How the economic and political geography of the United States fuels right-wing populism—and what the Democratic Party can do about it

Overview

In wealthy nations around the world, the rise of the knowledge economy has increased political and economic divides that fuel right-wing populism. These divides generally have a strong geographic dimension, and the United States is no exception. Dense metro locales—advantaged in the knowledge economy—have shifted toward the Democratic Party. More sparsely populated nonmetro places—disadvantaged by this profound economic transformation—have shifted toward the Republican Party.

This growing geospatial divide mirrors and motivates many others, cleaving voters across lines of education, occupation, race, ethnicity, religion, age, and immigration status. It divides those who welcome a global knowledge economy and increased social diversity from those who feel threatened by them. In turn, this divide fuels the two political parties’ increasingly distinct appeals, strategies, and orientations toward democracy.

Many of these trends mirror shifts taking place in other affluent democracies. Yet the United States is distinctive in three fundamental respects. First, the U.S. system of representation is both highly territorial and biased in favor of nonmetro places, most starkly in the U.S. Senate. Second, the United States has an extremely rigid two-party system—an unusual feature that has enabled the remarkable right-wing takeover of the Republican Party. Finally, the large role of money in U.S. politics creates a powerful pull toward the interests of economic elites that has affected the two parties differently. These three factors have greatly intensified educational and geospatial polarization and encouraged culturally grounded conflict.

In particular, America’s version of right-wing populism is far more “plutocratic” than its counterparts abroad.1 Viewed alongside right-wing populist parties in other rich democracies, the Republican Party’s revanchist racial and cultural appeals and “anti-system” attacks on government are familiar. Its aggressively inegalitarian and deregulatory policy stances are not. These economic stances are to the right not just of typical right-wing populist parties, but also of typical Republican voters. The result is an even greater incentive for the party to foster affective “us-versus-them” divisions over race and culture—even as it cloaks its economic policies in similar terms, such as attacks on foreign countries, lazy government workers, and an undeserving racialized poor.2

We have called the Janus-faced effects of the knowledge economy the “density paradox.”3 The paradox is that while density enhances economic productivity in America’s transformed political economy, it is bad for electoral representation in the nation’s territorially based electoral system. To win durable governing power, Democrats need to gain and retain the allegiance of voters outside of metropolitan America, including in places unsettled by the transition from industrial to knowledge production.

Former President Joe Biden and congressional Democrats entered office in January 2021 seeking to tackle both sides of the density paradox. Strategic investments would boost prosperity in deindustrialized and nonmetro America; enhanced labor power would ensure this prosperity reached workers without a college degree. The idea was that workers who felt that they and their communities were more economically secure would be less vulnerable to right-wing populist appeals, and organized labor would help create alternative identities for populations who might otherwise find these appeals convincing. This was the promise of Biden’s “deliverism”—desirable policy would lead to Democratic power-building.

During the Biden administration, major new investments were launched through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act, CHIPS and Science Act, and Inflation Reduction Act. Many of them flowed to nonmetro America. Between 2021 and late 2024, red counties received more than 73 percent of announced private strategic-sector investments—more than twice their share of economic output.4 These policies, alongside a vigorous fiscal response to the COVID-19 pandemic, fueled a faster recovery in the United States than seen in other rich countries—and lower-wage workers and slower-growth regions benefited. Coming out of the pandemic, the most distressed U.S. counties experienced increased job growth, particularly in strategic sectors.

Yet the hopes for “deliverism” were dashed in the 2024 general election. Democrats did not gain ground in nonmetro America, nor among White working-class voters, and a right-wing populist party seized power. What happened, and what lessons should be taken for the future?

In this essay, we first describe the shifting coalitional bases of America’s two major parties and how they are related to political-economic geography. Then, we consider how this has fed into the transformation of the Republican Party and the rise of plutocratic populism. Finally, we examine the economic and political effects of Democrats’ response during the Biden administration, focusing on their implications for future political and policy strategies to reduce regional inequalities and blunt the effectiveness of right-wing populism.

The density divide and U.S. right-wing populism

The Democratic and Republican parties look very different than they did even a decade ago. In two key respects, however, they have changed in parallel. First, both parties have become cross-class coalitions based on shared geography, as well as shared identities. Second, this geographic clustering has produced powerful feedback loops that have exacerbated us-versus-them polarization. These feedback effects, however, have had the most profound impact on the Republican Party.

