Scholars have long thought about how our jobs shape our identities both in an out of the workplace. But a new paper shows the extent to which one’s job—or lack thereof—also impacts the roles we assume within our family life. The research, by Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s David Autor, University of Zurich’s David Dorn, and University of California-San Diego’s Gordon Hanson looks at what happens to families in the United States when work disappears, specifically in areas with a high concentration of manufacturing that are hard-hit by trade.

Men and women have both paid the cost economically speaking, but they have reacted differently to their changing fortunes. Whether an affected industry is male-intensive versus female-intensive has a profound effect on local marriage and fertility trends. Traditional marriage patterns are more common in areas where men’s economic status remains superior to women’s, but less so where men’s jobs have taken the largest hit.

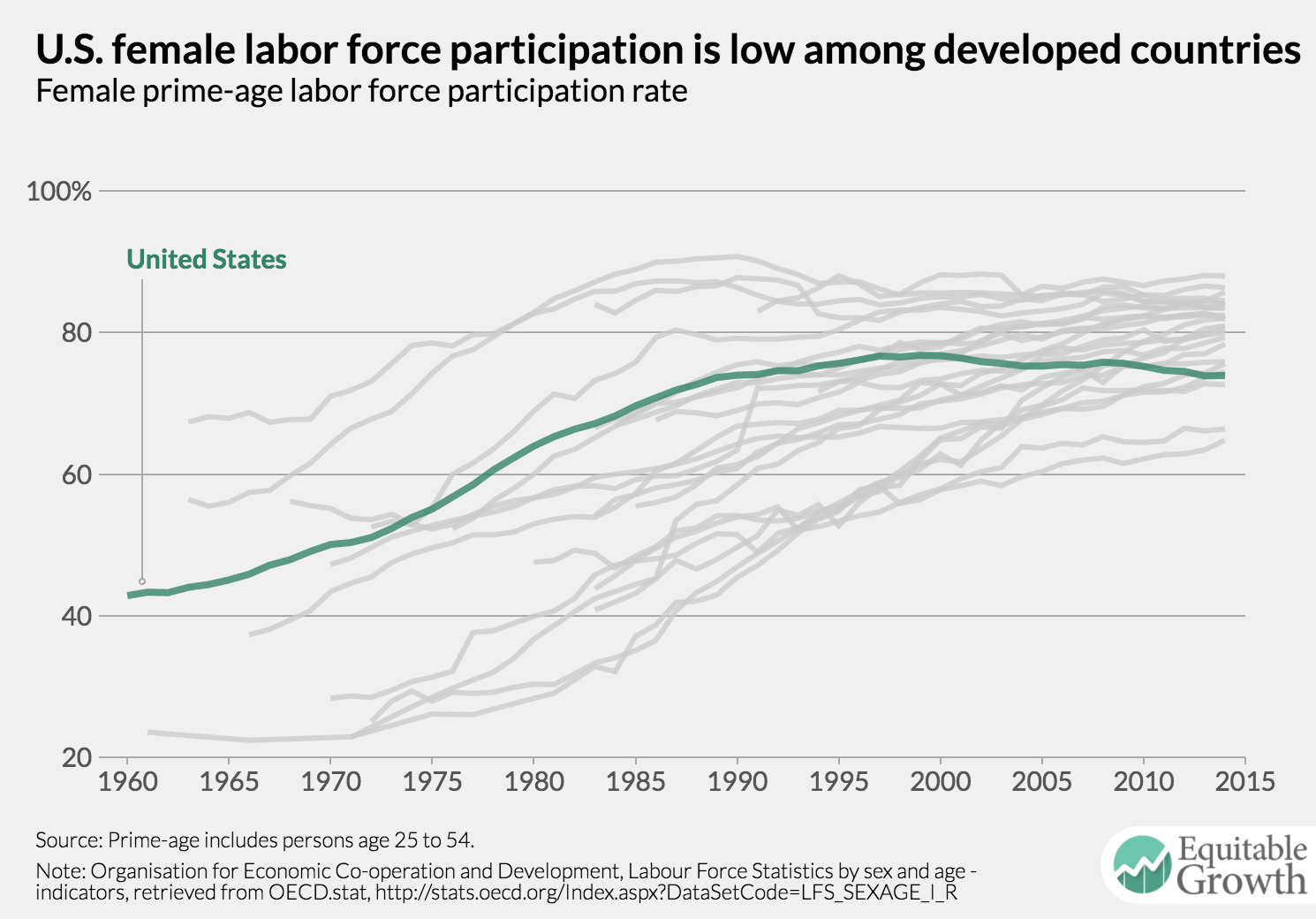

Manufacturing has historically been a “good job” in the sense that it was steady and well-paying for someone without a college degree. Men have always been more likely to hold these jobs, partially due to the perception that “it’s still dirty and dark and dangerous.” Women who do work in manufacturing tend to be concentrated in certain industries, such as textiles, apparels, and leather. In the 1990s, the share of female manufacturing workers peaked at 32 percent and has since fallen, as women-dominant sectors were hit especially hard during the Great Recession.

The gender gap in manufacturing matters because manufacturing jobs tend to pay more—17 percent on average—than non-manufacturing jobs, which contributes to a gender gap in pay. In fact, the male-female gap in annual earnings is much larger in areas in which a large share of adults (men and women) working in manufacturing. In these areas men take home, on average, a much bigger paycheck than their female counterparts.

