New U.S. Treasury Department research shows that it pays to be an S corporation

Businesses that are organized as so-called pass-through entities for tax purposes—meaning their profits show up on the owners’ personal tax returns rather than on an entity-based tax return—pay a lower federal income tax rate than if those businesses were organized as more traditional corporations. That is the clear finding of new research from experts at the U.S. Department of the Treasury, who used actual tax data from a representative sample of so-called S corporations from 2018 through 2021 to study this question. Importantly, the researchers find that these lower tax rates would still be true even if a recently enacted special pass-through tax deduction didn’t exist.

These findings are extremely pertinent to the forthcoming tax debate in the U.S. Congress. In particular, a special tax deduction for pass-through businesses that was enacted in 2017 is set to expire next year. That impending expiration has fueled a lot of ongoing debate over whether traditional C corporations are now paying lower rates than pass-through businesses, especially because the same 2017 tax law dramatically lowered the C-corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent. That law introduced the new deduction for owners of pass-through businesses, also known as Section 199A, partly in response to criticism that such businesses were being disadvantaged by the very large corporate tax cut.

That new deduction expires after next year, while the lower corporate tax rate does not expire. That situation raises the question that Lucas Goodman, Quinton White, and Andrew Whitten, nonpartisan economists who work at the Treasury Department, have now answered: Are S corporations now at a tax disadvantage? Or would they be at a tax disadvantage if the pass-through deduction expired? The answer to both questions, the authors find, is a resounding “no.”

The three co-authors calculated the actual tax rates paid by a representative sample of actual S corporation tax returns, and then recalculated what their taxes would have been under two alternative scenarios. First, they calculate what their taxes would have been had those S corporations instead been C corporations and therefore subject to the ordinary corporate income tax, as well as the tax that C corporation owners pay on dividends and capital gains. Second, they calculate what their tax rate would have been had there been no special pass-through deduction.

What they find is that, overall, S corporations would have paid more if they had been subject to the C-corporate tax instead, and that would have still been true even if they hadn’t had the pass-through deduction. On average, S corporations actually paid an overall effective income tax rate of about 15 percent. That means that of all the income those businesses generated, only about 15 percent went to paying income taxes. Had those same businesses instead been C corporations and subject to the corporate income tax, their average effective tax rate would have been roughly 10 points higher.