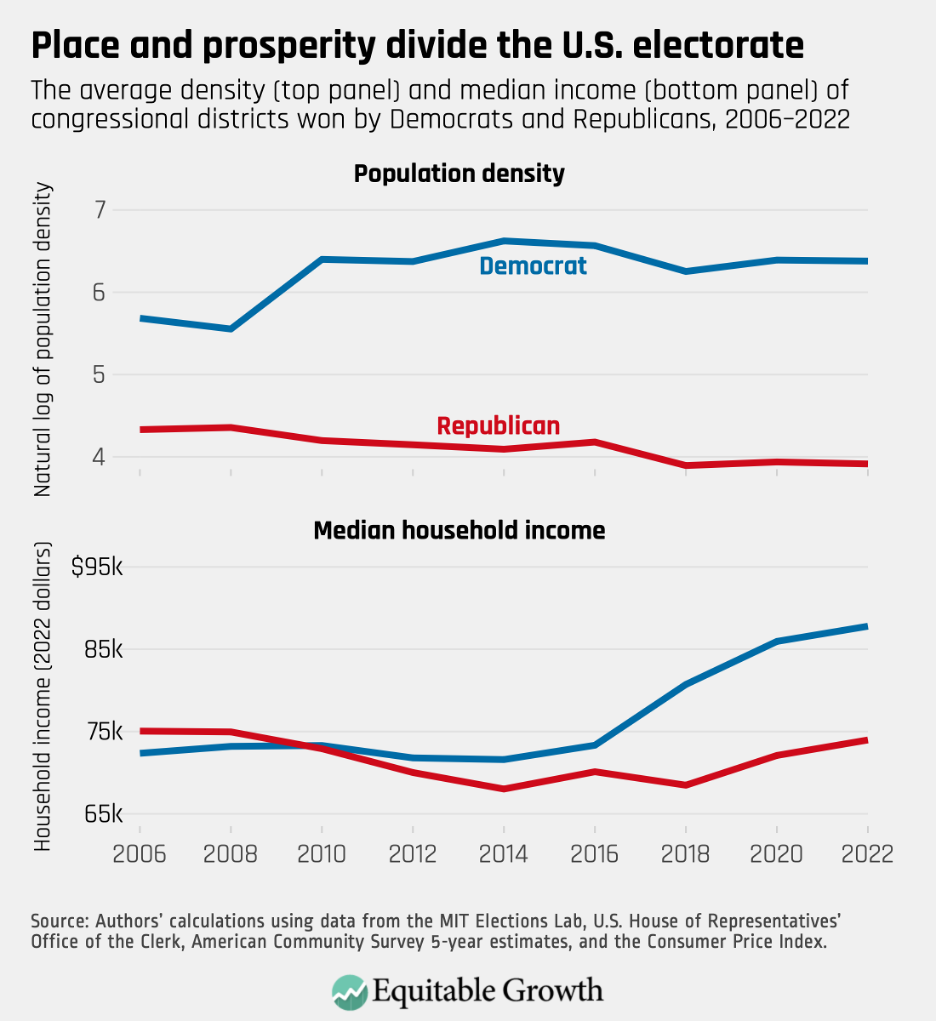

Figure 1 tells the story of intensifying place-based divergence. It shows the average density (top panel) and median income (bottom panel) of congressional districts won by Democrats and Republicans.5 As the figure shows, Democratic congressional districts have become denser and higher-income, while the reverse is true for Republicans. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

While these results go only through 2022, the 2024 election did not change the trends. Democrats did lose ground in metro districts at the presidential level, yet 2024 saw continuing divergence in the characteristics of districts won by each party. And notwithstanding the fall-off in the Democratic presidential vote share in metro areas in 2024 (mostly driven by reduced turnout), nonmetro areas continued to shift away from the party.

The places where Democrats dominate elections are generally both denser and more prosperous than the rest of the United States. They are also highly unequal. The Democrats’ multiracial coalition therefore includes both sides of the widening U.S. economic divide. So, too, does the Republican coalition, which represents many of the poorest regions of the country but has its own affluent voters, as well as a significant subset of the superrich who make outsized investments in the party.

Place-based party divisions, in turn, drive powerful feedback loops. Given winner-take-all elections, a polarized partisan map magnifies the effect of relatively small party edges and encourages both parties to accentuate appeals that map onto the economic and cultural divisions that cleave these places from each other.6 The decline of competitive seats makes intra-party primary challenges more important, reinforcing this polarization.

Finally, social media and legacy media intensify this division by creating within-party echo chambers based on national party divisions, rather than local issues. Gone are the days when particular states, House districts, or even state legislative districts featured ticket-splitting or fostered their own regional party brand. Geographically, it is polarization all the way down.

Asymmetric polarization

For at least four reasons, these forces have had more disruptive effects on the right than the left. First, the Republican Party is advantaged by the territorially based electoral and governing institutions in the United States, which reward parties not just for winning majorities but for winning majorities in particular places. As a result, Republicans have had a built-in edge in the U.S. Senate and, to a lesser extent, the Electoral College and the U.S. House of Representatives. Notably, Republicans have not represented states containing a majority of the nation’s population since the 1990s, while frequently garnering a majority of U.S. Senate seats.

Moreover, the bias is growing as the split-ticket voting that kept Democrats competitive in less populous states has disappeared. Meanwhile, the concentration of Democratic voters in metro areas hinders the translation of votes into seats in both the U.S. House and in statehouse elections—a disadvantage reinforced by aggressive Republican gerrymandering. An important consequence is that Republicans have greater electoral running room to take more extreme stances.

Second, the Republican Party’s voting base is more homogenous. Even with the shift of younger voters and working-class Latinos and Black men toward the party, Republican voters are disproportionately White, working class (with less than a college degree), conservative Christian, and in their mid-40s or older. Democratic voters, by contrast, are more demographically and ideologically diverse.

Third, compared with other parts of the media environment, right-wing media and social media are more influential, extreme, and insulated. Beyond the well-documented influence of Fox News, the online media environment—YouTube, Rumble, Twitch, Kick, Spotify, Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok—is dominated by right-leaning shows, which create powerful feedback loops influencing not only voters but also candidates and elected officials.7

Finally, the intense organized groups associated with the Republican Party—the religious right, gun rights activists, backlash-oriented advocacy groups, and deep-pocketed donors aligned with them—have invested more and more effectively in policing Republican moderation, including through primary challenges.