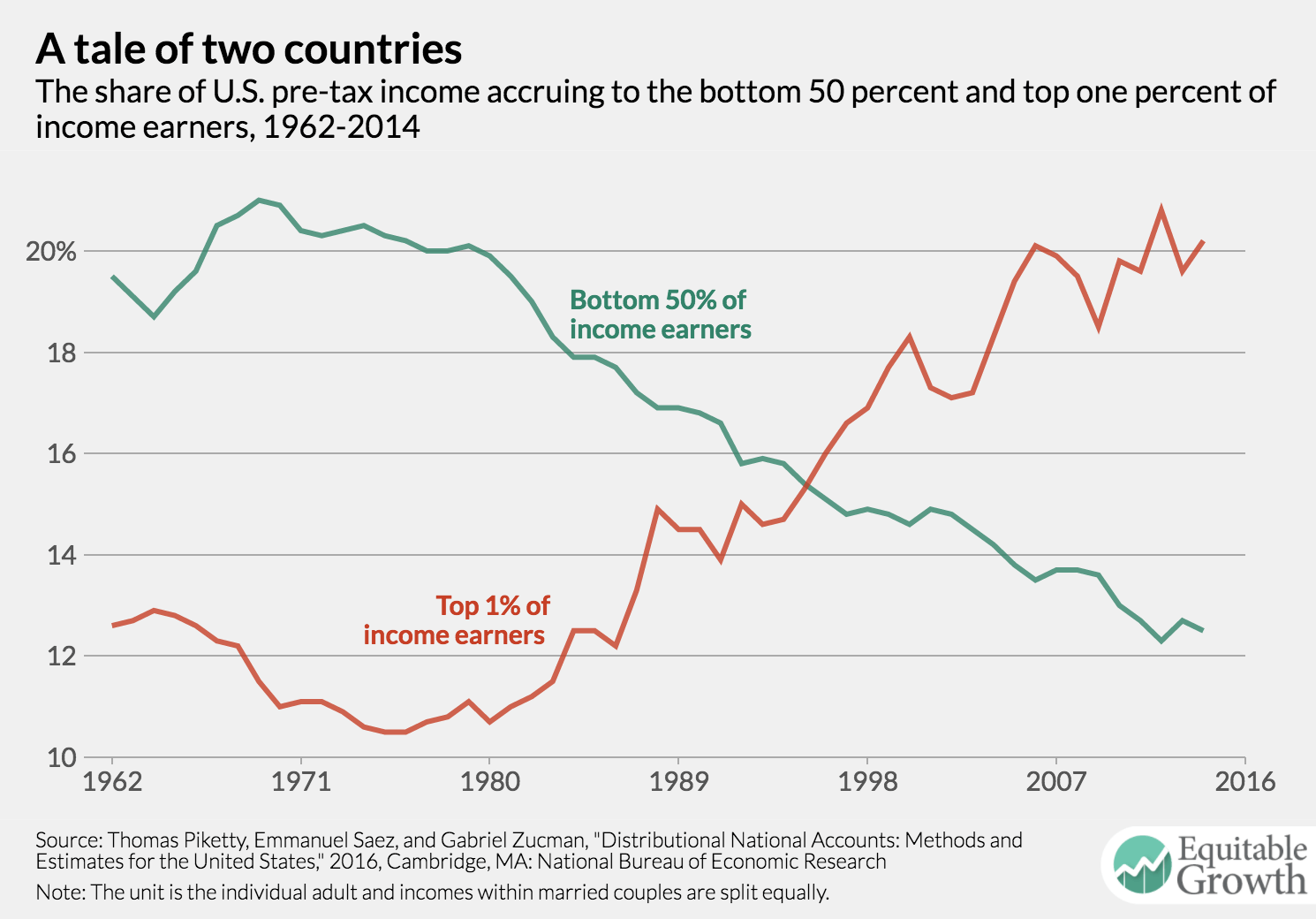

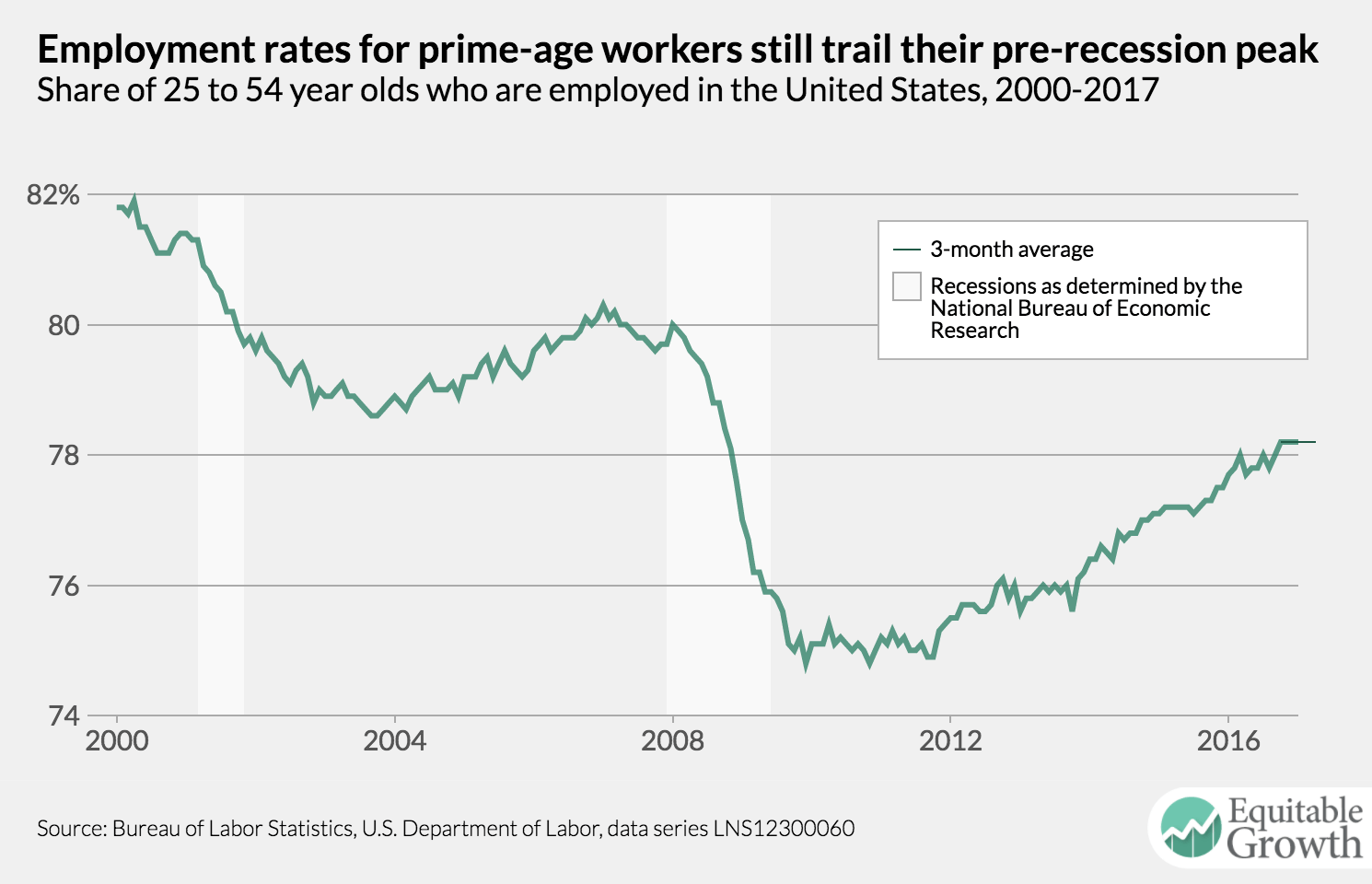

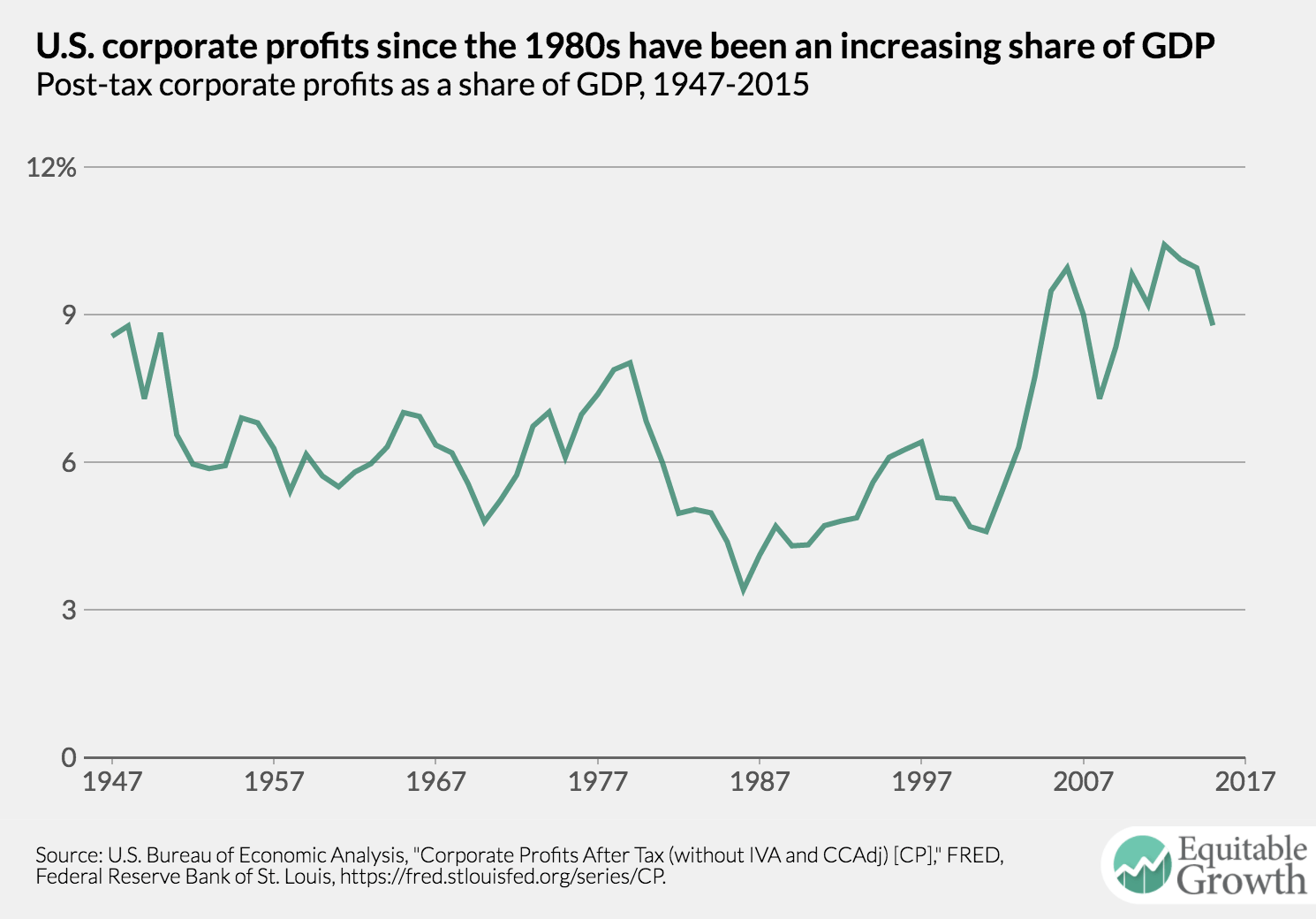

But over the past few decades, manufacturing has been on the decline due to increased competition and trade, leaving many men—and women—out of a job or earning less. But with all the anxiety that’s accompanied this shift, it’s easy to overlook another key trend—growth in the service sector has added more jobs than were lost in manufacturing. These jobs tend to be low-paying, however, which is one reason many men are reluctant to take them, along with the perception that they are too feminine. Whatever the reason, one thing is clear: Manufacturing’s decline has diminished many men’s economic status in comparison to women, especially men in the bottom quarter of the income spectrum.

