Designing economic policy that strengthens U.S. democracy and incorporates people’s lived experiences

Overview

Around the globe, people are increasingly dissatisfied with the state of democratic capitalism. In the United States and other rich democracies, economic policy has too often in recent decades produced rising economic inequality across individuals, as well as regions within countries, stagnant economic growth and innovation, rising costs of essential goods and services such as housing, health care, and education, greater economic insecurity, and declining job quality and stability.

Voters have communicated their discontent with a surge of support for populist parties, politicians, and political causes that challenge incumbent elites and profess to speak directly to the needs of “real” people. In some countries, the populist insurgency has a left-wing character, but in most cases to date, voters have gravitated to populism’s right-wing variants such as the AfD in Germany, the National Rally in France, Fidesz in Hungary, the Sweden Democrats, and the UK Independence Party.

This essay is the first in a series Equitable Growth will publish by a number of experts exploring the implications of right-wing populism for those making and following U.S. economic policies. In this essay—and throughout the broader essay series—we stress three intellectual contributions of the overall series.

First, we argue that the surge in support for right-wing populism merits attention not just from political pundits and strategists, but also from policy leaders who research, design, and implement economic policies. Put simply, the downstream effects of economic policy for politics and democracy merit far more attention than they have been getting in policy design and implementation.

Second, we argue that meeting this new view of economic policymaking will require drawing from a broader set of scholarship than traditionally has been engaged in the U.S. economic policy process. That includes economics but also expands to cover work in political science and sociology.

And third, we argue that U.S. policymakers, who often are used to thinking about American exceptionalism, need to learn from the broader global shifts in support for right-wing populism around the globe. This means placing the U.S. experience with right-wing populism into the broader context of the global shift toward this movement, and to look for potential causes and levers to dampen support both abroad and at home.

The essay series thus lays out the case for why U.S. policymakers should approach economic policy with an eye to its downstream political effects on democracy, as well as descriptions of what this approach could look like across different policy domains.1 The essays take different approaches. Some focus on diagnosing how economic policy has produced conditions that fostered support for right-wing populism. Others propose new economic policy levers for mitigating the appeal of right-wing populism.

No series could cover all of the possible connections between economic policy and right-wing populism. Instead, our goal is to offer a model of an approach to the design of economic policies that takes seriously how people experience the economy and society’s need for democracy. The essay series will cover a variety of important policy areas and invite further scholarly engagement. Importantly, we seek to model the kind of approach we think is necessary from research and policymaking, one that incorporates more disciplinary perspectives (especially from political science and sociology) and one that considers the United States in a comparative context, learning from the experiences of other countries around the world.

It is important to note that the turn toward right-wing populism in the United States not only threatens democratic institutions and systems but also puts Americans’ economic well-being at risk. Economic policy can work to counteract this trend and bolster U.S. democracy—but is less likely to do so as it has traditionally been developed. At a time when the broader policy community is still debating the implications of the 2024 presidential election results and the extent to which it was a referendum on former President Joe Biden’s economic policies, we hope that this essay series will broaden the debate about the future of economic policy and politics in the United States at a moment of democratic crisis.

Defining right-wing populism and reviewing its recent surge in support

There are numerous dueling definitions of right-wing populism.2 We adopt the definition offered by comparative political scientist Sheri Berman at Barnard College. This definition captures the core features of most right-wing populist movements: appeals and positions that emphasize “a Manichean, us-versus-them worldview in which the ‘us refers to the ‘people,’ defined often in ethnic or communal terms and seen as engaged in a zero-sum battle with ‘them,’ defined most often as liberal elites, the establishment, and minorities and/or immigrants’.”3 Equally important to the “us-versus-them” nature of right-wing populism, according to Berman, is its “disdain for many of the basic norms and institutions of liberal democracy, such as free speech, freedom of the press, recognition of the legitimacy of opposition, and acceptance of the separation of powers in general and limits on the executive in particular.”4

