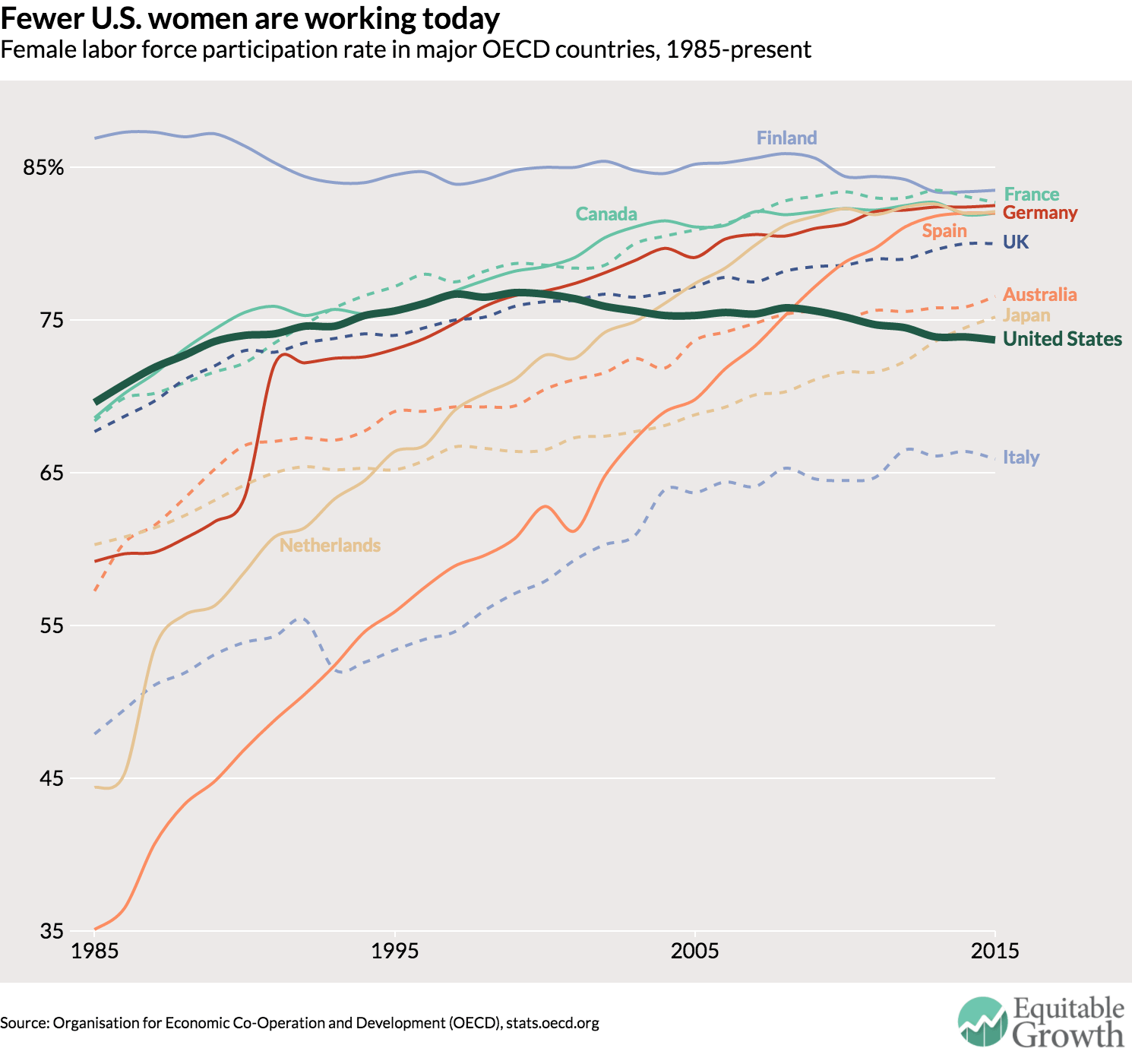

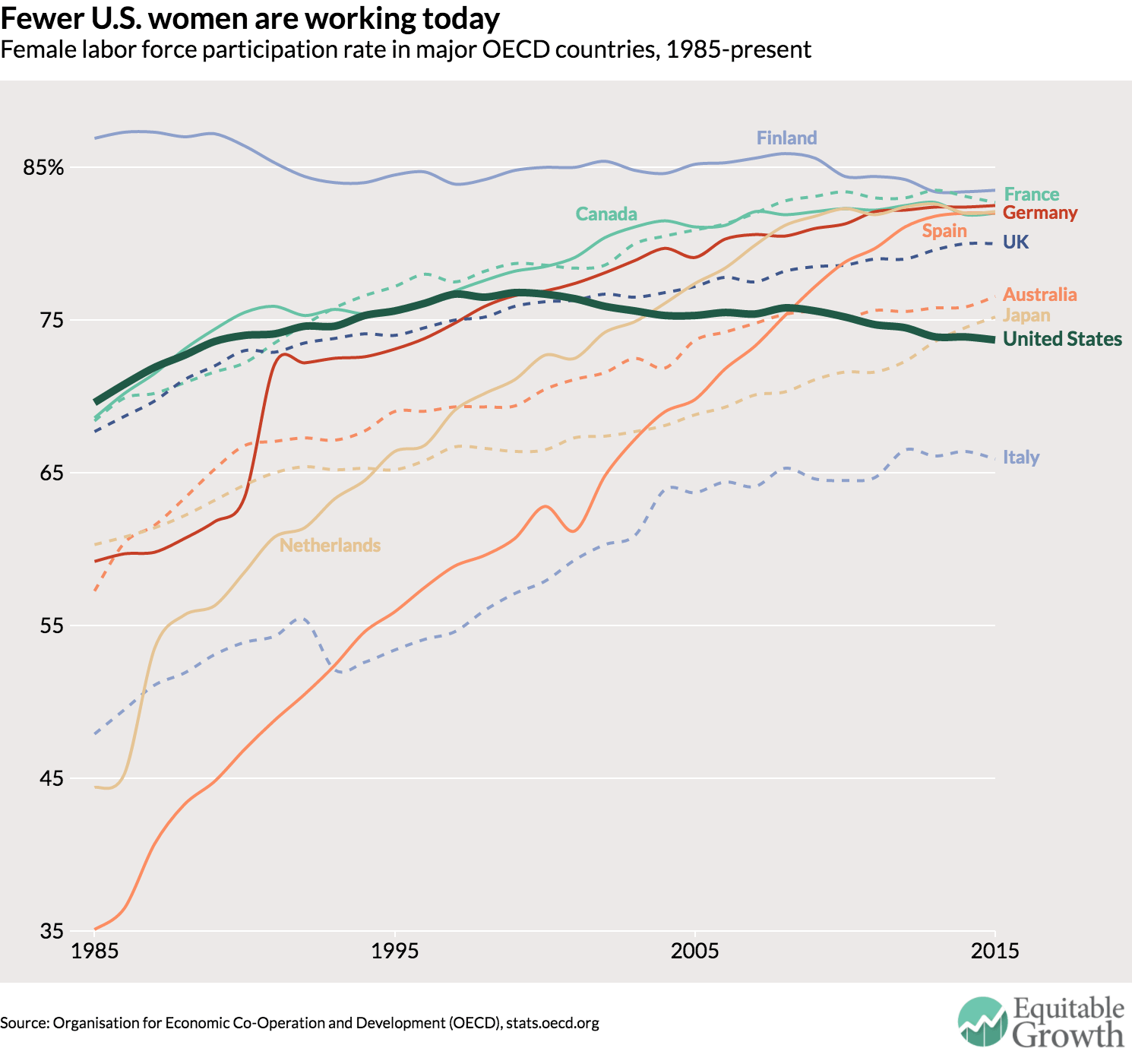

A recently released job market paper by So Kubota, a Ph.D. candidate in economics at Princeton University, attempts to tackle these questions. Kubota looks at women’s employment from 1985 to 2011. At the beginning of this period, women were entering the workforce in droves, and by the early 1990s the United States had one of the highest female labor force participation rates in the world. Today, however, many of our peer countries, economically speaking, have far surpassed the United States in this realm. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

What happened? Research by economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn at Cornell University finds that the United States’ lack of family friendly policies to support women in their prime childbearing and career years explains one-third of the decrease in women’s labor force participation. The U.S. political landscape contrasts with many European countries, which have enacted and expanded policies such as paid parental leave, childcare subsidies, and part-time work entitlements to encourage women’s employment.

Kubota’s work complements Blau and Kahn’s work, and finds that large increases in the costs of childcare in the United States also play a role. Between 1990 and 2010—a period in which wages stagnated for many workers—the hourly cost of childcare rose 32 percent. (Childcare workers did not experience a corresponding rise in wages and today make about 40 percent less than the national median wage.) There are many theories about why costs rose as much as they did, but Kubota suggests that it was largely driven by a series of state and federal policy changes over the same period.

