Jobs report: November posted weaker-than-expected job gains while visa backlogs could dampen further U.S. employment growth

According to the most recent Employment Situation Summary by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the U.S. economy added 210,000 jobs between mid-October and mid-November—less than half the number of jobs added the previous month and well below economists’ expectations.

Yet, there are also some good news about the health of the U.S. labor market. The prime-age employment-to-population ratio, or the share of 25- to 54-year-olds who have a job, also rose, climbing from 78.3 percent to 78.8 percent. The unemployment rate fell from 4.6 percent to 4.5 percent—now just one percentage point above its pre-recession level.

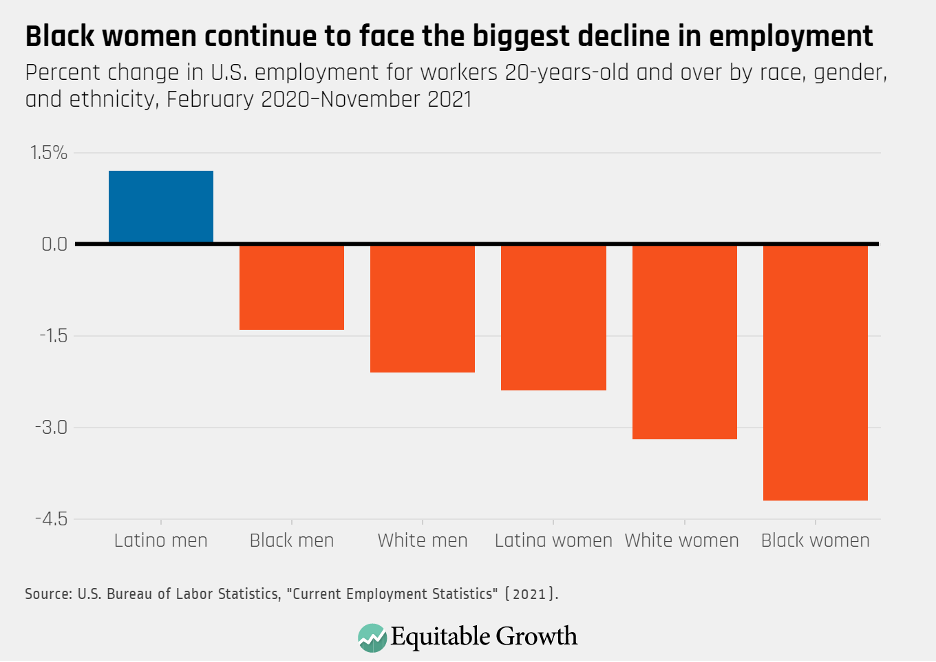

The pace of the recovery has been uneven across demographic groups. For instance, more Latino men were employed last month than in February 2020, but Black women have yet to recover almost half a million jobs to get back to their pre-coronavirus recession employment levels. White women’s employment is 3.2 percent below its pre-recession levels. For Latina women that number is 2.4 percent, for White men 2.1 percent, and for Black men 1.2 percent. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

That last month’s job gains were disappointing at the same time that the unemployment rate experienced a substantial decline is likely a feature of how data for the Jobs report is prepared. The Employment Situation Summary is made up of two separate surveys. The Current Employment Survey—which was developed to measure employment and earnings in nonfarm payrolls—and the Current Population Survey—which was designed to capture labor market status in aggregate and for different demographic groups and which has historically been more optimistic.

The U.S. economy is still at a 3.9 million job deficit compared to February 2020—the start of the sharp but short coronavirus recession. This because many U.S. workers still are fearful of contracting or spreading the coronavirus or are taking on care responsibilities, reassessing career trajectories, or retiring.

Visa backlogs could be holding back U.S. jobs growth

Another factor, however, could be that many jobs are going unfilled because of a slowdown in immigration flows and a massive visa backlog that has left many immigrant workers already in the U.S. without a work permit. Pandemic-driven bureaucratic hurdles explain a big chunk of the current shortfall in visa issuance—in 2020 the U.S. government printed 4 million visas, a 4.7 million decline with respect to 2019. Yet, the issuance of employment-based visas as well as immigration inflows more generally started declining before the onset of the coronavirus crisis.

An analysis by The Washington Post finds, for instance, that the growth in the country’s immigrant population began to slow down during president Trump’s administration. The reporting finds that if the foreign-born population in the United States had followed its pre-2019 trend, then there would have been an additional 2.4 million immigrants living in the country, many of whom would have also been looking for work.

