Watching President Trump’s State of the Union address last month and noting his recent budget submission, I was struck by the chasm between the concern he expressed for American families and the paucity of the ideas in that speech and his recent budget for addressing their serious challenges.

“There has never been a better time to start living the American dream,” he said, and referred to our future as “one American family.” But what is his administration doing or proposing for actual American families? And does the research on the challenges they face back these ideas or an alternative path?

It is increasingly difficult for modern families to address day-in and day-out conflicts between their work and home lives. In addition to too-little wage growth for too many workers, there are specific family-related issues that must concern all of us, including workers’ lack of access to paid medical and family leave; the ever-rising cost and limited availability of quality child care; the increasing incidence of work schedule instability; and the pay gap that continues to disadvantage women, particularly women of color.

Considerable research shows that addressing these conflicts between work and life makes the U.S. economy stronger. For example, economists find that weak work-family policies in the U.S. significantly contributed to a decline in women’s labor force participation in recent years, a trend that also harms U.S. economic performance and growth.

Let’s take the above issues one at a time and consider what the President said, what is being done by Congress and the administration, and what could actually help America’s families.

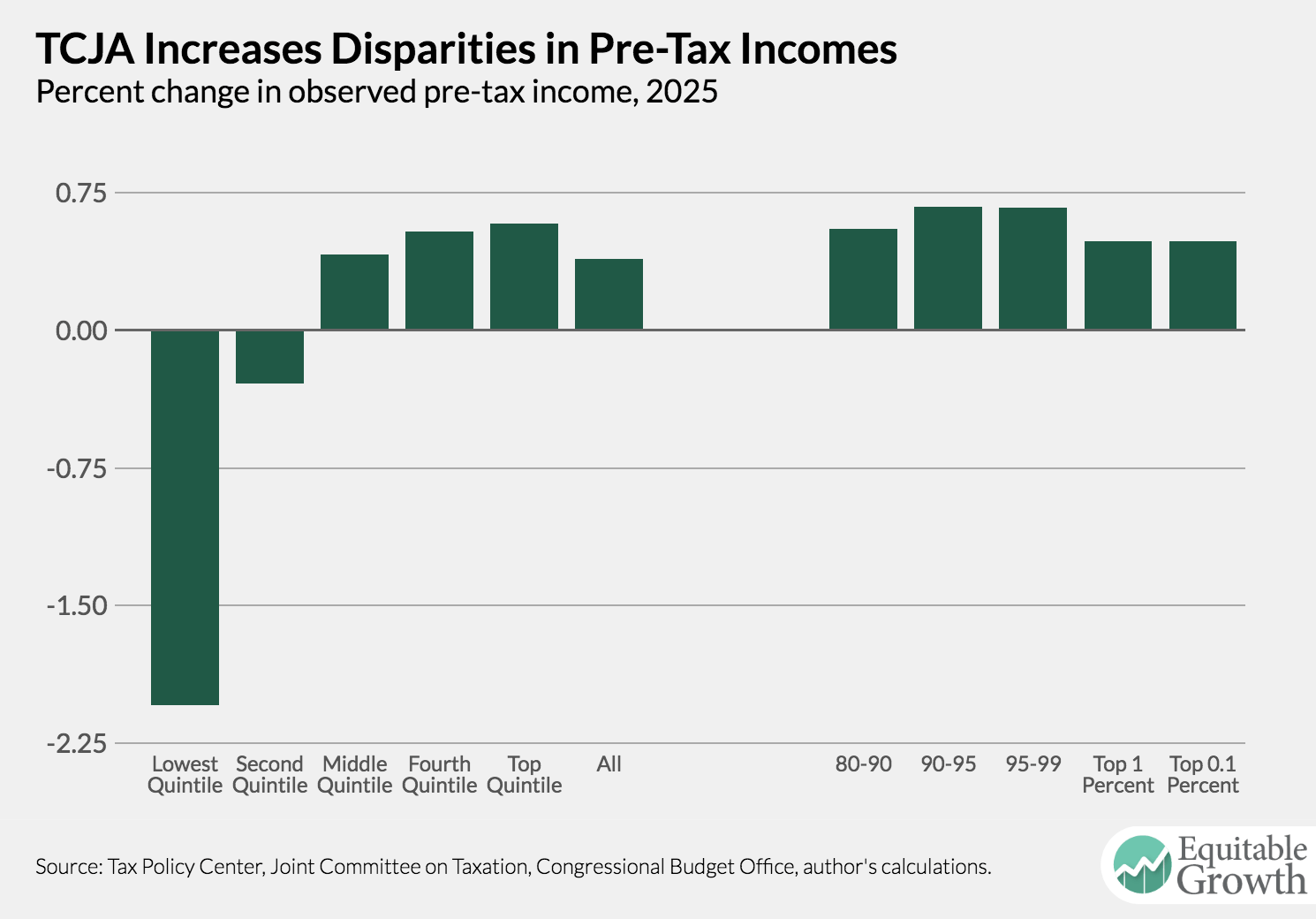

To address the stubbornness of wages, the President is relying mainly on the indirect effects of slashing corporate taxes. But so far, as with past corporate tax cuts, the benefits are going largely to the wealthy in the form of higher dividends and share buy-backs. Very little has trickled down. Splashy press releases aside, it may be that the gradual tightening of the labor market is finally beginning to yield higher wages. We’ll see.