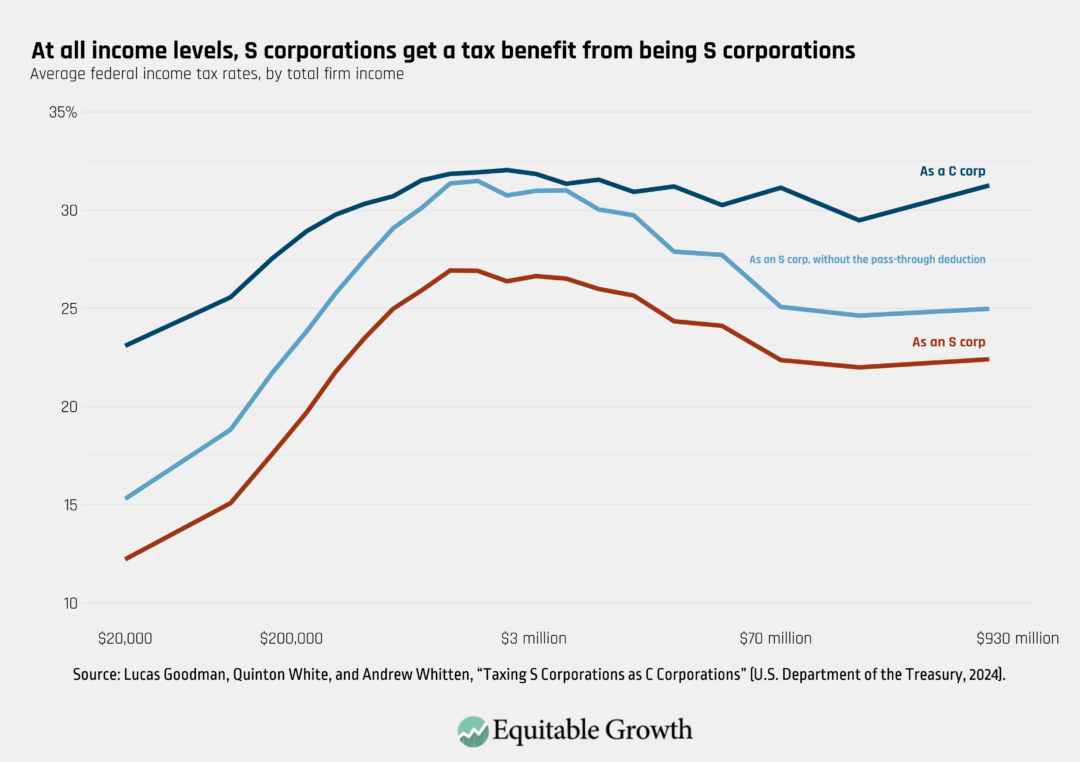

Figure 1

In other words, the average S corporation is getting a 10 percentage point tax benefit from being a pass-through entity—and the special pass-through deduction is only responsible for a part of that tax benefit. In fact, the authors find that without that deduction, the average tax rate for S corporations would be about 19 percent, still 6 points lower than if they were C corporations instead.

Importantly, this finding holds across a wide array of diverse business types and sizes. The average can sometimes mask important variations, but in this case, nearly all S corporations pay lower tax rates, compared to what they would pay if they were C corporations, regardless of their type and size. Whether measuring the size of the business by income or by assets, for example, at every size level, firms paid less because they were S corporations—from very low income and low assets to high income and high assets—and would have still paid less even without the pass-through deduction.

Interestingly, the smallest firms and the largest ones enjoy the biggest tax benefits from being a pass-through entity, while middle-sized firms receive a smaller tax benefit, compared to being organized as a C corporation. This demonstrates that, to the degree that the tax advantages of being a pass-through are intended to help small businesses, those benefits are not very well targeted.

Relatedly, and notably, the U.S. Department of the Treasury study also finds that higher-income business owners are the biggest beneficiaries of the expiring, special pass-through tax deduction. In fact, firms with owners who have an average income of more than $1 million get roughly twice the benefit from the pass-through deduction as firms with owners who have an average income below $100,000. This confirms, with actual tax data, previous analysis suggesting that the pass-through deduction would be extremely regressive—meaning it benefits rich people more than middle-income and low-income people.

The co-authors also find that S corporations paid lower taxes no matter the business sectors in which they compete. Goodman, White, and Whitten separated their sample into six different business sectors to investigate whether the type of business made a difference to their findings. It did not. Across all six sectors, pass-through businesses paid lower tax rates than they would have as C corporations, including under the assumption that the pass-through deduction disappeared.

That’s not to say that there are no examples or situations when S corporations face a higher tax rate than they would have under a more traditional C-corporation structure. The study did find some cases when that occurs or would occur without the pass-through deduction.

For example, the authors separate their sample by the total income of the owners, not just the income of the firm itself. When they looked at the data that way, they find that for owners who had more than $1 million in adjusted gross income, their tax rates are still lower than if their businesses were C corporations, but that they would be slightly higher if the pass-through deductions were gone. That’s not the case for businesses whose owners have an average income of less than $1 million.

The Rise of Pass-Throughs: an Empirical Investigation

September 26, 2023

The promise of equitable and pro-growth tax reform

October 16, 2024

This research makes an important contribution to our understanding of how the tax code treats different kinds of businesses. The authors are clear that there are still many questions to be answered. Their analysis is confined to only one type of pass-through business, for example, and there are other types, including sole proprietorships and partnerships, for which the results may differ. That said, there is other existing research that gives us strong evidence that sole proprietors and partnerships pay even lower tax rates than S corporations do.

The final conclusion is inescapable. Far from disadvantaging S corporations, the current tax code provides a strong incentive to organize as an S corporation instead of a regular C corporation, and it would still do so even if the pass-through deduction never existed. Members of Congress need to take this research into account when debate begins next year over the 2017 tax cuts.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!