Kubota finds that rising childcare expenditures by families resulted in an estimated five percent decline in total employment of women and a 13 percent decline in the employment of working mothers with children under the age of five. In many ways, these results are unsurprising. Childcare is the single biggest monthly expense for some families (it exceeds the average cost of in-state college tuition in more than half of the states) while one third of parents who use childcare say that it has caused a financial problem for their household.

As prices rose, many parents began to rely less on fee-based childcare, instead seeking out other informal arrangements such as grandparents or other family member. But these kinds of arrangements are less reliable. And when they fall through, women are more likely than men to be the one to pick up the slack.

Kubota points out that his paper examines the effects of rising childcare costs on female labor supply, but adds that “it also has a significant factor on total labor supply.” Among today’s families, work-family conflict is no longer just a “women’s issue.” Women are breadwinners in 40 percent of families, and men are taking on more housework and childcare than ever before (although still significantly less than women). In fact, 60 percent of fathers in dual-earner couples reported work-family conflict.

The drop in the U.S. labor force participation rate among men and women should concern policymakers for several reasons. First of all, it has a considerable impact on U.S. economic performance and growth. And, considering most families now rely on two incomes to stay afloat, more women leaving the workforce threatens family economic security. Women’s long-term earnings and financial well-being also are at risk, reducing their accumulation of long-term savings and the ability to be financially viable in the case of divorce or a partner’s death.

Addressing the growing childcare crisis in the United States as well as helping parents by enacting other work-family supports are critical to helping more women stay in the labor force, bolstering family economic security and ensuring more robust and sustained economic growth.