One effect of the tax cuts we have not had to wait for: the Administration is proposing reductions to domestic programs that will mostly affect working families and retirees. Why? To address the budget deficits created by their tax cuts. And then there are regulatory changes like the replacement of the Obama-era rule stating that the tips workers earn belong to them. These workers, mostly women, generally are modest earners, and research shows they generally have very low rates of employer-provided benefits and are twice as likely to live in poverty. Letting them keep their tips—tips that most of us believe we’re giving to the worker for good service—should be noncontroversial, but the Department of Labor is proposing to allow employers to control those tips and distribute them as they wish, even using the tips for capital improvements. It’s no wonder DOL has held back an analysis of how much money this would cost workers.

The modern American family desperately needs a federal paid leave program that gives workers paid time off for the birth or adoption of a child, the illness of a child or other close family member, or the worker’s own serious illness without sacrificing financial security. President Trump mentioned this, his daughter supports it, and his budget includes a barebones plan.

Sadly, that plan is wholly inadequate. It brings to mind the old complaint about a restaurant where the food is terrible – and the portions are so small. The plan takes funds from states’ already-strapped unemployment insurance funds, which should be unacceptable to begin with – to pay for a paid leave program that does nothing for workers with sick children or other family members, or for workers who become seriously ill themselves, and provides an insufficient benefit for a family with a new child.

We should look to the states and adopt what has worked there: a program that utilizes existing social insurance programs (Social Security at the federal level) and is funded by a small payroll tax paid by some combination of employers and workers. Research shows these programs support families and businesses alike. Businesses are able to retain valuable workers instead of losing them permanently because they can’t afford to pay them during their times of need.

Finding affordable, quality childcare is a problem that faces nearly every modern working family. And the cost of quality care could be having a serious impact on the U.S. economy. The current set of federal programs and tax breaks provide important help, but quality, availability, and cost of childcare are still major issues for millions of families and are affecting the U.S. labor supply. Unfortunately, this problem went unmentioned in the State of the Union. There is no shortage of ideas for strengthening the programmatic and tax support we provide to workers facing the childcare dilemma. Now is the time to act.

A growing challenge facing workers is schedule instability – unpredictable work hours that make it difficult to impossible to plan child care and family life. We need to look for ways to protect these workers, while ensuring that companies have a reliable workforce.

An important scheduling issue that the President did not mention and is actually exacerbating is excessive or uncompensated overtime. Fewer and fewer workers are covered by the Federal Labor Standards Act requirement that employers pay time-and-a-half for overtime. The Obama administration sought to restore overtime for millions of workers by increasing the salary employers must pay before they can avoid paying overtime, but the Trump administration killed that rule, thus subjecting millions of workers to continuing undercompensated overtime. These workers, and their families, need the protection the FLSA was meant to provide.

Another significant scheduling issue facing low-wage workers in the service and retail industries in particular is unpredictable schedules. For many of these workers, schedules can change day-to-day, or even hour-to-hour, without warning. New policies should, at a minimum, require that employers, not workers, bear the costs of last-minute shift scheduling decisions, and bar employers from retaliating against workers who express concern about their schedules. This is a growing problem among workers facing serious economic challenges, and we need to make it a high priority.

Finally, the administration rarely discusses the gender pay gap. Women, who make up 51 percent of the U.S. workforce, earn on average 80 percent of what men earn—and women of color tend to earn even less. While research on the causes continues, current U.S. programs, labor laws, and institutions, as suggested above, do not do nearly enough to address the various ways in which women are held back at work. Women are disproportionately affected by the shortcomings of current policies and programs that should help parents balance work and family responsibilities. Boosting women’s economic outcomes by addressing these issues would improve worker productivity and therefore the U.S. economy.

The problems I’ve outlined here are both a reflection of and causes of the growing inequality in our economy and society. Research increasingly shows that inequality is a drag on the economy – so these issues are important to all Americans. I don’t expect this administration, or this Congress, to do a 180-degree turn and begin supporting families and workers. But I hope that we can look forward to these kinds of changes in the future.