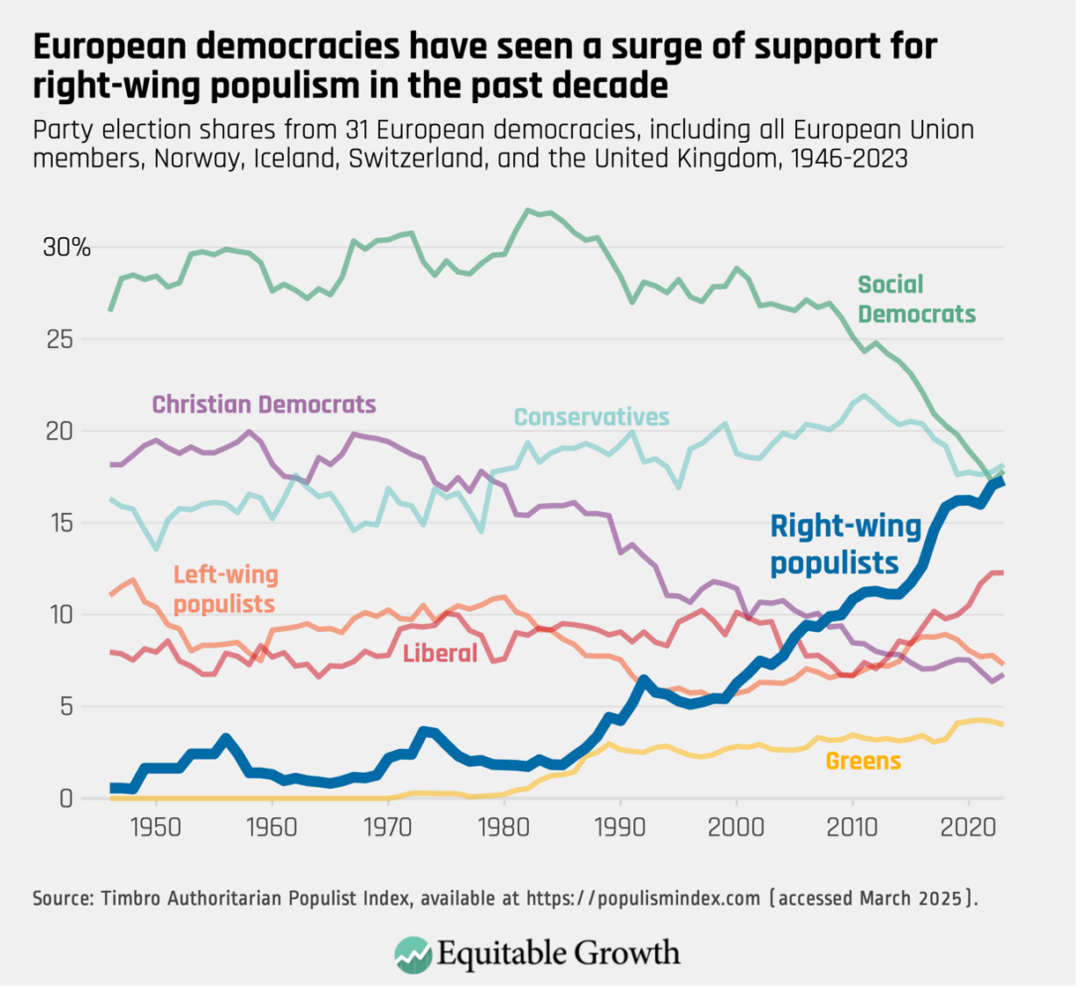

Data from the Timbro Authoritarian Populist Index,5 which tracks the electoral support that left-wing and right-wing populist parties have received in 31 European countries, show changing dynamics between European political parties between 1945 and 2023. More specifically, we can see that left-wing populism has fallen from its immediate post-World War II peak, while right-wing populist candidates and parties have steadily grown their mass electoral support. Support for right-wing populist politicians has now surpassed other traditional center-right parties (notably the Christian Democrats) and now is on par with stalwarts of the left (notably Social Democratic and Labor parties) and traditional conservative parties. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The United States is no exception to this trend. The Great Recession of 2007–2009 and its aftermath saw the rise of the Tea Party,6 a right-wing populist movement that fused a variety of sometimes-contradictory views.7 These included opposition to financial bailouts for homeowners and financial leaders perceived to be undeserving, nativist appeals against immigrants, support for protection of traditional social benefit programs for deserving citizens (especially Social Security and Medicare), and skepticism of new government initiatives to control climate change and expand health care to those perceived to be undeserving such as young people and communities of color.

The Tea Party, in turn, laid the foundation for the surprise 2016 Republican Party nomination, 2016 election, and eventual reelection of Donald J. Trump to the presidency in 2024.8 Departing from decades of Republican orthodoxy,9 Trump’s presidential campaigns—though generally not his first-term governing agenda—pivoted to a right-wing populist platform, stressing protectionism, protection of core social programs for deserving Americans, and ethnonational attacks on immigrants.

Much ink has been spilled between pundits, scholars, and political strategists over the sources of President Trump’s rise and reelection in 2024.10 But far too often, such takes have been based on the U.S. experience alone, pointing to idiosyncratic aspects or choices of the candidates in question and failing to recognize how right-wing populist shifts in the United States are part of broader global trends—trends linked to changes in economic policies over the past five decades.

Democracy and experience of the economy as goals for economic policy design

Why should policymakers—especially those focused on economic policy—care about the surge in right-wing populism in the United States and around the globe? Traditionally, economic policymakers have not tended to think about the downstream political implications of their policies, focusing instead on putting forward policies that maximize preferred economic outcomes.11

While this essay series is not primarily aimed at critiquing economic policymakers, it also exists in the context of a broader debate that economic policymakers and economists have been having about the appropriate way to make economic policy. Recently, economists have struggled with their own sense of relevance in a Biden and Trump world.12 This essay series suggests that focusing policy purely on economic outcomes, as many economists have traditionally done, and the very real economic trade-offs policymakers must grapple with,13 is crucial but not sufficient at this moment in history.

