Child care costs are going to rise, but policymakers can help U.S. families manage these increases

For decades, the U.S. child care market has been on the verge of a crisis. As any parent knows, child care in the United States has long been too expensive, hard to access, and of inconsistent quality. It hasn’t been working for families—but it also hasn’t been working for providers and their staff, who scrape by on razor-thin profit margins and some of the lowest wages in the U.S. economy. It is, as the U.S. Treasury Department concluded in September 2021, a failed market.

While many prominent economists have called for increased government investment in child care to correct this market failure, such investment has not materialized. Some policymakers express concerns that further government investment in the U.S. child care sector will exacerbate already-high inflation and child care costs, and indeed, in this current inflationary environment, higher child care costs are the last thing families need.

But it is exactly what they might get without sufficient public investment.

To recognize why, we must understand the current U.S. child care market and what it might be like in the future depending on the actions policymakers take now. This column first summarizes the supply crisis facing the industry and then previews three possible scenarios that could play out in the U.S. child care market with or without the necessary public support. All of the potential child care futures have one thing in common: rising costs. But only one path forward—the one built on public investments in the system—will best shield U.S. families from rising costs, control increasing child care prices, and build a more resilient child care sector.

The present: An impending child care supply crisis

One cause of the failing child care market is its primary source of funding. Unlike the publicly funded education system that kicks in when a child reaches Kindergarten or pre-K age, the child care system requires most parents to pay high out-of-pocket fees without any public or private system of borrowing to help cover the costs, unlike for higher education. Families incur these costs at a moment in their working lives when expenses are typically high and income is usually low.

This liquidity constraint puts a limit on how parents will tolerate increasing child care prices. When child care prices are too high, parents will seek other alternatives, which may include dropping out of the labor force to care for their children, even though this limits future income growth. Such constraints won’t stop prices from rising outright, as many parents will place a higher value on the time that child care provides them to engage in work than on the money spent on care. But it does prevent providers, many of whom genuinely care about the families they serve, from raising prices—and, in turn, their own and their employees’ wages—too quickly.

To keep prices from rising even higher when most families already struggle to afford child care, providers must keep their wages and those of their employees as low as possible. The average U.S. child care provider’s wage is just $13.22 an hour, or $27,490 per year for a full-time employee. These low wages may be keeping prices in check, but they are unsustainable and contribute to the inconsistent quality of care available to families.