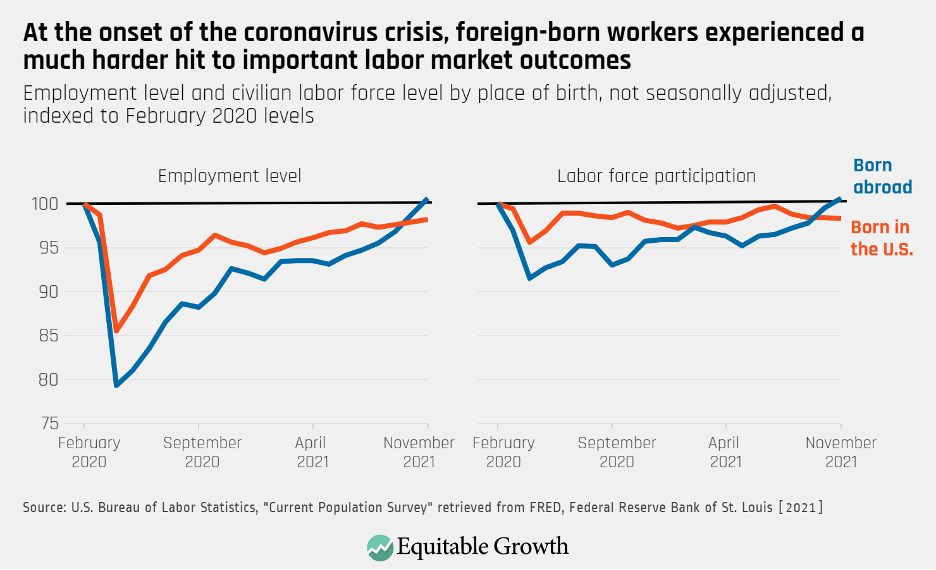

At the same time, foreign-born workers’ labor force participation and employment are now back to their pre-pandemic levels. This is the case even amid plenty of reports of businesses losing much-needed workers due to visa-related issues.

In 2020, foreign-born workers in general and foreign-born women workers in particular suffered much worse labor market outcomes than native-born workers, with official data showing that both the labor force participation and employment levels of those born outside of the country saw a sharper decline. Despite representing only 17 percent of the U.S. workforce, for instance, foreign-born workers accounted for 40 percent of all the workers who stopped participating in the U.S. labor force from 2019 to 2020.

Initially, foreign-born workers also experienced a slower bounce back. But since this past October, foreign-born workers have actually surpassed their native-born counterparts in terms of their recovery in employment and labor force participation. In November, the number of employed workers born abroad reached its pre-pandemic level, while there are still 2.3 million fewer native-born workers. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

This is not an unusual trend. What economist Huanan Xu at the University of Indiana calls a “first fired and first hired pattern” has been a feature of the U.S. labor market at least since the late 1990s, indicating that immigrant workers are both more likely to be fired first as the economy contracts and to be hired first as it recovers. Xu suggests that discrimination and disadvantages in terms of educational credentials might drive the “first fired” phenomenon, while disproportionately large income shortfalls and lack of access to government supports are likely behind the “first-hired” trend.

With monthly quits continuing to break past records, employers reporting struggling to hire workers, and the labor market facing a 3.9 million job shortfall with respect to February 2020, it is essential that the U.S. government addresses the administrative bottlenecks that are keeping millions of immigrants who want and are able to work from doing so.

Steps needed to break the visa logjam and boost U.S. employment and productivity

The Biden administration is taking some initial steps in the right direction. Though it does not set up a path to citizenship, the Build Back Better Act includes immigration provisions that would provide temporary work authorizations and deportation protections for many undocumented workers and their families living in the United States. The bill also includes provisions that would address the massive green card and employment-based visa backlog. In addition, the legislation would appropriate additional funds for the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services to increase capacity and reduce processing times.

The economic evidence behind 10 policies in the Build Back Better Act

November 24, 2021

Equitable Growth’s Jobs Day Graphs: November 2021 Report Edition

December 3, 2021

Policymakers and labor enforcement agencies can also take action to make sure immigrant workers have access to good working conditions. Research by Janice Fine, Jenn Round, and Hana Shepherd of Rutgers University and Daniel Galvin of Northwestern University shows that immigrant workers—and women immigrant workers in particular—are especially likely to experience wage theft, and even more so during recessions. It is therefore essential to ramp up the enforcement of labor standards by targeting some of the most troublesome industries and increasing the cost of noncompliance.

Policymakers also need to ensure that income support benefits are both sufficient and available for some of the workers who need them the most. As such, another important step is to expand benefit eligibility for programs such as Unemployment Insurance to undocumented workers and temporary workers.

Immigrant workers and families make the country’s economy more dynamic, represent a disproportionately large share of the essential workforce, and boost demand for U.S. consumer goods. For this recovery to be complete and broadly shared, immigrant workers need to have access to the country’s labor protections and social insurance programs, as well as to good-quality jobs.