The rise in right-wing populism across the globe requires economic policymakers, including in the United States, to think about how their proposals shape not just economicoutcomes in a narrow sense but also people’s experiences of the economy, filtered through their social identities, narratives, and social institutions and organizations.14 To put a finer point on it, thinking about economic outcomes also requires thinking about democracy. Doing so is essential because of the threat that right-wing populism poses to both the U.S. economy and democracy.

The track record of right-wing populists in power is clear. Across countries, these leaders and parties tend to pursue policies that erode the rule of law, attack the foundations of an independent civil society, including universities15 and the civil service,16 and entrench personalistic control over the levers of government. This is how right-wing populists assume unchecked control over government processes and decisions previously guided by the rule of law and independent expertise.17 Together, these interventions dampen economic growth and innovation and undermine the pillars of inclusive prosperity.18 Thus, even for policy leaders who typically only focus on economic outcomes, considering the downstream political consequences of economic policy matters because of the substantial negative economic threats of right-wing populism.

How economic policy can help explain support for right-wing populism

As the essays in this series will argue, economic policy plays an important role both in helping to explain the rise of right-wing populism in the United States and other rich democracies and in providing a lever to dampen support for populist candidates, causes, and parties.

To say that economic policy matters for the appeal of right-wing populism, however, is not to say that support for right-wing populism depends on a simple tally of the economic benefits and costs that individuals have experienced. Indeed, the large literature in economics, sociology, and political science on the origins of right-wing populism suggests that objective economic circumstances are only a modest predictor, at best, of right-wing populist support.19 Nor is it to say that economic policy is the only driver of support for right-wing populism, which includes many other factors we do not cover in this paper and may not be amenable to change through policymaking.

Instead, what we argue is that support for right-wing populism involves a more nuanced interaction between economic and cultural factors—interactions to which economic policymakers and researchers should be much more attuned than they have been as they think about policy design. Just as important to note, some hypothesized sources of support for right-wing populism—such as some forms of economic insecurity—can explain small shifts that may be relevant in the context of a close election, while other hypothesized mechanisms offer greater explanatory power working on deeper mechanisms.20

Below, we detail some of the variety of the scholarship that documents links between past changes in economic policy and support for right-wing populism in ways that merge economic and cultural dimensions and consider a range of important outcomes related to right-wing populist support.

Economic dislocations and the unresponsiveness of government social programs

Even as individual-level objective economic security is not consistently related to support for right-wing populist causes and candidates, there is stronger evidence linking the perceived failure of social policies, especially in the face of economic dislocations and shocks, to shifts to right-wing populism. As one study documented, regions in the United Kingdom that were exposed to austerity-induced cutbacks in social programs were more dissatisfied with UK politics and more supportive of Brexit.21

In a similar vein, an analysis of elections from 1990 to 2017 across rich democracies found that populist parties did better when incumbent parties made cuts to social spending, especially unemployment benefits, and populist parties fared worse when countries spent more on such benefits—evidence that compensating individuals and communities facing economic shocks can blunt demand for right-wing populism.22 And a third study found that government austerity, especially cutbacks to income support programs, pulls economically vulnerable regions and individuals to the populist right.23

Trade is an especially important dislocation that may drive support for right-wing populism,24 particularly when individuals feel their livelihood has been threatened by competition with other countries and especially when politicians can activate latent resentments and concerns about threats to the status of affected workers.25 There is some evidence from the United States that greater government support for trade-affected communities can mitigate these polarizing effects of trade.26

Beyond trade, scholars have also found that transitions to cleaner energy sources to address climate change can spur right-wing populist backlash among the populations who are most negatively affected by the costs of the transition, such as increased energy costs.27

Community and regional decline

In a similar vein, feelings of grievance from living in a “left-behind” region, especially regions hollowed out by deindustrialization and trade, can generate resentments that fuel support for right-wing populism.28 In Sweden, for example, research documented how depopulating areas experience negative spirals, with declines in local services sparking further out-migration.29 As conditions worsen, voters in those regions feel ignored by mainstream political parties, and savvy right-wing populist politicians have found strong electoral success in playing up resentments against urban areas.

That work from Sweden resonates with research on the United States, which found that rural and exurban areas feel neglected by politicians and public policies—even when their objective economic circumstances are similar to those in other regions. Those resentments can then fuel appeals made by right-wing populist candidates and parties.30

Cost-of-living shocks and inter-group competition

Although much attention on the appeal of right-wing populists has focused on rural versus urban cleavages, geographic differences even within urban areas matter. New research suggests that concerns about shocks to individuals’ cost of living—especially housing—can spur greater support for right-wing populism, especially when individuals feel they are in direct competition with immigrants for scarce resources.