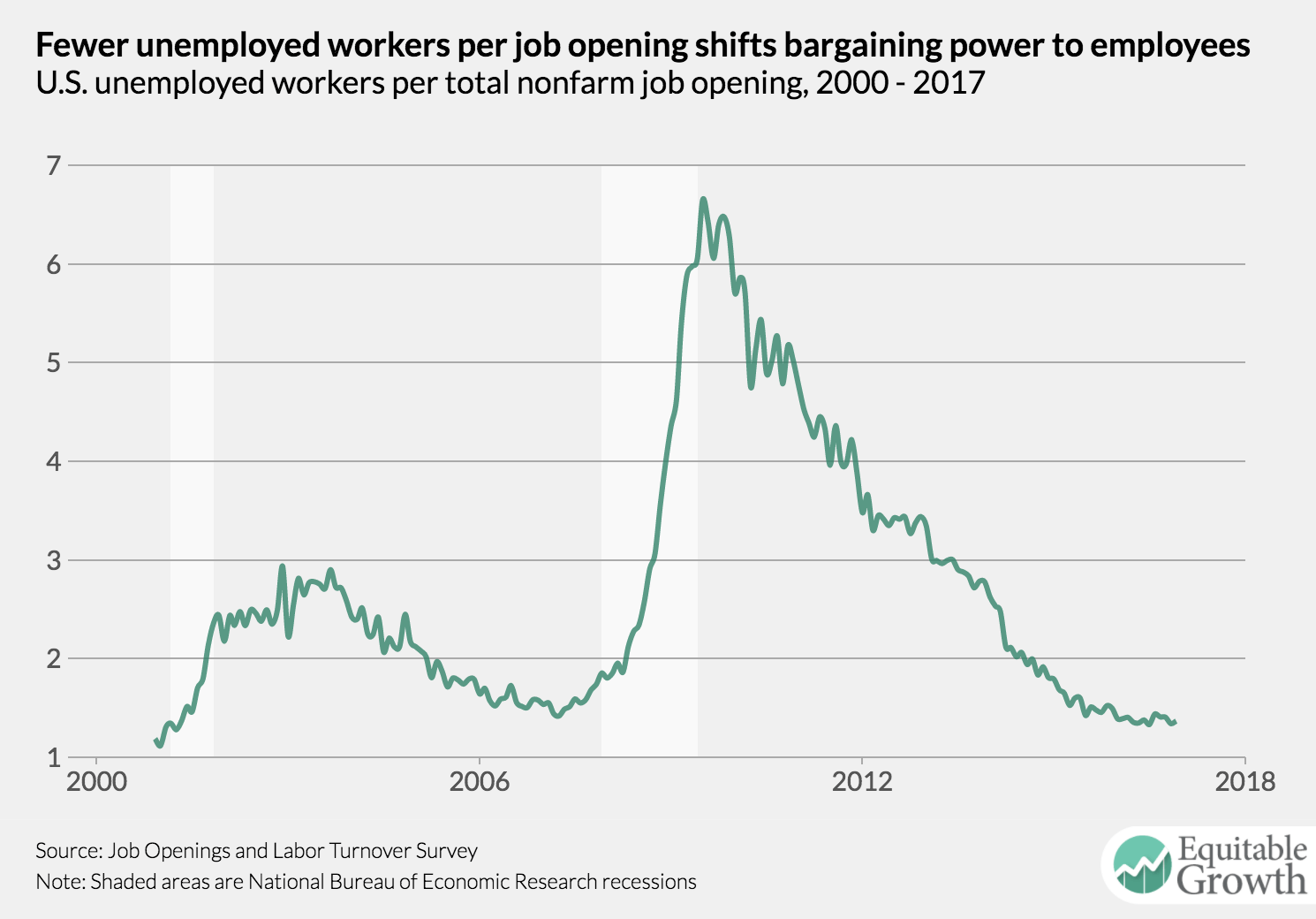

The story of what happens next is familiar. Families struggling to make ends meet. Men dropping out of the labor force all together. An explosion of drug and alcohol use, and, for some, premature death, alongside the rise of incarceration during the same time period. The authors of the paper found that all these phenomena were more prevalent among men in areas where manufacturing declined.

It’s no surprise, then, that entire families would be affected, especially considering that these demographic and social shifts resulted in fewer men overall in these hard-hit regions of the country. Areas that were economically affected most by trade saw a reduction in the number of young adults who are married. These regions also experienced a declining birth rate and a higher rate of babies born to single mothers (and because of that, more child poverty). The authors find that these trends are pervasive across all racial and ethnic groups.

It could be that women are unwilling to legally bind themselves to men who are facing financial, legal, or health problems—or that there are fewer men to marry. Autor and his coauthors believe that these are all valid reasons for the decline in marriage, but also point to research by Marianne Bertrand and Emir Kamenica of University of Chicago, and Jessica Pan of the National University of Singapore. In their paper, they find that marriage becomes less likely between men and women if a women’s income is likely to exceed that of her future husband. The three scholars find that “standard economic models […] cannot account for this pattern. Instead, we argue that gender identity norms play an important role in marriage.”

This hypothesis is further born out by looking at regions that only saw a decline in female-intensive industries, which are fewer in number but have faced enormous upheaval, especially during the Great Recession. Not only did marriages in these areas not decline, but instead marriage rates went up while reducing the number of children who live in single-headed households.