The result is a vicious cycle of growing extremism that now threatens U.S. democracy itself. Hailing from safe districts and states, where primary challenges are the greatest threat, Republican officials in the U.S. Congress have little incentive to challenge executive overreach and defend the authority of the legislature. Meanwhile, leaders of solidly red states add to this threat by undermining voting rights, aggressively gerrymandering to reduce electoral accountability, and pursuing partisan policies that reflect national party priorities rather than their states’ distinctive economic interests and citizen preferences.

The rural health crisis in red states is what happens when party priorities outweigh popular preferences. As public health professor Michael Shepherd and his colleagues argue, the Republican party has been able to pursue policies unpopular among—and indeed harmful to—its own constituents because it has effectively blamed Democrats and the federal government and because it has successfully elevated culture-war issues.8 As Republicans in Congress hurtle toward major Medicaid cutbacks to finance tax cuts mostly favorable to the affluent, the party’s combination of plutocratic policy priorities and right-wing populist rhetoric remain on full display.

Plutocratic populism 1.0 and 2.0

We describe this dangerous amalgam as “plutocratic populism.”9 Put crudely, Republicans have mobilized voters outside of metro areas with appeals animated by religious, racial, and anti-immigrant backlash—the rhetorical fare of right-wing populism worldwide—while the policies they have pursued in office have been strikingly oriented toward deregulation, cuts in social programs that benefit the less affluent, and tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy. This distinguishes the peculiar American right-wing hybrid from most of its European counterparts.

Crucially, plutocratic populism also magnifies the party’s incentives to engage in anti-system behavior. Despite escalating extremism, billionaire-financed organizations have lavishly funded and backed U.S. right-wing populism. This direct source of radicalization, in turn, fosters an indirect one: The plutocratic policies that these investments encourage have so little support among Republican voters that party elites must further stoke populist backlash to animate the base.

The distinctive brand of U.S. right-wing populism has gone through two phases separated by President Donald Trump’s loss in the 2020 presidential election. Plutocratic populism 1.0 was more plutocratic than populist. Mobilizing against President Barack Obama after the 2008 election, the plutocratic elements of the party—the Federalist Society, the Koch brothers and their Americans for Prosperity advocacy group; the state-level “troika” of the AFP, American Legislative Exchange Council, and State Policy Network; and an increasingly partisan U.S. Chamber of Commerce—were in the driver’s seat when it came to Republican policymaking and power-building, and Democrats struggled to respond.

These organized forces attacked public-sector unions. They stacked courts with business-friendly judges. They went into overdrive with gerrymandering. And tax cuts and deregulation reigned supreme. The plutocrats paved the way for the rise of President Trump, whom most of these groups initially opposed. In 2016, President Trump ran against both the political left and the plutocratic right. In office, though, he outsourced policy to then-U.S. House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI) and staffed his White House with Americans for Prosperity alumni. His big legislative achievement were the 2017 tax cuts, which skewed toward corporations and the superrich. And he pushed through three U.S. Supreme Court appointments that yielded the most business-friendly majority since the court sought to thwart President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal.

In 2025, however, plutocratic populism 1.0 gave way to plutocratic populism 2.0. The Trumpist shift of the Republican Party, which accelerated after the insurrection at the Capitol in Washington on January 6, 2021, is driven by right-wing media, the party’s intense voting base, and a distinct subsection of the organizational right that sees cultural and racial backlash as the party’s superpower. President Trump has had years to identify loyalists, and these loyalists are seeking not just to dismantle disfavored parts of the administrative state but also to weaponize the whole system.

Some plutocrats, among them tech entrepreneurs Elon Musk (the richest person in the world) and David Sacks and their tech colleague and co-investor Peter Thiel, are strongly aligned with the Trumpist-dominated Republican Party. Far more of the plutocratic alignment with the Trump administration, however, stems from a combination of self-interested policy aims (deregulation and tax cuts) and acute fears of retribution by President Trump and his administration. Organized plutocrats once sought to dominate the party’s center of power; now, the party’s center of power seeks to dominate them. In this pay-to-play world, control has shifted toward the MAGA side of the Republican Party and to President Trump himself, with dangerous implications not just for Democrats but also for democracy.

If economic populism means policies to benefit those left behind, plutocratic populism 2.0 is no more economically populist than version 1.0. Indeed, in this respect, it is even less populist. Tariffs that disproportionately hurt those on modest incomes, cuts to spending on social programs, tax cuts for the wealthy, extensive deregulation, and an emerging system of favors and corruption for the well-positioned add up to a massively inegalitarian package of policies.

Yet this package is now coupled with an even more extreme set of anti-system strategies—including attacks on public-sector unions, elite educational institutions, and the expert-informed institutions that once guided public investments in health, science, and technology. Designed to quell dissent and mobilize supporters, these actions make it much harder for critics to break through, undermine normal mechanisms of electoral accountability, and create institutional opportunities for unpopular policy changes that few could have contemplated during President Trump’s first term in office.