Studying German rental markets, scholars recently documented that increases in local rent prices drive support for the populist right in urban areas, particularly among low-income voters who lack the resources to fully absorb potential rent increases and where individuals fear dislocation and threats to their social status.31 Similarly, in Austria, researchers found that individuals’ support for right-wing populist candidates and parties increases when they are more exposed to potential competition with immigrants over limited housing stock, exacerbating a sense of competition over scarce and valuable resources.32 And looking across Scandinavian countries, research found that homeowners left behind in surges of housing prices became strongholds of right-wing populist parties.33

Macrofinance, economic crises, and inequitable bailouts for economic elites

Another relevant area fusing economic and social concerns involves financial crises, and in particular the Great Recession of 2007–2009. Although business cycles do not appear to be strongly predictive of shifts toward the populist right, the experience of enduring financial crises, especially when paired with fiscal austerity-based responses by an incumbent government, have formed the basis for right-wing populist mobilization.

In the United States, for example, it was the 2007 financial crisis—and specifically the housing crisis and the subsequently proposed bailout measures—that fueled the proximate rise of the Tea Party movement within the Republican Party.34 Looking across more countries, scholars have argued that the “financial crises of the past 30 years have been a catalyst of right-wing populist politics. Many of the now-prominent right-wing populist parties in Europe, such as the Lega Nord in Italy, the Alternative for Germany, the Norwegian Progress Party or the Finn’s Party are ‘children of financial crises,’ having made their breakthrough in national politics in the years following a financial crash.”35

Loss of status

Another relevant dimension involves status, dignity, and fairness. Everyone has different forms of status across the various domains of our lives, derived from our identities as students, workers, family members, friends, volunteers, congregants, or hobbyists.

As we previewed above, scholars have found that when individuals’ sense of their social standing in their community falls, especially in ways that feel unfair, they become more receptive to appeals made by right-wing populists,36 who provide alternative forms of status, identifying the sources of declining status in out-groups (such as immigrants) and elites (such as corrupt politicians or cultural leaders). It is important to note that the loss of status and dignity is not just a proxy for economic class; the same study, using the European Social Survey (covering 25 European countries), demonstrated that income level, educational achievement, and occupational class “explain only a limited amount of the variance in subjective social status.”37

For instance, one researcher found that, looking across 11 Western European countries, when households experience greater labor market risk—though not actual unemployment—those households turn toward the populist right, reflecting threats to households’ social standing.38 Another study found that loss of economic status above and beyond absolute changes in individuals’ incomes predicts support for the populist right.39

Researchers of right-wing populism have dubbed this mechanism “nostalgic deprivation,” capturing “the discrepancy between voters’ subjective understandings of their current status and their perceptions about past positionality.”40

Dignity at work

While declining social status has many causes,41 one important way that people evaluate their social standing is through the meaning they find from their jobs.42 Threats to job security and quality—such as deskilling, automation, or offshoring—appear in research to be closely related to perceptions of economic unfairness,43 which, in turn, is linked to support for populist right-wing candidates.

By comparison, policies or institutions that improve workers’ jobs and status in the workplace can mitigate the appeals of right-wing populism. Unionized workers have objectively better working conditions and also report higher levels of social standing, dampening support for the populist right.44 In some cases, unions may also create social identities for workers that can build greater solidarity with others—including immigrants and other minority outgroups—in ways that diminish the appeals of right-wing populists.45

Conversely, declines in unionization may help explain rising support for the populist right, even in countries with previously high levels of union membership. Research on Sweden, for example, suggests that sharp declines in unionization through the mid-1990s can help explain the increase in support for right-wing populist voting among working-class Swedish workers.46

A new approach to economic policymaking: Going beyond ‘deliverism’ to craft policy that resonates with people

While in office, former President Biden pursued a set of economic policies that broke from traditional approaches for economic governance, recognizing the ways that trade, antitrust, and consumer regulatory policies have, over decades, often eroded working- and middle-class jobs and advantaged concentrated economic interests over workers.47 President Biden and his team sought to leverage historic new infrastructure investments to create high-quality new jobs in stagnating communities across the country. Building on new scholarship in economics and law, this bundle of approaches pursued by the Biden-Harris administration came to be dubbed “Bidenomics.”

The thinking behind Bidenomics and the framework we have laid out in this essay are quite aligned. Specifically, they both highlight how past economic policy decisions around trade and regulation have hollowed out working-class communities across the country and both focus on strengthening unions as an economic and democratic imperative, on checking outsized corporate influence on the economy and politics to boost government responsiveness to working- and middle-class workers and their families, and on investing in good jobs in specific communities and places, not just transferring money to people.