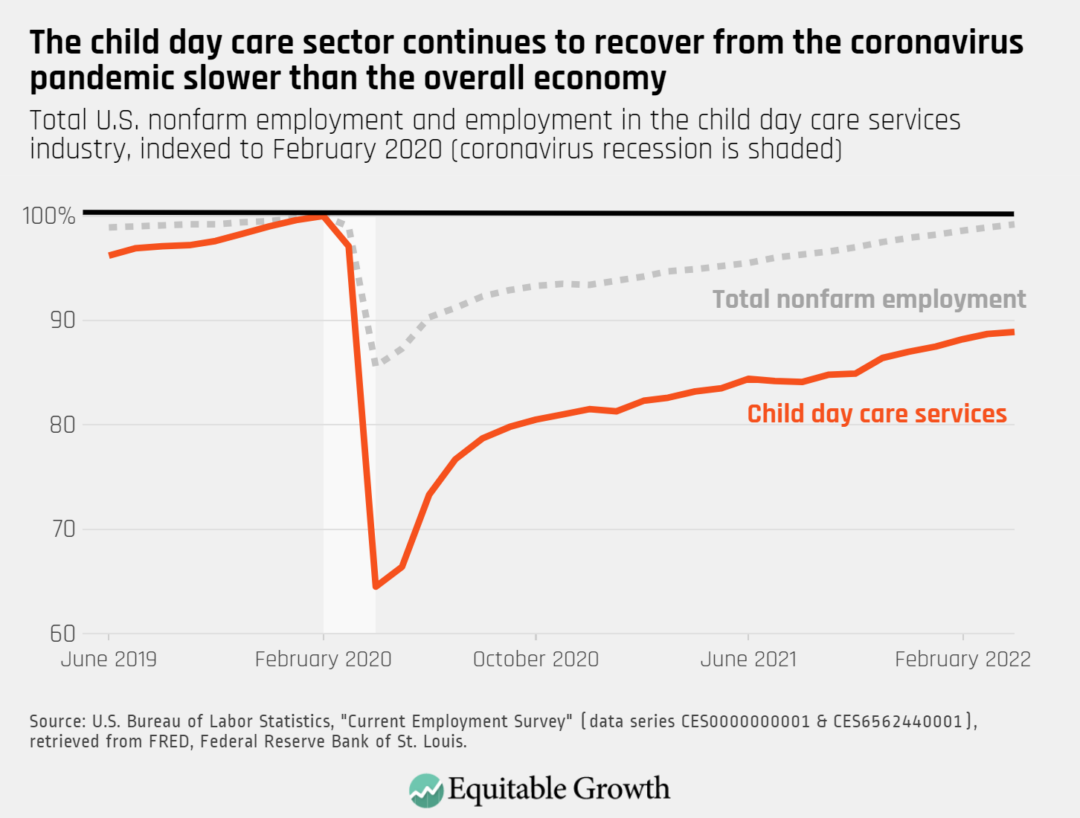

Low wages also are strangling the U.S. child care market. Many smaller home providers, where the owner may be the sole employee, have already been forced to close. And, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing recession, those providers that did not shutter their doors have struggled to hire new staff members. Employment in the child day care sector, for example, remains 116,000 jobs below its pre-pandemic level, and the sector added fewer than 3,000 jobs in April 2022, even as the broader labor market has recovered. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

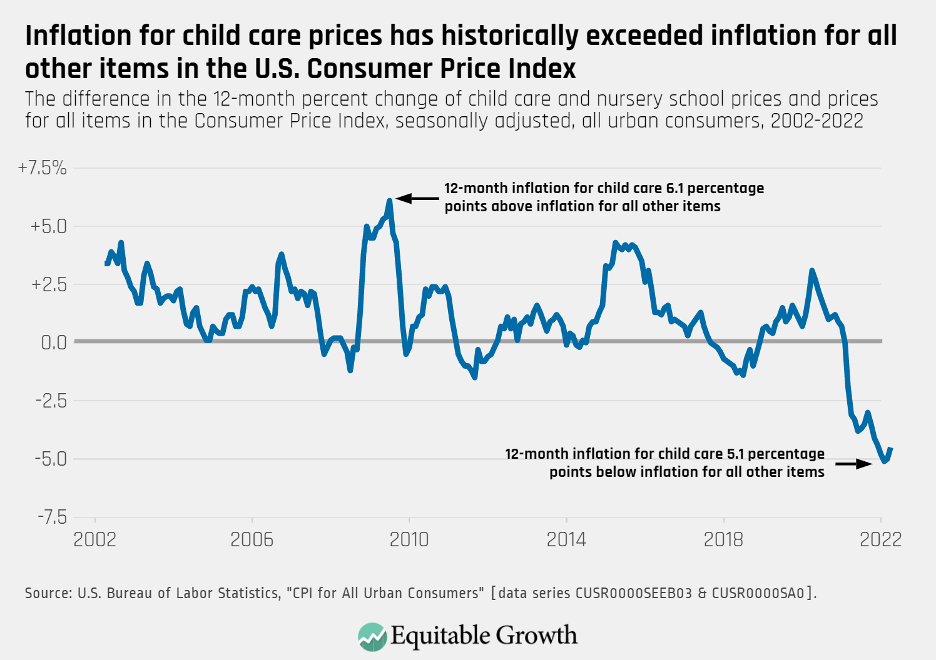

That child care prices are currently rising at a slower rate than the general Consumer Price Index should provide little comfort to policymakers and is not indicative of where child care prices are likely to go. Over the past two decades, child care prices have risen faster than the average for all other products, by approximately 1.1 percentage points. Once supply chain challenges ease and broader inflation cools, it is possible child care prices could once again rise faster than broader inflation, as they have in nearly 16 out of the past 20 years. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Long-term employment declines, coupled with a lethargic U.S. recovery from the pandemic in the child care sector, means that parents will have an even harder time finding safe, quality child care for their children. These supply challenges could spell an impending crisis for this already-struggling industry.