Assessing President Biden’s record

This troubling transformation raises a fundamental question: Could plutocratic populism 2.0 have been stopped? A key goal of the Biden administration was to lessen growing place-based divisions and soften the appeal of right-wing populism. Why this strategy failed to produce quick or large electoral effects in 2024—and what this means for political and policy strategy now—is our final topic.

The first step in charting a path toward winning nonmetro working-class voters away from right-wing populism is a sober assessment of the Biden administration’s strategy for remaking policy to strengthen appeals to these voters. It is now common to say that the strategy of improving job opportunities, well-being, and opportunities for unionization—sometimes known as “deliverism”—failed.10 The evidence, however, points to a more complex evaluation.

Electoral performance in the global context

The starting point for that evaluation is the recognition that in 2024, the incumbent Democratic administration faced a historically challenging global political environment. In Europe, governments of the left (Germany) and center (France) lost considerable ground. But so did parties of the right, with the British Conservatives posting their worst showing in their much longer history. Similarly, in Asia, the long-dominant center-right Liberal Democratic Party in Japan suffered its second-worst results ever. Post-COVID disaffection and, more specifically, a bout of pandemic-induced global inflation provoked electoral punishment for incumbent parties almost everywhere.11

Gauged against that backdrop, the Democrats’ electoral performance in 2024 actually looks relatively good. Although Vice President Kamala Harris lost ground almost everywhere, compared with Joe Biden in 2020, she came close to victory in the presidential contest. She lost the popular vote by just 1.5 percentage points—one of the closest results in recent U.S. history. And while some might note, rightly, that President Trump himself was a weak candidate, Democrats actually gained a couple of seats in the U.S. House and narrowly lost the U.S. Senate, despite an unfavorable map (victims of the density divide). Breaking recent patterns, four Democrats—in Arizona, Michigan, Nevada, and Wisconsin—won or held Senate seats in states that President Trump carried.

Democrats—and their presidential standard-bearer in particular—clearly paid an electoral price for high inflation. The damage likely would have been much worse, however, if the United States had not managed, in considerable part through vigorous (and, until 2021, bipartisan) stimulus, to generate an economic recovery in growth, productivity, and employment that far outpaced those of other rich democracies.

An incomplete agenda and implementation

The 2024 election represented a particularly difficult test for the Biden administration’s theory of coalition expansion in another respect, too. The institutional gridlock the administration confronted blocked very significant parts of its “deliverism” ambitions. Its proposed Build Back Better legislation had to shrink drastically to pass through the evenly divided U.S. Senate. Moreover, the parts that passed were often the least visible, direct, and politically traceable, such as tax credits to businesses to create new good jobs, which workers likely credit to the private sector, not government. And conservative courts blocked important administrative initiatives on student loan forgiveness and other issues.

Perhaps most deserving of emphasis is the manner in which halting implementation of the Biden administration’s infrastructure investments exacerbated these challenges. Many highly touted and costly investments struggled to break ground. By early 2025, only four states had worked through the administrative process for expanding rural broadband access. Only a handful of the promised charging stations intended to increase the attractiveness of electric vehicles had actually been installed. Even something seemingly straightforward—the $35 cap on insulin prices for Medicare patients—did not go into effect until 2025. The same was true for the highly popular initiatives to negotiate Medicare prices on important drugs.

Thus, the electoral trial of 2024 was a test of an incomplete version of the Biden agenda, sluggishly implemented, and facing the voters under quite unfavorable circumstances that were largely outside the administration’s control. These are among the reasons why a positive feedback loop between policy initiatives, voter attitudes, and election results largely failed to emerge.