But there are some important ways in which our framework either goes beyond the Bidenomics approach or departs from it. Perhaps most notably, much of the Biden-Harris administration assumed that good economic policy decisions would speak for themselves. When presidential administrations make policy, they inevitably have a heuristic they use to quickly check whether a given policy design meets their internal goals. The Biden-Harris administration’s shorthand was sometimes dubbed “deliverism”—a strategy to achieve political support by producing concrete material gains for the public—and policies were evaluated internally in part by whether they fit the goals of deliverism.48

In fact, as has been widely reported, deliverism underlaid a lot of the administration’s strategy around the enhanced Child Tax Credit in the American Rescue Plan. This policy delivered hundreds of dollars in monthly benefits to more than 60 million children for one year. The administration hoped that the public would appreciate the benefits of the short-term CTC expansion and then demand that Congress continue those benefits in the longer term.

Yet the expansion of the Child Tax Credit failed to build a popular constituency for the program. Recipients of the tax credit were no more supportive of the Biden administration’s policies than nonrecipients, and Congress ultimately did not permanently expand those benefits.49

Part of what this essay series suggests is that expecting good economic policy to translate to good economic outcomes, which, in turn, will translate to political support for democracy, is misguided. As we described above, a large literature in the social sciences suggests that we cannot expect changes in individuals’ material conditions, on their own, to produce changes in an individual’s political views and actions—let alone changing their attachment to democracy—especially on such a short-term basis.

For policies to register political impacts, policymakers must craft policies that can resonate in individuals’ lives, and especially with their identities and the narratives that structure their worldviews over time. As one of us recently argued in Democracy Journal,50 this will require significant changes to policy development, implementation, and messaging and narrative—and also will take time. People need to “see” themselves in the design and delivery of policies.51

New criteria for economic policymaking

More research and experimentation is needed to help flesh out what a comprehensive approach to policymaking would look like when it takes into account people’s experiences of the economy, their identities and narratives, and support for democracy. But drawing from the essays in this series, as well as our reading of the social science literature on right-wing populism and economic policy, we sketch out several criteria for policymakers to consider.

First, economic policies need to affirm and activate people’s identities, especially their agency, dignity, and social standing. Too much of the U.S.-centric work on the appeal of right-wing populism creates a false dichotomy between whether voters were racist or xenophobic or whether they were responding to material shifts in economic conditions.

As this essay proposes, a more productive perspective—and one that aligns with existing research from around the world—is that what matters for many voters is a sense of agency and dignity in their own lives. The task then for policymakers is to craft policies that affirm social standing, agency, and dignity, especially for individuals whose standing might feel threatened by changing economic, demographic, or social changes, thus tackling “nostalgic deprivation.”52

One especially important source of identity involves community and place, and as such economic policies need to recognize that community and place matter to voters—especially in the U.S. political context, with its territorially defined system of political representation.53 Past research on support for right-wing populism in the United States and abroad stresses how important perceptions of community decline are for generating resentment against government agencies, as well as demographic groups perceived to be undeserving, such as immigrants, young people, or others who are seen as benefiting from government interventions while one’s own community is neglected.

For many years, economic policy has stressed the importance of “people over places,” encouraging fiscal transfers to individuals experiencing economic hardship and supporting policies that could help move individuals from economically distressed regions to more productive areas. Yet such policies fly in the face of the dense social connections and practical realities that moor individuals to specific places and ignore the ways that communities’ perceptions of neglect fuel right-wing populist appeals. Policymakers need to focus on programs that can reinvest in communities experiencing economic and social decline and, in the process, provide alternative narratives about the standing of individuals living and working in those communities.

A potential starting point for policies that reinforce, activate, and support social identities and dignity is shifting the balance of economic policy. Our current system often focuses predominantly or exclusively on “compensating the losers”54 of trade, automation, globalization, and other economic shifts through government transfers after these individuals experience dislocations. We propose a modification, to an approach that more heavily weights predistribution—changing the balance of economic power, resources, and outcomes before tax-and-transfer policies by intervening directly in markets to reduce inequality.

One example of this approach is increasing the minimum wage rather than increasing tax credits available to those workers, thus shifting underlying economic and political resources and power.55 In tandem with this predistribution approach, policymakers might also prioritize efforts that rebuild good jobs in specific communities, attacking the root problem from multiple angles.

Last, people need to perceive that the government is meeting their needs and not simply acting on behalf of economic elites. Past research from the United States and abroad makes clear the toxic brew generated by a sense that the government is not acting on one’s behalf, especially during periods of economic risk or dislocation. The contribution of financial crises, in which the government is seen as bailing out financial institutions while neglecting the economic strains faced by working and middle-class Americans, is one example of this dynamic, as is the finding that more generous Unemployment Insurance buffered the effect of economic crises on support for right-wing populists across European democracies.