Currently, there are two potential futures for the U.S. child care market absent government investment. If wages stay low and the supply of child care stays constant or decreases, then parents will be left to fight for limited child care slots. This could force those parents who highly value child care—because it is a necessity for them to work—to pay higher prices. It may also drive other parents to exit the labor force entirely because they can’t find acceptable care or because rising prices have made paid work no longer sufficiently profitable.

Alternatively, child care employers could attract workers to enter the sector by offering higher wages and thus increasing the supply of care. These higher wages, however, would be passed on to families in the form of higher prices because most providers’ profit margins are already so low.

Either way, families in the United States would see higher prices that threaten their economic security. Evidence shows that higher prices compel parents to drop out of the labor force or reduce their work hours to focus on child rearing, which, in turn, dampens broader economic growth.

The potential first future: Providers leave wages low, yet costs for families still rise

The first possible future scenario for the U.S. child care market is a continuation of the status quo, in which parents’ liquidity constraints incentivize providers to keep prices—and, in turn, wages—as low as possible.

In this scenario, child care prices may not rise immediately, but providers would continue to struggle with hiring and retaining workers. With fewer workers to care for children and meet the child-to-staff ratios necessary to provide safe, quality care, providers will be required to reduce available child care slots.

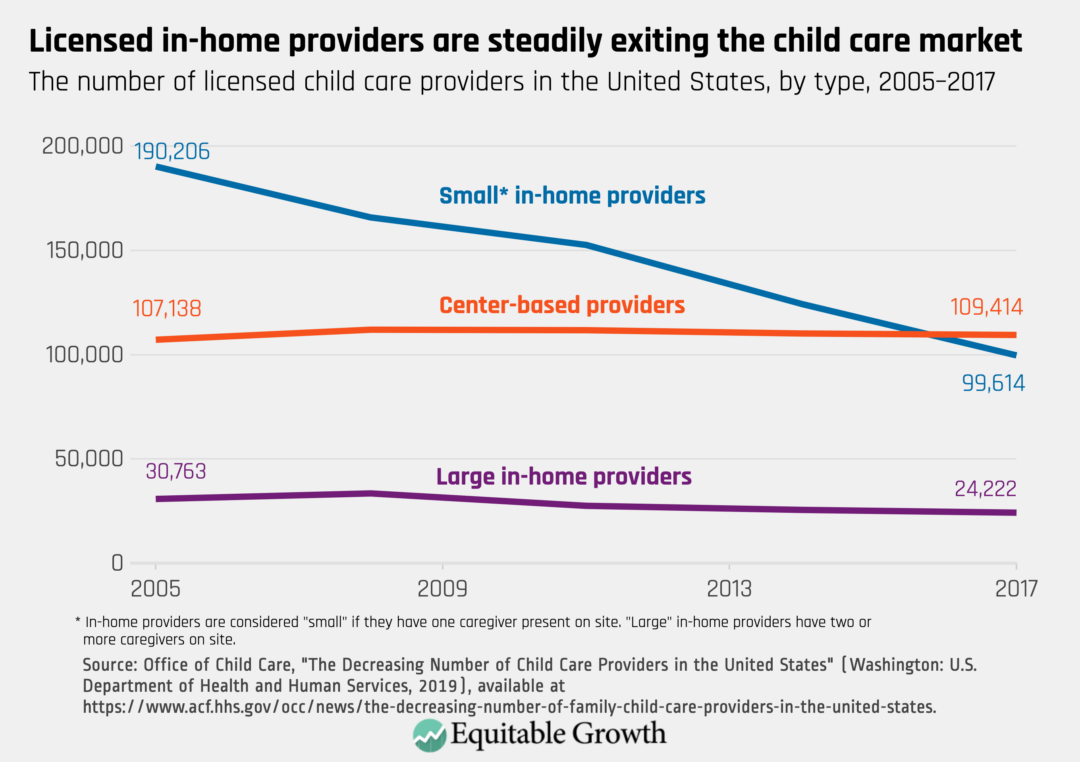

The number of licensed small in-home providers is already declining steadily, either because they are leaving the industry entirely or they are entering the unlicensed “underground” market, where subsidies aren’t available, and quality and safety standards cannot be enforced. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

There are several potential outcomes should the child care market follow this path forward. As the supply of care decreases, families will compete for fewer and fewer available slots, and competition for rare high-quality slots could be even worse. Over time, such competition may cause prices to rise.