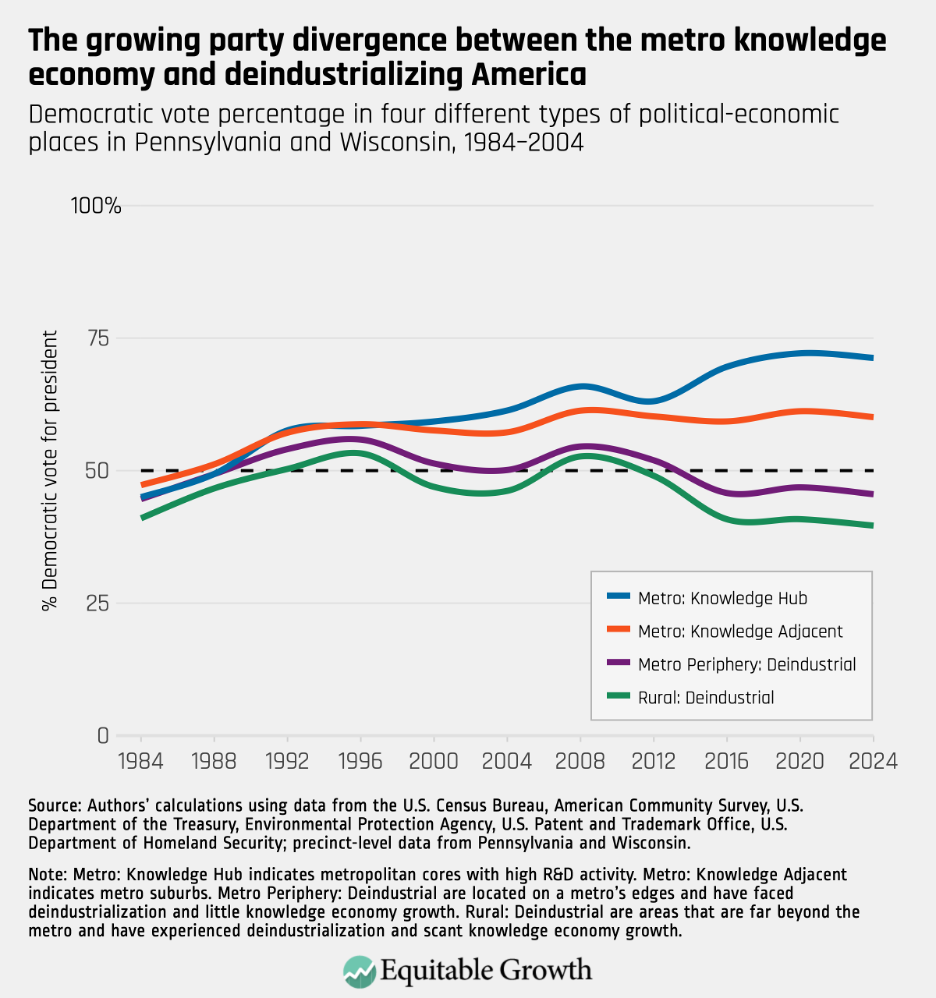

We can see the limits of feedback in the 2024 election results. Figure 2 below focuses on two electoral battleground states—Pennsylvania and Wisconsin—with strong industrial histories and where the effects of the Biden administration investments might have been expected to show up in the election results. The figure shows four clusters of places in these two states, based on their changing mix of industrial and knowledge economy activity.12

Knowledge economy metro areas have shifted toward the Democratic Party, especially after 2010, while rural deindustrializing areas have shifted toward the Republican Party. On the periphery of metro America, suburban areas that are adjacent to metro knowledge hubs have moved toward Democrats, while those that have experienced deindustrialization without such knowledge economy ties have moved toward Republicans—in both cases less sharply than metro and rural areas, respectively.13 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

What is clear from Figure 2 is that these trends did not change appreciably in 2024 in either state. The geographic divisions that exploded between the Obama and (first) Trump presidencies appear quite locked in today. Certainly, the Biden administration did not achieve a much higher vote share in 2024 than in 2020 in the nonmetro places marked by deindustrialization.

Newfound limits of policy feedback

While no doubt disappointing to Biden administration officials, the limited feedback effects of its initiatives are consistent with recent scholarship on political behavior. This research mostly finds much weaker positive behavioral effects of policy initiatives than seen in prior research. The most extensive studies have focused on the Affordable Care Act, and they generally show that initial impacts in the mid-2010s were negative. Only after an extended period did public attitudes turn positive—tellingly, in the wake of Republican efforts to repeal the program early in the first Trump administration.14

At the heart of this discouraging record is disillusionment with government, especially among the White working class and in rural areas. Informational environments that mute or distort messages of new programs reinforce this distrust. The growth of partisanship as a political identity—combined with much more intense dislike of the party one does not identify with—has made it considerably more difficult to shake up voter attachments through policy action.15

In thinking about the difficult task of persuasion, it is worth emphasizing that disenchantment has been a long-term process, now reinforced by many social and cultural factors. It is unrealistic to think that policy change alone is going to produce a dramatic and rapid reversal. But there is reason to think that policy can help. More important, unlike many other things that will matter, policy is something over which decision-makers can exercise control.

Despite the grave risks facing our democracy, there is reason to believe that those seeking to contain right-wing populism may have an opportunity to exercise such control in the future. How they should approach this potential opportunity is our final topic.

Prospects for Democrats’ future progress

The cautious case for believing that results could be more favorable next time builds on three fundamental points. First, as has been common in recent U.S. history, considerable political momentum may emerge from backlash to the current administration and its policies. Second, while that administration and its policies have greatly undermined the public sector, backlash-driven campaigns for change are likely to emphasize the need to improve government capacities at the state and local levels, as well as the federal level. Finally, against this backdrop, lesson-drawing from the Biden record could increase the prospects that future initiatives targeting the economic well-being of working-class voters are visible, legible, effective, and popular.

Disillusionment with government and strengthening political attachment to the Republican Party among working-class voters undermined deliverism. Already, however, there are signs that the economic policies of the new Republican administration may be weakening those attachments, especially among the least committed Republican voters. Neither the Musk-led attacks on federal government agencies nor President Trump’s trade wars are popular. The prominence of an unpopular billionaire (Elon Musk) in the new administration undercuts the Trump administration’s populist bona fides.

Crucially, as noted, many of the administration’s policies are likely to be quite damaging to working-class and especially rural voters. This creates important opportunities to reach out to voters who have flocked to the banner of right-wing populism.

Disapproval of the president on the economy is already high and growing—a contrast with his first term in office, when the economy was often his most popular issue.16 And this is before the negative impact on employment and prices of these policies kick in. It is also prior to the possible passage of the Republican budget reconciliation package of high-income tax cuts combined with sizable cuts in Medicaid and food assistance, which is also likely to be quite unpopular.