This will require economic policies that adequately meet the economic risks faced by citizens, of course. But policies also must go beyond simple risk-buffering to actively show citizens the role that the government is playing in their lives. This means that policies must be visible, tangible, and traceable back to the government.56

In the United States, this has always been a daunting task, given the growing complexity of government (across, for instance, different agencies and levels of government), the decline of traditional and trusted media outlets covering government, and partisan polarization. To the extent that policymakers can break through these barriers, research suggests the need for policies to build on the trusted relationships that citizens hold with civic organizations, such as unions, churches, or community-based groups.

Conclusion

Our framework suggests a new way of thinking about the 2024 election results and its implications for Bidenomics battles over the future of progressive economic policy. Moreover, our arguments are relevant now, as policymakers consider whether to focus on a politics of “abundance” that focuses on removing constraints on new production, manufacturing, and innovation.57

Our framework suggests that the abundance approach could reduce the sense of competition over scarce goods and services—such as housing or health care—that can fuel right-wing populism. At the same time, we urge an important note of caution: Without adequate attention to how the gains of abundance are shared—and even more, how the gains of abundance are perceivedto be shared and with whom—how abundance policies build a sense of community, dignity, and identity, and the organizational underpinnings of abundance policies, an abundance approach that prioritizes production at all costs risks generating populist backlash.58

Broadly speaking, the urgent need for a new approach to economic policymaking is clear, as the U.S. democratic system—and other capitalist democracies around the world—face existential threats from rising right-wing populist movements. The framework proposed in this essay and the evidence from the broader essay series that will follow are not comprehensive; indeed, our hope is that this initiative can help spur further research, experimentation, and policy development in the months to come. Such work will be essential to building policies that not only deliver more inclusive and stable economic growth, but also reinforce the political foundations of democracy in a moment of democratic crisis.

About the authors

Alexander Hertel-Fernandez is associate professor and Vice Dean at the Columbia University School of International and Public Affairs and an Equitable Growth fellow. His research and teaching focuses on the intersection of politics and markets in the United States, especially the politics of policy design, labor, and government influence. He previously served in the Biden-Harris Administration in the U.S. Department of Labor and the Office of Management and Budget and is the author or co-editor of three books, most recently The American Political Economy (Cambridge, 2021).

Shayna Strom is the president and CEO of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. Previously, Strom served as the chief deputy national political director at the American Civil Liberties Union. She also has had a significant government career, including serving on the Biden-Harris transition team, working for 4 years in the Obama White House Office of Management and Budget, and serving as counsel on the Senate Judiciary Committee for Sen. Al Franken (D-MN). Strom has taught at Johns Hopkins University, Sarah Lawrence College, and the Biden Institute at the University of Delaware.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!

End Notes

1. We acknowledge that protecting democracy is not the only objective of what economic policy should encompass beyond focusing on technical outcomes (as Elizabeth Popp Berman has cogently argued). Economic policy should also consider broader questions of power and social structure.

2. For an important overview, see Cass Mudde, The Far Right Today (New York: Polity Press, 2019); see also “Cas Mudde – Populism in the Twenty-First Century: An Illiberal Democratic Response to Undemocratic Liberalism,” available at https://amc.sas.upenn.edu/cas-mudde-populism-twenty-first-century (last accessed April 2025).

3. Sheri Berman, “The Causes of Populism in the West,” Annual Review of Political Science 24 (2021): 71–88, available at https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102503.

4. Ibid.

5. Authoritarian Populism Index,” available at https://populismindex.com/ (last accessed April 2025).

6. Theda Skocpol and Vanessa Williamson, The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2016), available at https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-tea-party-and-the-remaking-of-republican-conservatism-9780190633660.

7. Christopher S. Parker and Matthew Barreto, Change They Can’t Believe In: The Tea Party and Reactionary Politics in America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013), available at https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691151830/change-they-cant-believe-in.

8. Theda Skocpol and Caroline Tervo, eds., Upending American Politics (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2020), available at https://global.oup.com/academic/product/upending-american-politics-9780190083533.

9. Bernie Becker, “Trump’s 6 populist positions,” Politico, February 13, 2016, available at https://www.politico.com/story/2016/02/donald-trump-working-class-voters-219231.

10. Nate Cohn, “Postmortems Are Bad at Predictions: Democrats May Just Need a ‘Change’ Election,” The New York Times, December 20, 2024, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/20/upshot/election-democrats-postmortem.html.

11. Sociologist Elizabeth Popp Berman has argued that this style of economic thinking considers policy problems as technical problems, not political ones, and, in the process, ignores power and social structures. See Elizabeth Popp Berman, Thinking like an Economist: How Efficiency Replace Equality in U.S. Public Policy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2022), available at https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691167381/thinking-like-an-economist

12. The New York Times, reporting on the 2025 annual conference of economists, recently ran an article covering this topic. See Ben Casselman, “Economists Are in the Wilderness. Can They Find a Way Back to Influence?,” The New York Times, January 10, 2025, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/10/business/economy/economists-politics-trump.html.