If and how much prices increase depends on how willing parents are to tolerate them. Parents who strongly value high-quality care may be willing to pay a premium for a product in short supply. Many may begrudgingly accept higher prices up to a point because they are still better off paying for expensive child care than dropping out of the labor force. Because there is some elasticity in parents’ demand for child care, others will deem child care too expensive and drop out of the labor market to focus on child rearing.

If, however, parents’ liquidity constraints are powerful enough that prices cannot rise significantly despite a low-supply environment, then there will still not be enough child care slots to meet demand. Parents who cannot find care may be forced to stop working or reduce their hours regardless of their willingness to pay.

Essentially, in this future scenario, the costs of caring for their children increase among all U.S. families. For those that continue to purchase formal child care, those higher costs come in the form of child care prices. For those that stop buying care, it is the opportunity cost of forgone work.

The potential second future: Providers raise wages for workers—and prices for families

The second possible future scenario for the U.S. child care market is one in which providers respond to current labor market pressure and quickly raise wages to compete with other sectors to attract talent amid rising costs of living.

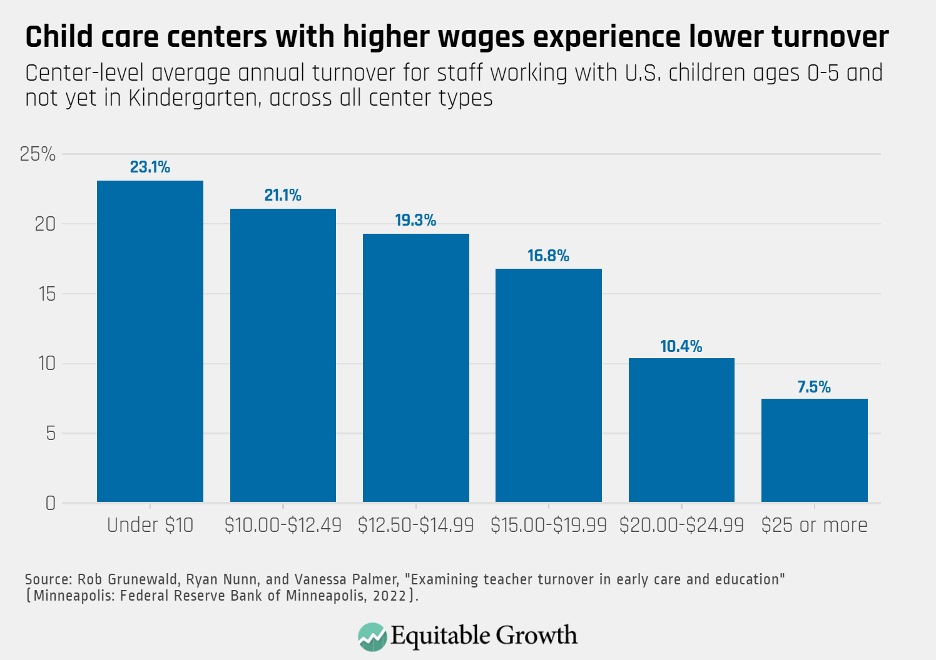

Such a move would not only bring child care workers back to the sector after the COVID-19 recession but also help keep workers in the jobs they already have. Recent research from the Minneapolis Federal Reserve finds that child care centers that pay $15 per hour or less lose approximately 1 in 5 staff members per year, while centers that pay $20 or more per hour have a turnover rate of 1 in 10 employees or fewer per year. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

Such an industrywide shift would expand the supply of child care across the country. Yet it also would inherently require providers to raise their prices. According to an analysis by the Center for American Progress, salaries and benefits account for 65 percent to 76 percent of providers’ costs. Without sufficient cash reserves, investments, or profits to cushion these rising costs, providers must pass them on to the families they serve.