Indeed, when asked in a recent poll whether voters favored cutting Medicaid to pay for tax cuts, 70 percent of voters were opposed, compared to 20 percent in favor, with swing voters opposed 67 percent to 21 percent, and even Trump voters opposed 51percent to 36 percent.17 Just as was true after 2004 and 2016, an unpopular Republican presidency may create considerable political opportunities.18

Lessons for future policymaking

The challenge in reaching those drawn to right-wing populism through economic policies is to put in place initiatives that generate material benefits and expanded opportunity and that are perceived to be doing so as close to implementation as possible. Democrats from 2021 to 2024 did moderately well on the first half of this equation, providing short-term stimulus and long-term investments that fueled job creation in many “left behind” areas. They fell short, however, on the second half.

As Equitable Growth’s Alexander Hertel-Fernandez and Shayna Strom discuss in their essay in this series,19 deliverism failed to incorporate many of the cautions and caveats coming from recent political science scholarship. These implications are not all negative—policy feedback can break through partisan polarization—but they point to critical necessary conditions. Three in particular stand out:

- Policies need to be visible and traceable. Decades-old scholarship about how voters assess policies still holds.20 If voters do not perceive that a policy has affected them and/or do not know to whom to give credit or blame for that policy, new initiatives are unlikely to generate the kind of positive feedback loop that policymakers are looking for.

- Policies should reinforce a sense of dignity and status tied to democratic citizenship, as well as provide benefits. Particularly in a political climate marked by disaffection, positive reactions to policies are in part a matter of symbolism. They involve not just material benefits but also moral recognition—a sense that recipients are seen and their efforts appreciated.

- Policies are more likely to succeed when they activate organized supporters. In challenging and often hostile information environments, voters need organized allies who have the resources and credibility to enhance visibility and traceability. Even where voters experience governance directly, they often rely on trusted sources to develop their interpretations of those policies.

Although it is outside our purview, we wish to acknowledge that the challenge of creating these favorable perceptions is in considerable part one of communications. Making new programs visible to voters—especially the most skeptical ones—in today’s information environment is extremely difficult. Policy news seldom reaches the disengaged, and many of the disaffected are in partisan informational spaces disinclined to provide favorable or accurate coverage.

Even less-partisan media sources have incentives to play up the negative or controversial in their reporting. Having effective, empathetic organized messengers can help. So can new efforts to penetrate informational spaces popular with the politically disengaged.

Improving state capacity

For those focusing on the tools of governance, the priority is policy initiatives that lend themselves to clear and straightforward narratives of benefit for U.S. families. Enacting and funding initiatives is not enough. These initiatives also must rapidly translate into actual changes in lived experience that can be persuasively attributed to government action.

Without wading too far into the debate about so-called abundance framings, the case that procedural obstacles are far too often a roadblock to expeditious and effective policy change is extremely strong.21 The costs of building all kinds of infrastructure, as well as housing in many states, is now far higher in the United States than in comparable countries. And turning programs into facts on the ground takes far longer than it once did.

More broadly, various limitations of government capacity have become a major obstacle to turning ambitious policy plans into reality. In too many cases, intended beneficiaries confront a bewildering, sometimes overwhelming, set of roadblocks. Deliverism cannot work if the end results are not, in fact, delivered.

One reason for political optimism about future policy opportunities is that momentum is building to both reduce obstacles to implementation and bolster capacity for robust government action. Recognition of these roadblocks has grown among policy analysts and decision-makers. Generational turnover among policymakers, advocates, and thought leaders has encouraged a critical reevaluation of the benefits and costs of procedural barriers. A future set of initiatives targeted at working-class voters must be packaged with reforms to ensure that laws are not only passed but also implemented, and implemented quickly.

Elements of a new agenda

Ideas for place-based reforms and policies to boost working-class economic security and power abound—including a number that were part of the original Build Back Better legislation but did not make it into the Inflation Reduction Act. We close, therefore, not by laying out a laundry list of possible policies but by emphasizing what we think the key themes of these efforts should be. We focus on initiatives designed to address geographic polarization, the decline of working-class support for the center left, and the widespread mistrust of government and sense of economic dislocation that contribute to this decline.

The first theme is tackling the concentration of market power. The nation’s affordability crisis rests in considerable part on growing consolidation in sectors as diverse as telecommunications, meat processing, and pharmacies. The concentration of market power has led to both economic and political challenges. It is highly implicated in the decline of rural America. As the sociologist Robert Manduca has shown, “The waves of corporate consolidation over the past four decades have deprived many cities and towns of the corporate headquarters and local businesses that used to be a source of high paying jobs and demand for professional business …. [and] a strong predictor of community and civic health.”22

Market power often leads directly to political power. Rent-seeking interests have become an important part of the plutocratic populist coalition. Cases in point include big oil companies, the cryptocurrency industry, and many sectors of the tech economy. Addressing market concentration thus can both lead to direct material improvements for aggrieved voters and help to rebalance political power.

Equally important are efforts to reduce prices and boost supply in key sectors through the removal of process-related obstacles. In some crucial regulated markets—especially housing, but also education, electricity, and health care—regulatory reforms could lead to lower prices. This kind of regulatory reform is popular, effective, frees up public funds for other purposes, and generates higher productivity in the service sectors that now account for the bulk of employment.

The case for addressing these market power and price challenges is strengthened by recent evidence suggesting that there may be greater popular support for “predistributive” programs, such as antitrust actions and support for labor unions, than for redistributive ones, such as trade adjustment assistance and anti-poverty spending.23 At a time when suspicion of redistributive programs has grown among working-class voters, programs that boost market incomes and make key consumption goods less costly may be more attractive options.