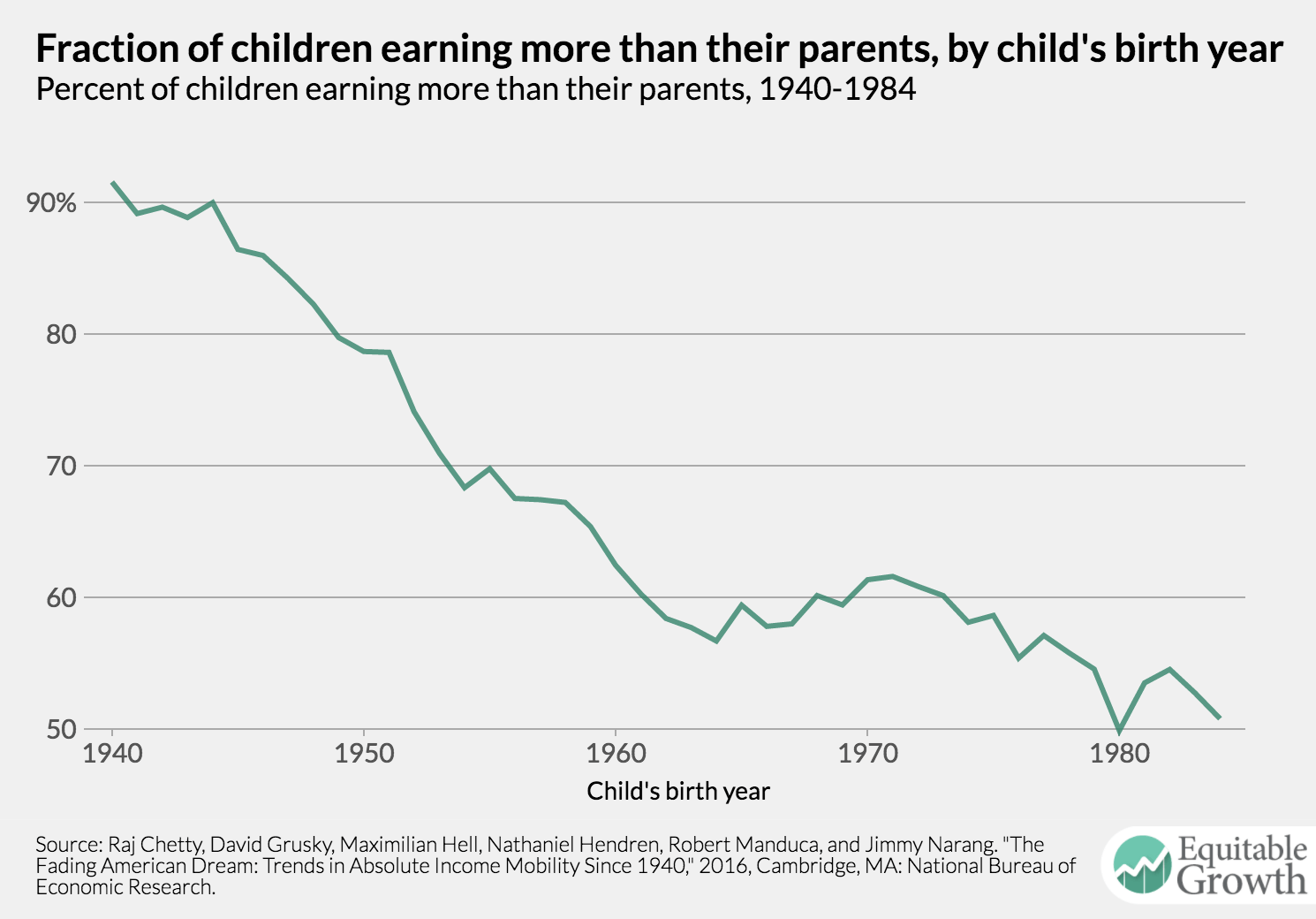

Of course, the overall declines in marriage and single-headed households aren’t driven exclusively by the decline in manufacturing. But this research does speak to how much workers’ identities are tied up with presumed work roles in life, whether that’s one’s job, economic status, or gender. What is clear is that these norms are increasingly costly in the face of a changing economy. The inability of policymakers to help workers adapt is creating a crisis that has a ripple effects for the entire U.S. economy, political system, and prosperity of future generations.