13. Jason Furman, Richard Cooper Lecture at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, Washington, DC, September 27, 2024, available at https://www.piie.com/sites/default/files/2024-09/furman2024-09-27.pdf.

14. We readily acknowledge that there are many other important interventions to address the threats that right-wing populism poses to democracy that ought to be debated, such as changes to the structure of U.S. political parties and our electoral system. We focus in this essay on the levers related to economic policy. Relatedly, we also acknowledge that the problem of right-wing populism is just as much a “demand” as a “supply” problem—and recognize the importance of political leaders in democratic backsliding, as Larry Bartels has argued. See Larry Bartels, Democracy Erodes from the Top: Leaders, Citizens, and the Challenge of Populism in Europe (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2023).

15. Karin Fischer, “Why Hungary Inspired Trump’s Vision for Higher Ed,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, January 15, 2025, available at https://www.chronicle.com/article/why-hungary-inspired-trumps-vision-for-higher-ed.

16. Hugh Bradley, “Jair Bolsonaro: Brazil’s Populist Threat” (Washington: Democratic Erosion Consortium, 2022), available at https://www.democratic-erosion.com/2022/04/28/jair-bolsonaro-brazils-populist-threat/.

17. Jordan Kyle and Limor Gultchin, “Populists in Power Around the World” (London: Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, 2018), available at https://institute.global/insights/geopolitics-and-security/populists-power-around-world.

18. Manuel Funke, Moritz Schularick, and Christoph Trebesch, “Populist Leaders and the Economy,” American Economic Review 113 (12) (2023): 3249–3288, available at https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20202045.

19. Yotam Margalit, “Economic Insecurity and the Causes of Populism, Reconsidered,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 33 (4) (2019): 152–170, available at https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.33.4.152.

20. Yotam Margalit, Shir Raviv, and Omer Solodoch, “The Cultural Origins of Populism,” The Journal of Politics 87 (2) (2025): 393–410, available at https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/epdf/10.1086/732985.

21. Thiemo Fetzer, “Did Austerity Cause Brexit?” American Economic Review 109 (11) (2019): 3249–3286, available at https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20181164.

22. Chase Foster and Jeffry Freiden, “Compensation, Austerity, and Populism: Social Spending and Voting in 17 Western European Countries” (2022), available at https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/jfrieden/files/fosterfrieden2022compensationpopulism5.3.pdf.

23. Leonardo Baccini, “Austerity, economic vulnerability, and populism,” American Journal of Political Science (2025), available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ajps.12865.

24. David Autor and others, “Importing Political Polarization? The Electoral Consequences of Rising Trade Exposure,” American Economic Review 110 (10) (2020): 3139–3183, available at https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20170011.

25. Jiwon Choi and others, “Local Economic and Political Effects of Trade Deals: Evidence from NAFTA,” American Economic Review 114 (6) (2024): 1540–1575, available at https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20220425; Autor and others, “Importing Political Polarization? The Electoral Consequences of Rising Trade Exposure.”

26. Melinda N. Ritchie and Hye Young You, “Trump and Trade: Protectionist Politics and Redistributive Policy,” The Journal of Politics 83 (2) (2021): 800–805, available at https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/710322?journalCode=jop.

27. Erik Voeten, “The Energy Transition and Support for the Radical Right: Evidence from the Netherlands,” Comparative Political Studies 58 (2) (2024), available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/00104140241237468

28. Margalit, Raviv, and Solodoch, “The Cultural Origins of Populism.”

29. Rafaela Dancygier and others, “Emigration and radical right populism,” American Journal of Political Science 69 (1) (2024): 252–267, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ajps.12852.

30. Katherine J. Cramer, The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2016), available at https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/P/bo22879533.html.

31. Tarik Abou-Chadi, Denis Cohen, and Thomas Kurer, “Rental Market Risk and Radical Right Support,” Comparative Political Studies (2024), available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00104140241306963.

32. Charlotte Cavaille and Jeremy Ferwerda, “How Distributional Conflict over In-Kind Benefits Generates Support for Far-Right Parties,” The Journal of Politics 85 (1) (2023): 19–33, available at https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/720643.

33. Ben Ansell and others, “Sheltering Populists? House Prices and Support for Populist Parties,” The Journal of Politics 84 (3) (2022), available at https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/718354.

34. Skocpol and Williamson, The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism.

35. Manuel Funke and Christoph Trebesch, “Financial Crises and the Populist Right” (Munich: ifo Institut, 2017), available at https://www.ifo.de/DocDL/dice-report-2017-4-funke-trebesch-december.pdf.