Conclusion

Policy reforms along these lines—pursuing, for example, visible measures to reduce costs for health care and education while spurring expanded and more affordable construction of housing and infrastructure to meet demand, increase productivity, and create jobs—would have two important impacts on the spatial inequalities that have helped generate support for right-wing populism. First, by helping to address the affordability crisis in high-productivity areas, such policies would increase mobility to the places with greatest economic opportunity while slowing the population drain of the non-college-educated from those areas.

Second, out-migration of labor from disadvantaged areas should increase demand for workers among those who remain in areas left behind.24 Other authors in this series of essays show that non-college-educated workers in these areas tend to stay put and experience low economic mobility or drop out of the job market altogether when economic shocks occur. Predistributive policies could help address these ills and slow the population drain from those areas.

Even with such policies, it will remain important to target resources directly to disadvantaged communities to address both social dislocation and political disaffection. Realism will be needed in these efforts. Voters in distressed communities are deeply skeptical that government initiatives can make their lives better. That skepticism has developed over decades, is reinforced by the decline of local businesses and labor unions, and will not fade overnight, especially given the political homogeneity of many of these communities and the influence of nationalized media. Change will take time.

Still, in our nation’s closely balanced politics, where the plutocratic populist Republican Party has struggled to produce even razor-thin majorities, modest improvements could have decisive political effects. Reducing the sway of right-wing populism will require that Democrats and their allies focus on emerging political opportunities and the careful design of interventions that can seize those opportunities as they develop. Density is not destiny, and lessening the nation’s geographic divide is critical to rebalancing and strengthening U.S. democracy.

About the authors

Jacob Hacker is the Stanley B. Resor Professor of Political Science at Yale University. He is the co-director of the Ludwig Program in Public Sector Leadership at Yale Law School, director of the American Political Economy eXchange at the Institution for Social and Policy Studies, and co-director of the multi-university Consortium on American Political Economy.

Paul Pierson is the John Gross Distinguished Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley. He is the director of the Berkeley Economy and Society Initiative and co-director of the multi-university Consortium on American Political Economy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Alex Hertel-Fernandez for extremely helpful comments and the entire Equitable Growth production team for excellent and expeditious editorial and production work. Very special thanks to Lucas Kruezer, a predoctoral fellow at Yale’s American Political Economy eXchange, for the brilliant data work behind the two figures.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!

End Notes

1. David Autor and others, “Places versus People: The Ins and Outs of Labor Market Adjustments to Globalization.” Working Paper 33424 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2025), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w33424.

2. Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson, Let Them Eat Tweets: How the Right Rules in an Age of Extreme Inequality (New York: Liveright, 2021), available at https://wwnorton.com/books/9781631496844.

3. Jacob Hacker and others, “Bridging the Blue Divide: The Democrats’ New Metro Coalition and the Unexpected Prominence of Redistribution” (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2023), available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/perspectives-on-politics/article/bridging-the-blue-divide-the-democrats-new-metro-coalition-and-the-unexpected-prominence-of-redistribution/3FD0D61D57DB06630D9046DC9348159D.

4. Joseph Parilla and Glencora Haskins, “The Bidenomics investment boom in red America” (Washington: The Brookings Institution, 2024), available at https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-bidenomics-investment-boom-in-red-america/. Strategic sectors are clean energy, semiconductors/electronics, biomanufacturing, and other advanced industries; red counties are those that voted for President Trump in November 2024.

5. The MIT Elections Lab provided 2004–2022 election data. The U.S. House of Representatives Office of the Clerk provided 2024 election data. American Community Survey 5-year estimates (2006–2023) through tidycensus provided population and median household income data. Congressional district results were matched with the American Community Survey closest in time (ACS 2005–2009 matched with the 2004, 2006, 2008 elections; ACS 2006–2010 matched with the 2010 election; and ACS 2019–2023 matched with the 2024 election). St. Louis FRED provided Consumer Price Index data to deflate household income. Congressional districts were coded as Democratic or Republican by the winning candidate’s party and by election year. Median population density and household income amounts were calculated for all districts by party and by election year.

6. David A. Hopkins, Red Fighting Blue: How Geography and Electoral Rules Polarize American Politics (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

7. Eliott Ash and others, “From viewers to voters: Tracing Fox News’ impact on American democracy,” Journal of Public Economics 240 (2024), available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047272724001920; David E. Broockman and Joshua L. Kalla, “Consuming Cross-Cutting Media Causes Learning and Moderates Attitudes: A Field Experiment with Fox New Viewers,” The Journal of Politics 87 (1) (2025): 246–261, available at https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/730725; Chris Fleisher, “The partisan news effect on politics,” American Economic Review, November 1, 2027, available at https://www.aeaweb.org/research/fox-news-cable-bias-impact-on-swaying-voters-right; Kayla Gogarty, “The right dominates the online media ecosystem, seeping into sports, comedy, and other supposedly nonpolitical spaces,” Media Matters for America, March 14, 2025, available at https://www.mediamatters.org/google/right-dominates-online-media-ecosystem-seeping-sports-comedy-and-other-supposedly.

