Executive actions to reform the cost-benefit analysis of U.S. tax regulations

Overview

Beginning in April 2018, the federal government required a cost-benefit analysis for many more tax regulations than it had in the past. More than 2 years later, it is clear this experiment in cost-benefit analysis of tax regulations failed. The cost-benefit analyses released alongside regulations implementing the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 provide little information relevant to assessing the merits of those regulations. Moreover, while tax experts criticize many of the TCJA regulations for providing unmerited windfalls to favored groups, the cost-benefit analyses for those regulations often fail to identify these windfalls or provide critical analysis of them.

The weaknesses of these analyses are rooted in the framework that the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs mandates for the cost-benefit analysis of federal regulations by executive branch agencies. This framework is fundamentally ill-suited to the evaluation of tax regulations.

First and foremost, this framework treats revenue increases as neither a cost nor a benefit because a revenue gain for the government is accompanied by higher tax payments for some set of people. Yet because raising revenues is the primary purpose of taxation, this assumption means the resulting analysis cannot provide useful guidance in developing tax regulations. The framework assumes there is no reason for the tax system to exist.

The practical upshot of this approach to cost-benefit analysis is to bias the system in favor of tax cuts. A lax regulation that simply gives up on preventing some form of corporate tax avoidance, for example, could easily generate positive net benefits in this framework. This is because giving up on tax enforcement allows corporations to stop engaging in costly schemes to avoid paying taxes—they get a tax cut directly instead—and that is considered a benefit.

Yet the revenue loss itself would not be treated as a cost. In the same way, a more stringent regulatory interpretation that shuts down corporate tax avoidance could have positive costs—the firms might spend more money on lawyers and accountants to avoid paying tax—and no benefits. The higher revenues themselves would not be counted as a benefit.

In addition, the framework that the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs mandates agencies use for cost-benefit analysis relegates changes in the distribution of the tax burden to second-tier status. Though it may seem neutral to instruct the U.S. Department of the Treasury and the IRS to ignore changes in the distribution of the tax burden, it is not. High-wealth taxpayers are generally better able to avoid tax than low-wealth taxpayers. This framework thus puts a thumb on the scale for shifting taxes from the wealthy to everybody else.

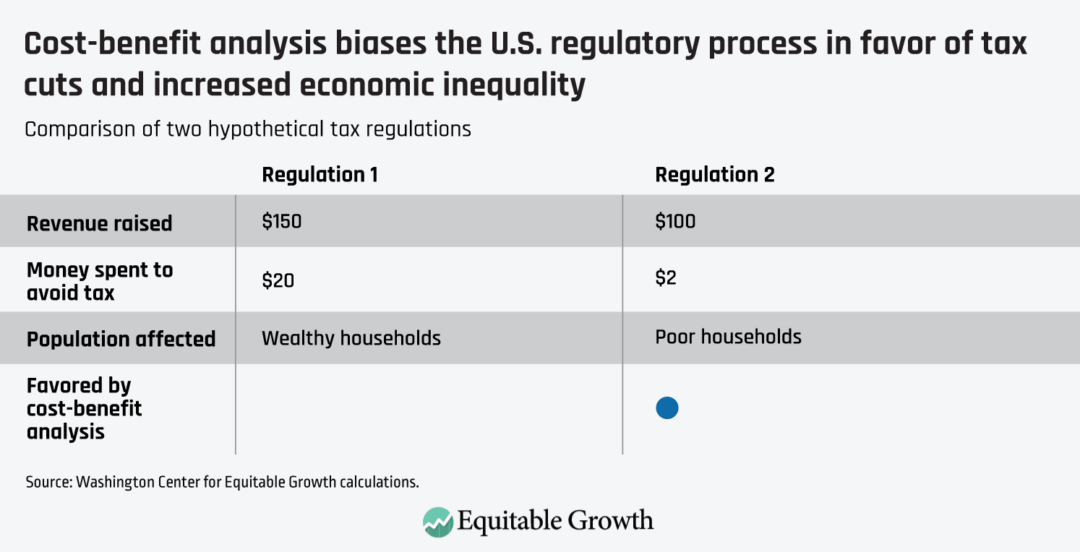

For example, suppose the Treasury Department and the IRS are considering two regulations. The first would raise $150 from rich taxpayers, who would also spend $20 on accountants and lawyers to work around the regulation. The second would raise $100 from poor taxpayers who would only spend $2 to try and avoid the tax. The cost-benefit framework would tell the Treasury Department and the IRS that the second regulation would be the better approach as it would result in only $2 spent on tax avoidance. The higher revenue and more progressive distribution of the first regulation that would require wealthier taxpayers to pay more tax would receive no weight.

Moreover, if the agencies had previously issued the first, more progressive regulation, this framework would say that withdrawing that regulation and replacing it with the regulation raising less money from poorer people would yield $18 in net benefits and thus be a great project to pursue. (See Table 1.)

The framework for cost-benefit analysis that the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs instructs agencies to use is often described as disregarding redistributive impacts. But, as the preceding example makes clear, it would be more accurate to say that it adopts a specific and regressive view on how to judge redistributive impacts.

Evaluating the merits of a tax regulation requires assessing the impacts of that regulation on tax revenues and the tax burden. These are the most important considerations in any tax change. Do the revenue losses prevented by a more stringent interpretation of the law justify the burden imposed, taking into account who would bear that burden? Or does the burden reduction resulting from a lax interpretation, taking into account who would benefit, justify the revenue loss? The cost-benefit analysis that the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs currently instructs agencies to produce cannot answer these questions.

Executive action

The Biden administration should eliminate the requirement for cost-benefit analysis of tax regulations, as well as the authority of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs to review that analysis. Instead, the Treasury Department should provide a qualitative and, when feasible, quantitative evaluation of tax regulations. This evaluation should examine the impacts on:

- Revenues

- The level and distribution of the tax burden

- Compliance costs

The traditional types of analysis developed for the legislative context are exactly the types of analysis required to evaluate tax regulations. These analyses are the analog of the cost-benefit framework, taking into account the distinct purpose of tax regulations. Though cost-benefit analysis can be a useful framework for judging the economic impacts of certain regulatory changes, it is inappropriate and unhelpful to try to apply it to tax regulations.

Finally, the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s analysis of the impacts on revenues, burden, and compliance costs should focus on the decision points where the agencies have discretion to regulate differently, as this is the analysis that can inform regulatory decision-making. In addition, the analysis should be conducted only when different interpretations of the law would have substantially different effects. If the Treasury Department and the IRS lack discretion or all permissible interpretations have essentially the same effects, there is little value in requiring additional analysis.