36. Noam Gidron and Peter A. Hall, “Populism as a Problem of Social Integration,” Comparative Political Studies 53 (7) (2019): 1027–1059, available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0010414019879947.

37. Ibid.

38. Tarik About-Chadi and Thomas Kurer, “Economic Risk within the Household and Voting for the Radical Right,” World Politics 73 (3) (2021): 482–511, available at https://muse.jhu.edu/article/798090.

39. Giuseppe Ciccolini, “Who is Left Behind? Economic Status Loss and Populist Radical Right Voting,” Perspectives on Politics (2025), available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/perspectives-on-politics/article/who-is-left-behind-economic-status-loss-and-populist-radical-right-voting/8DD23A6C5454488E7F41F7C5633B095F

40. Jeremy Ferwerda, Justin Gest, and Tyler Reny, “Nostalgic deprivation and populism: Evidence from 19 European countries,” European Journal of Political Research (2024), available at https://ejpr.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1475-6765.12738.

41. Michele Lamont, The Dignity of Working Men: Morality and the Boundaries of Race, Class, and Immigration (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002), available at https://www.hup.harvard.edu/books/9780674009929.

42. Dan Rodrik and Stefanie Stantcheva, “Fixing capitalism’s good jobs problem,” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 37 (4) (2021): 824–837, available at https://drodrik.scholar.harvard.edu/files/dani-rodrik/files/fixing_capitalisms_good_jobs_problem.pdf

43. Sung In Kim and Peter A. Hall, “Fairness and Support for Populist Parties,” Comparative Political Studies 57 (7) (2024): 1071–1106, available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/00104140231193013.

44. Gidron and Hall, “Populism as a Problem of Social Integration.”

45. John S. Ahlquist and Margaret Levi, In the Interest of Others: Organizations and Social Activism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013), available at https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691158563/in-the-interest-of-others.

46. Ari A. Ray and Jonas G. Pontusson, “Trade unions and the partisan preferences of their members: Sweden 1986–2021,” Socio-Economic Review 23 (1) (2025): 51–73, available at https://academic.oup.com/ser/article/23/1/51/7673115.

47. Nicholas Lemann, “Bidenomics Is Starting to Transform America. Why Has No One Noticed?,” The New Yorker, October 28, 2024, available at https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2024/11/04/bidenomics-is-starting-to-transform-america-why-has-no-one-noticed.

48. David Dayen, “The Case for Deliverism,” The American Prospect, October 12, 2021, available at https://prospect.org/politics/case-for-deliverism/. Deliverism is, in many ways, a thinner version of a concept that political scientists have written about for decades, known as “policy feedback loops.” See Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson, “Policy Feedback in an Age of Polarization,” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 685 (1) (2019): 8–28, available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0002716219871222.

49. Ian Prasad Philbrick, “Why Isn’t Biden’s Expanded Child Tax Credit More Popular?,” The New York Times, January 5, 2022, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/05/upshot/biden-child-tax-credit.html; Jamila Michener, “Policy Feedback in the Pandemic: Lessons from Three Key Policies” (Washington: Roosevelt Institute, 2023), available at https://rooseveltinstitute.org/publications/policy-feedback-in-the-pandemic/.

50. Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, “Beyond Deliverism,” Democracy Journal (Spring 2025), available at https://democracyjournal.org/magazine/76/beyond-deliverism/.

51. Mary Beth Maxwell, “Time for People-Centered Policy,” Democracy Journal (Spring 2025), available at https://democracyjournal.org/magazine/76/time-for-people-centered-policy/.

52. Ferwerda, Gest, and Reny, “Nostalgic deprivation and populism: Evidence from 19 European countries.”

53. Jacob Hacker and others, eds., The American Political Economy, “Introduction” (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2021), available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/american-political-economy/657C72D5D48808A67794B20AD7A611DA.

54. Ilyana Kuziemko, Nicolas Longuet-Marx, and Suresh Naidu, “‘Compensate the Losers?’ Economic Policy and Partisan Realignment in the US.” Working paper 31794 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2023), available at https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w31794/w31794.pdf.

55. Washington Center for Equitable Growth, “What is predistribution?” (2015), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/predistribution/.

56. Suzanne Mettler, The Submerged State (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011). See also Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, “How Policymakers Can Craft Measures That Endure and Build Political Power” (Washington: Roosevelt Institute, 2020), available at https://rooseveltinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/RI_How-Policymakers-Can-Craft-Measures-that-Endure-and-Build-Political-Power-Working-Paper-2020.pdf.

57. Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, Abundance (New York City: Simon & Schuster, 2025), available at https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/Abundance/Ezra-Klein/9781668023488.

58. Kate Andrias and Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, “Abundance that Works for Workers—and American Democracy,” Fireside Stacks, March 31, 2025, available at https://www.firesidestacks.com/p/abundance-that-works-for-workersand