8. Michael E. Shepherd, Derek App, and Christian Cox, “Access to Healthcare and Voting: The Case of Hospital Closures in Rural America,” American Political Science Review (2024), available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/385259639_Access_to_Healthcare_and_Voting_The_Case_of_Hospital_Closures_in_Rural_America.

9. Hacker and Pierson, Let Them Eat Tweets: How the Right Rules in an Age of Extreme Inequality.

10. Deepak Bhargava, Shahrzad Shams, and Harry Hanbury, “The Death of Deliverism: Why Policy Alone Is Not Enough,” New Labor Forum 33 (1) (2023), available at https://doi.org/10.1177/10957960231221761.

11. Richard Wike, Moira Fagan, and Laura Clancy, “Global Elections in 2024: What We Learned in a Year of Political Disruption” (Washinton: Pew Research Center, 2024), available at https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2024/12/11/global-elections-in-2024-what-we-learned-in-a-year-of-political-disruption/.

12. Identifying the four economic development clusters involved a two-step process. First, industrial and knowledge economy activity was measured at the census-block group level from 1976 to 2024 using a variety of geolocated data. Industrial activity was captured using manufacturing and mining employment data from the U.S. Census Bureau and American Community Survey, as well as proximity to railroads using U.S. Department of Transportation data and to factories using Environmental Protection Agency data. Knowledge activity was measured using research and development sector employment (professional, scientific, management, education, and health care services) and bachelor’s degree attainment (using Census data and the American Community Survey), as well as proximity to patent activity (using data from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office), universities, and hospitals (using data from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security). Second, a k-means cluster analysis was performed using these measures to sort block groups into the four groups in the figure—Metro: Knowledge Hub, Metro: Knowledge Adjacent, Metro Periphery: Deindustrial, and Rural: Deindustrial—that roughly follow a center-periphery model.

13. Precinct data were collected, cleaned, and standardized for Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. Harvard University’s Record of American Democracy provided 1984 and 1988 data; Pennsylvania’s Department of State and the University of Wisconsin-Madison Geography Department provided 1992 to 2024 data. Precinct data were matched with voting district shapefiles closest in time and then standardized to 2020 block group boundaries using a masked asymmetric areal interpolation using a national land cover raster from the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Land Cover Database. Standardization provides stable boundaries across time that can be paired with Census and American Community Survey data. This process yields approximately 10,170 block groups for Pennsylvania and 4,000 for Wisconsin.

14. Suzanne Mettler, Lawrence R. Jacobs, and Ling Zhe, “Policy Threat, Partisanship, and the Case of the Affordable Care Act,” American Political Science Review 117 (1) (2022), available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-political-science-review/article/policy-threat-partisanship-and-the-case-of-the-affordable-care-act/89838A7E75F39A339D540058EE1D55CB; Daniel J. Hopkins, Stable Condition: Elites’ Limited Influence on Health Care Attitudes (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2023), available at https://www.russellsage.org/publications/stable-condition.

15. Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson, “Policy Feedback in an Age of Polarization,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 685 (1) (2019), available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0002716219871222.

16. Domenico Montanaro, “More give Trump an F than any other grade for first 100 days, poll finds,” NPR, April 29, 2025, available at https://www.npr.org/2025/04/29/nx-s1-5379596/trump-100-days-polling-grade-approval-rating.

17. Tony Fabrizio, Bob Ward, and John Ward, “Memorandum: Medicaid Attitudes Poll,” Memorandum, FabrizioWard+, April 2, 2025, available at https://modernmedicaid.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/MMA-Poll-Memo-4-2-25.pdf.

18. We acknowledge the very real questions about whether the 2026 and 2028 elections will unfold in an environment that allows public disapproval to meaningfully alter the balance of political authority. But for the purposes of this analysis, we assume that dynamics of reasonably open political competition will still apply.

19. Alexander Hertel-Fernandez and Shayna Strom, “Designing economic policy that strengthens U.S. democracy and incorporates people’s lived experiences” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2025), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/designing-economic-policy-that-strengthens-u-s-democracy-and-incorporates-peoples-lived-experiences/.

20. R. Douglas Arnold, The Logic of Congressional Action (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990).

21. Jennifer Pahlka and Andrew Greenway, “The How We Need Now: A Capacity Agenda for 2025 and Beyond” (Washington: The Niskanen Center, 2024), available at https://www.niskanencenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Niskanen-State-Capacity-Paper_-Jen-Pahlka-and-Andrew-Greenway-2.pdf.

22. Robert Manduca, “Antitrust Enforcement as Federal Policy to Reduce Regional Economic Disparities,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 685 (1) (2019), available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0002716219868141.

23. Jacob S. Hacker, “The institutional foundations of middle-class democracy,” Policy Network 6 (5) (2011): 33–37, available at https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&user=-fjTjLQAAAAJ&citation_for_view=-fjTjLQAAAAJ:Y0pCki6q_DkC; Ilyana Kuziemko, Nicolas Longuet-Marx, and Suresh Naidu, “‘Compensate the Losers?’ Economic Policy and Partisan Realignment in the US.” Working Paper 31794 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2023), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w31794.

24. [1] Tim Bartik, “Federal and state governments can help solve the employment problems of people in distressed places to spur equitable growth” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2025); David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson, “How the China trade shock impacted U.S. manufacturing workers and labor markets, and the consequences for U.S. politics” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2025).