How this increase in provider costs translates to the real costs that families pay varies by state earnings averages and regulations. In West Virginia, for example, raising the salaries of child care center workers to parity with Kindergarten teachers would result in a 24 percent to 27 percent increase in what families pay, according to the Center for American Progress’ Cost of Child Care Tool. Even closing the pay gap between child care workers and teachers by just half would result in a 12 percent to 13 percent price increase. While such an increase would represent a one-time bump in prices as wages are brought up to close this pay gap, it also would raise the “floor” from which all future prices will grow.

In this second future scenario, the supply of child care will stabilize, but families are set to be rocked by steeply increasing prices—absent government investment in the industry.

Fortunately, government investment opens the door to a third potential future. This potential third way forward would lead to a greater supply of child care, stable costs for families, and, ultimately, broad-based growth for the whole economy.

The third potential future: Government investment in child care expands supply and stabilizes costs for families

The third potential future for child care in the United States is one in which the federal government makes a sustained, robust investment in child care and early education for the first time. Recent policy proposals envision an expanded subsidy system on a sliding scale, in which most families pay between 0 percent and 7 percent of their household income, with subsidies picking up the leftover price.

For some families, child care costs would drop to $0, but even families required to pay the maximum 7 percent of their income would likely see a meaningful decrease in their child care costs under this system. On average, U.S. families currently spend approximately 10 percent of household income on child care. Continuing with figures from West Virginia, middle-class families’ child care spending in that state would fall by more than half, from an average of 10.4 percent of income to just 5 percent—a savings of more than $100 per week.

Such a system would also allow child care providers the breathing room they need to raise their workers’ wages. The new subsidy system would shield most families from ever paying more than 7 percent of their income on care. Even if the formal price that providers charge were to rise, public spending would eventually make up the difference. This has the added benefit of attracting new talent into the child care field, expanding the supply of child care, and easing upward pressure on prices due to insufficient supply to meet demand.

If, in keeping with smart policy design, a subsidized system is gradually phased in over a few years, then in the short term some families who are not yet eligible for subsidies may experience modest price increases due to increased demand for care from the expanded subsidies. In a phased-in plan, however, all eligible families will receive subsidies in a few years, and at that point, nearly all families will pay significantly less for child care.

Further, smart policy choices, such as using federal grant funds to cover the cost of increasing child care workers’ wages during the phase-in, can shield the families who are next in line for subsidies from experiencing cost increases arising from the higher wages.

Well-designed policy can also keep prices aligned with their fair market value. Theoretically, the expansion of the government’s role in the child care market could allow providers to raise prices higher than the market would otherwise dictate without losing many customers because most families will never pay more than 7 percent of their income on care and the government would make up the difference. But public investment does not mean a “blank check” from the government.

Recent proposals require states to submit payment rates and cost-estimation models to access federal child care money. Subsidy amounts are thus calculated on the anticipated real-world cost of providing quality care in local markets and not on potentially arbitrary prices set by the more egregious profit-motivated actors. Indeed, this is the only future in which the government’s regulatory authority and deliberative process for assessing costs as a buyer can help keep price increases in check.

Conclusion

Some policymakers point to the possibility that child care prices may still rise following government investment, as well as the impact on those families who are ineligible or not yet receiving subsidies, as reasons not to invest in child care. Such concerns miss an important counterfactual: Without such government investment, costs are going to rise for all families. This is the hard truth about the future of child care in the United States—and, if history proves instructive, prices are likely to rise faster than the rate of inflation in the long term.

The question for policymakers, therefore, is not whether child care costs will continue to go up—they will—but rather how policymakers can help the most families meet these rising costs while building a stronger, more stable child care industry. Helping families face the child care crisis will boost the U.S. economy in the short term by freeing up parents’ time and resources to enter the labor market and in the long term by supporting children’s educational and socio-emotional development, which will pay dividends for decades to come.

The future of child care remains uncertain, but one thing is not: Inaction in the face of the failed child care market will be too costly for families, and the economy, to bear.